“Testimony received by Institute Assistant Luba Melchior.” This sentence appears on 61 of the 512 complete witness testimonies collected from Polish survivors of Nazi persecution by the Polish Research Institute (PIZ) in Lund, Sweden, in 1945 and 1946.1 Yet, Polish Holocaust survivor Luba Melchior did not leave her own testimony with the PIZ survivor historical commission and documentation center. Nor, it seems, did she leave behind any deliberate personal account of her life and experiences before, during, or after the Second World War and the Holocaust.

As the only Jewish survivor of Nazi persecution employed as part of the primarily non-Jewish PIZ historical commission and documentation center, Luba Melchior was responsible not only for interviewing other survivors, but also for the Jewish “section” of the institute.2 In this capacity, she coordinated and met with Dr. Nella Rost at the World Jewish Congress’ Jewish Historical Commission in Stockholm and collaborated with the Conseil des Associations Juives de Belgique (Council of Jewish Associations of Belgium) in Brussels. Although her role at PIZ is well known, she exists in most published research as little more than a footnote.3

In these and other respects, Luba Melchior is not unlike Rachel Auerbach, Miriam Novitch, Eva Reichmann, and Nella Rost, whose contributions to documenting the history of the Holocaust have received scant scholarly attention until relatively recently. The neglect has been due to a variety of factors, including their gender, education, and the nature of their documentation work.

As scholars such as Laura Jockusch and Boaz Cohen have argued, organized Holocaust documentation efforts in the post-war period were dominated at the highest ranks by men, among them historians and other academics. Women were mainly conducting interviews, collecting material, and working as archivists and secretaries.4 In addition, most of the women involved in these efforts were neither professional historians nor even academics. This was true of Rachel Auerbach, Miriam Novitch, and Luba Melchior, and partly true of Nella Rost and Eva Reichmann, who had doctoral degrees but not in the discipline of history.

Historian Sharon Geva argues that the marginalization of Rachel Auberbach and Miriam Novitch can be attributed in part to the fact that their work of documenting, researching, and commemorating the Holocaust “reflected distinctly feminine attributes” and “their work as documenters took place behind the scenes.”5 For these and other reasons, the predominantly male leaders of the historical commissions have received most of the recognition as ‘survivor-historians’ of the Holocaust.

Fortunately, awareness of women’s crucial role in documenting the Holocaust has been slowly increasing thanks to recent research that sheds light on the work of Rachel Auerbach, Miriam Novitch, Eva Reichmann, and Nella Rost.6 This research breaks through a notion of Holocaust survivor-historians as primarily male academics and professional historians who led the Holocaust historical commissions and documentation centers. It does this by acknowledging that although these women (and, by extension, other women and men like them) may not have been professional historians or even academics, they were Holocaust survivor-historians because they dedicated themselves to the cause of documenting, collecting, preserving, and commemorating the experiences of others for the sake of history and justice. They also influenced and established methods and methodologies for interviewing, collecting, and archiving, and fought in various ways against bureaucracy, lack of funding, and public and academic disinterest to continue collecting, preserve existing collections, and so forth.

The result of their efforts are the collections of testimonies, documents, artifacts, and other material that historians and other researchers are still only beginning to analyze. As Sharon Geva suggests, the passing of the survivor generation has increased the understanding of how valuable this material is and, consequently, how important survivor-historians like Auerbach and Novitch are to knowledge of and scholarship on the Holocaust.7

This is a critical shift in thinking, researching, and writing about early Holocaust documentation efforts and the survivors who conducted this work. It drives home how little is known about the many women and men who can and should be recognized as Holocaust survivor-historians, and how gaining such missing knowledge can improve our understanding of both the Holocaust and early attempts to document Holocaust history.

In my research, Luba Melchior is one of these individuals.8 And while I believe the case should be made for all the survivors of the PIZ historical commission, I argue that recognizing and analyzing Luba Melchior as a survivor-historian, as has been done to different extents with Rachel Auerbach, Miriam Novitch, Eva Reichmann, and Nella Rost, helps to understand PIZ – a Polish (i.e., non-Jewish) historical commission with a ‘Jewish section’ – in the context of the overall phenomenon of Jewish survivor historical commissions. It also takes Luba Melchior out of the footnotes and into the analysis, making visible not only that but also how she contributed to documenting Holocaust history.

But, as this blog contribution demonstrates, on top of the reasons already given that have kept her and others in the margins, an additional impediment to making my argument is a dearth of empirical materials. Rachel Auerbach, Miriam Novitch, Eva Reichmann, and Nella Rost made their contributions to documenting Holocaust history in notable positions over long periods of time and left behind extensive empirical materials for researchers.9 By contrast, Luba Melchior conducted her most notable and ostensibly well-documented work in the historically more obscure context of Sweden during the course of just over a year and left behind a less extensive collection of testimonies and empirical legacy than her four contemporaries. While there are hints of further contributions she made to documenting Holocaust history, the details are elusive. The challenge I face in my research is finding and piecing together whatever material does exist to make empirically-sound arguments about Luba Melchior’s role and significance in relation to PIZ and Holocaust history.

Here, I share where I currently stand in this ongoing methodological journey. What follows represents a first attempt at coalescing the documents and other material I have gathered to-date into a cohesive but incomplete narrative of Luba Melchior’s life and experiences as a Holocaust survivor and a Holocaust survivor-historian. It is a work in progress, and my hope is that by openly sharing this journey with others in this area of research, more documents about Luba Melchior may be identified that can help write her history.

***

While Luba Melchior may have chosen not to record her own testimony, she had no choice but to submit to repeated official questioning by Swedish authorities after she arrived in Malmö, Sweden as a ‘repatriate’ on April 28, 1945. The official government paper trail this produced consists largely of police reports, residence permits, travel passes (required for movement within Sweden), visa applications, and employment documents.10 The data contained in these documents is dry and repetitive, and filled with sometimes difficult to interpret shorthand and a host of dead ends, but nonetheless offers important clues about Luba and her life and experiences. Linking these clues to other archival traces and sources enables me to add dimension to the bare facts.

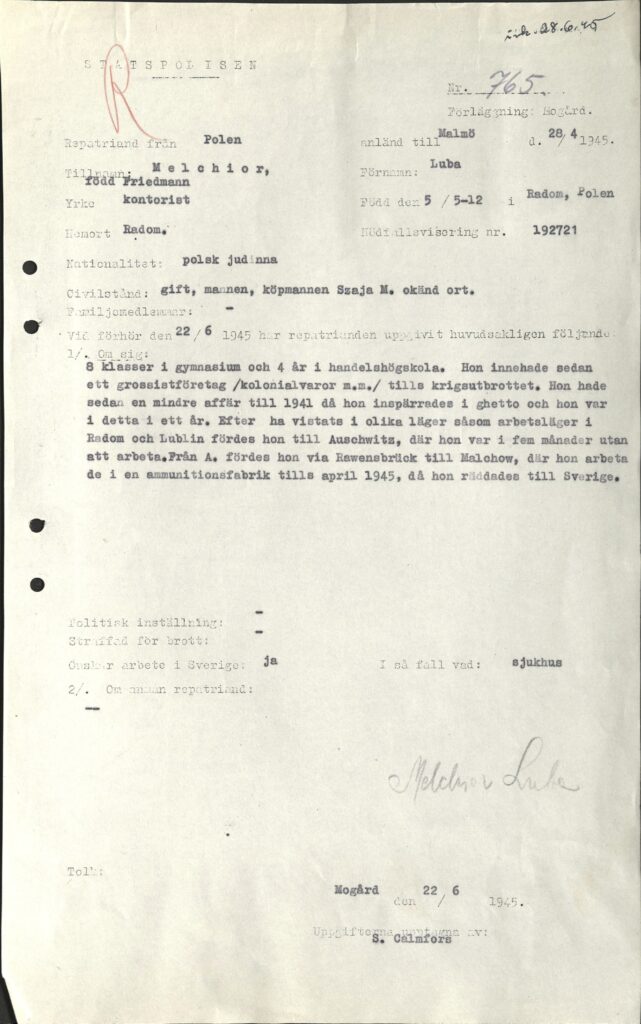

A police report dated June 22, 1945, for example, reads like a short CV. “Name: Luba Melchior, born Friedman. Born: May 5, 1912, in Radom, Poland. Profession: Clerk. Nationality: Polish Jew.” A paragraph of text describes her education and subsequent employment, with the latter easily flowing into a summary of her imprisonment in ghettos, concentration camps, and forced labor camps as if these were merely a continuation of her employment record. The paragraph notes, for instance, that she was “without work for five months” while imprisoned in Auschwitz. More poignantly, this document reveals that Melchior appears to have been unaware at that time that her husband had been murdered in Auschwitz. “Marital status: married, husband, merchant Szaja M. unknown place.”11

As perfunctory as this document is, when it and other documents are read alongside additional material, a picture begins to emerge of Luba Melchior’s life and losses, her imprisonment under the Nazis, and her role as a survivor-historian. To start with, between the Swedish archival documents and the Pages of Testimony on five of her murdered family members that she left with Yad Vashem in 1992, it is possible to form a basic account of her life before and during the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Luba Melchior was born in Radom on May 5, 1912, to parents Moshe-Yankel Frydman, a merchant, and Chawa Frydman, née Zuker or Tzuker, a housewife. She appears to have had older siblings as well as a younger brother, David, who was born in 1916. After completing gymnasium in Radom in 1929, she attended business school in Warsaw for four years, graduating in 1933.12 At some point during her studies, she married Yeshayahu Melchior (Szaja) who was born in Radom in 1901, and gave birth to their son, Efraim, in 1932.

The young family settled in Radom where, according to Luba’s statements to the Swedish authorities, she owned a wholesale groceries business until the outbreak of the Second World War. This may have been a family business, either with her husband and/or with her father. According to the police report, after the start of the war, she had a “small business until 1941, when she was imprisoned in the ghetto.”13 This rupture occurred in early April 1941, when two ghettos – the ‘large’ with around 25,000 Jewish inhabitants, and the ‘small’ with around 8,000 – were established in Radom.14 Luba and her family lived in close proximity to her parents and brother David in the large ghetto: her parents and brother at 50 Traugutta Street, and Luba, Yeshayahu (Szaja), and Efraim at 55 Traugutta Street.15

In August 1942, both of the ghettos in Radom were liquidated – the small ghetto on August 5 and the large ghetto between August 16-18 – and all but a few thousand Jews were transported to Treblinka for extermination.16 On August 17, 1942, Luba’s mother Chawa was murdered during the liquidation of the large ghetto.17 During the liquidation, Luba witnessed the murder of her cousin Jack Werber’s first wife and three-year-old daughter.18 Following the liquidations, the Jews who remained in Radom worked in forced labor camps in and around Radom. Along with Luba, Moshe-Yankel, Yeshayahu, Efraim, and David all appear to have survived the liquidation, but she was the only one who survived the Holocaust.

At Yad Layeled, the children’s museum at the Ghetto Fighters’ House in Israel, a plaque commemorating Efraim Melchior can be seen on the long wall of names of Jewish children murdered during the Holocaust. It was donated by Luba Melchior.19 This plaque shows that Efraim died in Auschwitz in 1944. Moshe-Yankel and Yeshayahu also died in Auschwitz, according to the documents submitted by Luba to Yad Vashem, though when is not indicated. The date and place of David’s murder are not specified in the document Luba submitted to Yad Vashem; however, other documents indicate clues to his fate, such as that he had been imprisoned in Mauthausen.

The details of Luba’s journey from the Radom ghetto to liberation are not recorded, but she did indicate to the Swedish authorities that she had been in forced labor camps in Radom and Lublin (Majdanek and/or its subcamps), as well as in the concentration camps Majdanek, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Ravensbrück, and Malchow. She was almost certainly not in Lublin/Majdanek before the November 3, 1943 “Erntefest” massacre, when all of the approximately 45,000 Jewish prisoners of Majdanek and other Lublin labor camps and prisons were murdered. Her transfer from Majdanek to Auschwitz would likely have taken place no later than spring 1944, when the prisoners of the camp were evacuated due to the advance of Soviet troops.20 As noted earlier, the Swedish police report indicates that she was “without work” in Auschwitz for five months, so this may point to the length of time she spent there. A transport list in the Arolsen archives shows she was transferred from Auschwitz to Ravensbrück on November 3, 1944. Returning again to the Swedish police report, it can be inferred that her time in the main camp of Ravensbrück was also brief. The report states: “From [Auschwitz] she was taken via Ravensbrück to Malchow [a subcamp of Ravensbrück], where she worked in an ammunition factory until April 1945, when she was rescued to Sweden.”21

Almost immediately following her arrival to Sweden as a repatriate/refugee on April 28, 1945, Luba Melchior became part of the PIZ initiative to gather evidence and testimony from other Polish survivors of Nazi persecution. First, she was part of the ad-hoc documentation commissions established by Dr. Zygmunt Łakociński in several quarantine camps in southern Sweden.22 Subsequently, on November 22, 1945, she was formally employed under a Swedish government plan to employ educated refugees as “archive workers.”23 Of the nine survivor employees of PIZ, only Luba was Jewish. The other survivors and the co-founder of PIZ, Zygmunt Łakociński, were all non-Jewish Poles. Consequently, Luba was placed in charge of the Jewish ‘section’ of PIZ. As I have shown elsewhere, however, Luba’s engagement with “Jewish matters”24 did not mean that she was responsible only for Jewish survivors’ testimonies, or that the non-Jewish survivors were responsible only for non-Jewish survivors’ testimonies. Rather, there was what I have called Jewish / non-Jewish ‘crossover’ in 43 of the 512 complete testimonies in the PIZ collection. Of the 61 complete witness testimonies Luba was responsible for, 22 were given by non-Jewish Poles.25

Part of Luba’s responsibility involved coordination with Jewish organizations. During her time at PIZ, she corresponded and met with Dr. Nella Rost, who was head of the World Jewish Congress’ Jewish Historical Commission in Stockholm. Dr. Rost had previously worked as vice-director of the Krakow branch of the Central Jewish Historical Commission in Poland.26 Correspondence between Luba Melchior, Nella Rost, and Zygmunt Łakociński in the PIZ archive shows that there was an exchange of information between the two institutions, including regarding methodologies and testimonies.27 Unfortunately, I have found no account of what took place during their personal meeting, which occurred in November 1946.28 Perhaps Luba gave her testimony to Nella Rost? If she did, its whereabouts are as unclear as many of the other testimonies gathered by the Jewish Historical Commission in Stockholm.

As historian Johannes Heuman has shown, after Nella Rost’s departure in 1951, the Stockholm commission ceased to exist and its archive was dispersed, with parts of it presumed lost or destroyed. In her continued capacity with the World Jewish Congress, Rost had taken some of the commissions’ documents with her when she left Sweden.29 Among these were several testimonies that had originated with PIZ, including at least five that Luba Melchior had been responsible for. These were among those Nella Rost sent to Joseph Wulf in the 1970s, which is why they are now part of the Joseph Wulf papers at the Central Archives for Research on the History of the Jews in Germany (Zentralarchiv zur Erforschung der Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland). But, again, there is no evidence of her own testimony in this archive.

In August 1946, Luba took a temporary leave of absence from PIZ to travel to Brussels, Belgium. She had been invited by the Council of Jewish Associations of Belgium (Conseil des Associations Juives de Belgique) in Brussels to attend a conference and conduct what Zygmunt Łakociński characterized as ‘several assignments of great importance.’30 I have yet to discover any documentation about who extended the invitation, what conference she was attending, or any other specifics about the time she spent in Belgium. I believe, however, that the invitation was connected with Abusz Werber, Luba’s cousin on her father’s side of the family; a point I will return to momentarily. While in Belgium, she interviewed at least one Polish survivor, whose testimony, dated September 4, 1946, was added to the PIZ collection.31 By the end of September 1946, Luba had returned to Sweden and her work at PIZ. After her return, it appears she was considering traveling or may have traveled to Belgium again in early October for an unspecified purpose.32

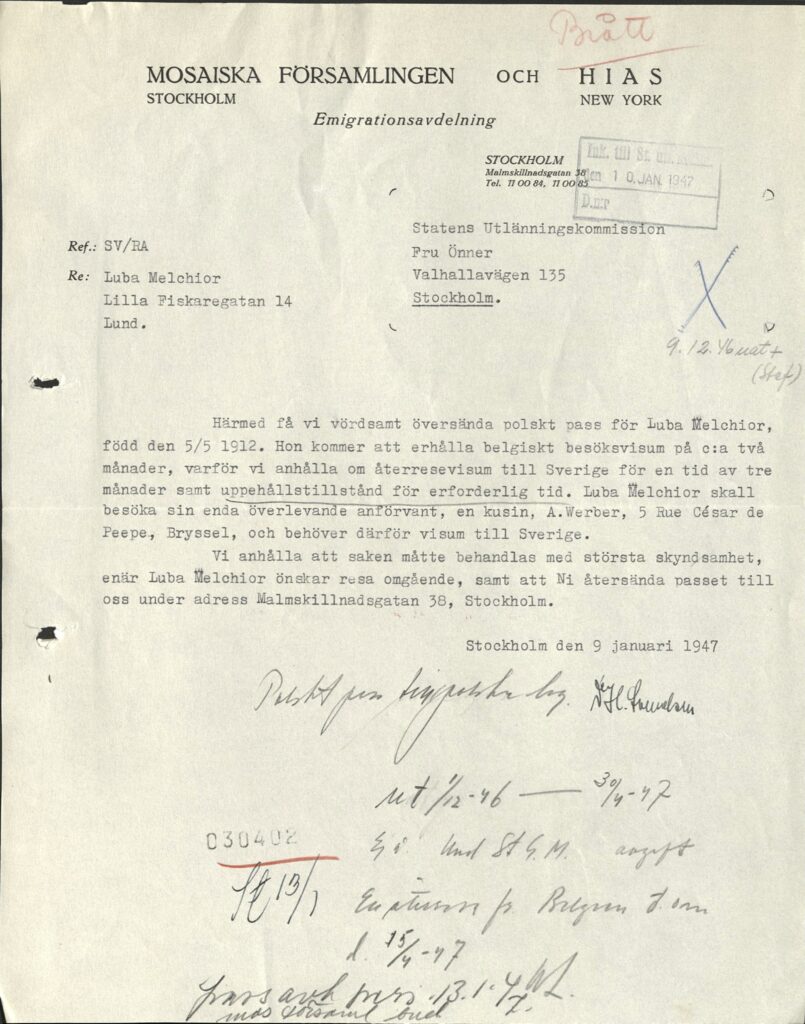

On December 1, 1946, government funding for PIZ ended, leaving Luba in search of new employment. Her time in Belgium must have been fruitful, however, as there is evidence that Beatrice Vulcan33 of the Joint Distribution Committee in Belgium was considering Luba for an unspecified position in a children’s home in Belgium.34 She again applied to the Swedish authorities for a visa to travel to Belgium. One of the last documents in her official Swedish government case file refers to this application, indicating that this time she planned “to visit her only surviving relative, a cousin, A. Werber, [of] 5 Rue César de Peepe [sic]” for around two months 35. Apparently, she requested a return visa to Sweden, though she did not use it. This is where her official Swedish government case file ends.

In a letter Luba wrote to Zygmunt Łakociński from Brussels on January 21, 1947, she apologizes to him for leaving behind some “problems” and “baggage” that he had handled financially on her behalf and for which she was reimbursing him. This may indicate that her ultimate decision not to return to Sweden was made after she left the country. Perhaps employment had materialized after her arrival? The letter is friendly and she passes on “warm greetings from cousins,” presumably Abusz Werber and his family.36 At the time, she was probably living with Abusz, his wife Shifra, and son Michel, in their rented house on Rue César de Paepe, as she had indicated in her Swedish visa request.37 I believe that her previous trip(s) to Belgium and her decision to remain there rather than return to Sweden were connected to the Werbers, not only personally but also in connection with her Holocaust documentation work and related activism.

Abusz Werber had moved from Radom to Belgium in 1929 and had survived there during the Second World War under a false identity while actively engaging in underground resistance activities. Following the war, he continued his activism with a variety of organizations, including the Council of Jewish Associations of Belgium, which was connected with the World Jewish Congress.38 In the immediate post-war period, Abusz and Shifra Werber’s public involvement in a variety of cultural and political activities meant that their home on Rue César de Paepe was frequented by political and cultural figures from Belgium, Eretz Israel, and elsewhere, and this activity was also organized around a regular salon. In addition, Abusz had a small shoe factory on the lower floors of the house. Abusz’s son Michel recalls that Abusz was “helped by a female cousin, Luba, a survivor of Auschwitz,” though, frustratingly, he does not elaborate on what aspect of his work or in what capacity she helped him.39

Like other survivors in the immediate post-war period, Luba had spent time while in Sweden searching for loved ones. Correspondence in the JDC Archives Text Collection, for instance, shows that she was able to locate her niece, Jadwiga Teitelbaum, and was working with the JDC to bring her to Sweden; plans that were derailed due to Luba’s move to Belgium.40 She had likely located Abusz Werber more directly given his high profile. It is also possible that the contact was facilitated through Nella Rost, since both the Jewish Historical Commission in Stockholm and the Council of Jewish Associations of Belgium were both associated with the World Jewish Congress.

Luba and Abusz probably began corresponding in spring 1946, since in early March she reported to the Swedish authorities that she was considering moving to the United States, where she had relatives; but in late June, she stated that she was considering moving to either the U.S. or to Belgium.41 It was also in late June 1946 that she applied for the visa to travel to Belgium for her collaboration with the Council of Jewish Associations of Belgium.42 The Belgian Council’s invitation and her contact with her well-connected cousin who was associated with that organization thus coincide and, I believe, are directly connected. Supporting this argument, the invitation involved attending a conference, and Michel Werber writes that “one of Abusz’s main activities was organizing conferences.”43 The US Holocaust Memorial Museum likewise notes that, “In 1945-46 Abusz initiated and participated in many conferences in Brussels and other European cities where he reported on the deeds of heroic Jewish resistance in Belgium.” In the near future, I hope to visit the A. Werber archive at Yad Vashem, which might yield further clues as to Luba Melchior’s involvement with the Council of Jewish Associations of Belgium and/or other post-war organizations he was associated with.

From the sparse post-war correspondence involving Luba Melchior in the PIZ archive, it is known that she also continued her efforts in relation to PIZ and the survivor testimonies as she was making new contacts in the Werber home and elsewhere. In her January 1947 letter to Zygmunt Łakociński, she writes:

I meet different people here and try to tell as much as I can about the Institute [PIZ]. I can’t be completely sure but there are great chances to form a group in Germany in Munich in a children’s camp (actually a big boarding school). I met a woman who will be responsible for it. She became interested in our cause. Unfortunately, I didn’t have any documents with me [referring to PIZ testimonies] but promised to send them later to her to Paris. […] Thankful for [you] sending these and some first pages of others for I have here promised.44

This letter provides insight into how Luba Melchior viewed herself and her documentation work during and after her time at PIZ. Although she was no longer employed with PIZ, she continued to identify with the institute and perpetuate its work (which she refers to as “our cause”). She was also communicating with others about Holocaust documentation efforts more generally and seeking new ways of continuing her own documentation work. Her vague mention of the “group” at a children’s camp in Munich offers a tantalizing clue about her subsequent Holocaust documentation work and activism that I have yet to glean any solid insight into.

In early 1948, she mentions in a letter to her former PIZ colleague Krystyna Karier that she had been very busy due to a recent stay in Germany, though she does not indicate what the purpose of the visit had been.45 Could this have been related to the “group” in Munich? I have considered the possibility that perhaps this initiative was connected to the Aschau children’s DP camp, which was located outside of Munich, but it seems unlikely.46 I have also considered that perhaps it was related in some way to Beatrice Vulcan at the JDC in Belgium and the children’s home that Luba was being considered for there. One possibility is that Luba Melchior engaged in documentation and/or other work with child survivors. At this time, I have more questions and possibilities than answers regarding this issue.

Like other survivors who documented the Holocaust, Luba Melchior was motivated in her collection and documentation work by a sense of moral responsibility; a motivation that did not waver after she left PIZ. In her 1948 letter to Krystyna Karier, she declared: “The work for the Institute is our duty to present and future generations. We suffered and we understand and can orient the material.”47 While this leaves little doubt regarding her continued commitment to Holocaust documentation, it begs the question: why she did not appear to record her own testimony? Did she perhaps believe that her moral obligation was fulfilled by documenting others’ experiences? Maybe she felt as Miriam Novitch did, that her own story was “irrelevant”?48 Of course, there is a chance that she did write about her experiences and I just have not found this material.

With her 1947 and 1948 letters in the PIZ archive, another Swedish paper trail comes to an end. In general, too, the documentation (at least what I have found so far) is scarce from here, with just a few traces giving hints to the remainder of Luba Melchior’s long life. On August 26, 1960, she became, under the name Luba Frydman, a naturalized citizen of Belgium.49 Her request for naturalization noted that she was stateless, a widow, and had resided in Belgium since February 18, 194750, 1960: 36.], a slightly later date than her earliest extant letter to Zygmunt Łakociński indicates. By the 1970s, she was living in Israel, according to another Werber cousin, Martin, the son of Jack Werber (whose first wife and young daughter Luba had witnessed being murdered in the liquidation of the Radom ghetto in 1942).51

Luba Frydman Melchior died on May 12, 2000, age 88. She is buried in the Kiryat Shaul Cemetery in Tel Aviv, Israel. Her gravestone is indicative of the documentation of her life, at least as I have found it. The upright stone reads: “Luba Melchior. Radom, Poland. Deceased 7th of Iyar 5760 [May 12, 2000]. 1912-2000.” The flat stone reads in part: “In memory of my beloved who perished in the Holocaust […] May God revenge their blood” and names her parents, husband, son, and brother David.52

In death, as in life, Holocaust survivor-historian Luba Melchior gave priority to the memory and experiences of others, ostensibly leaving her own history to be pieced together by future historians like me.

My sincere thanks to Malin Thor Tureby for helping me to improve this text with her insightful feedback, to Roman Wroblewski and Mordechay Giloh for their valuable help with translations, and to Christine Schmidt for inspiring me to contribute to the EHRI Document Blog in the first place.

Archives, institutions or collections this blog post refers to:

The Polish Research Institute in Lund (PIZ) archive (including the Witnessing Genocide portal), Lund University Library (Lunds Universitet); Statens utlänningskommission (Sweden’s State Aliens Commission), The National Archives of Sweden (Riksarkivet); Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names; JDC Archives; Arolsen Archives; Ghetto Fighters’ House, Israel; U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; Zentralarchiv zur Erforschung der Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland (Central Archives for Research on the History of the Jews in Germany).

Suggested documents and information:

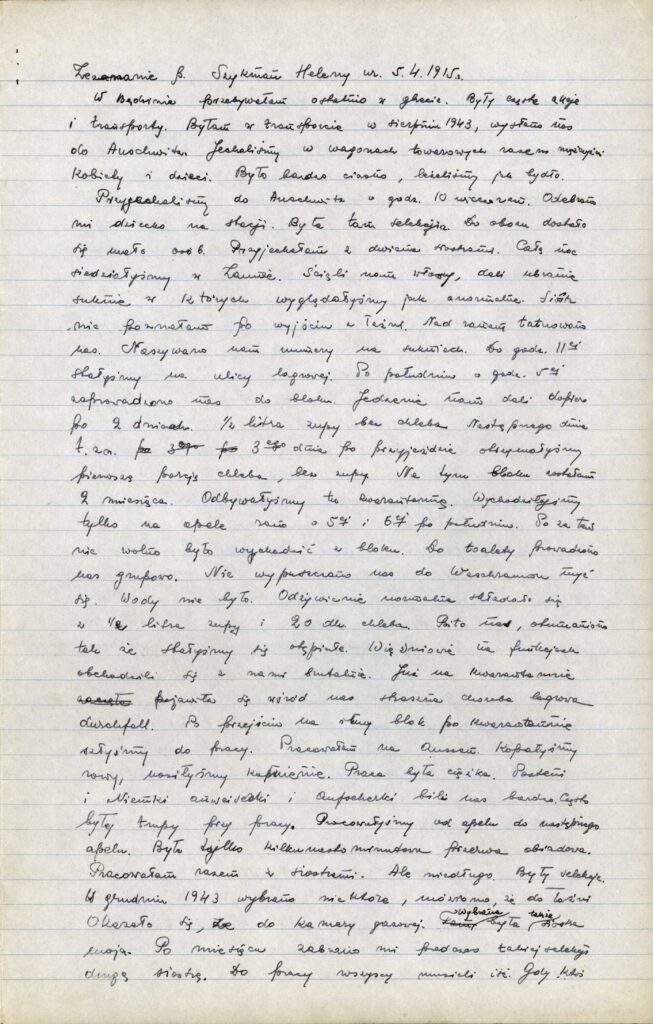

PIZ Record of Witness Testimony 491, given by a Jewish survivor to Luba Melchior, transcribed and translated from Polish to English. Source: The Witnessing Genocide portal, Lund University Library, Lund, Sweden. Link to document – http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:alvin:portal:record-103876

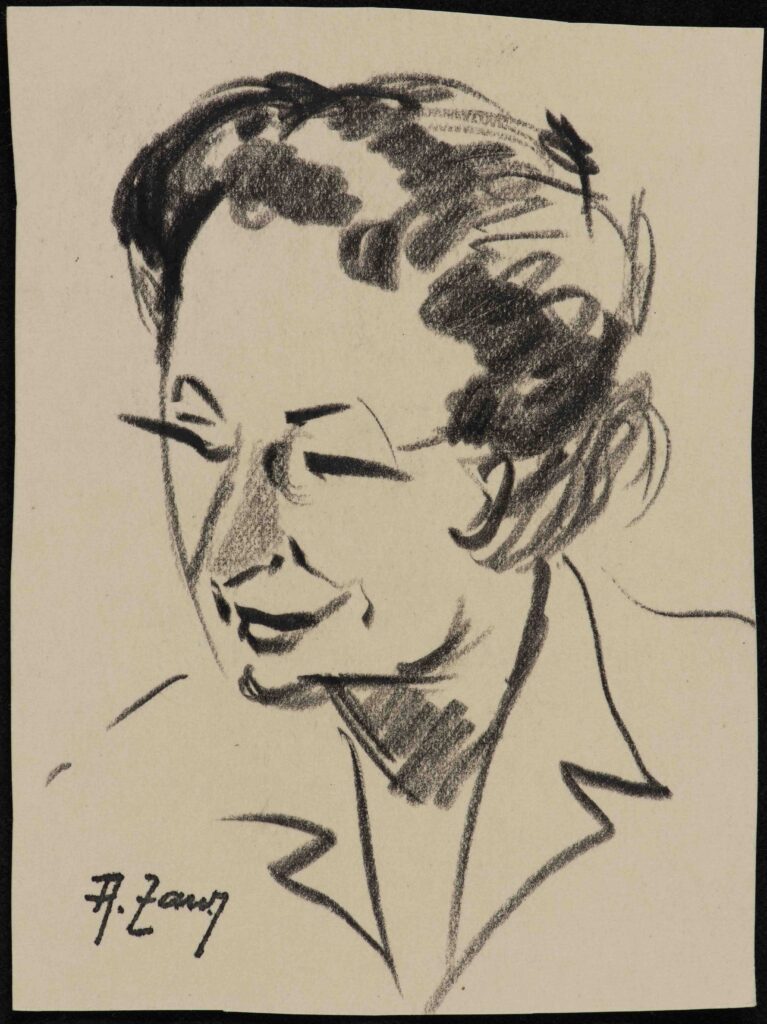

Drawing of Luba Melchior, 1946, signed by A. Zawadzki. Public domain image. In the collection of the Polish Research Institute (PIZ) in Lund, Lund University Library. Link to source: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:alvin:portal:record-111446

Statspolisen Nr. 765. Police report dated June 28, 1945, now in the Swedish government case file of Luba Melchior. Source: Riksarkivet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Moshe-Yankel Frydman’s Page of Testimony, submitted to Yad Vashem by Luba Melchior in 1992. Source: The Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names, Yad Vashem.org. Link to source: https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=en&itemId=2015347&ind=1

The plaque dedicated to Efraim Melchior at Yad Layeled, which was donated by Luba Melchior. Image credit: Victoria Van Orden Martínez, photographed July 12, 2022.

Group photo of members of the PIZ historical commission and documentation center, circa 1946. Luba Melchior is located bottom row center. Photographer unknown. Public domain image. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PIZ_1946_Foto.jpg

Mosaiska Församlingen och HIAS [Jewish Community and Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society], letter to Luba Melchior dated January 9, 1947, now in the Swedish government case file of Luba Melchior, Source: Riksarkivet, Stockholm, Sweden.

- All complete testimonies may be found here; the testimonies Luba Melchior was responsible for can be found here. ↩

- June 10, 1946, letter to the Historical Commission in Munich, signed by Zygmunt Łakociński, p.1., Vol. 46:8, The Polish Research Institute in Lund (PIZ) archive, Lund University Library, Sweden. ↩

- Historian Izabela Dahl has written about Luba Melchior in, for instance: Izabela A. Dahl, “Witnessing the Holocaust: Jewish Experiences and the Collection of the Polish Source Institute in Lund,” in Early Holocaust Memory in Sweden: Archives, Testimonies and Reflections, ed. Johannes Heuman and Pontus Rudberg (Basingstoke & New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 77-78. Historian Malin Thor Tureby has argued for the importance of understanding the similarities between the different historical commissions that were organized around Europe and the Polish Research Institute (PIZ) in Sweden, as well as for the need for further research on the collaboration and connections between the Jewish Historical Commission in Stockholm and PIZ and on the roles of Nella Rost and Luba Melchior in the Swedish context. See: Malin Thor Tureby, “Memories, testimonies and oral history: On collections and research about and with Holocaust survivors in Sweden”, Swedish Government Official Reports, SOU 2020:2, Holocaust Remembrance and Representation. Documentation from a Research Conference (Stockholm: Norstedts juridik, 2020), 67-92. ↩

- Laura Jockusch, Collect and Record! Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 186. See also: Boaz Cohen, “Rachel Auerbach, Yad Vashem, and Israeli Holocaust Memory,” in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 20: Making Holocaust Memory, ed. Gabriel N. Finder, Natalia Aleksiun, and Antony Polonsky (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007), 220. ↩

- Sharon Geva, “Documenters, Researchers and Commemorators: The Life Stories and Work of Miriam Novitch and Rachel Auerbach in Comparative Perspective,” MORESHET Journal for the Study of the Holocaust and Antisemitism 16 (2019), 80. ↩

- In addition to the already cited works by Laura Jockusch, Boaz Cohen, and Sharon Geva, see also, for example: Johannes Heuman, “In Search of Documentation: Nella Rost and the Jewish Historical Commission,” in Early Holocaust Memory in Sweden: Archives, Testimonies and Reflections, ed. Johannes Heuman and Pontus Rudberg, The Holocaust and Its Contexts (Palgrave MacMillan, 2021); Christine Schmidt. ““We Are All Witnesses”: Eva Reichmann and the Wiener Library’s Eyewitness Accounts Collection.” In Agency and the Holocaust: Essays in Honor of Debórah Dwork, edited by Thomas Kühne and Mary Jane Rein, 123-140. (Springer International Publishing, 2020); Karolina Szymaniak, “On the Ice Floe: Rachel Auerbach – the Life of a Yiddishist Intellectual in Early Twentieth Century Poland,” in Catastrophe and Utopia: Jewish Intellectuals in Central and Eastern Europe in the 1930s and 1940s, ed. Joachim von Puttkamer and Ferenc Laczo (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2017). ↩

- Geva, 83. ↩

- Luba Melchior is one of the survivors of Nazi persecution who came to Sweden as refugees that I am writing about in my doctoral dissertation, tentatively titled, Afterlives: Histories of Survivors of Nazi Persecution in Sweden. ↩

- In Nella Rost’s case, however, many of the testimonies she gathered were scattered, destroyed, or are presumed lost. See: Heuman, “In Search of Documentation: Nella Rost and the Jewish Historical Commission.” ↩

- F 1 AC:14117 Melchior, Luba. Statens utlänningskommission Kanslibyrån (SUK), Riksarkivet, Stockholm. ↩

- “Statspolisen (Swedish state police) Nr. 765,” SUK. Translated from Swedish by author. All translations are by author unless noted otherwise. ↩

- “Statens arbetsmarknadskommission: Deklaration för arkivarbete (Luba Melchior),” 46.3 a, PIZ. ↩

- Statspolisen, SUK. ↩

- Polin: Virtual Shetl, “Ghetto in Radom.” https://sztetl.org.pl/en/towns/r/601-radom/116-sites-of-martyrdom/49970-ghetto-radom. Accessed July 19, 2022. ↩

- Yad Vashem testimonies on the five family members submitted by Luba Melchior (see links in text). My thanks to Mordechay Giloh for checking the Hebrew content of the original documents alongside the automatic English translation provided by Yad Vashem and providing additional details. ↩

- Polin: Virtual Shetl, “Ghetto in Radom.” ↩

- Yad Vashem testimony on Chawa Melchior submitted by Luba Melchior (see link in text). ↩

- Jack Werber and Martin Werber (Afterward), Saving Children: Diary of a Buchenwald Survivor and Rescuer (New Brunswick and London: Routledge, 2014), 140. ↩

- I have inquired with the archivists at Ghetto Fighters’ House about when the plaque was donated and any other circumstances and am awaiting a response. ↩

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp: Conditions.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/lublin-majdanek-concentration-camp-conditions. Accessed 18 July 2022. ↩

- Statspolisen, SUK. ↩

- “Memoriał w sprawie polskiego instytutu źródłowego w Lund /Szwecka/” (Memorandum on the Polish source institute in Lund, Sweden), May 17, 1945, 44.1 c, PIZ; “Pracownice ‘komisyj dokumentacyjnych’” (Female workers of ‘documentation commissions’), PIZ 44.1 f; Dahl, 72; Eugeniusz Stanisław Kruszewski, Polski Instytut Żródłowy w Lund (1939-1972): Zarys Historii i Dorobek (Polish Source Institute in Lund (1939-1972): An outline of history and achievements) Londyn; Kopenhaga: Polski Uniwersytet na Obczyźnie; Instytut Polsko-Skandynawski, 2001), 25-26. ↩

- 44.5 g, PIZ; Dahl, 72. ↩

- “Program pracy. Polskiego Instytutu Źródłowego w Lund,” (undated notes in Polish on the history of PIZ), 44:5 g, PIZ. ↩

- Victoria Van Orden Martínez, “Witnessing against a Divide? An Analysis of Early Holocaust Testimonies Constructed in Interviews between Jewish and Non-Jewish Poles,” Holocaust Studies (2021, advance online publication) 1-23, https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2021.1981627. ↩

- Jockusch, 5. ↩

- Letters between Luba Melchior and/or Zygmunt Łakociński and Nella Rost dated between May 16 and November 16, 1946, 46.8, PIZ. ↩

- Letter to Nella Rost from Luba Melchior dated November 13, 1946, 46.8, PIZ. ↩

- See: Heuman, 55. ↩

- Paraphrased from a certificate written (in Swedish) by Zygmunt Lakociński regarding Luba Melchior, dated August 3, 1946, 44.2 i, PIZ. ↩

- Record of Witness Testimony 492, datelined Brussels, September 4, 1946, attributable to Luba Melchior. See: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:alvin:portal:record-103889. ↩

- A letter from Luba Melchior to Nella Rost datelined Lund, September 28, 1946, indicates she had returned from Belgium (46.8, PIZ). Regarding the possible subsequent trip, the details in her official case file are a bit vague, but it appears she applied for permission for another trip to Belgium with a departure date of October 5, 1946, but it is not immediately clear if she made that journey (notes made to visa application dated June 26, 1946, SUK). If she did, she was back in Lund on October 21, 1946, when she wrote to Nella Rost and remarked that she had been away (she does not indicate where she had been) so had not received Rost’s latest letter, which was dated October 1, 1946 (46.8, PIZ). ↩

- Another woman who appears often in the footnotes of Holocaust-related research but whose role in the JDC does not appear to have yet been analyzed by scholars. ↩

- “Letter to Frau Luba Melchior Friedman,” December 14, 1946, Records of the American Joint Distribution Committee: Stockholm office, 1941-1967, Subject Matter: Various – ST 41-67 / 3 / 4, JDC Archives. ↩

- Letter dated January 9, 1947, from Mosaiska församlingen och HIAS to Statens Utlänningskommission, SUK. ↩

- Three letters written by Luba Melchior and in 1947 and 1948, two to Zygmunt Łakociński and one to Krystyna Karier, Vol. 49, PIZ. My thanks to Roman Wroblewski for translating these letters, which were handwritten in Polish. ↩

- On the Werber family’s house in Brussels, see: Michel Werber, The Word of Abusz Werber: Bravery & Resistance During the Holocaust, (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), Location 2715. ↩

- Ibid., Location 352 and 2824. ↩

- Ibid., Location 2715. ↩

- See, for instance: “Letter from Luba Melchior to Miss Rabbinowitz,” November 23, 1946, ST 41-67 / 3 / 4 / ST. 170, JDC; “Letter from William Bein to American Joint Distribution Committee, Re: Jadwiga Teitelbaum (Child),” March 20, 1947, Records of the American Joint Distribution Committee: Warsaw office, 1945-1949, Record Group: Secretariat, Series: Correspondence: Organizations and Governments, W 45-49 / 1 / 4 / 92, JDC. ↩

- Two applications for residence permits, one dated March 11, 1946, the other dated June 26, 1946, SUK. ↩

- Visa application dated June 26, 1946, SUK. ↩

- Werber, The Word of Abusz Werber, Location 2842. ↩

- Vol. 49, PIZ. Translation from Polish by Roman Wroblewski. ↩

- Letter to Krystyna Karier from Luba, dated either February or March 27, 1948, Vol. 49, PIZ. ↩

- See, for example: Boaz Cohen and Rita Horváth, “Young witnesses in the DP camps: Children’s Holocaust testimony in context,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 11 (1; 2012):103-125, https://doi.org/10.1080/14725886.2012.646704. ↩

- Letter written by Luba Melchior to Krystyna Karier, dated February 27, 1948, Vol. 49, PIZ. Translated by Roman Wroblewski. ↩

- Sharon Geva, 83. ↩

- “Naturalisations – Naturalisatics,” Moniteur Belge — Belgisch Staatsblad (Belgian Official Gazette) 9 (1961): 136. ↩

- “Commission Des Naturalisations — Commissie Voor de Naturalisaties,” (Brussels, Belgium: Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers [Belgian Chamber of Representatives ↩

- Werber and Werber, Saving Children, 140. ↩

- Translated from Hebrew by Mordechay Giloh. ↩

Maureen Gafford

Congratulations on a complete study of the private life of Luba Melchior! You have made a difference!

Stefania

Such a good work!!! Very important and accurate.