On the morning of the 8th January 1959, Dr Joseph Thon passed away in the French Hospital, New York aged fifty-five with no spouse or children after a short illness.1 Born Joseph Teitelbaum in December 1903 in Żurawno, Poland (now Zhuravne in western Ukraine) Thon in his final years headed the tourist department for the Zionist Organization of America, although in his earlier life, Thon gained a reputation as an excellent author, economist and lecturer. Thon had been the vice-president of the General Zionist Organization of Poland, was a member of the administrative committee of the World Zionist Organization and the World Jewish Congress, as well as the representative of the Polish Jewish Refugee Fund in Geneva which he took over from Theodor Grubner in 1940. Thon was at the centre of Zionist politics in Poland and a key actor in the bureaucratic interplay in Geneva. Indeed, Raya Cohen has noted that since correspondence to and from Geneva was possible, many individuals such as Thon became ‘the central points of contact between the two halves of the divided Jewish world’.2

From the end of 1939 through to 1941, Thon corresponded with Polish citizens forced to flee their country, often attempting to place them at ease. A prominent Zionist and industrialist, Thon was director of the Polsko-Palestyńskiej Izby Handlowej (Polish-Palestinian Chamber of Commerce) and it is through these connections with industrial-economic activity in Poland and the Zionist cause, that many reached out to him when he relocated to Geneva.

This blog post contextualises the correspondence between Thon and five individuals who fled to England in 1939/40: Maksymilian Friede, Teodor Lewite, Celina Sokolow, Zofia Zelcer and Mieczysław Zagajski. From this small microhistory of letters, all held in one folder of the Abraham Silberschein deposit at Yad Vashem (YVA M.20/241) we can perhaps better place disconnected families within a network of communication centring around Geneva. These sources indicate that their authors attempted to draw on their personal acquaintance with Joseph Thon to obtain information regarding their families and friends remaining in occupied Poland. They referred to both professional and political as well as emotional ties they had with Thon in order to learn something about the fate of their loved ones.

Please follow the link for the EHRI collection description:

This text will run chronologically, first contextualising the five individuals and their life pre-1939, before going on to discuss some of their experiences of invasion. After this, a selection of letters from M.20/241 will be used to demonstrate instances of Thon’s associates attempting to use his newfound position to aid their families after they had fled Poland. The M.20/241 deposit contains letters from countries across the globe where Poles fled after September 1939. Here, we will discuss those from Britain. For translating these texts from Polish to English I would like to thank Alicja Gorska and Mirella Lewington who without this would not have been possible. Many letters remain unread in the archive from those who fled to different countries, but behind them lies the potential for further interpretation. May this post serve as an invitation to other scholars to build upon this rich and interesting deposit.

The Interwar Years: Thon’s correspondents in Warsaw

Maksymilian Friede (1887-1969)

During his time at the Chamber of Commerce, Thon worked with numerous industrialists and Zionists on a variety of projects, such as the production of the regular journal Palestyna i Bliski Wschód looking at industrial issues in the Middle East.3 In the Chamber, Thon worked with Judge Maksymilian Friede and his brother-in-law Artur Anker. Born in Warsaw in 1887, Friede was an economist and lawyer as well as a member of various economic and Zionist bodies in Poland.4 He was director of the Warsaw Stock Exchange from 1923 and sat on the Executive Council for the Minister of finance from 1932-39.5

Teodor Lewite (1919-?)

Friede’s senior at the Chamber of Commerce was Leon Lewite (1878-1944), the President of the Zionist Organisation of Poland and a former student, alongside Yitsḥak Grünbaum, of the writer Nahum Sokolow (1859-1936). Lewite, a strong promoter of aliyah to Palestine, sat on the right wing of the movement called General Zionists and was the leader of one of its factions: Et Livnot (“This is the Time to Build”); another faction – Al ha-Mishmar, was led by Grünbaum. Lewite married Dr. Salomea Kryńska, the head of the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO) in Poland, and together they had a son Teodor in 1919.

Celina Sokolow (1886-1984)

Whilst president of the World Zionist Organisation, Nahum Sokolow’s secretary was his daughter Celina (1886-1984), pictured here with her father in 1922; Celina was also a prominent member of WIZO, alongside her sister-in-law Helena and Helena’s sister, Salomea (for details of the familial relationships between the Sokolows and the Lewite’s see Fig.2). Teodor’s aunt, Dr Helena Sokolow nee Kryńska (1884-1982) married the engineer Henryk Sokolow (1883-1929) in 1910 and together they lived in Berlin until Henryk’s untimely death from influenza in 1929.6 Helena, a writer and art historian, eventually moved to St. Moritz in Engadine, Switzerland where she would befriend the painter Giovanni Giacometti.7 After her father’s death in 1936, Celina continued to engage in Zionist activities and increased her activity within WIZO.

Zofia Zelcer (1917-2000)

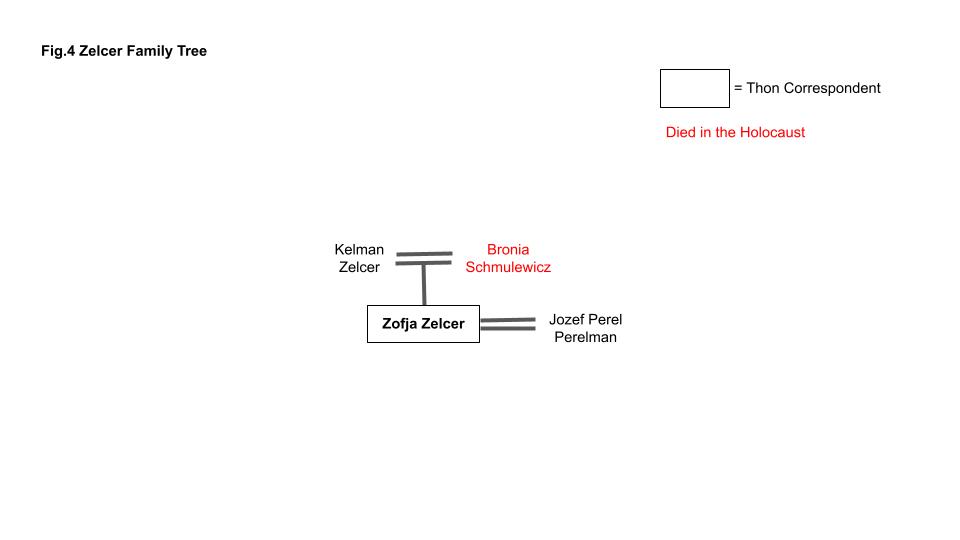

Although both the Lewite and Sokolow families’ main concern was emigration to Palestine and the spread of Zionism globally, it flourished locally in Warsaw with Moyshe Zonshayn describing Nalewki Street, a major centre of Jewish commerce, as the heart of the Jewish national “Kingdom”.8 At Nalewki 23, ‘K. Zelcer and D. Eber’, ran a textile manufacturing warehouse and were affiliates of the Chamber of Commerce – this was the business of the family of Zofia Zelcer. Zofia was born in 1917 to Kelman (Karol) Zelcer (1886-?) and Bronia (Braune) Scmulewicz (1889-1943). Unfortunately there is currently little else we know of her early life in Poland.

Mieczysław Zagajski (1885/93-1967)

Much more however is known about the philanthropic Zagajski family in Kielce – Mieczysław Zagajski (1885/93-1967) was the son of Herszel (d.1937) and Etla (1861-1942) and was one of at least six children (see Fig.3). Mieczysław’s grandfather Abraham purchased two limestone quarries in 1885 and as a result, the Wietrzna Calcium Factory became one of the richest businesses in Kielce allowing Herszel to build an orphanage, old people’s home and chapel amongst other altruistic projects. The Mieczysław Zagajski Department Store was founded in the 1920s with its main base in Warsaw, selling building supplies and representing the majority of Polish industrial firms abroad.9 In her memoirs of the period, a friend of the family Jadwiga Maurer remembered them as ‘millionaire’s on a global scale’ indeed – Mieczysław had his own plane.10 Mieczysław’s nephew, Abraham Wilner noted that his uncle was the only member of the family not to live in Kielce – preferring to conduct business from the capital.11

The Invasion of Poland

After the signing of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, German forces began the violent invasion of Poland on 1st September 1939 with many Polish Jews expecting the worst as atrocities began to be commonplace.12 As they recognised the situation deteriorating, Thon and Leon Lewite began to push for emigration within their colleagues, indeed Leon’s son Teodor had already left for England. In her memoir published in 2006, Roma Nutkiewicz Ben-Atar describes the situation when her mother, Guta, an employee of the Chamber of Commerce, was begged to leave Warsaw for Palestine by Lewite:

Levite had obtained four immigration certificates for us – not a small feat given the British policy severely restricting Jewish immigration. The atmosphere at home was very tense. My parents whispered to one another and to my grandparents. Then the verdict was announced. Since we could not take my grandparents along, and we could not leave them alone in Warsaw […] we were all staying together […]13

Alongside his wife Dr Salomea Lewite and his friend Maksymilian Friede, Leon became one of the founding members of the ‘Social Committee for State Defense Affairs at the Jewish Community in Warsaw’ in September 1939. The committee called for unity amongst Jewish organisations in Warsaw:

In the face of a turning point for the entire country, the representatives of Jewry in Warsaw declare that the Jewish population of the capital is ready for the most far-reaching sacrifice of blood and property to defend the Freedom and Independence of the Brightest Republic.14

Unlike Thon and Lewite, some had the fortune to be out of the country when the invasion occurred. In September 1939, Mieczysław Zagajski was in Geneva and never returned to Poland leaving behind his family and colossal art collection. Jadwiga Maurer recalled the moment of debate at the Zagajski manor bunker when the Wehrmacht were arriving – Mieczysław’s brother-in-law Eliasz Wilner firmly believed the Polish army would procure victory although many around were sceptical. The decision was made for the men to leave and the women to remain with Eliasz, a decision the Jadwiga Maurer believed did not make the most of their position and wealth.15 Eliasz’s son Abraham suggested that many in the family thought the invading Nazis would not harm women and children and thus those men of working age were most in danger.16 The remaining Jewish population in Kielce pondered the possibility of emigration to places such as Brazil, Shanghai and Chile with only a few hundred having moved to Palestine in the interwar years.17 Although immigration of any sort was difficult.

Refuge in England and Contact with Thon

Maksymilian Friede

After leaving Warsaw for Lvov and then Vilnius, Friede and his wife Stefania arrived in London in January 1940, moving into the Court Royal Hotel, and immediately wrote to their friend in Geneva asking after Artur Anker who remained in Poland. Friede asked what threats Artur faced and about Warsaw more generally before suggesting that Thon should contact Leon Cicurel in Paris for funds to support Artur’s emigration as: ‘sending money from here comes with many difficulties due to the foreign exchange regulations’.18 Leon Abraham Cicurel (1880-1973), a member of the famous Cicurel family, was an exporter of cotton through ‘Cicurel and Barda’ primarily based in Alexandria, Egypt but with large shares in the Lodz textile hub – Widzewska Manufaktura.19 The site, created by leading Jewish industrialist Oskar Kon in 1909, hosted numerous businesses until it faced bankruptcy in 1938 and was eventually subsumed into Herman Goering’s portfolio on the invasion of Poland.20 Widzewska Manufaktura, with its links to the Chamber of Commerce, is the most likely explanation as to how Cicurel knew Maksymilian Friede and Artur Anker.21

By the beginning of February 1940, Friede wrote again, asking Thon to contact Cicurel in Paris for Artur’s supplies but also began to lament his own situation, writing:

I am cut off from my home and closest family and I do not know how they are! I didn’t even want to write them when in Lwow and subsequently Wilno as I feared my correspondence would harm them.22

Friede wrote about his concern for his family, anxiety that evidently spurred him into action as he began appealing to Polish Government-in-exile ministers for visas for Artur and his wife Roma, but to no avail.23 He instead continued to appeal to Thon for information regarding Warsaw and Cicurel, with the latter eventually coming through and transferring Thon the £75 needed to get Artur out.24 Friede’s correspondence also contains references to his concern for his niece Irena Abramowicz (c.1906-1942) a philosopher, and her husband Ludwig (1897-1942) a doctor, who were residing in Kovel (Western Ukraine) at the time. Thon acted as a middle-man for Friede and Cicurel, and ensured Artur Anker made it safely out of Poland, the same however cannot be said for Friede’s niece and her husband, who were deported to Treblinka in 1942.25 Friede, his wife and son all left Britain in April 1941 for Halifax, Nova Scotia – eventually moving to New York City in June 1942.26

Teodor Lewite

Thon’s correspondence with Teodor Lewite after the fall of Poland, served to not only help Teodor, but also procure information for some of Thon’s other correspondents. Before he left Britain, Maksymilian Friede asked Thon for information regarding his friend and colleague Leon Lewite as he was ‘receiv[ing] conflicting news about him’.27 Lewite was at the top of the list of those wanted by the Nazis on the invasion and thus Leon and his wife Salomea went into hiding in an apartment on Szucha Avenue and were later smuggled out by Guta Nutkiewicz, fleeing to Trieste where they met Artur Anker, and boarded a ship for Haifa.28 In a letter from Teodor Lewite to Thon, Leon’s son confirmed his father had fled Warsaw under the changed name ‘Lewicki’ as ‘the former chairman of the Anti-Hitler committee in Poland cannot use his real name’.29 This information was then passed on to Friede, with Thon once again having acted as a connecting point for the forcibly divided colleagues.

In subsequent letters to Thon, Teodor Lewite requested his father’s friend’s help in ‘personal matters’ and stated that only because of Thon’s friendship and attitude to his family, specifically his aunt, Dr Helena Sokolow, is he asking such favours.30 Teodor used his connection to Thon in Geneva in an attempt to convince his aunt that she should flee St. Moritz and come to England or France, and although Helena did spend some time in Palestine with the Lewites she soon returned to the Engadine.31 Teodor used heavily emotional language, calling Helena ‘the dearest person I have got in this world except my mother’, in an attempt to get Thon to help, before reassuring him that any costs incurred will be repaid in due course.32 Through Thon, Teodor wrote to his aunt in January 1940:

Every time I am thinking of you I am wishing you were here with me. I regret the moment you left, but believe me that I am with you in my thoughts day and night.33

The relationship between Thon and Teodor Lewite was one of mutual assistance, with Teodor providing information to Thon on Leon Lewite, and Thon acting as a conduit for Teodor’s communication with his beloved Aunt. Teodor himself left England for Bombay, India, a few months later in July 1940 eventually settling in Israel with his parents.34

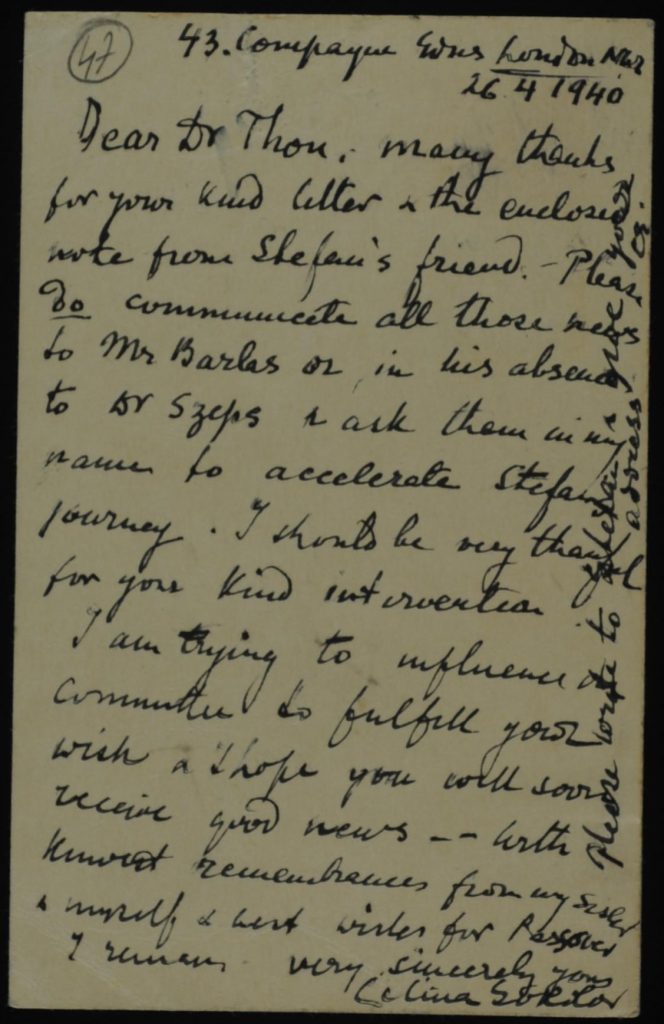

Celina Sokolow

Through her connections to her family and friends, alongside her reputation as a leading figure in the Women’s Zionist movement, Celina Sokolow and her address were listed in the Sonderfahndungsliste G.B., more commonly known as Hitler’s ‘Black Book’, a list of ‘dangerous’ individuals who would be sought by the SS Einsatzgruppen on the planned invasion of Britain.35 Celina asked for Thon’s intervention in ‘accelerat[ing] Stefan’s journey’ in return for ‘influenc[ing] our committee to fulfill your wish’.36 Stefan Sokolow (1923-99) was the son of Celina’s brother Leon (1889-1959) and his wife Stefania (1892-1969) and had been at school in England until the summer of 1939 when he went to visit his mother in Warsaw.37 Stefan was subsequently trapped in the Warsaw ghetto until 1942 when he was deported to Treblinka. Miraculously, Stefan jumped off of the train and made his way back to Warsaw then Vienna where he worked under false documents until 1944. After being recaptured he escaped again and made it to American troops in Czechoslovakia. Presumed dead, he turned up in Paris in May 1945.38 Celina believed Thon could have intervened in saving Stefan and often paired her request with a notion that she was doing something for him.

Zofia Zelcer

Thon was however not the only one who wished to help with Celina Sokolow’s request. Although it is unclear how they knew each other, Zofia Zelcer wrote to Thon in May 1940 stating:

As a result of Mrs Celina’s request, I would like my father to help Stefan. Would you like to add my letter to him? I am kindly asking you to send Mrs Samborska [Stefan’s mother, Stefania] to my father who lives where he used to be.39

Perhaps Stefania Samborska (Sokolow) was saved through these means as she survived the war – eventually relocating to Brazil. Alongside offering to help Thon help the Sokolows, Zofia wrote emotionally to Thon discussing Poland’s fate stating she was very pleased to ‘learn that you are one more person who escaped the “hell”’ but that she lives ‘as if in a dream […] I can’t even worry anymore, I don’t have the strength’.40 Her parents, Kelman and Bronia, are the main focus of her worries and she pleads with Thon to help them as much as he can:

Despite lazing around, I could not bring myself to write. You cannot imagine how difficult it is for me to focus on even the lightest read. I can sit for hours doing nothing. This never used to happen to me. I heard from one lady who is currently in Riga that my parents are well and that they are in Warsaw. I am happy they are alive but with word of what is happening in Warsaw and the lives of those who are there I do not rest but constantly worry about what is happening to my parents.41

It is unknown what happened to Zofia’s father Kelman but her mother Bronia was transferred to Poniatowa Concentration Camp where she was murdered in November 1943 as part of Aktion Erntefest.42

Mieczysław Zagajski

Just as Celina Sokolow requested Thon’s help in return for a favour to him, this quid pro quo arrangement was similarly present in Mieczysław Zagajski’s correspondence with Thon. Zagajski noted that Toedor Grubner, whom he had been corresponding with prior to Grubner’s replacement by Thon ‘frequently sent parcels for me, and I should be indeed glad if you would do the same’. Earlier in the letter Zagajski noted that on hearing Thon’s wish to work in Geneva and replace Grubner he had ‘passed an opinion in [his] favour’, reminding Thon of his debt.43 Zagajski requested Thon write to his mother Etla and his sister Cyrla Wilner ‘at least twice a week’ with Thon positively replying:

‘You may be rest assured, that I will do my best to come in touch with your family. I have already [written] four times to them during the last two weeks. I have also sent them three parcels containing chocolate’.44

Despite Thon’s efforts Etla and Cyrla never escaped Warsaw and were shot in the ghetto and deported to Treblinka respectively along with many members of their family (see Fig.3)45

Conclusion

Teodor Lewite, Maksymilian Friede, Celina Sokolow, Mieczyslw Zagajski and Zofja Zelcer were all linked to Joseph Thon in a variety of ways – some known and some not. Without more research into the specific connections and relationships that joined them, it is difficult to fully unpack the nature of the correspondence post-1939. What can be said with confidence however is that they all emerge from the specific context of Varsovian industrial Zionism where all were concerned with Aliyah to Palestine and all believed that increasing industry was the root to this. When Warsaw was invaded, Thon’s contacts were forced to flee around the world with this group heading to England – if only for a short period. The M.20/241 deposit highlights how the members of this network exercised their connection with Thon in Geneva to procure information on, and support for, their family and friends they were forced to leave. Teodor Lewite used his father’s connection to Thon whilst Maksymilian Friede used the same connection through the Polish-Palestinian Chamber of Commerce. Celina Sokołów and Mieczysław Zagajski opted for a quid pro quo type arrangement with both highlighting what they had done for Thon previously. Zofia Zelcer is the unknown quantity, the daughter of a textile merchant in the centre of Jewish Warsaw, and yet she writes candidly and emotionally to Thon of the worry she feels.

This blog post covers a small fraction of the letters in M.20/241 and relied on the generous translation and transcription of many spidery letters. This is therefore an invitation for a Polish speaking scholar to piece together the rest of the deposit from those hundreds of letters remaining and create a fuller picture of Thon’s activities in Geneva and the networks which it existed in. With so little research having been done on the activities of various groups in Geneva and the vast networks they existed in, this post has perhaps gone a little way to highlight how one of these networks was used to the advantage of those in it.

- ‘Dr Joseph Thon, Veterean Zionist, Writer, Dead’, B’nai B’rith Messenger, 16th January 1959, p.24. Many newspapers mistakenly reported his age as fifty instead. ↩

- Raya Cohen, ‘The Lost Honour of Bystanders? The Case of Jewish Emissaries in Switzerland’, The Journal of Holocaust Education, 9/2 (2000), 146-70 (p.155). ↩

- Copies of Palestyna i Bliski Wschód can be viewed online at the Jagiellonian Digital Library, Accessed via https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra, Last accessed: 6th September 2021. ↩

- For information about Friede and his family see Foreign Claims Settlement Commission of the United States. Semiannual Report to the Congress (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1964), pp.49-54. ↩

- ‘Maximilian Friede Dead at 82; Partner in Seward Commerce’, The New York Times, 27th August 1969, p.43. ↩

- Obituary of Henry Sokolow, The Boston Globe, 28th January 1929, p.21. ↩

- ‘Engadiner Legenden’, Engadiner Post, 101/36, 26th March 1994, p.7. Helena Sokolow, Engadiner Legenden (Chur: Verlag Bündner Monatsblatt, 1993), pp.69-75. ↩

- Quoted in Kenneth B. Moss, ‘Negotiating Jewish Nationalism in Interwar Warsaw’, in Warsaw. The Jewish Metropolis, ed. by Glenn Dynner and Francois Guesnet (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp.390-434 (p.390). ↩

- Anna Styczyńska-Marciniak, ‘Zagajski Mieczysław’, Virtual Sztetl, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich, Accessed via: https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/biogramy/191737-zagajski-mieczyslaw, Last accessed: 7th September 2021. ↩

- Jadwiga Maurer, ‘Wspomnienia Jadwigi Maurer: Sprzed Zagłady Przy dworze Zagajskich’, Stowarzyszenie im. Jana Karskiego, Accessed via: http://jankarski.org.pl/wspomnienia-jadwigi-maurer/, Last accessed: 1st September 2021. Extract from the magazine Teraz – Świętokrzyski Miesięcznik Kulturalny, 5 (2009). ↩

- Abraham Wilner, interview 9150, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation, Riviera Beach, Florida, 1995. ↩

- See Omer Bartov, The Eastern Front, 1941-1945: German Troops and the Barbarization of Warfare (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001), pp.76-105; Alexander B. Rossino, ‘Destructive Impulses: German Soldiers and the Conquest of Poland’, HGS, 11/3 (1997), 351-65. ↩

- Roma Nutkiewicz Ben-Atar with Doron S. Ben-Atar, What Time and Sadness Spared. Mother and Son Confront the Holocaust (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), pp.31-32. ↩

- Quoted in Nasz Przegląd: organ niezależny, 17/247, 3rd September 1939. ↩

- Jadwiga Maurer, ‘Wspomnienia Jadwigi Maurer: Sprzed Zagłady Przy dworze Zagajskich’, Stowarzyszenie im. Jana Karskiego, Accessed via: http://jankarski.org.pl/wspomnienia-jadwigi-maurer/, Last accessed: 1st September 2021. Extract from the magazine Teraz – Świętokrzyski Miesięcznik Kulturalny, 5 (2009). ↩

- Abraham Wilner, interview 9150, Visual History Archive, USC Shoah Foundation, Riviera Beach, Florida, 1995. ↩

- Krzysztof Urbański, The Martyrdom and Extermination of the Jews in Kielce During World War II (Kielce, Poland) (Kielce: n.p, 2005), Translation of the original Zagada ludnosci zydowskiej Kielc: 1939-1945 published in Kielce in 1994. Available via: https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/kielce1/kielce1.html#TOC, Last accessed: 1st September 2021. ↩

- Letter from Maksymilian Friede to Joseph Thon, 30th January 1940, M.20/241/17. ↩

- ‘Cicurel and Barda’ is listed in Davison’s Textile Blue Book (New York: Davison Publishing Co., 1924), p.1381. Leon, his brother David (1891-1977), and their partner Joseph Jacques Barda are also listed in Le Mondain Egyptien (Cairo: F. E. Noury & Fils, 1941), pp.95, 119. ↩

- ‘Kompleks Fabryczny Widzewska Manufaktura SA’, Wirtualna Lodz, Accessed via: http://www.historycznie.uni.lodz.pl/wima.htm, Last accessed: 22nd August 2021. ↩

- For more information on Widzewska Manufaktura, see Mariusz Kulesza, ‘Wielokulturowe dziedzictwo Łodzi a współczesny krajobraz miasta’, Studia z Geografii Politycznej i Historycznej, 2 (2013), 11-46 (pp. 21-22). ↩

- Letter from Maksymilian Friede to Joseph Thon, 13th February (1940), YVA M.20/241/14-16. ↩

- Letter from Maksymilian Friede to Joseph Thon, 16th February 1940, YVA M.20/241/11-12. ↩

- Letter from Leon Cicurel to Joseph Thon, 12th March 1940, YVA M.20/241/113. ↩

- Ludwig’s name appears in Louis Falstein, The Martyrdom of Jewish Physicians in Poland (New York: Exposition Press, 1963), p.303. See Irena, Ludwig and their son Edward in the Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names. ↩

- Outward Passenger List, TNA Series BT27-147369; Declaration of Intention for Citizenship, National Archives of Philadelphia, 4713410/ RG-21/ Box 410/ No.533251. ↩

- Letter from Maksymilian Friede to Joseph Thon, 13th February (1940), YVA M.20/241/14-16. ↩

- Ben-Atar, What Time and Sadness Spared, p.41; Letter from Teodor Lewite to Joseph Thon, 9th February 1940, YVA M.20/241/24-25. Lewite arrived in Haifa on 16th May 1940, ‘Warsaw Jewish Leaders Reach Palestine’, The Australian Jewish Herald, 6th June 1940, p.7. ↩

- Letter from Teodor Lewite to Joseph Thon, 9th February 1940, YVA M.20/241/24-25. ↩

- Letter from Teodor Lewite to Joseph Thon, 20th May 1940, YVA M.20/241/22-23. ↩

- Sokolow, Engadiner Legenden, p.73. ↩

- Letter from Teodor Lewite to Joseph Thon, 20th May 1940, YVA M.20/241/22-23. ↩

- Letter from Teodor Lewite to Helena Sokolow, 16th January 1940, YVA M.20/241/31-32. ↩

- Outward Passenger List, TNA Series BT27-139108. See brief entry for Teodor in I. J. Carmin Karpman, Who’s Who in World Jewry: A Biographical Dictionary of Outstanding Jews (London: Pitman Publishing, 1972), p.546. ↩

- See ‘Hitler’s Black Book – Information for Celina Sokolov’, Forces War Records, https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/hitlers-black-book/person/60/celina-sokolov, Last accessed: 18th July 2020. Celina is listed in the 1939 Register as living at 43 Compayne Gardens with her brother Leon (1889-1959), sister Helena (1894-1948) and a maid, TNA RG 101/246C. ↩

- Letter from Celina Sokolow (Sokolov) to Joseph Thon, 26th April 1940, YVA M.20/241/47. ↩

- Stephen attended Rugby School from January 1938 till the Summer of 1939. See Alan H. Maude, Rugby School Register 1911 – 1946 (Rugby: George Over Ltd.,1957), p.466. Accessed via: https://rugbyschoolarchives.co.uk/authenticated/Browse.aspx?BrowseID=15&tableName=ta_schoolregisters, Last accessed: 13th September 2021. ↩

- ‘Grandson of Nahum Sokolow Safe After Evading Germans in Poland and Austria for 5 Years’, JTA Daily News Bulletin, 17th May 1945, p.2; The Palestine Post, 24th May 1945, p.4. ↩

- Letter from Zofia Zelcer to Joseph Thon, 15th May 1940, YVA M.20/241/67-68. ↩

- Letter from Zofia Zelcer to Joseph Thon, 9th October 1939, YVA M.20/241/76; Letter from Zofia Zelcer to Joseph Thon, 20th October 1939, YVA M.20/241/72-75. ↩

- Letter from Zofia Zelcer to Joseph Thon, 17th November 1939, YVA M.20/241/71. ↩

- See Bronia Zelcer in the Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names. ↩

- Letter from Mieczyslw Zagajski to Joseph Thon, 9th April 1940, YVA M.20/241/63. ↩

- Letter from Joseph Thon to Mieczyslw Zagajski, 15th April 1940, YVA M.20/241/62. ↩

- Maurer, ‘Wspomnienia Jadwigi Maurer’; See the Zagajski family entries in the Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names. ↩