For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

Kherson is a large city in southern Ukraine and the regional center of the Kherson region. After the Germans occupied the city in August 1941, they established a Jewish ghetto in the city. Yet, eighty years later this very real story has become an urban legend of sorts. Even a few years ago, when I was telling people about the ghetto, I heard in response that “it was all a fabrication and there was no ghetto.” Indeed, there are almost no witnesses left in the city who could tell you where the ghetto was. Very few can tell when and how the Nazis created the ghetto or how they destroyed it. Few are left to tell the stories of the people who were there were or their fates. That’s why it was important to research this topic and bring it back into the public discourse.

Occupation and Genocide

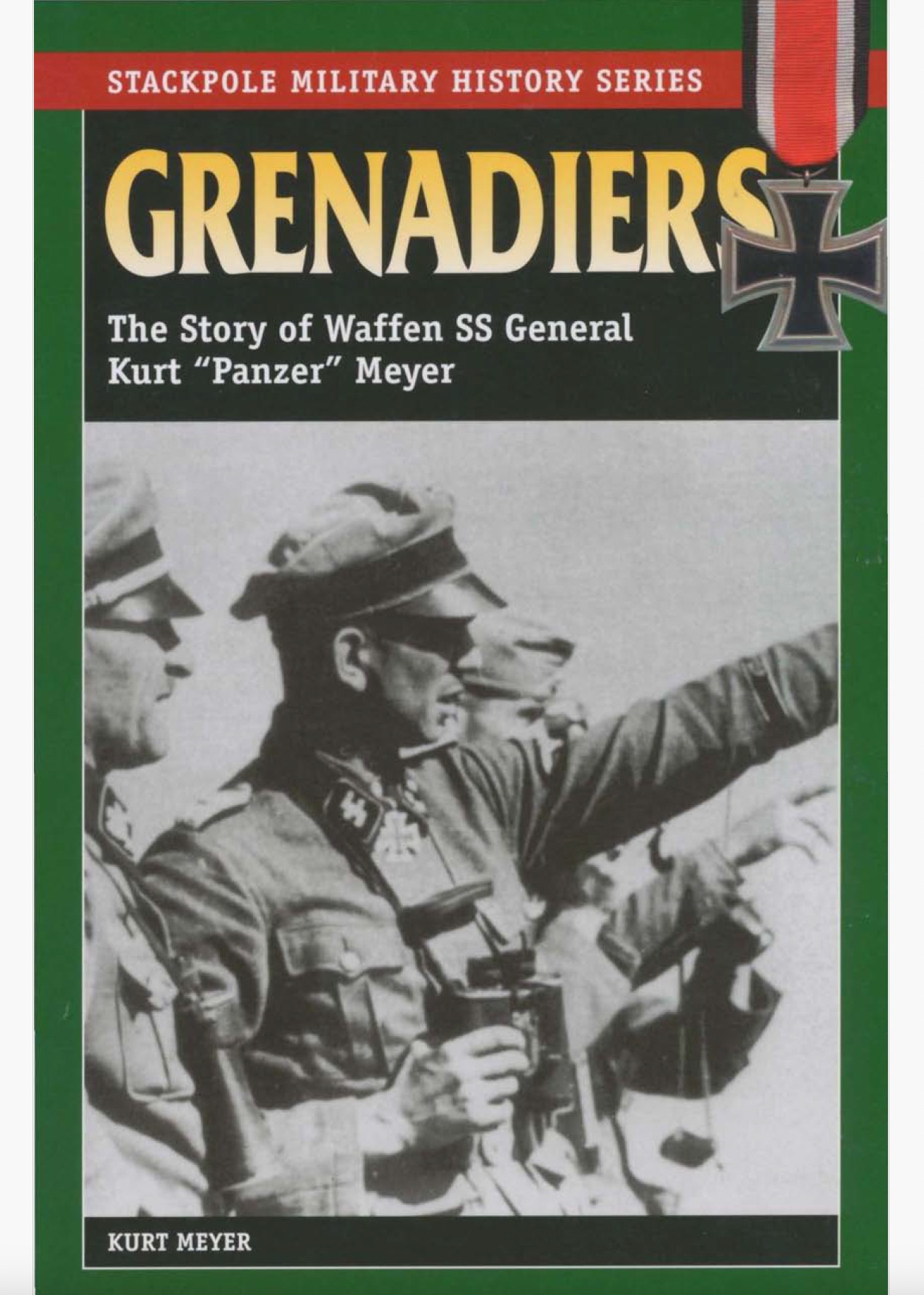

On August 19, 1941, Wehrmacht troops entered the city of Kherson (regional center of the contemporary Kherson Oblast). When reflecting on the invasion and occupation, Waffen-SS General Kurt Meyer wrote in his memoirs:

“The skyline of Cherson could be made out on the horizon. Grain silos towered over the Dnepr. The western area of the town was full of tall chimneys. Tall, shady trees beckoned in front of us. The sun had scorched us. We looked forward to water and shade in the town. A few kilometers outside of Cherson I stood on an armored car for along time and observed the town lying before us. Busy traffic was moving in an east-west direction on the river. Gunboats flitted back and forth. Large ferries steamed at a leisurely pace to the far bank, discharged their loads and returned to Cherson. The city seemed close enough to touch. It enticed, it touted itself, and seemed to mock my hesitation… Modern high-rises rose in front of us. Enemymachine-gun fire ripped up the earth around us. The struggle for Cherson had begun.”1

The fierce battle with the retreating Red Army units lasted until 16:00. During street fighting, artillery, and mortar fire, large fires broke out, especially in the harbor area, where the last evacuation ships and boats with the military were being sent away from. Thus, by the end of the day, German troops had captured the city. On August 20th, Sonderkommando 11a of the Eisantzgruppe D arrived in Kherson. Nazi administrators charged the team with executing the “final solution to the Jewish question” in the city. For the majority of local Jews, this meant a mass shooting-the Holocaust by bullets.

According to the 1939 census, 16,145 Jews resided in Kherson (the total population was 96,987 people).2 This means that the Jewish population of the city was up to 20%. Some of them managed to evacuate to the eastern territories of the Soviet Union before the Wehrmacht’s arrival, although the Soviet authorities did not make any special arrangements for this. On June 26, 1941, the Republican Evacuation Commission was established in the Ukrainian SSR. The next day, a resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR “On the Procedure for the Removal and Placement of Human Contingents and Valuable Property” was issued. Enterprises that produced products of strategic importance, raw materials, components, semi-finished products, food, machinery, agricultural grain, implements, and livestock were subject to priority relocation to the deep rear. Among the civilian population, the Party of the Soviet Union nomenklatura, and young people of military age were subject to priority evacuation. As a result, several thousand Jews remained in occupied Kherson. These were mostly people who could not organize their relocation or simply could not evacuate: the poor, the elderly, those deemed unfit for military service, women with children whose husbands were at the front, and others. Raisa Kuchereko, a resident of Kherson, recalled that “some Jews in our yard were optimistic… One lonely elderly Jew said that the Germans were a cultured nation, and they would not touch the Jews … Later he also ended up in the ghetto.”3

On August 23, 1941, the Sonderkommando established a Judenrat (Jewish Council) in Kherson. The Nazis placed prominent local Jews at the head of the council. They used their authority to keep a control of the Jewish population. In the testimony recorded for the USC Shoah Foundation Institute Visual History Archive, Boris Borisenko recalled his father’s work on the committee:

Modern view of the streets where the ghetto was located. Yurii Kaparulin.

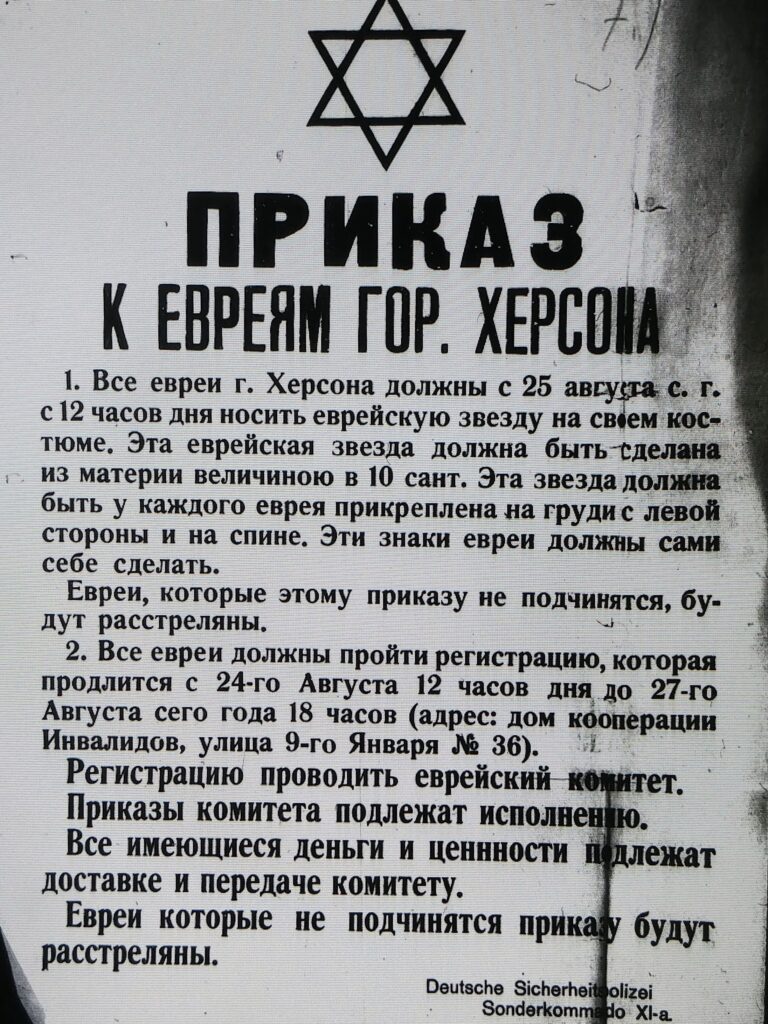

“The Jewish Committee was created on January 9th. The Germans ordered every Jew to wear a hexagonal star on the front and back. My father went, registered, and worked on this committee. He also wore such stars. The Germans often went to the committee for all sorts of things. For example, one officer needed a carpet. Then they searched among the Jews who had it and brought it to them. And they came to us. We had a rug over our bed, and they took it away too. It was done by the Jews themselves. My mother took it down and took it to the committee… My father had a wristwatch… The German in the committee saw this watch on his hand and took it away. When he came home, I asked him where it was and he told me the Germans had taken it off.”4

Soon members of the Sonderkommando drafted and distributed an order to the Jewish population of the city. Jews were ordered to sew a “Jewish star” on the front and back of their clothes. Failure to comply with this and other orders was punished by shooting. Then they were relocated to the ghetto. It was located in the area of the so-called Forshtadsky Streets (modern streets Forshtadskaya, Girsky, Mozolevsky, and Mayakovsky). At the start of September, a ghetto was created there.5 Grigory Istkovich, who escaped from Stalag 305 prison camp in Kryvyi Rih and came to Kherson to see his sister Tsila, said: “I personally saw how Jews were taken to the ghetto. I came with my sister Tsila and she told me to run away because all the Jews from the first street had already been taken away…”6 Thus, the ghettoization phase was completed. Every day people had to work forced labor.

According to the reports of Sonderkommando 11a, from August 22 to September 10, 1941, there were several massacres of Jews. The purpose of these actions was to intimidate the local population to counteract any sabotage and/or partisan movements. The massacres occurred throughout the city. and After the war, the Park dedicated to the “Glory of Victory in Great Patriotic War” was built on one of these sites. It is possible that groups of people were taken directly from the ghetto to be shot.

At the end of September, the Jews were told that they would be transported to Palestine. From September 24 to 25, the ghetto was liquidated and the Jews were transferred to the city prison. Klavdia Didenko was an eyewitness of these events:

“I remember two blocks of Forshtadsky Streets being surrounded by barbed wire… It was a very hot summer and they were not given water… I remember the day they were ordered to take all their belongings and told they would be evacuated. They were driven in columns through Freedom Square. Where Lenin’s pedestal stands, there is an empty square. They were driven to the ramparts of the fortress. Today it’s Komsomol Park, but back then it was just the ramparts. Two big pits were dug there. When the Jews saw that they were being led to these pits they started throwing out their things. They were picked up by the Schutzmann. Some Jews were hugging children and some were pushing them out of the column.”7

In the following days, the Nazis and their collaborators began mass murdering Jews. They marched the Jews on foot to the edge of the city. From there, they transported them in groups by trucks to the anti-tank ditches near the village of Zelenivka, where the execution took place. According to forensic medical examinations, the bodies of about 8,000 people were found in the mass graves. After the shooting, the Nazis used this place to bury prisoners of war from the camps established in Kherson. In the September 26th report from Einsatzgruppe D from Mykolaiv, they wrote written down that “at this moment the Jewish question in Mykolaiv and Kherson is being solved. Approximately 5,000 Jews have been captured.”8 On October 2, 1941, the command of group D reported that “the towns of Kherson and Mykolaiv were free of the Jews.”9

During the post-war investigations against Nazis in Soviet Ukraine and abroad, the names of most of the war criminals responsible for the mass murder of Jews from Kherson were unknown. Some of the perpetrators managed to evade responsibility for many years. For example, the commander of Sonderkommando 11a, Paul Johannes Zapp, was arrested in Germany only in 1967. During his trial in Munich, he never repented of what he had done, claiming that he had acted “in the spirit of the times.”10

Investigating the Crime

On March 13, 1944, Kherson was liberated from German occupation. Almost at once the Extraordinary State Commission began its work in the city and region.

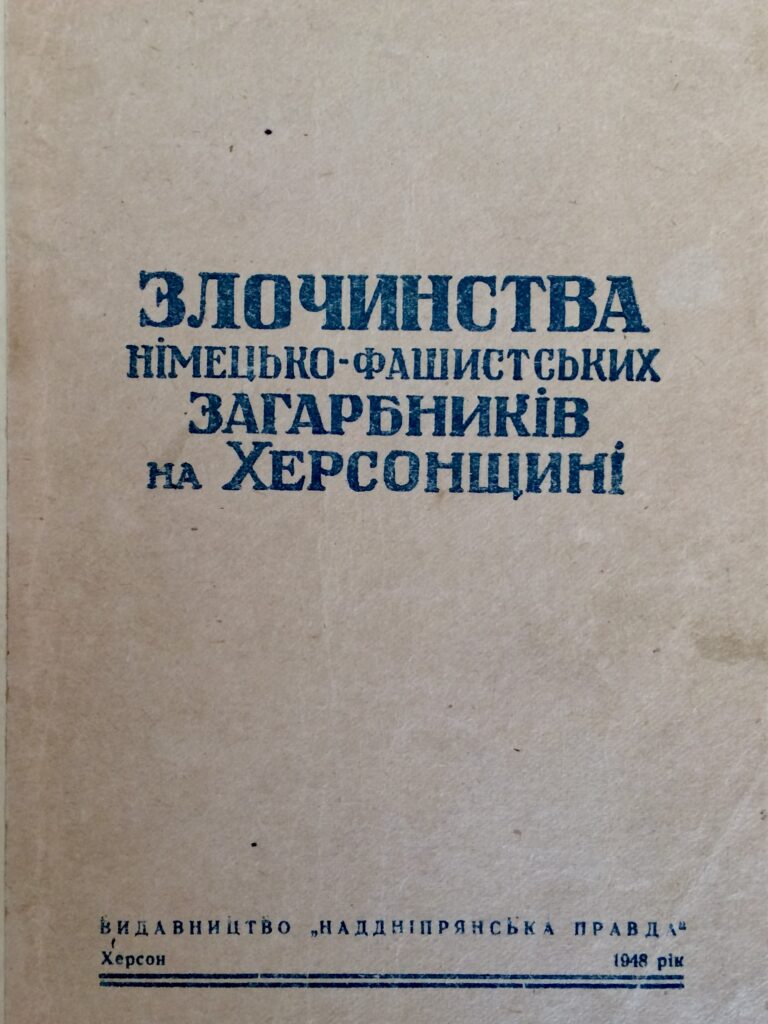

The commission’s investigation recorded the facts of mass murders committed by the Nazis in the formerly occupied territories. Holocaust researchers have repeatedly pointed out that the investigators sometimes ignored the ethnic or social status of the victims and referred to them generically as “peaceful Soviet citizens.” However, in Kherson, the victim’s Jewish nationality was not excluded from the documentation. Moreover, in 1948 the publishing house Naddnipryanskaya Pravda published selected documents of a commission in which the Jewish victims were listed as a separate category along with the Soviet employees, Roma, patients of the local psychiatric hospital, and prisoners of war:

“Terrible crimes were committed by the Germans against the Jewish population of the city.11 On September 23, 1941, the Germans drove more than 8,500 Jews out of the town in automobiles and shot them all on the grounds of the agricultural colony … In the middle pit, of the same size as the previous one, at a depth of one and a quarter meters, the corpses of men, women, and children were also found in the same various poses. The corpses are flattened between each other, lying one on top of the other. There is no earth layer between the corpses. On the clothes of some corpses on the chest and back the six-pointed stars made of yellow cloth were sewn… On the basis of the above, the testimony of witnesses and documents, and material evidence found in the graves, the commission established the fact of the extermination in September 1941 by the German occupation troops of the peaceful Soviet citizens of Jewish nationality, as well as prisoners of war in a total number of 8780 people.”12

The testimonies of witnesses gathered by the commission also repeatedly mentioned the establishment of the Jewish ghetto in Kherson. All this shows that the work of the investigators in Kherson was not intended to completely conceal the Jewish experience during the occupation.

However, the situation changed radically in the following years. In 1948, an antisemitic unspoken campaign was launched, accompanied by the dismissal and arrest of many Jews. In particular, many members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested and later shot. At the same time, an official Soviet model of memory about World War II began to take shape. There was no place in it for individual categories of Nazi victims. The main emphasis was placed on the heroism and sacrifice of the entire Soviet people as a whole.

Thus, many such documents remained inaccessible to researchers for decades. For example, only recently was it possible to find and publish the diary of a resident of Kherson, who described his observations of the initial period of occupation and the creation of a Jewish ghetto in the city.13

Reviving the Memory

Critical revision of the past became possible only after the fall of the USSR and the achievement of Ukrainian independence. On the other hand, going beyond the Soviet ideology and narratives took many years, and in some issues lasts until today.

Mainly in the families of the rescued Jews preserved the memory of Holocaust in Kherson for decades and began to return to the public space with the revival of the city’s Jewish community at the end of the 1980s. In 1988 a religious community “Chabad” was created in Kherson and the Society of Jewish Culture followed in 1989. In 1990, to meet the Jewish community’s needs, community managed to reclaim one of the old synagogues in Kherson that had been requisitioned by the Soviet authorities in the 1920s.14

One of the community leaders from the early 1990s, Semyon Modijewski, began collecting memories on the Holocaust in Kherson and the Kherson region during the 1990s, which were later published in Israel. Today, this work is continued by the staff of the Hesed Shmuel Jewish Charity and Community Center, headed by Alexander Weiner. The chief rabbi of Kherson and the Kherson region, Yossef Yitzchak Wolff, has for many years held memorial days for members of the community at the sites where Nazi war crimes took place.

At the same time, the history of local Jews has long remained little known to the general public outside the Jewish community. A landmark event was the publication in 2004 of Boris Nepomniashchy’s book Jewish Kherson, which drew the attention of the public and researchers to the history of the city’s Jews and the genocide during World War II.15 The study of the Holocaust in Ukraine began at Kherson State University, of which Boris Nepomniashchyi was a graduate. However, it took years before the first academic studies appeared on the local level, using a specialized approach to the study of the topic using a broad base of sources.

Solar power plant near the place of execution. Les Kasyanov, Yurii Kaparulin

Unlike other large Ukrainian cities where Jewish ghettos existed, Kherson’s memorial space rarely reflects the history of the city’s Jews. The only reminder of the Kherson ghetto is a small memorial plaque on the old building of the Tropinykh Hospital. There is an inconspicuous Soviet-era monument dedicated to “Soviet civilians and prisoners of war” at the site of the shooting of the Jews near Kherson. In 2017, the Tryfonivska solar power plant was built on the territory adjacent to the place of execution, which was partially damaged during the occupation of Kherson by Russian troops in 2022. Today, these memorial sites are threatened by daily shelling by the Russian army, which continues to destroy Kherson and kill its residents after the city was de-occupied by the Armed Forces of Ukraine in November 2022.

Thus, the study of the history of the Kherson Ghetto today is not only of academic interest but there is also the problem of creating a modern memorial public space that could serve the purpose of preserving the memory of Holocaust victims and survivors. At the same time, we should continue a public dialogue about this tragic human experience, to facilitate the search for and restoration of the truth about the past. There we can more effectively promote human rights and resist the possibility of a repetition of mass violence in our time. Public history approaches can help us to do this.

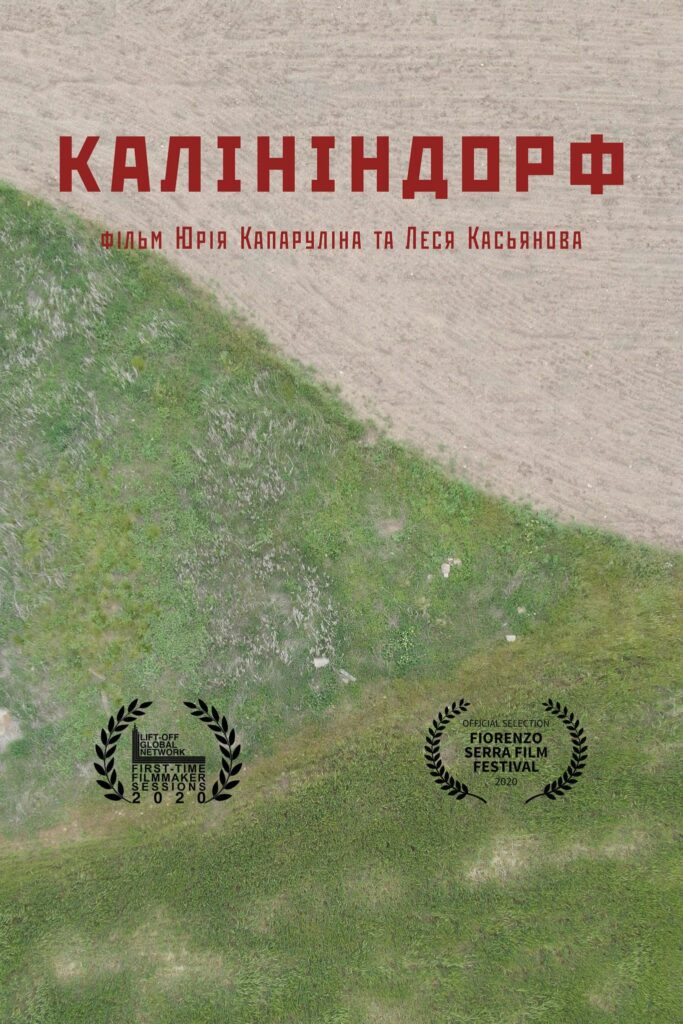

The history of the Jews of Kherson is directly related to the fate of the Jews who lived in the countryside near the city, particularly in the Kalinindorf district. In 2019, my colleague Les Kasyanov (photographer, director, member of Yahad-In Unum expeditions) and I made a documentary film about the tragedy of the Jews of Kalinindorf (modern Kalinovskoye village, Kherson region). The documentary Kalinindorf was presented during an all-Ukrainian tour in Kyiv, Dnipro, Rivne, and Kherson in 2020. The film participated in several prestigious documentary film festivals. As the authors, we were impressed by the interest of the audience and the questions during the discussion of the film. We have received positive feedback, particularly from experts in Holocaust history research. For example, Wendy Lower noted that “Yurii Kaparulin and Les Kasyanov have created a striking documentary.”16

Posters of documentaries. Les Kasyanov

After this experience, we decided to continue the work and started a new documentary project titled (Un)Known Holocaust in 2021. In several episodes of the film, we plan to tell the story of certain categories of victims of the Nazi regime in Kherson: Jews, Roma, Prisoners of War, and patients of local psychiatric hospital.17

We presented the first part of the film (Un)Known Holocaust: Southern Ghetto at a meeting of the Kherson City Council in September of 2021. Our main audience was the deputies and the press. Using this, we drew officials’ attention to the upcoming 80th anniversary of the Holocaust tragedy in Kherson. This initiative was supported by the mayor of the city, Igor Kolyhaev. The meeting was attended by representatives of the Jewish community of the city. In my speech to the deputies, I reminded attendees of the fact that remembrance of the Holocaust is one of the foundations of modern European identity and that the streets in the city where the ghetto was should be properly marked. In the years to come, we hope that this discussion will not only help to recover and preserve the memory of the genocide but will also promote concrete projects of memorialization. Of course, all of these plans were disrupted by the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation and are now postponed for an indefinite period. The mayor of the city, Ihor Kolikhayev, and many other Kherson residents are still in Russian captivity. Some local officials have cooperated with the Russian occupation authorities, actualized the phenomenon of wartime collaboration. Perhaps this facts will help in the future to study the phenomenon of collaboration in more detail at the local level also during the Second World War.

It is also worth noting some established practices that contributed to the lack of attention to the memory of Holocaust victims in the city for many years. For example, until recently, every September in Kherson and many other cities in Ukraine there are events to prepare and celebrate the city day. On about the same days, the local Jewish community organizes memorial days in honor of Holocaust victims. Usually, these events take place independently, and the publics attention is more focused on the city-wide holiday events. In 2021 we proposed to the mayor of Kherson and the deputies of the city council to organize a public showing of our film as part of the event for the city day. For this purpose, we were given time in the central cinema of the city “Yuvileinyi.” Many university students, school pupils, teachers, scientists, and simply interested city residents came for the screening. We were sure that the City Day celebrations were not only an occasion for entertainment but also an opportunity to draw the city’s citizens’ attention to important events in local history and to discuss topics of social importance. Seems that worked.

On January 27, 2022, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we hosted an online presentation and discussion of the first episode of the film (Un)Known Holocaust: Southern Ghetto. In recognition of the importance of the educational component of Holocaust studies, we have made the film freely available on YouTube for teachers and educators to use in their classes. In this way, we have created a resource that can be used as a source for studying the history of the Holocaust in schools and universities.18

Human experience shows that even the worst crimes against humanity and genocides and their consequences can be forgotten. Without the education of young generations, the risk of violent repetitions begins to increase again. This is evidenced by the shameful incident that took place in Kherson on April 20, 2020, when two young men at night, using Molotov cocktails, attempted to set fire to the synagogue, which belongs to the Chabad Jewish community in Kherson. They were soon detained and explained that they wanted to celebrate Hitler’s birthday this way.19 However, it should be noted that this is not a typical case. It shocked many locals and led to condemnation of this manifestation of antisemitism and any other possible cases of xenophobia. Therefore, it is extremely important to me, as a university professor, that young people be educated about these issues.

In 2020, the Raphael Lemkin Center for Genocide Studies was established at Kherson State University. The center aims to conduct research and educational activities for students from the different specialties and educational institutions in Kherson. During the period of our work, we carried out several events devoted to such tragic events as the Holodomor, the Holocaust, the Genocide of the Crimean Tatar people, and other mass crimes. For example, we initiated an annual commemorative excursion Through the Streets of the Kherson Ghetto. In the fall of 2021, together with the cadets of the Kherson State Maritime Academy, we talked about the regional particularities of the Holocaust in Kherson and about the importance of developing zero tolerance for xenophobia, especially among future sailors.

Kherson after the Russian occupation, 2023. Petro Kobernik.

We had a lot of plans for 2022, but the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation has destroyed them. Eighty years after the Second World War, Kherson was occupied again and new war crimes were committed in the places where the Holocaust took place. After the de-occupation of the city on November 11, 2022, the Ukrainian side began investigating crimes committed by the Russian occupation authorities. As of the beginning of March 2023, a total of 1,213 episodes involving human losses or violations of rights among the civilian population were recorded, including deaths, injuries, rape, rights violations, kidnapping, and others.20

Afterword

Today, every Ukrainian feels the impact of war. My family, like millions of Ukrainians, was forced to leave their home in Kherson. As of this writing, hundreds of thousands of my compatriots remain in danger in the occupied territory, and thousands have already died in various regions of Ukraine due to the aggression of Russia. The whole world became aware of the facts of war crimes committed in Bucha, Irpin, Mariupol, Kharkiv, Kherson, and other places. At the same time, millions of Ukrainians remain united, consolidated and with faith in the victory of liberty and democracy. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians have taken up arms and are defending these values daily at the risk of their own lives. What the memory of the Holocaust and other tragedies of the past will be in Kherson and Ukraine now all depends directly on the outcome of this brutal and criminal war. Once again, I ask myself how much the past can influence the present. Russia’s current aggression, which is based on the propaganda of a simplified, distorted, and mythologized view of history, proves that history can be a mighty and destructive weapon.

- Kurt Meyer, Grenadiers: The Story of Waffen SS General Kurt ‘Panzer’ Meyer, (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005), 93-94. ↩

- “Vsesojuznaja perepis’ naselenija 1939 goda, Nacional’nyj sostav naselenija rajonov, gorodov i krupnyh sel sojuznyh respublik SSSR,” Demoskop: demograficheskij jelektronnyj zhurnal, http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/ussr_nac_39_ra.php?reg=306, accessed September 15, 2023. ↩

- Testimony of Raisa Kuchurenko, Visual History Archive (VHA) 46908. ↩

- Testimony of Boris Borisenko, VHA 43106. ↩

- Yurii Kaparulin, Chronicle of the Kherson Ghetto (1941), in City: History, Culture, Society, 9:2, 2020, 88–104. https://doi.org/10.15407/mics2020.09.088. ↩

- Testimony of Grigorii Itskovich, VHA 49512. ↩

- Testimony of Klavdiia Didenko, VHA 43299. Accessed online at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum on (Jan 25 2019). ↩

- Aleksandr Kruglov, Sbornik dokumentov i materialov ob unichtozhenii natsistami evreev Ukrainy v 1941-1944 godakh, (Institut iudaiki, Kiev, 2002), 76. ↩

- Ibid, 77. ↩

- Konrad Kwiet, Paul Zapp: Vordenker und Vollstrecker der Judenvernichtung, in Karrieren Der Gewalt: Nationalsozialistische Täterbiographien. (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2004). ↩

- The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). T 314, roll 1337. ↩

- Zlochyny nimetsko-fashystskykh zaharbnykiv na Khersonshchyni (dokumenty i materialy), (Vydavnytstvo «Naddniprianska pravda», Kherson, 1948), 8, 20, 24. ↩

- Yurii Kaparulin, “Eyewitness Account of the Nazi Occupation in the South of Ukraine: Diary of a Kherson Resident” Eastern European Holocaust Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2023, pp. 215-239. https://doi.org/10.1515/eehs-2023-0018. ↩

- Evreiskyi blahotvorytelno obshchynnyi tsentr «Khesed-Shmuel», https://hesed.kherson.ua, accessed September 15, 2023. ↩

- Boris Nepomniashchyi, Kherson evreiskyi: trahedyy y sudbi, (Kherson, Oldy-plius, 2004). ↩

- Wendy Lower, Furii Hitlera. Nimetski zhinky u natsystskykh poliakh smerti (Kyiv : Ukr. tsentr vyvch. istorii Holokostu; 2020), 13. ↩

- (Un)Known Holocaust, http://leskasyanov.com/unknown-holocaust, accessed September 15, 2023. ↩

- (Un)known Holocaust. Episode II. Southern Ghetto, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qyaBSFGMpEQ, accessed September 15, 2023. ↩

- Sluzhba bezpeky Ukrainy, SBU vstanovyla osoby ta zatrymala dvokh pidpaliuvachiv synahohy u Khersoni, https://ssu.gov.ua/novyny/7585, accessed September 15, 2023. ↩

- Rik povnomasshtabnoi viiny u Khersoni ta Khersonskii oblasti: uzahalnennia podii, https://www.helsinki.org.ua/articles/rik-povnomasshtabnoi-viyny-u-khersoni-ta-khersonskiy-oblasti-uzahalnennia-podiy/, accessed September 15, 2023. ↩