Rachel Auerbach’s (1903—1976) Oyf di felder fun Treblinke – a reportazsh (In the Fields of Treblinka – a Report) from 1946 was the first book I happened to come across when I started inventorying a collection of Yiddish books in Judiska Biblioteket, the Jewish Library in Stockholm. A shiver ran down my spine when I noticed Auerbach’s handwritten dedication. Auerbach, a Polish-Jewish intellectual, played a key role in Holocaust documentation and was a witness at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961. Auerbach’s book is one of hundreds of books in the Yiddish collection, which can be considered as khurbn-literatur – Holocaust literature. Numerous dedications, ex libris, stamps, labels, signatures and other markings in the books not only testify to the origin of the collection, but also recount the life and cultural revival of the sheyres-hapleyte, or the surviving remnant, as Yiddish-speaking survivors in Sweden called themselves.

The Jewish Library in Stockholm has a collection of more than three and a half thousand volumes in Yiddish, mainly of post-World War II literature. It has been almost completely forgotten over the years. Since 1999, Yiddish enjoys the status of a minority language in Sweden and interest in the language and culture has recently increased. The aim of “Traces of Yiddishkeit” project (2020-2021), led by Södertörn University professor Lena Roos and funded by the Swedish Rikbankens Jubileumsfond, was to make an inventory of this collection.1 Almost 15 percent of the books have markings and inscriptions of previous owners and donors. They convey a sense not only of the history of the collection, but also of the cultural revival of the Holocaust survivors who settled in Sweden and their connections with the transnational survivor community. Sweden became a Nordic centre of Holocaust survivors. In 1947, when many had already migrated elsewhere, there were still about seven thousand survivors in Sweden, the same amount as the local Jewish community that had survived intact. The books with their markings are valuable historical documents in their own right. The dedications and markings in the books tell an interesting story about the origin of the books and, more broadly, about the social history of the survivor community, their exchanges and networks. In this blog I will explore the “Yiddish 30 – Nazism” category of the Yiddish collection, which contains 122 books about the Holocaust and the history of Nazism.2

During the period between the World Wars, historical research in Yiddish began to emerge in Eastern Europe. It became of great importance in the documentation and research of the Holocaust during and after the war. The most famous of the wartime research projects was the clandestine Oyneg Shabes project in the Warsaw ghetto, led by the historian Emanuel Ringelblum (1900-1944), which systematically collected material about life in the ghetto and the atrocities committed against Jews.3 This material was hidden underground in sink boxes and milk tanks. While the war was still going on, in August 1944, the Central Jewish Historical Committee was established in Soviet-liberated Lublin. The Committee moved to Warsaw via Łódź and was renamed the Jewish Historical Institute. The contents of the Oyneg Shabes material found in the ruins of the ghetto formed the heart of the institute’s archive. With the help of numerous volunteers, it also gathered a vast collection of witness statements and other material.

The “Yiddish 30 – Nazism” category in the Stockholm Jewish Library includes wartime descriptions and diaries, such as Emanuel Ringelblum’s Notitsn fun varshever geto (Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto, Warsaw 1952), as well as eyewitness accounts written after the war, such as Mashe Rolnik’s Ikh muz dertseyln (I Must Tell, Warsaw—Moscow 1965). Most of these books were originally written in Yiddish, which after the Holocaust was occasionally referred to as loshn-hakdoyshim, the language of the martyrs. There are also some books in translation, such as Anne Frank’s Togbukh fun a meydl (Diary of a Girl, Tel Aviv 1958). Most of the books were published between 1945 and 1960, which David Roskies and Naomi Diamant have called the period of “communal memory” in Holocaust literature.4 During this period, writing and discourse about the Holocaust was mainly confined to the survivor community and Jewish communities in general. The Yiddish collection in the Jewish Library in Stockholm refutes the persistent myth that the survivors were silent about their experiences; in Yiddish there was no silence about the Holocaust. Only recently have historians started paying more attention to this period and the Yiddish language literature.5 The countries where the books have been published reflect the transnational geography of the Yiddish language and the sheyres-hapleyte. Most of the books in this Stockholm-based collection were printed in the USA, Poland, Israel, France, and Argentina, but there are books also from the Soviet Union, Rumania, Canada, Mexico, Uruguai, South Africa, and Sweden.

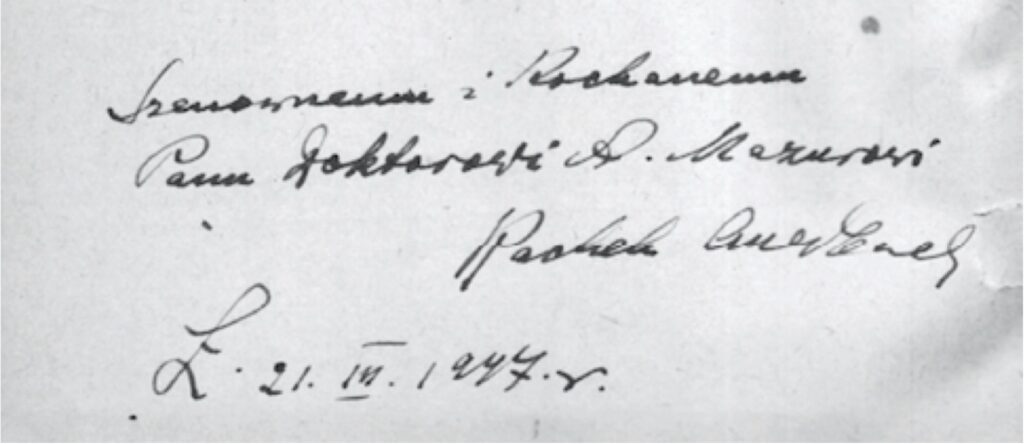

Let us return to Auerbach and her book Oyf di felder fun Treblinke. During the war, Auerbach, who studied philosophy and psychology at the University of Lwów, ended up in the Warsaw Ghetto and participated in Ringelblum’s clandestine archival project. In 1942, she wrote down an eyewitness account about Treblinka and the fate of the Warsaw Jews by a person who had escaped from the death camp. Auerbach managed to escape from the ghetto and join an underground movement. After the war, she worked for the Central Jewish Historical Commission and collected eyewitness accounts of survivors. In addition to these accounts, her book was based on her own observations during an expedition to the former camp in November 1945. Auerbach’s impressive reportage describes the death machinery of the camp, the moment the Jews were brought there, their gassing and disposal of the bodies, and the post-war desecration of the area. Oyf di felder fun Treblinke as well as her other books in Yiddish is still await translating into English. The copy of the book in the Jewish Library contains her dedication in Polish: “Szanownemu i kochanemu Pan Doktorowi A. Mazurowi, Rachel Auerbach, Ł. 21. III 1947 g.” (“To the dear and esteemed Mr Doctor A[lbert] Mazur, Rachel Auerbach, Ł[ódź?] 21 March 1947”). During the war, Albert Mazur (1913—1976) worked as a doctor in the Łódź ghetto and was, together with his wife and children, among 800 Jews left to clean the ghetto after the last deportations and saw the Soviet liberators. Mazur and his family settled in Sweden in 1946. The book was dedicated to Mazur in 1947 when he was already there. Mazur probably visited Łódź – to which the “Ł.” in the dedication could refer to – and met with Auerbach there. But is it not also possible that Auerbach visited Stockholm? A reason for such a visit could have been that Nella Rost, who had been vice-director of the Krakow branch of the Central Jewish Historical Commission, had settled in Stockholm and established the Jewish Historical Committee under the Swedish Section of the World Jewish Congress.6

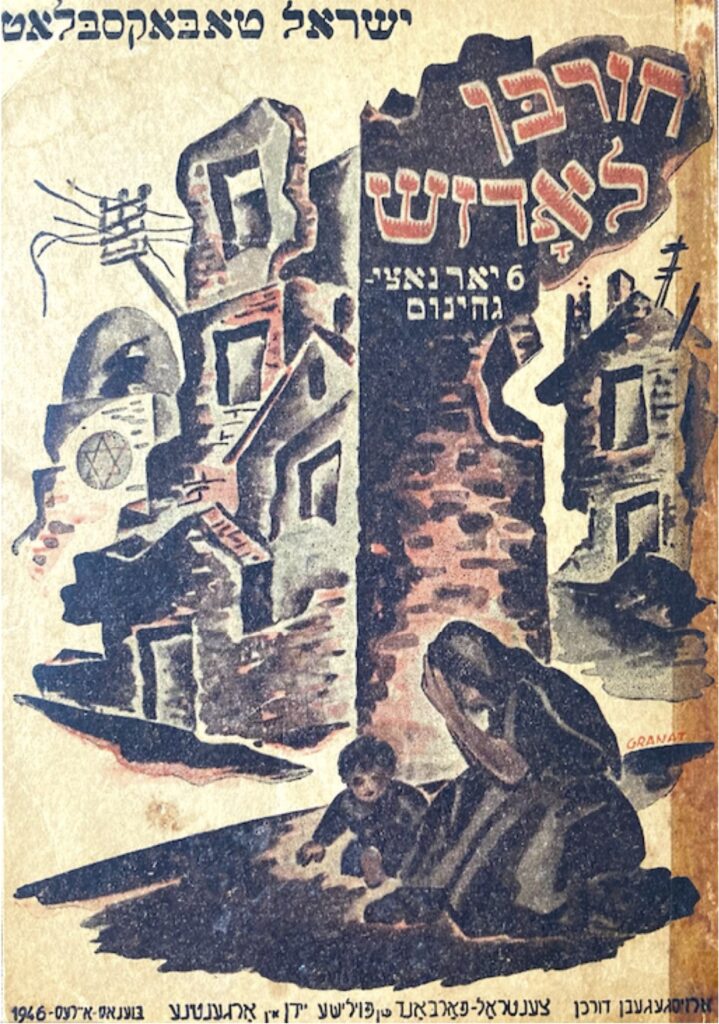

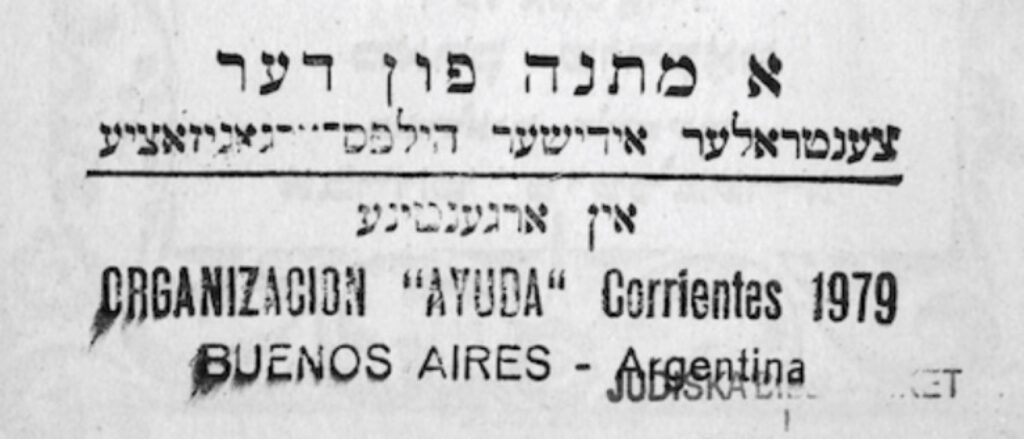

Another interesting author’s handwritten dedication from the “Yiddish 30 – Nazism” is in Yisroel Tabaksblat’s (1891—1950) book Khurbn Lodzsh – 6 yor natsi-gehenem (The Destruction of Łódź – 6 Years of Nazi Hell, Buenos Aires 1946). The book appeared in the series Dos poylishe yidntum (Polish Jewry) edited by Mark Turkow, which between 1946 and 1966 published a total of 175 books on Polish Jewish culture and its destruction, Tabaksblat’s work being the fifth.7 The most famous book to appear in the series was Elie Wisel’s Un di velt hot geshvign (And the World Was Silent, 1956; in English translation, Night, 1960). During the Holocaust, Tabaksblat was in the Łódź ghetto and worked in its administration. After surviving Auschwitz, labour camps and the death march, he returned to his hometown and finished writing his book. Khurbn Lodzsh is significant for being the first book describing the life and destruction of the Łódź ghetto. After the bloody pogrom in Kielce in the summer of 1946, Poland no longer seemed like a safe place to stay, and Tabaksblat and his wife managed to get a visa to Sweden along with some other Polish Yiddish authors, such as poets Rokhl Korn and Nahum Bomze. Before moving to Paris, Tabaksblat worked for a few months in the service of the Swedish Section of the World Jewish Congress assisting other Jewish refugees. Khurbn Lodzsh appeared when Tabaksblat was still in Sweden. The copy at the Jewish Library has a dedication in Yiddish dated October 4, 1946, in Stockholm: “Der familye Lapidus, a fraynt in der fremd – a matone” (“To the Lapidus family, friends in a foreign land – a gift”).

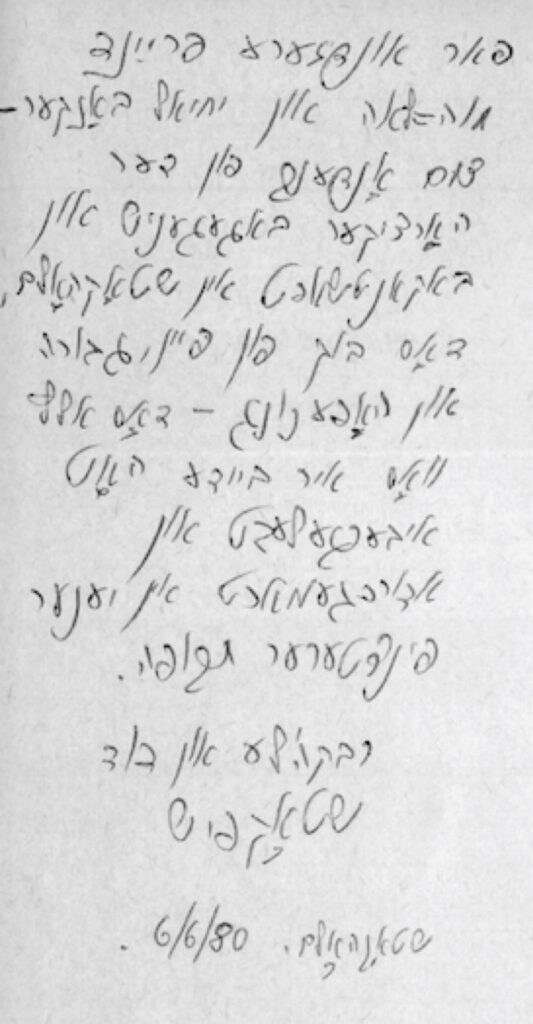

In addition to the authors’ handwritten dedications, the books in the “Yiddish 30 – Nazism” category of the Jewish Library have other dedications referencing the experiences and encounters of concentration camp survivors who arrived in Sweden. For example, Yisroel Ayzenberg’s memoir describing the Lublin ghetto, Far vos grod ikh? Kapitlen fun payn, gvure un hofnung (Why me? Chapters about Pain, Bravery and Hope, Tel Aviv 1980), has a Yiddish dedication written by the Sztokfisz couple to the Bankier couple in June 1980: “Far undzere fraynd Khave-Leye un Yekhiel Banker – tsum ondenk fun der hartsiker bagegenish un bakantshaft in Shtokholm, dos bukh fun payn, gvure un hofenung – dos alts vos ir beyde hot ibergelebt un adurkhgemakht in yener fintsterer tkufe. Rivkele un Dovid Shtokfish” (“To our friends Khave-Leye un Yekhiel Bankier – in memory of a cordial meeting and acquaintance in Stockholm, this book about pain, bravery and hope – everything you both experienced and survived during that dark period. Rivkele and David Sztokfisz”). The book has a foreword by Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer, in which he describes the work as an important addition to khurbn-literatur and states: “Unfortunately, our generation does not read enough memoirs like this. The Holocaust is too close and the pain too great.”

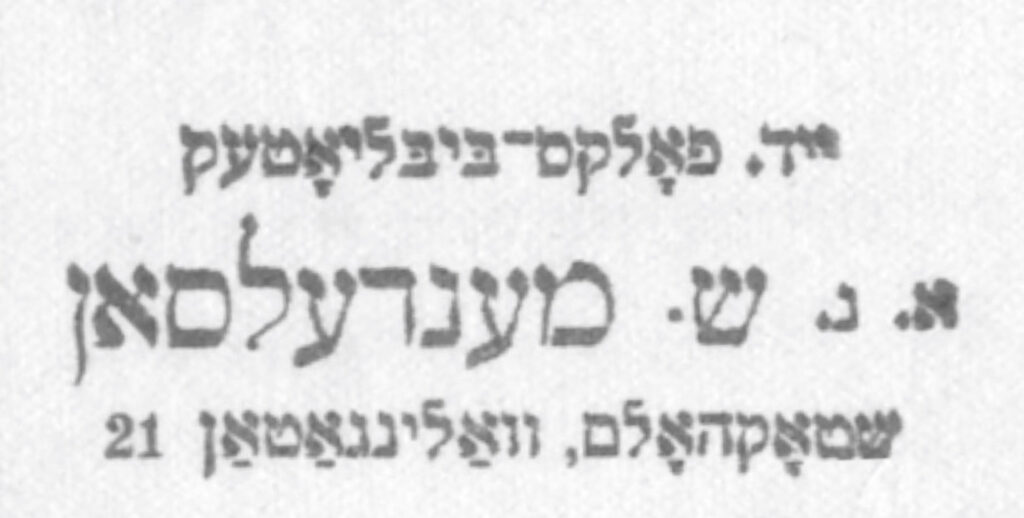

In addition to dedications, the Yiddish books in the Jewish Library in Stockholm contain plenty of stamps, labels and signatures that indicate book donations from private persons as well as organizations. After the Second World War, Jewish organizations such as the Labour Zionist Committee for Relief and Rehabilitation in New York and the Central Jewish Relief Organization in Buenos Aires sent books to the survivors in the Displaced Persons camps in Europe. The World Jewish Congress organized book collections in America, which resulted in the arrival of used Yiddish books in Sweden, some of which are now in the Jewish Library in Stockholm. The survivors themselves were also in contact with Yiddish publishers in America to obtain books. The meaning of a “Yidish vort”, i.e. Yiddish language, literature and culture was of great importance to the surviving remnant. It offered an opportunity to reconnect with their past and their culture. So testify the memoirs of the Polish Jewish actor Josef Glikson, who visited sanatoriums and convalescent homes with his wife, the actress Cypora Fajnzylber. The memoires were serialized in the Yiddish-language journal Yedies of the Swedish Section of the World Jewish Congress in Stockholm in 1948. While visiting Saleboda in Southern Sweden, Glikson borrowed a book from the survivors’ tiny but precious library. The residents watched over their book collection like the apple of their eye. Glikson writes that when he left, “at least half a minyan [quorum of the men] of Saleboda residents asked if I had by any chance forgotten to return the book”. The stamps also bear witness to previous Yiddish libraries that operated in Sweden, which, after closing, handed over their books to the Jewish Library. The most well-known of these is probably the Yidishe folks-bibliotek, Jewish Public Library, of the Jewish social-democratic labour party Bund.8 The library was named after the Polish Bund leader Shloyme Mendelson and was located at Wallingatan 21 in the centre of Stockholm. The vigorous activity of the Bund in Sweden was short-lived, and the book collection ended up in the collections of the Jewish Library.

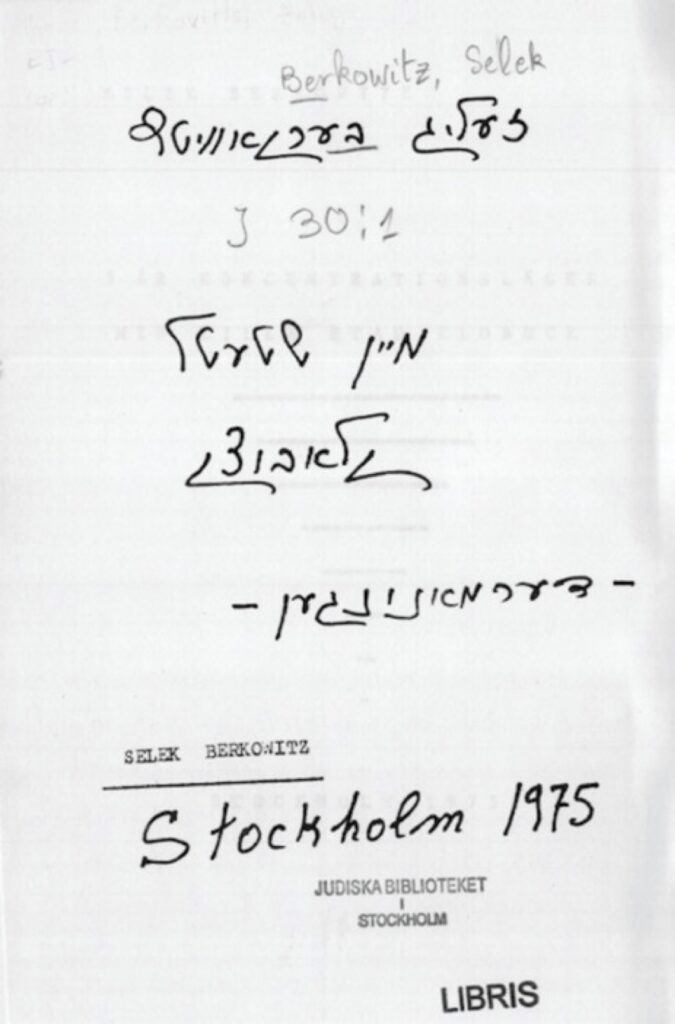

Although all the books in the “Yiddish 30 – Nazism” category can be found in the Worldcat catalog and in libraries around the world, there are also rarities whose circulation was very small. Such are, for example, the books of two former Łódź residents, Ludwig Winograd (1895—1980) and Selek Berkowitz (1912—1989). Both works were self-published. They were written on a Yiddish typewriter, after which the pages were duplicated by hand and stapled into books. The books bespeak the difficulties in finding Yiddish-language publishers and printers, as well as the authors’ strong desire to be heard.

Winograd’s book Mayn lebns veg: Lodzsh, milkhome-yorn, Shvedn, Argentine, Miami-Bitsh (The Road of My Life: Łódź, War Years, Sweden, Argentina, Miami Beach) was published in Miami Beach in 1978.9 At almost 400 pages, it describes Winograd’s life before the war in Łódź, the ghetto, surviving Oranienburg concentration camp and returning to Łódź, where he also got to know Auerbach. In 1946, Winograd arrived with his daughter Dziunia in Stockholm, to which he devotes twenty pages of his book. Winograd describes how some of their traveling companions kissed the deck of the ship taking them to Gothenburg out of joy and relief for leaving behind Poland that had brought them “more suffering than happiness”. Winograd’s brother-in-law and his wife had already settled in Sweden before the war, but the happy reunion turned into great sadness when the relatives heard first-hand about what happened to the family during the Holocaust. The book offers an interesting cross-section on the lives of the Jewish refugees who arrived in Sweden and their desire to start a new life. Winograd also writes about his cooperation with Paul Olberg, the leader of the Swedish Bund, and other supporters of the party. However, Winograd left the “beautiful, free and democratic Sweden” behind and moved to Argentina in 1947. He had close friends in Buenos Aires and the idea of a large Jewish community with a rich Yiddish-speaking cultural life appealed to him. Winograd published articles in many magazines, e.g. in Undzer gedank in Buenos Aires and Lebnsfragn in Tel Aviv. Eventually, however, Winograd escaped Argentina’s political instability in favor of Florida.

Berkowitz’s book Mayn shtetl Klobutsk – dermonungen (My Town Kłobuck – Memoirs), which he published in Stockholm in 1975, is a true rarity, as one of the few Yiddish books written and published in Sweden during the 20th century. Despite the title, the main part of the book constitutes Berkowitz’s own testimony. He describes how the idea of writing about his experiences tormented him at night until he took action. Berkowitz, like Winograd, was a resident of Łódź, but managed to escape the ghetto before it was sealed-off. He returned to his hometown of Kłobuck, located near Częstochowa, but was soon taken into forced labor. In his book, he describes the suffering and death in the concentration camps of Annaberg, Grünheide, Markstädt, Fünfteichen, Gross-Rosen, Flossenbürg and Ansbach. After liberation, Berkowitz followed his wife to Sweden, where she had been taken from Bergen-Belsen during the relief actions in 1945. Berkowitz held a prominent role in the Yiddish-language culture in Sweden. In the 1970s he became the co-editor of journal Yidish kultur in Skandinavyen (Jewish Culture in Scandinavia).

Berkowitz’s book, like many of the other books in the “Yiddish 30 – Nazism”, is not an easy read. Even though Auerbach notes in her introduction, that Oyf di felder fun Treblinke is not for “menthsn mit shvakhe nervn”, people with bad nerves, she pleads the readers: “Every Jew should know that it is their national duty to know the truth. And whether they want to know or not, they should be encouraged in all possible ways to make the truth known also among non-Jews.”

As the above testifies, the books in the Yiddish collection with the dedications, stamps and labels are valuable historical documents in their own right, and we can learn about the social history of the survivor community in Sweden, their exchanges and networks. All in all, the Yiddish book collection of the Jewish Library in Stockholm is an important record of the survivor generation’s way of dealing with the Holocaust and opens interesting new perspectives for research.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Malin Norrby and David Raichel from the Jewish Library in Stockholm for the scans of the books.

- http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/project.jsf?pid=project%3A2062&dswid=9366 ↩

- One can search the collections of the Jewish Library in Stockholm through the Libris database of Kungliga biblioteket, http://libris.kb.se. In the extended search, for ‘Library’ add ‘JUD’ and in ‘Language’ choose ‘Yiddish’. In addition to the Yiddish 30 – Nazism category the Yiddish collection has a lot of poetry and fiction that deal with the Holocaust. ↩

- Samuel D. Kassow, Who Will Write Our History: Emanuel Ringelblum, the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Oyneg Shabes Archive (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007). ↩

- David G. Roskies and Naomi Diamant, Holocaust Literature: A History and Guide (Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2012), 75-124. ↩

- See for instance, Laura Jockusch, Collect and Record! Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe (Oxford – New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Mark L. Smith, The Yiddish Historians and the Struggle for a Jewish History of the Holocaust (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2019). ↩

- About Nella Rost, see Johannes Heuman, “In Search of Documentation: Nella Rost and the Jewish Historical Commission in Stockholm,” in Early Holocaust Memory in Sweden: Archives, Testimonies and Reflections, ed. by Johannes Heuman and Pontus Rudberg, 33-65 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021); Jockusch, Collect and Record!, 5, 91-95, 103-104, 120, 168, 182, 218. ↩

- On Dos poylishe yidntum, see Jan Schwarz, Survivors and Exiles: Yiddish Culture After the Holocaust (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2015), 92-117. ↩

- About Bund in Sweden, see Håkan Blomqvist, Socialism på jiddisch: Judiska Arbeter Bund i Sverige (Stockholm: Carssons, 2020). ↩

- The book has appeared in Brazilian Portuguese translation: Ludwig Winograd, De Lodz a Buenos Aires: memórias do século 20, translated by José Tabacow (UFSC, 2016). ↩