For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

Introduction

In August 2016, I took part in the 10-day seminar “Documents on the Holocaust”, held by the Federal Archive in Berlin and the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI). This seminar as well as my participation in the Holocaust Summer Program in Kyiv between 1 and 12 July 2019, and the EHRI fellowships I held at the Centre for Holocaust Studies at the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich (November 2016, July – August and November – December 2017) facilitated my access to archival fonds in Germany and also to the latest European and American historical scholarship on the Holocaust. The available historiography does not by any means cover all the possible perspectives of research. One such aspect is the place and role of Soviet medical staff among the Jewish prisoners of war (PoWs) in the camps in Central Ukraine and beyond.

In this project I pay particular attention to the works by several other scholars. One of these is the fourth chapter, “The medicine of death”, of Aron Shpeer’s book “Captivity“. The chapter is based on the recollections of former Soviet PoWs, as well as on materials from the Yad Vashem archives.1 In addition, the findings of Pavel Polyan’s research on the card indexes of the Central Archive of Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation are highly pertinent.2 According to Polyan, during the war more than one third of officers-prisoners of war of Jewish origin, who died in various camps, were military physicians, veterinaries or medical assistants. About two thirds of them were born in Ukraine and almost 80% of them were captured in Ukraine in 1941, with 60% of them being captured in the month of September.

I assume that various sources are not used to their full limit, particularly sources such as testimonies, sound recordings, archival and photography collections, which can make this aspect of scholarly discourse much more diverse. The new information, especially in the digitised video interviews with Holocaust survivors, is of great importance because it can significantly assist historical research 3 and partially fill the lack of German documents about the fate of the Soviet PoWs, among them Jews and Jewish medical staff in German captivity.

This project focuses on the history of the medical staff within a comparative, transnational and interdisciplinary framework. The sources stem from my research in the Documents of the Central Office of the Land Judicial Authorities for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes (Federal Archives, Ludwigsburg – ZSt); the State Archive in Ludwigsburg (Starch. Ludw.); the Bavarian State Archives, Munich; the Archive of the Institute for Contemporary History, Munich (IfZ); video interviews from the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive (USC VHA), which are newly available also in Kyiv at the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Centrum; and the archival documents of the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, which are available on the website pamyat-naroda.ru. The new information, especially that contained in the digitised documents, led to the following questions: What was the policy of the Wehrmacht and SD (German Security Services) towards various groups of Jewish PoWs and medical staff in particular? What were the functions and opportunities of the medical staff of Jewish origin in camps for Soviet PoWs, taking into consideration their legal status as well as their changed identity? How can we define the role of the staff in the civil hospitals of towns and regions in the treatment and saving of Jewish PoWs? How could female medical staff help Soviet PoWs, especially Jewish ones?

The timeframe covered in this blog post is the whole period of the Ukrainian occupation, starting from 22 June 1941, up to retreat of the Wehrmacht in 1943/44.

The orders of Reinhard Heydrich and the Jewish medical staff in the camps of the Soviet PoWs

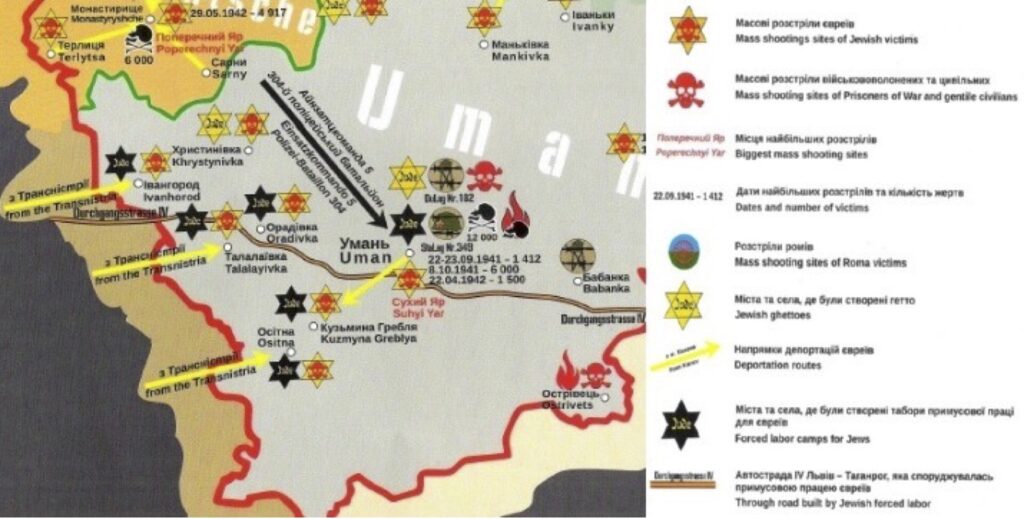

After Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers and officers became PoWs. During the course of military actions in Central Ukraine in the summer of 1941 there were two large encirclements by the German forces: Uman, with around 103,000 Red Army soldiers and officers; and Lokhvica, with 665,000. By September 1941 seven Stalags (PoW camps) had been established on the occupied territory of Ukraine: in Rovno (in Ukrainian Rivne), Kovel, Proskurov (Proskuriv), Shepetovka (Schepetivka), Vinnitsa, Zhitomir, and one Oflager in Vladimir-Volynski (Volodymyr-Volynsʼki). Upon the further advancement of the Wehrmacht into northern and Central Ukraine four additional Stalags were organised: in Belaia Tserkov (Bila Tserkva); Kiev (Kyiiv); in Bobrinskaia railway station (today named Taras Shevchenko station, in the city of Smela); and in Uman. In November 1941, under the control of the Chief Commander of RKU, Karl Kitzinger, there were 14 Stalags. The Stalag in Kremenchug was subordinated to the Commander of the Army Group South.4

Mapping this document was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin), the historical borders used here were adapted from the Spatial History Project.

Notwithstanding the unconditional and uncompromising anti-Semitism and Judeophobia of the National Socialists, who started the mass extermination of the Jewish civilian population and of the PoWs of Jewish descent from the first days of the invasion of the Soviet Union, their attitude towards Jewish doctors was not so unambiguous.

The orders of the Nazi authorities regarding use of Soviet medical staff, including Jews, are little known. Such orders were issued by Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the German police and Security Service. The first one was signed on 2 July 1941, i.e. ten days after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union: “Special attention should be given to the execution of doctors and other medical personnel. As the country has only one doctor per 10,000 inhabitants, due to the prosecution of a multitude of doctors in case of epidemics a vacuum that cannot be filled may emerge. If in individual cases the execution is necessary, it can be carried out, but only after a thorough check”.5

We can assume that occupational authorities quickly realised that the lack of medical staff was much more severe than what they initially thought. So they decided not to kill doctors and sanitary personnel among Jewish PoWs and engaged them in work. The second order was issued on 29 October 1941: “Jewish doctors and Jewish sanitary personnel are not subject to executions”.6 Very often, Jewish doctors were also used as interpreters. The pragmatism of the Nazi leadership is obvious in this period of successful offensive operations in the Soviet Union. But in 1943, after the crushing defeat of the Wehrmacht at Stalingrad and in the wake of the counter-offensive of the Red Army, the Security Service (SD) resumed the practice of exterminating all Jews, including doctors.

Based on my research in different archives, in this blog post I present some information on several German camps in Central Ukraine. As is widely known, from the period of 1941 to the first half of 1942 conditions in the camps were awful – with hunger, unsanitary conditions and various diseases being widespread. But soon it became clear to the Germans that they needed Soviet prisoners as a labour force not only in Ukraine, but also in Germany. This need somewhat influenced the German policy towards PoWs, as medical care became one of the critical issues in captivity.

It was provided to the PoWs by so-called “Russian Doctors”, i.e. doctors from the Red Army, irrespective of their ethnic origin.7 But PoW doctors could provide assistance to the wounded only in the most basic of ways. Michail Pronman, who was in a camp near Khmelnitsky in the winter of 1941-1942 recalled that his abscess was cut with an ordinary knife.8 As a rule, in 1941 in all containment and transit camps and Dulags for Soviet PoWs organised medical care was not properly provided. Most likely it was provided as an act of human solidarity. Shifra Golʼdbaum, born in 1919, who was taken at the end of September 1941 to the camp in the village of Dolgovo and fell seriously ill there, was placed in a barrack where PoW medical staff were held. They managed to hide her. “If the Germans found me, I would have been shot […]. When I came to consciousness, I was given half a glass of water and a small piece of bread. I will never forget that.”9

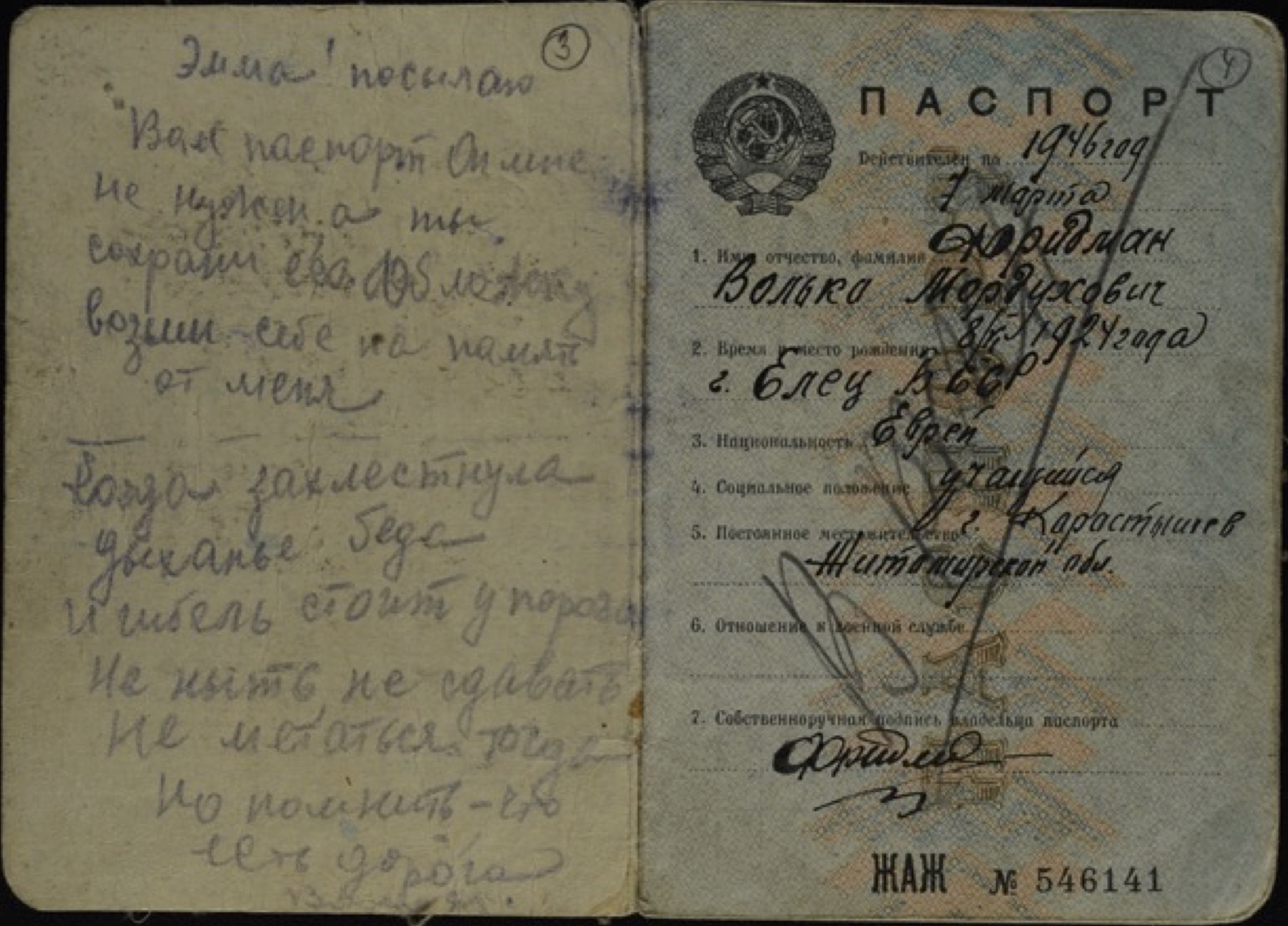

After the Stalags were established in the autumn of 1941, some barracks were organised into hospitals and barracks for the medical staff (Fig. 1). Jewish medical staff were not prosecuted the same way as other Jews were, moreover, they received better food rations than other POWs. Stalag 345b was at Bobrinskaya station in Smela. In 1942 the Stalag was converted into a large infirmary for PoWs with a small labour camp located nearby. The main camp had about 5,000-10,000 PoWs, the infirmary around 200-300 and the camp for Jews 100-200 PoWs.10

There were cases when Soviet doctors took care of German soldiers, who were ill with typhoid. Some witnesses during the post-war investigations recalled the high professionalism of a Jewish doctor named Bildstein. Allegedly the Germans, saved by this doctor, appealed to the Army Commander for his salvation.11 This may have been Blitstein Michail Solomonowitsch, who is mentioned on the website pamyat-naroda.ru as a military doctor of the third rank. He was drafted into the Red Army in Kiev in 1941 and subsequently went missing.

A Jewish soldier, Abram Pogrebetskii, after being wounded, was taken to the Stalag in Smela in 1943. He was in an overcrowded barrack for the wounded, from where paramedics took him to be bandaged by doctors from Poland. Pogrebitskii was rather afraid to be among the Poles, but because his wound started to putrefy, other PoWs called the paramedics, who then took him to the doctors. They undressed him and, having found that he was a Jew, immediately called a commander and another German soldier. The latter started to beat him and Pogrebitskii, completely naked, lost consciousness. He came to consciousness already in the barrack and he saw that he was treated with a bandage and his wounds were dressed. One camp policeman, who turned out to be a countryman of Pogrebitskii from Baky, confirmed that Pogrebitskii was an Azerbaijani. Later on, he was treated by a doctor from among the PoWs in his barrack. This episode confirms that by 1943 there were no Jewish doctors anymore in the hospital of the Smela Stalag.

Dulag 205 in Darnitsa functioned from 25 September 1941 until the end of October of the same year. It was later replaced by Stalag 339. Both camps, as well as all others, followed the Nazi policy towards PoWs and the selection and the prosecution of the so-called “unacceptable PoWs”, i.e. Jews and political commissars, was carried out.12

In the summer of 1941, female Jewish doctors and nurses were taken to the camp. One of them, Valentina Krivitskaia, recounted in a video interview, that after being taken as a PoW, together with Red Army soldiers, the nurses themselves had to pull carts with the wounded PoWs. In the camp they were placed inside a church. Due to the absence of medical care many of the wounded prisoners died every day.13

Sarra Erlikhman testified that wounded prisoners were also placed in a former pigsty: “One small table was put there for a doctor. Doctor Sych Zinaida gave [the wounded] some iodine and spirit […]. Once a day they were given unpeeled cooked potatoes.”14 These nurses, including Klara Kovalenker, mentioned by Krivitskaia, managed to leave the camp on 3 October, supposedly with their identities changed to those of local residents.

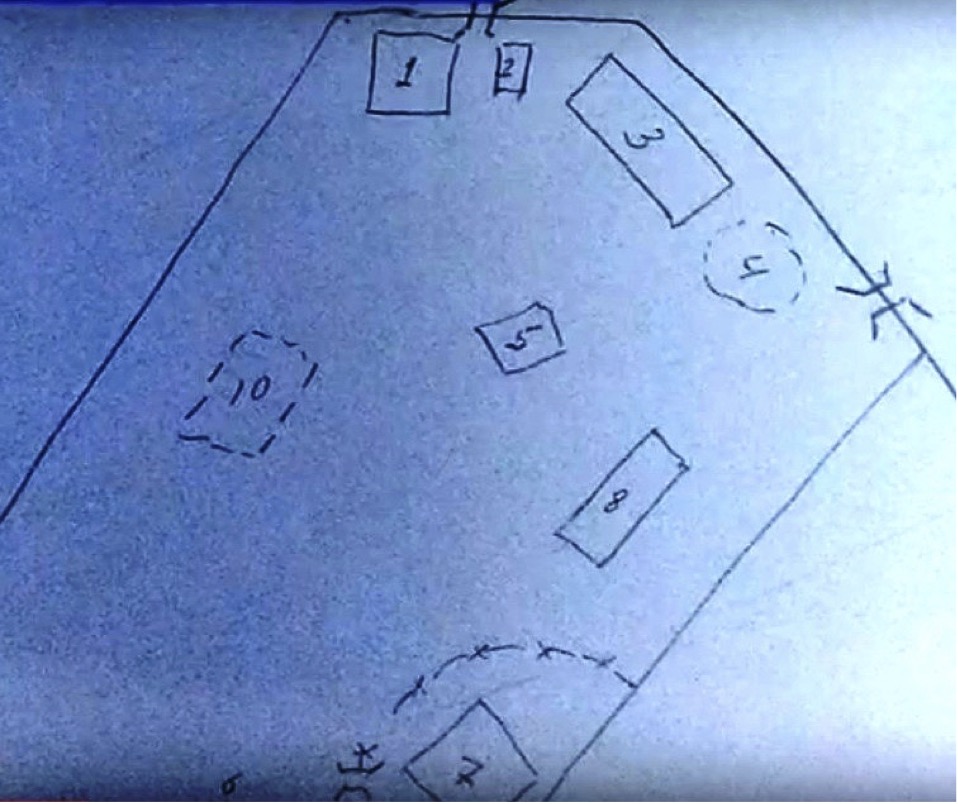

In Stalag 349 in Uman a hospital was organised for the wounded PoWs.

Efim Kaplan, a young Jewish soldier was sent here as well. According to him, there were seven or eight barracks, each for 100 people. All personnel were PoWs. The video interview with Efim Kaplan gives us information about the destinies of three Jewish doctors: Bondar, Vernik and Vovchek. The Jewish doctors saved the young soldier’s life, giving him part of their food rations, which were a bit better than those given to the rest of the PoWs. Risking their own lives, they hid his Jewish origin.15 “No registration. Jews were not rated high in captivity. Bondar and Vovchek were doctors and Kaplan was their assistant. I started to swell from protein starvation, was laid down on a plank bed, inspected and was found to be a Jew. The doctors were given better food from the kitchen than the others. One pot they eat by themselves, the second was given to me. Both were Jews. The Germans kept these Jews up until evacuation and then started to execute them. Vovchek and Bondar were shot at the airfield. We were told about it by one policeman, in the summer of 1943, when we were supposed to be transported further to the West. Vernik was not shot, as he slit his wrist and for some reason, they were not accustomed to killing a man twice. Kurzvei, who was the head doctor and the interpreter at the same time, simply poisoned himself […] Schmidt also slit his wrist, lost a lot of blood. One time there was a check for Jews before dispatch to the West – a German colonel-doctor ordered me to undress completely naked and to demonstrate ‘the instrument’.”

This interview shows the selflessness of Jewish doctors, who saved Efim Kaplan, and their own tragic fate. They knew that the Nazis would kill them anyway, but they did not want to be killed. In such cases suicide was a type of protest; they did not want to be victims and have chosen the utmost courageous option. We know that the overall number of doctors of Jewish origin, who were in the service of the Red (later Soviet) Army and died during warfare, was approximately 6,000. How many of the Jewish medical staff died in camps for PoWs is an open question. Out of the six names mentioned by Kaplan in the interview, only one was identified on pamyat-naroda.ru, the military physician of the second rank Abram Vovchik. He was a surgeon of the 373rd Detached Medical and Sanitary Battalion of the 117th Infantry Division. In the order of the Main Military-Sanitary Department of the Red Army Vovchik is mentioned as missing in action on 15 December 1941.16

We can clarify some of the data on the Stalag in Uman from the 1965 investigation files kept in the Federal Archives in Ludwigsburg. According to the testimonies of Adam A., a hospital assistant, the main camp was situated in the barracks of the Russian cavalry and the section for the ill PoWs was in the former riding hall, which was separated from the rest of the camp by a barbed wire fence. Here patients with no serious diseases were kept, around 600-700 men. The hospital for seriously ill patients was in the premises of the former kolkhoz, approximately 2 km from the main camp.

The camp was liquidated on 4 November 1943, its prisoners (around 20,000 people) were transported to Germany and Czechoslovakia. Among them was Mikhail Shkol’nik, who testified that the wounded were treated in 1943. In the case when a PoW could not do a job, a doctor was called in to assess his health.17

According to the testimonies of Hans C., a member of the administrative staff at the Stalag was making lists of Jewish PoWs among the doctors, interpreters and medical personnel for their dispatch to the officers’ camp in Vinnitsa already in April 1943. As we now know, three of the Jewish doctors committed suicide, the rest were shot. Similar episodes took place in Stalag 346 in Kremenchug, as confirmed by documents from the investigative files in Ludwigsburg. As one German serviceman of the Stalag commando testified, Abwehr officers beat Jews to death, although many Jewish doctors survived. Twenty doctors and assistants took care of the patients with typhoid, about 200 of them in total. The barrack for infectious diseases was in the rear area of the camp, across the road to Kremenchug. It was surrounded by barbed wire fence. As the headquarters doctor, Gotthold R., admitted: “the medical staff from the prisoners of war had very good knowledge”.18 Nevertheless, the fact of the brutal attitude of the German doctors towards Jewish doctors is well known. For example, in January 1942 a German doctor, who supervised the work of the doctor-prisoners, beat Professor Leonid Genis, a well-known specialist in ophthalmology, who had studied in Germany and was working as an interpreter in the Stalag.19 In the spring of 1942 a group of Jewish medical staff, including men and women, was prosecuted by the order of the camp’s commandant, Leple. He justified his order in the following way: “We are not the first in this action, sooner or later they will be shot. So it is better to shoot them right now”.20 He thus disregarded Heydrich’s order long before the Red Army offensive.

The Jewish personnel also removed the dead from the camp. Outside they were met by other Jews, who stacked the corpses and covered them with soil and chlorine. The exterminations of Jews and commissars were regularly carried out by SD groups, comprising of 3–4 officers and 4 junior officers or soldiers. Most likely, they were servicemen of the so-called Karl Julius Platt unit, which was a subordinate of the Representative of the Commander of the Security Police and Security Service and Commander of Army Rear Region В. A unit of 30-40 people operated together with the Second Company of the Third Police Reserve Battalion. (Platt, who headed this service in Kremenchug, died in action on 27 August 1943 near Lutsk – O.R.). One of the stalag personnel saw from the window of his office how this unit shot 30–40 Jewish men and women from the medical staff (according to other testimonies there were about 20 people – O.R.) in April 1942.21 According to the files of the investigation in the Archive of Contemporary History in Munich, the order for the shooting, which contradicted Heydrich’s order mentioned above, was given by a senior lieutenant named Betz, the commander of the First Branch of the Second Company of the Third Police Reserve Battalion. He personally ordered the shooting.22 A witness for this case, Johannes K., observed that there were two women among the executed: a woman aged around 50 and another between the ages of 18 and 20. The shooting took place in the anti-tank ditch near the infirmary.23 Some former German doctors of the Stalag claimed that Professor Genis was released from the Stalag in the summer of 1942, although others stated that they saw that he was also shot. Most likely this action took place as punishment for an attempted escape of several PoWs from the Jewish medical staff. The first group of prisoners forced to undress and lie face down; the other group was waiting apathetically, observing the shooting in the immediate vicinity.24 A young, elegantly dressed SD officer, with a stick in his hands commanded the shootings.

According to the testimonies of one of the former German doctors at the Stalag, Dr F., SD officers also took doctors and patients to be shot even as they were in the operating room, as well as some other people who were not mentioned in the preliminary list. Dr F. claimed that he managed to save a Jewish doctor named Kutz, because on his advice the doctor pretended to be a Tatar. His attempts to save Dr Simon Goldberg, a pathologist, were in vain, as everybody who was circumcised was shot.25 Thus, the use of Jewish medical staff was a temporal measure. Only escaping from a PoW camp could save someone from the unavoidable extermination. In such hopeless situations many Jewish doctors committed suicide. There are oral history testimonies that state that in the transit camps for PoWs the camp police out of collaborates and local auxiliary police were not instructed on how to deal with PoW Jewish doctors. According to Iakov Finkelberg, who was captured near Cherkasy, on the premises of a school at night where the PoWs were rounded up, drunken local policemen showed up and demanded that all Jews should come out. “One doctor came out as well as several assistants. They were beaten for an hour […] and maimed, but not shot. The policemen said that now these people are the property of Germans.”26

Women medical staff and Jewish PoWs beyond the camps

Soviet PoWs, including Jews under false identification, could count on the assistance in local towns and regional hospitals, where PoW doctors were also working. As mentioned above, Pronman who managed to leave the camp in exchange for a golden watch, was treated in the hospital at Proskurov (now Khmelnitsky) for 2.5 months, though he stayed there under a Ukrainian surname.

Iakov Talis, who escaped from the Dulag in Uman, was recognised in Gaissin by Dariia Leventsova, the wife of one of his subordinates, who was a doctor. Before the war Talis had helped her husband in a very difficult situation. She took Talis home, treated his wounds for three weeks and arranged for a false identity card for him.27

Moisei Revzon, a senior lieutenant in the medical services, was captured near Voronezh. Initially he was in Dulag 191 but later on he was moved to Poltava, where he worked as a doctor together with another Jewish doctor, Ivan Kasperovich.28 After Poltava he was transferred to the Stalag in Smela, from where he escaped with the help of women from the local underground resistance and joined the partisan unit under the commandment of Petro Dubovy (1911-1969) in the vicinity of Cherkasy.

PoWs from the Stalag in Bila Tserkva were also treated in the town hospital. Fedora Rigas, born in 1918, who worked there as a nurse recounted: “Prisoners of war were brought to us. They were tormented, dirty and hungry, with a high temperature. Among them were doctors, colonels, lieutenant colonels. Of all nationalities. Ukrainians, Jews, Georgians, Armenians. We washed and shaved them, placed them in hospital rooms […] The patients were brought by Germans on trucks. Doctors Geim and Resch came to us and inspected the PoWs. We were afraid. While going to work, you were thinking that someone could have denounced that we were hiding Jews, letting them out through the back doors […] One Jew – Grigoriy Suponitsky – was very severely wounded at the end of August 1941. Later he worked as a janitor at the hospital […]. We felt sorry for them, we wept over them, as they were brought to as in such a feeble state.”29

The Chief Doctor of the hospital, Slavinskiy, knew that there was an underground organisation in the hospital, which helped PoWs leave the hospital with the claim that they were unable to work. Previously, he had commanded a sanitary train of the Red Army but had to surrender in Borispol, when the town was taken by the Wehrmacht. According to Rigas, he pitied everyone and arranged for additional food rations for the hospital workers. After the Red Army liberated Bila Tserkva, he was arrested and sent to a forced labour camp in Donbas.30

The limitation of documents and oral testimonies does not allow us to estimate the scale of such assistance to Jewish PoWs, but mentioned facts demonstrate that it was possible and very often women were the rescuers.

Conclusion

The archival documents and oral history interviews I have reviewed here reflect the policy of the Nazi occupants of Ukraine towards Jewish medical staff, beginning in the autumn of 1941 up to the summer of 1943, when the Wehrmacht troops began to retreat under pressure from the Red Army. The pragmatism of Nazi officers for a certain period prevailed over their Judeophobia. But this deviation from their racist doctrine was short-lived, as was the use of a Jewish labour force for the construction of the DG ІV highway, which was supposed to connect Germany with the Caucasus. As soon as the works were completed, the Jews were subject to immediate extermination.31 Therefore, the same method of killing, as Father Patrick Desbois called it “Holocaust by bullets”, was applied to different groups of Jewish victims in Ukraine.

Second, there is no doubt that the role of the medical staff with Jews among them in the Stalags was very important. They saved many PoWs, when and if they had the necessary medications. They also treated German soldiers and officers, who later on tried to rescue these doctors. But the documents in the archives in Germany show, that there were many anti-Semitic German doctors, whose behaviour was not at all humane.

Thirdly, thanks to the female staff in civil hospitals in the towns and regions, some Jews under false identity, were treated and saved. These women, no doubt, risked their own lives. Their main motive was an ardent desire to help all the prisoners, whom they treated as “theirs”. In some cases help was provided to Jews, that the female doctors knew personally before the war.

In such circumstances medical assistance from the female staff was not the only important help, but they also arranged for new documents. Without such documents Jews could be immediately arrested and prosecuted by the Nazis.

On the title of the post see: Olga Radchenko, “Medyčnyi personal evreis’kogo pokhodzhennia v shtalagakh dlia radians’kykh viis’kovopolonenykh v Umani ta Kremenčuzi” (Jewish Medical Staff in Stalags for Soviet Prisoners of War in Uman’ and Kremenčug], Mizh Bugom i Dniprom. Naukovo-kraeznavčii visnyk Tsentral’noi Ukrainy. Kropivnitskii, 2020, 13, p. 114-118. It should be noted that this blog post is related to my findings which I presented in this article, but here I also added some new aspects.

- Aron Shpeer, Plen (Сaptivity), Mosty kultury / Gesharim, 2005, Vol. I, II. ↩

- Pavel Polyan, “Sovetskie voennoplennye: skol’ko ich bylo I skol’ko vernulos’?” (Soviet prisoners of war: how many were there and how many returned home?), Demografičeskoe obozrenie. 2016, Vol. 3, no. 2, p. 43-68. ↩

- Crispin Brooks. “Visual History Archive Interviews on the Holocaust in Ukraine”. The Holocaust in Ukraine. New Sources and Perspectives. Conference Presentations. Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, USHMM, 2013, p. 17-62. In Ukraine alone, the USC Shoah Foundation conducted more than 3,400 interviews over four years, 1995–1999. ↩

- Pastushenko Tetiana, Vijs’kovyi polon na terytorii RKU za materialamy zvitiv kerivnyka Vermakhtu v Ukraini 1941–1943 rr., Storinky voennoi istorii Ukrainy, 2017, Vyp. 19, p. 172. URL: http://resource.history.org.ua/publ/Sviur_2017_19_15, S. 177. ↩

- IfZ, GW 03.12/11, Bl. 5. ↩

- Ibid., Bl. 10. ↩

- State Archiv Munich, 36856/1, Bl. 163, 174. ↩

- USC VHA, Michail Pronman, 32250, Segment 32. ↩

- USC VHA, Shifra Golʼdbaum, 34038, Segment 25. ↩

- Starch. Ludw., EL 317 III Nr. 910, Bl. 103. ↩

- Ibid., EL 317 III 673, Bl. 113. ↩

- Z. St., В 162/8436, Bl. 428, 454, 460, 533, 543, 596, 635; В 162/8437, Bl. 727. ↩

- USC VHA, 23335, Valentina Krivitskaia, Segment 39. ↩

- USC VHA, 23262, Sarra Erlikhman, Segment 78. ↩

- USC VHA, 43730, Efim Kaplan, Segment 80. ↩

- Central Archive of the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, Fund of historical information: 33, Inventory of historical information: 11458, File of historical information: 216. ↩

- USC VHA, 16912, Mikhail Shkol’nik, Segment 50. ↩

- IfZ, GW 03.12/ 11, p. 2. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- IfZ, GW 03.12/14, p. 4. ↩

- Ibid., Bl. 186. ↩

- IfZ, GW 03.12. Akte 14, Bl. 5. ↩

- Ibid., Akte 16, Bl. 12. ↩

- Ibid., Akte 10, Bl. 4. ↩

- Ibid., Akte 14, Bl. 4536. ↩

- USC VHA, 32135, Iakov Finkelberg, Segment 51. ↩

- USC VHA, 28825, Iakov Talis, Segment 57. ↩

- USC VHA, 49486, Moisei Revzon, Segment 38. ↩

- USC VHA, 40099, Fedora Rigas, Segment 60. ↩

- Ibid., Segments 80–82. ↩

- See: Andrej Angrick, Annihilation and Labor: Jews and Thoroughfare IV in Central Ukraine, in: Brandon, Ray/Lower, Wendy (ed.): The Shoah in Ukraine. History, Testimony, Memorialization, Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2008; George Henry Bennett, The Nazi, the painter, and the forgotten story of the SS road, London: Reaktion Books, 2012; Hermann Kaienburg, Jüdische Arbeitslager an der “Straße der SS”, Zeitschrift für Sozialgeschichte des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts, 1999, Heft 1/96, p. 13-39; Olga Radchenko, Jewish Forced Labour on Road Construction between Uman and Kirovograd 1942/43,Holocaust and Modernity, Studies in Ukraine and the World, 2019, 1(17), p. 48-74. ↩