For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

Scraps of Paper

Among the innumerous sources to be found in the Yad Vashem Archives (YVA) are a great many personal collections of Jews from the Soviet Union. Most of them spent World War II in the Soviet rear or in the ranks of the Red Army, a minority survived the Holocaust under German or Romanian occupation. Some of them left behind testimonies, oral or written, others letters or diaries—but in fact, a lot of these collections contain nothing more than a handful of personal documents: passports, military IDs, diplomas, marriage certificates, death notifications, and all sorts of references and notes.

These kinds of sources do not usually receive much scholarly attention. Taken separately, they are rather fragmentary and offer only a glimpse of individual biographies. At best, historians use them in addition to more extensive narrative sources such as testimonies or correspondences, given these are available. Yet when you take a step back, it becomes apparent that, all taken together, these personal documents reveal a lot about how the Soviet system functioned during World War II. And how Soviet citizens navigated their way through it.

In this blog post, I take a closer look at the role these “scraps of paper” played in the Soviet Union during and directly after the war.1 I focus on the bureaucratic baggage of Jews from the Ukrainian SSR, with an emphasis on the city of Zhytomyr (the subject of my PhD research). This group of people suffered diverse fates during the war, but the survivors all had in common the experience of displacement. Whether they survived by hiding in a nearby village or were dispersed across the Eurasian continent, they found themselves wrested from their homes and daily lives.

I argue that the war put enormous pressure on Soviet bureaucracy, as the regime sought ways to keep control over its subjects at a time when millions were on the move. Soviet citizens, on their part, continuously faced the challenge of proving who they were and what they were entitled to under Soviet law. This proved particularly exacting when they returned to their homes and tried to reclaim their prewar lives.

At the same time, the upheavals of war produced bureaucratic flaws and loopholes which Soviet citizens could use to negotiate their position in Soviet society, even to change their identity. In the face of soaring antisemitism on part of the Soviet state, this last option gained wide appeal for Jews—as I will show in the final section of this blog post.

Controlling Movement and Labor

After delivering its subjects from the oppressive tsarist state apparatus, the young Soviet regime soon moved to impose bureaucratic restraints of its own. In the course of the 1920s and 1930s, a series of new documents were introduced, culminating in the introduction, in 1933, of the domestic passport.2 This document, usually just called “passport” (since foreign passports was the privilege of a lucky few), was issued at the age of sixteen, based on someone’s birth certificate. It served to identify its carrier and control where they could settle. Well over half the pages were reserved for the propiska, or residential registration. Without a propiska people were not allowed to live somewhere, meaning they did not have access to work, education, medical treatment or postal services. Repeated violation of the propiska regime was punishable with incarceration in a “correction-labor camp”.3

Passports were used to control the movement and labor of subjects of the Soviet regime at a time of rapid industrialization.4 Places of particular significance, the so-called “regime cities”, were off-limits to suspect groups such as former convicts and exiles. Overcrowded urban centers could, at least in theory, be shielded from excessive labor migration. People were only allowed to move to a new city if they, or their close relatives, had a valid ground to do so (an employment agreement, for instance).5 A substantial part of the population—the peasants—did not receive passports and, as a result, were tied to their kolkhozes—a situation that would persist until 1974.6 As most Jews were city-dwellers, only a few of them were condemned to this category of second-grade citizenship.

The domestic passport formed the central link in a complex bureaucratic system, encompassing a wide range of other documents. Key documents in Soviet society were the Communist Party card (partiinyi bilet), the military ID (voennyi bilet) and the “labor booklet” (trudovaia knizhka)—which all recorded an individual’s cumulative experience (stazh). The lifeblood of the system were the so-called spravki, or “references”: single-purpose documents designed to convey a specific piece of information about an individual, for instance, whether they were eligible for a certain position or entitled to a pension. This category includes the plethora of travel documents which people needed for long-distance travel.

The primary function of these documents was to transmit information about the individual carrying them from one institution or official to another, so that they could be identified and treated properly. It was not easy to escape the tight grip of this system, because it was designed to form logical sequences.7 Without a birth certificate, one could not get a passport. Without a passport, one could not get a propiska. Without a propiska—no job. Without a job—no travel documents. At every stage of life, whether they were applying for a job or moving, people needed pass these checks.8

It was by no means a flawless system, as revealed by both individual testimonies and official reports. Soviet bureaucracy was cumbersome and prone to corruption.9 Yet for all its flaws, the system had crystalized by the end of the 1930s and would remain in place until the end of the Soviet Union.10 As we will see in the next section, the German invasion of the Soviet Union put immense pressure on the system, but it did not lead to any substantial changes. Rather, after initially loosening the reins, the Soviet bureaucracy responded to the challenges of war by expanding massively.

From Disarray to Expansion

The rapid German advance in the summer of 1941 left millions of people under occupation and scattered millions more across the territory of the Soviet Union. It took the Wehrmacht 17 days to cross the 300 kilometers to Zhytomyr. By the time the city was taken, more than half the population, and well over half of Jewish Zhytomyrians, were gone—drafted, evacuated or on the run.11

The great migration set in motion by the German invasion posed a dilemma to Soviet bureaucracy. Its compulsion to control the population was offset by the urgent need to facilitate the flight of as many people as possible—hands to hold rifles and keep the economy running. For the time being, the regime gave in and relinquished many of the checks on movement. People were drafted into the military without much screening and internally displaced persons (IPDs) were allowed to board evacuation trains without travel documents.12 When they arrived in the Soviet rear—often in faraway places like the Urals and Central Asia—they were put to work at kolkhozes and factories in a haphazard way.

A lot of people had lost their passports and other documents somewhere along the way, but this complication was brushed aside.13 In many cases they received a spravka from their kolkhoz or factory director, which then served as their ID document for the rest of the war.14 The regime did try to reinforce control by introducing new “expert inspectors” to search for false documents, but the system was not as all-embracing as it had been before the war—at least for the time being.15

When the German offensive ran aground in late 1941 and the Soviet leadership had time to catch their breath, they tried to get an overview of the situation. The Central Information Bureau was created, first in Moscow, but it was soon evacuated to Buguruslan, deep in the rear, where it would stay until the end of the war. The Central Information Bureau was tasked with collecting information about evacuees from local authorities, for which a new kind of document was created: the “evacuee card”. In February 1942, the Bureau launched a campaign to register refugees across the rear, but the operation faltered due to sloppiness of local authorities.16 Many evacuee cards showed spelling errors or calling names instead of official names (e.g. Grisha instead of Grigorii).17 The endeavor was further complicated by a second wave of evacuations when the Germans advanced into Volga Basin in 1942. In the end, only about 40 percent of the estimated 16.5 million refugees were registered.18

Things weren’t looking much better in the military. In the course of the war, millions of men and women were mobilized, and millions were captured or killed. The army command relayed the essential task of keeping an overview of losses to the Central Bureau for Registry of Losses.19 But the data provided by the innumerous military units were blotchy. For the field headquarters, combat was priority number one and drafting new recruits priority number two. Keeping track of fallen soldiers and officers only happened when circumstances allowed. As we will see below, people could desert from the army and re-enlist under a different name without anyone noticing.

The Soviet regime did, from the very start, invest great effort in screening individuals—both civilians and military—who had been under German control. The leadership harbored a deep mistrust towards these people, assuming they were spies and agents, and forced them to undergo a procedure dubbed “filtration” (filtratsiia). An early example of this is Gitlia Grips and her 5-year-old son Leonid. Having survived the mass shooting of Zhytomyr Jews on 19 September 1941, mother and child walked all across Ukraine for three months, to cross the lines into Soviet territory on 19 December. They were immediately handed over to the NKVD, separated, questioned and abused. When the officers finally decided their story was credible, Grips received a spravka that she had passed filtration and been released. She survived the war working for the military in Astrakhan and Saratov.20

This issue of filtering out unwanted “elements” became pressing during the rapid advance of the Red Army through Ukraine in 1943. To streamline the process, a new security organ was created: the SMERSH (short for Smert’ shpionam, or “Death to Spies”). When an area was “liberated”, the locals were forced to renew their passports and for this, they had to pass screening.21 Although the few surviving Jews were highly unlikely to have collaborated with the Germans, they were not exempt from this duty. On the contrary, the fact that they survived in itself was considered suspicious. Because the war machine remained the highest priority, men drafted into the army were screened less thoroughly—this was postponed until after they had fulfilled their duty.22

When Soviet forces moved into Poland and even further west into Germany, the filtration operation took on new proportions. An infrastructure of camps and transfer points was set up to “repatriate” Soviet subjects—forced laborers, POWs, and civilians who had fled the Red Army (the number of Jews in these groups was low, for obvious reasons, although there were some who had been able to hide their Jewish identity). After initial screening, women were sent back to their homes in the Soviet Union, whereas men were usually drafted into the army.23 After they had fulfilled their duty (in some cases they had to serve until the 1950s), they were screened again and either sent to labor battalions in industrial regions or also sent home.24

It appears there was an ingenious logic behind sending people home, although the question is if it was by design. If someone had collaborated during the occupation, they would most likely have done so in their home region. So by forcing people to return home, the regime increased the chances of them getting recognized and reported. It was the most reliable way to bring former collaborators to justice.25 On the eve of departure, repatriates and demobilized soldiers received a spravka saying they had to report to the authorities in their home towns. In contrast to the first months of the German-Soviet war, the railway system was once again under heavy surveillance, so traveling somewhere else was nearly impossible.26 If people did move to another city, they were condemned to a life in illegality—for lack of proper documentation.

At the same time, the regime was trying to prevent refugees in the rear from returning to Ukraine (and the other reconquered territories). The Soviet leadership was afraid it would not be able to control this movement and that the economy in the rear would collapse. For these reasons, “evacuees” were restricted from boarding trains to the West, unless they were in possession of a solicitation, i.e. an invitation from either an institution or enterprise, or from relatives. This obstacle was particularly difficult to overcome for Jews, since only a few of them had surviving family members in the newly-liberated areas. Although most would eventually return home, the obstructions slowed down this process so as not to overburden the bureaucratic checks.27

As the war came to an end, the regime regained nearly total bureaucratic control over society. It speaks to the efficacy of the system that it did not undergo significant changes during the war. The regime trusted the system of checks to do its work and expose people hiding their past—which it did, as we will see below. However, the war did leave its marks on the bureaucratic system in another sense. Soviet society was reordered based on wartime trajectories, with former soldiers on top of the pyramid, with privileged access to education, jobs and benefits.28 Correspondingly, those who had survived the German occupation or, even worse captivity, now faced restrictions of all kinds. They would bear this stain until the end of the Soviet Union—for it was written into a separate section of their domestic passports.29

At the same time, another, ethnic hierarchy emerged. In postwar Soviet Ukraine, Jews were collectively depicted as cowardly evacuees and subjected to discriminatory measures—such as restricted access to higher education.30 To enforce these measures, the passport did not have to be modified. The category of “nationality”, originally designed for purposes of affirmative action, had been part of the Soviet domestic passport since its conception.31

Caught up in the Gears

This summarizes the regime’s efforts to keep and regain bureaucratic control of the population during the upheavals of World War II. So how about the people caught up in this paperwork machinery? Apart from facing existential threats due to the war, they also faced the challenge of navigating Soviet bureaucracy. As I will show in this section, Soviet citizens pursued their own interests in dealing with the state, which in some cases matched those of the regime, but more often did not.

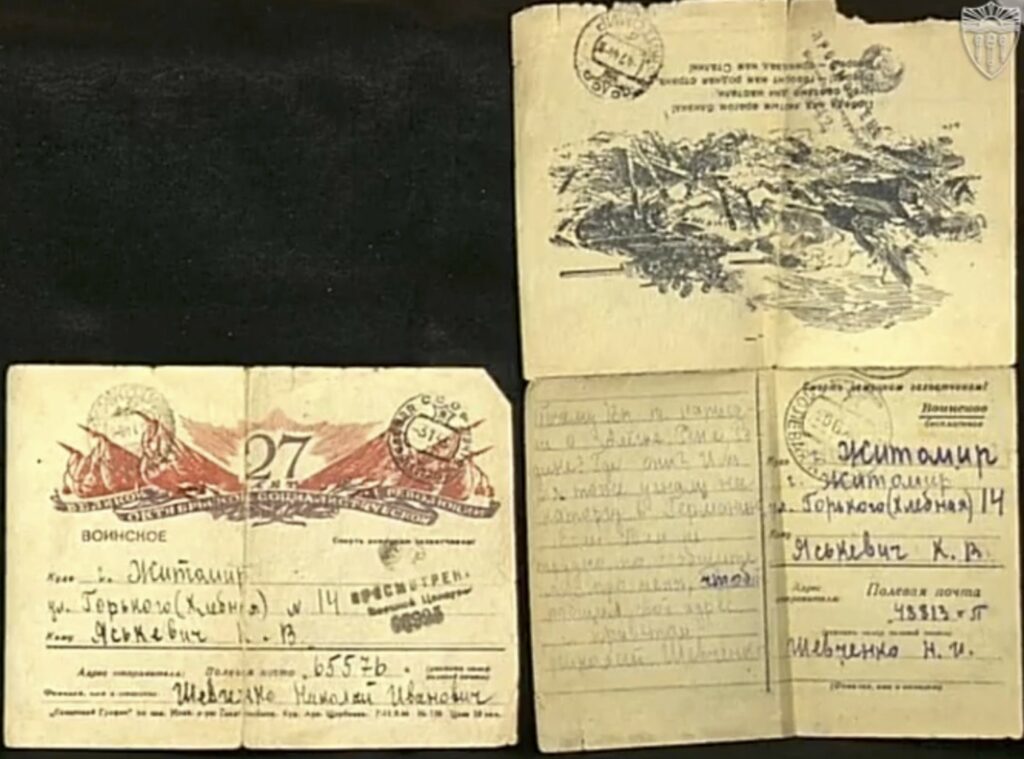

At any given time, the top priority for citizens, whether they were in the rear or the military, was to get in touch with relatives and find out who was alive.32 The regime facilitated these efforts with the Central Information Bureau, which served not only officials and institutions, but also processed individual requests from citizens.33 A word about the services of the Bureau spread, and soon people started flooding “Buguruslan” with requests.34 In the case of the military, there was no centralized office that people could turn to, making the quest to find out the whereabouts of relatives under arms nearly impossible. Field headquarters, conscription offices and local authorities all tried to inform people about relatives’ whereabouts, provided that information was available—but in many cases, it was not. It was no exception for Soviet citizens to reestablish contact with their loved ones only after the war.35

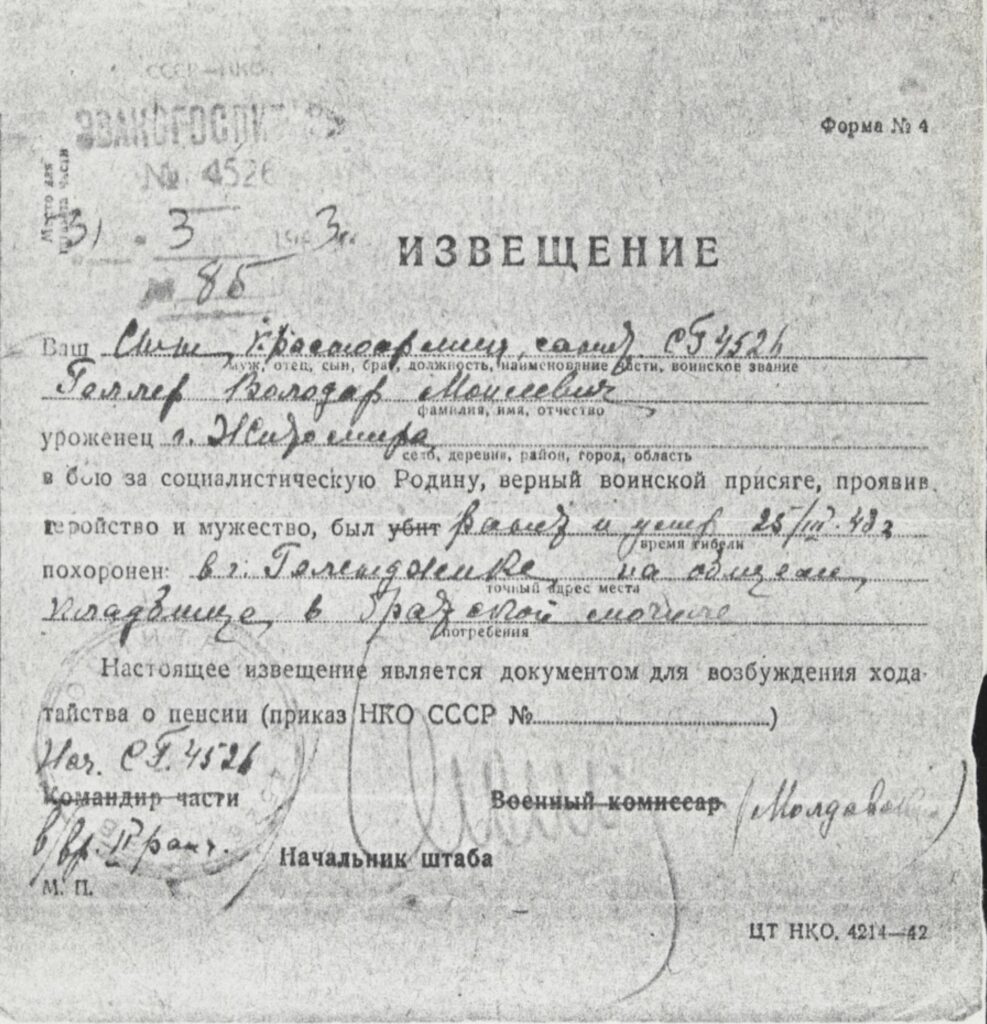

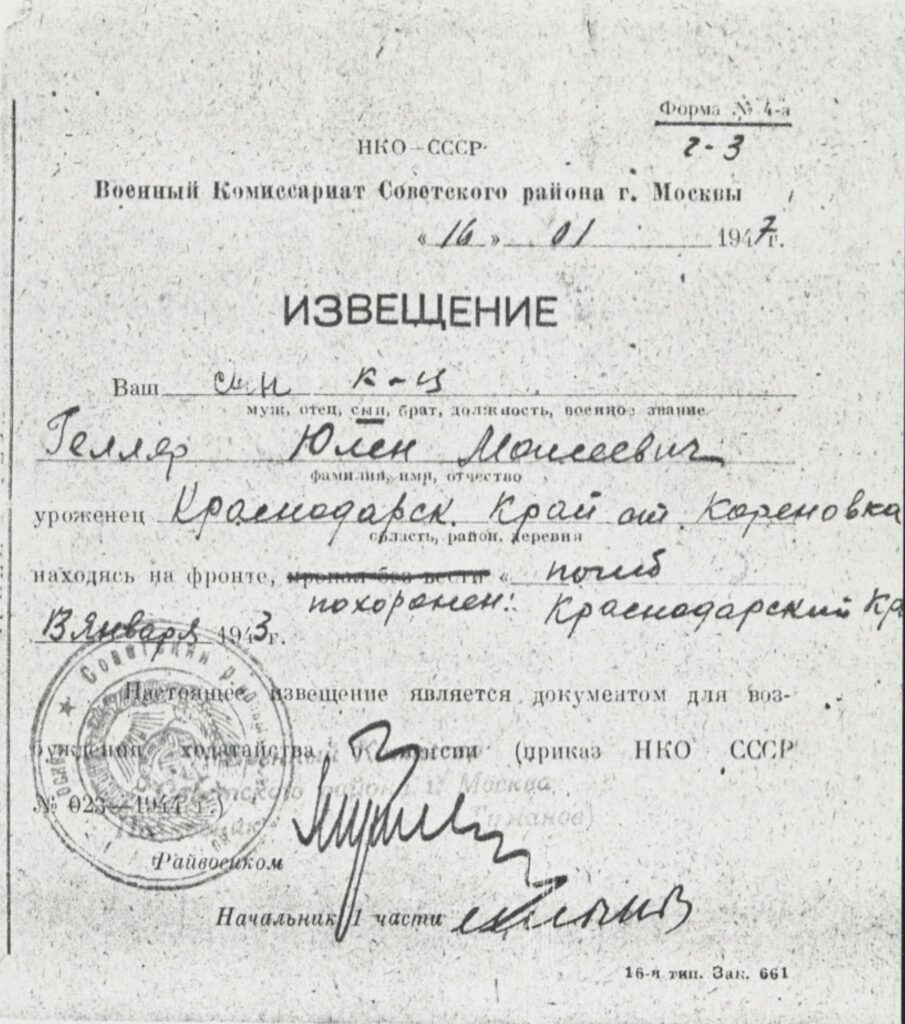

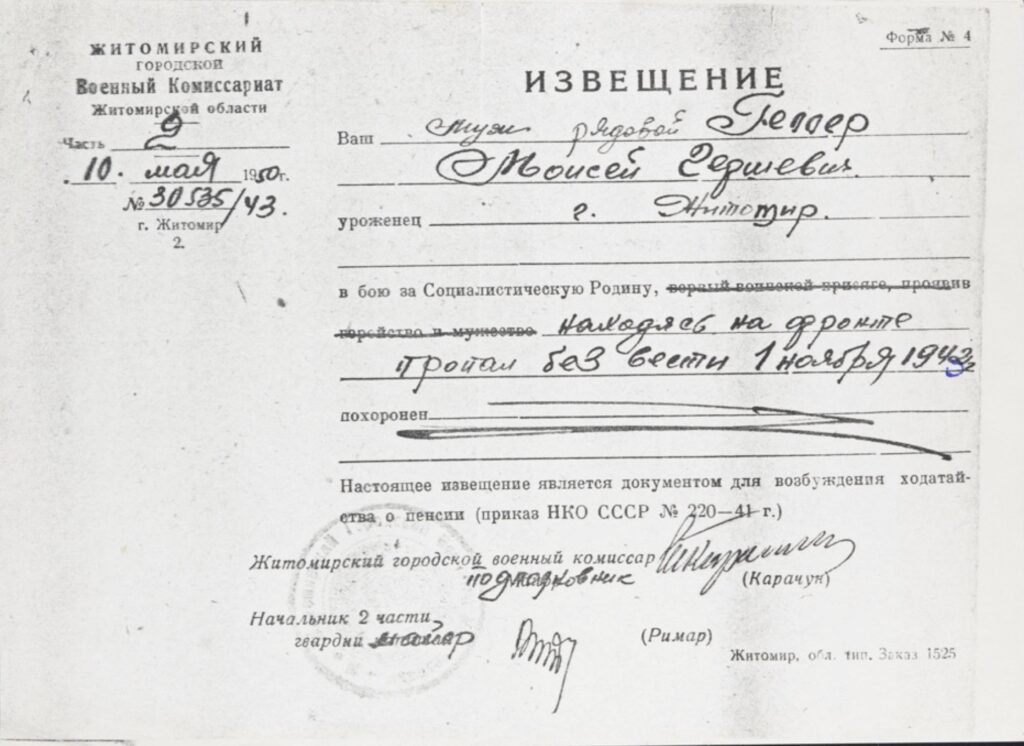

In case a relative had died, moreover, it could take years for this to be clarified. As the war progressed, field headquarters and hospitals invested increasing effort in reporting deaths to next of kin by means of “death notifications” (izveshchenie o smerti). Still, this was by no means a priority. Take the case of Tsipa Rudenberg, a fervently communist nurse from Zhytomyr, who evacuated to Baku with her husband and two adolescent sons, Iulen and Volodar. In September 1942, the entire family was mobilized, the men to fight on the front, Rudenberg to serve as a nurse. Contact with her husband was soon lost. Her older son died in combat in the foothills of the Caucasus in January 1943–his younger brother was nearby and was able to bury him. One month later, the younger son was injured in the abdomen and, by coincidence, ended up in Rudenberg’s hospital, where he died in her presence. She received a notification of the younger son’s death from the doctor in charge. Though she knew about her older son’s death, probably from her younger son, it would take until 1947 for her to get a confirmation of this from Moscow. Her husband’s fate remained unclear. He was never reported dead so in 1950, the Zhytomyr conscription office declared him “missing in action” (propal bez vesti). Rudenberg herself would serve until 1948 and rise to the rank of lieutenant.36

After the war, Soviet officials did try to compile overviews of total losses. However, they did not go about this systematically, nor did they try to account for all missing men and women. Instead, they acted reactively, only looking into the fate of a soldier or officer when their relatives filed a request. Whenever someone’s death could not be confirmed, they were filed as missing in action. The whole process was handled in a mechanical way. So when Mara Gimelfarb, in 1944, reported her father Itsko had not written her since July 1941, the Ministry of Defense simply replied that he had gone missing in September 1941, two months later. Itsko Gimelfarb was added to a list of 100 soldiers and sergeants who were all filed as having gone missing two months after they had last been in touch with relatives.37

Around the same time, Gimelfarb found out her brother had been killed at the front in February 1944. His unit had sent the family a notification but by the time it reached their evacuation address in Saratov Oblast, they were on their way back to Ukraine.38 In this specific case, the family would have found out about their relative’s death faster if they had stayed in the rear. The opposite was more likely to occur, however. Most refugees tried to return home because they rightly reasoned this would increase their chances of getting in touch with surviving relatives and finding out about the fates of those who did not make it.

For this reason, people started returning to Ukraine as early as late-1943—against the will of the regime, which sought to slow down this process as much as possible. Still, refugees found ways to circumvent the restrictions on travel. Raisa Zubataia from Uman was so fortunate that her husband’s army unit passed through their home town and he was able to arrange the necessary documents for her: a direction (napravlenie) to Uman and a separate document covering the expenses. Once people had arrived home, they would usually help their relatives by sending them solicitations, creating a snowball effect.39

Returning home was much easier for people who had survived the occupation or had been deported to west as POWs or forced laborers. As said, there might have a rationale for the regime to force them to return, because that made it easier to expose their wartime exploits.40 In any case, those who had reasons to lay low might try to disappear, for instance to the Donbas, where hands were needed and not many questions were asked.41

The opposite could also happen. Some men were sent to industrial regions to work in labor battalions against their own will. Igor Kharpatin, a young Jewish man from Zhytomyr, survived the German occupation and was liberated in Germany in 1945. He served in the Red Army for two years, before being sent home together with a group of other former POWs—or at least that was what they were told. When they reached the Soviet border, it became clear they were being transported to a labor battalion. Kharpatin decided to make a run for it and bribed his way to Kyiv, where he settled down. He was able to go off the radar, but the price was high: without papers, he could not get a proper flat or job.42 People like Kharpatin were doomed to an existence in the margin.

Still, in the great postwar sorting, even people with clean records faced the challenge of proving who they were and what they were entitled to.43 In many cases, people had lost their passports and had been using wartime spravki to identify themselves. To receive a new passport, they had to return to their home towns to retrieve the copies of their birth certificates, kept either at the local civil registration office (ZAGS) or at an archive. The birth certificate could then be used to apply for a new passport at the police.44 In some cases, however, the local archives had burned down or otherwise been destroyed. In that case, people needed any documentation they could lay hands on, plus testimonies from acquaintances, to confirm their identity and receive new papers.45

The next challenge was to retrieve credential documents. Citizens needed to return to their former schools to obtain new diplomas or get in touch with former employers to receive new labor booklets.46 Wartime spravki became credential documents in their own right.47 Those who had served in the army would be carrying loads of spravki from all the positions where they had served, to prove they had seen active service. This was more difficult for former partisans, who often did not receive any spravki and struggled to substantiate their wartime accomplishments.48

Similar problems were experienced by many refugees who had worked at kolkhozes or factories in the rear. Since administration tended to be patchy, they often did not possess spravki to account for all the work they had done during their time in evacuation. For example, in 1965, Grigorii Liberman from Zhytomyr got in touch with the Kurgan Agriculture Machines Factory, where he had worked during the war. He needed a spravka to have his labor stazh updated, so he could received the pension he was entitled to. But they spravka the factory sent him only confirmed part of the time he had worked there.49 People who had survived occupation were even worse off, they would not be compensated for missed worked experience—yet another way in which they were discriminated against.

Then there was the issue of registering dead or missing relatives. This was not only necessary for emotional closure, it was often a bureaucratic prerequisite to continue one’s life.50 Mariia Cherkasskaia, a teenage girl from Zhytomyr who escaped the local ghetto and survived the war by hiding in the countryside, had to get a spravka about her parents getting shot by the Germans to enrol at an evening school.51 For the relatives of soldiers and officers who had not returned, it was important to obtain proof that the latter had died in combat or succumbed to injuries because this entitled their families to allowances (pensii) from the state. As explained above, the burden of clarifying deaths and disappearances lay on the shoulders of the bereaved. In many cases, people simply vanished without a trace.52

Thus, Soviet bureaucracy generally helped citizens get and stay in touch with relatives but hindered them in other ways. It forced repatriates to return home and delayed refugees in their efforts to do so. It required people to invest large efforts to reclaim their prewar lives and claim entitlements based on their wartime experiences. Yet the war and the postwar period also created loopholes for people to exploit and to negotiate their position in Soviet society—as I will discuss in the final section of this blog post.

Flaws and Loopholes

It has been claimed before that, in the course of the war, a hierarchy emerged based not on class but on wartime conduct—with former military on top and occupation-survivors in the bottom. Privileges were divided by the regime based on this hierarchy, with military and their relatives having easier access to travel documents and allowances. Occupation survivors, on the other hand, were suspect by definition and would often struggle to get access to jobs or education.53 At the same time, another hierarchy emerged, based on ethnic background. An upsurge of antisemitism barred Jews from receiving prestigious education and high positions.54 However, this discrimination could be overruled by immaculate wartime background.55

Quite understandably, these divisions of privileges compelled people to cheat and circumvent the system. And as these hierarchies were enforced using bureaucratic means, often those very same scraps of paper, there were many ways to do so. This often involved adjustment, change or multiplication of one’s file-self—the version, or multiplicity of versions, of a person existing in documents.56

The most obvious case was that of outright scamming. Take the case of Veniamin Vaisman, a Jewish man from Zhytomyr who survived the war in the rear. When he returned to postwar Kyiv, he started presenting himself as a lauded war veteran, claiming all sorts of benefits for himself. His deceit was so blatant, local officials reported about it to Moscow when Vaisman was finally exposed and trialed.57

Other people used the upheavals of war to hide past misconduct. Take Fedor Travkin, a Russian from the Smolensk region who had made a nice career for himself in the Communist Party prewar, until he was suspended in 1939 for “political negligence” as head of an aeroclub in Kirov. During the war, he worked various jobs in infrastructure in the rear, before moving to newly-reconquered Korosten, Zhytomyr Oblast, in 1944. Hands were short and local officials were desperate to fill positions. Travkin had an impressive stazh and, crucially, lied about his suspension from Party. He was appointed director of quarry and occupied high Party position. It would take until 1948 for him to get caught and expelled from the Party again.58

There were ways of making use of war-related loopholes that were less overtly mischievous. These involved changing one’s name and ethnicity (changing age was also widespread, especially among draft dodgers, but space does not allow for a discussion59). This kind of evasion appears to have been particularly prevalent among Jews, for whom appearing to be less Jewish became a desirable end during the war.60 In the Jewish case, this was also grounded in a long tradition of “passing” and using a different name outside of the community.

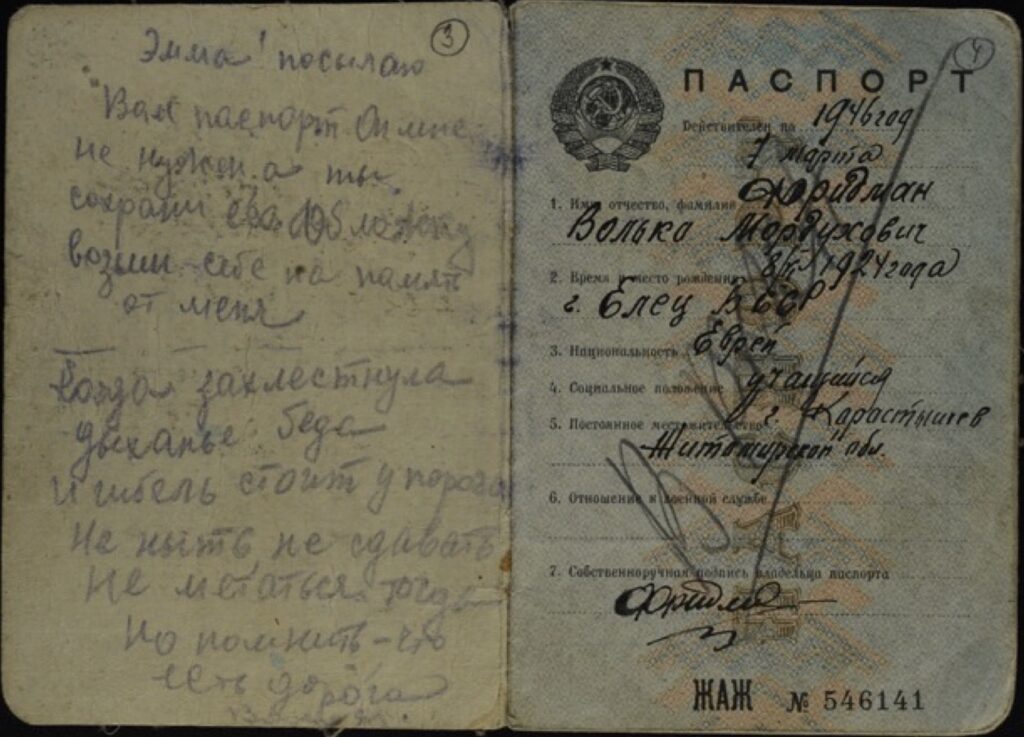

Gitlia Meerovna Gimelfarb started calling herself Genia Markovna during the war, in evacuation at a kolkhoz in Saratov Oblast. Her daughter Mara started calling herself Mariia. Both used these new names in official correspondence—which must have been a conscious decision when they registered at the place of evacuation. Gitlia/Genia reverted to using her Jewish name after returning to Zhytomyr in 1944, perhaps because she received a new passport based on her birth certificate.61 Or take Gersh Raitsin, who was mobilized into the military from evacuation in Stalingrad Oblast in 1942 and got first registered with his Jewish birth name, only to change it consistently into Grigorii from then on. He was apparently able to keep his “Russified” name after the end of the war.62

Changing one’s name was relatively easy, it was more challeging to switch ethnicity—though the war offered windows of opportunity here too. A good example is Arthur Sukiennik, born Aron, a Polish Jew who ended up in the Soviet Union when Hitler and Stalin carved up Poland in 1939. In 1941 he was forced to escape again from his new hometown of Zhytomyr, to be mobilized in December that year. Serving in the coastal artillery, he faced rampant antisemitism—“I couldn’t live, I had to fight every day.” So when his unit was destroyed during battle of Taman in late 1942, he made use of the opportunity to register again under a new name—Artur—and nationality—Polish.63

A separate story concerns Jews who had to survive German occupation or even captivity. For them, adopting a non-Jewish identity was essential to stay alive. In many cases, they used lost ID documents or forged spravki to construct a new identity. Whether they kept this new identity after the war depended on circumstances.

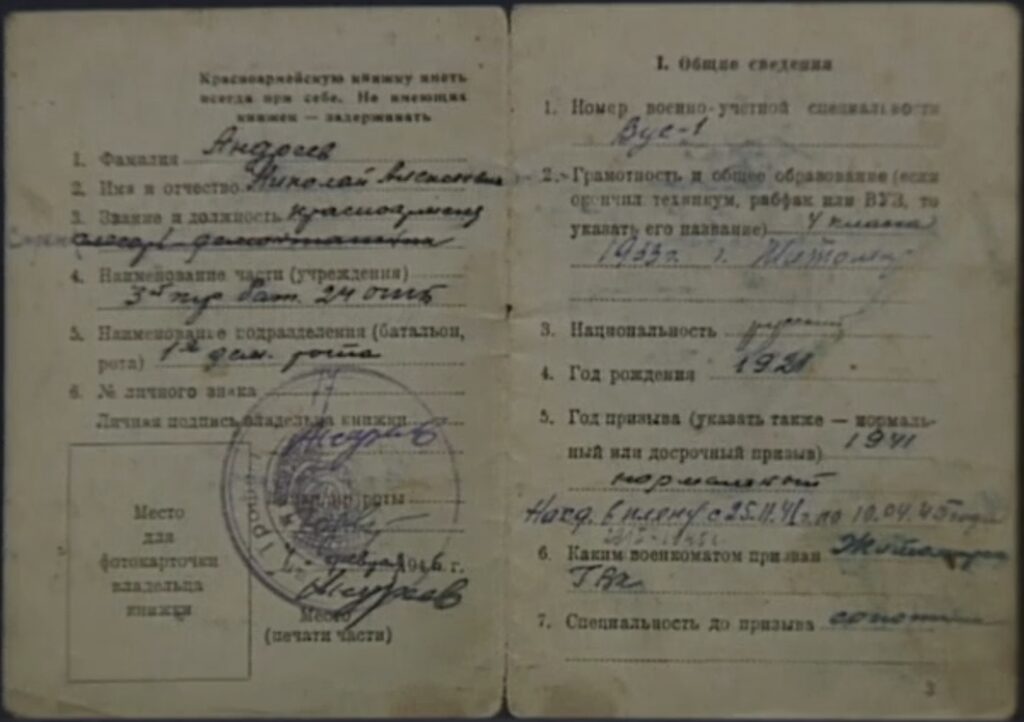

It is interesting to have a look at the biographies of Avrum Faler and Isaak Chebotarev, two Jewish men born in 1921 and living in Zhytomyr. Both were drafted at the start of the war and subsequently captured as POWs. Both were able to escape and adopted fake identities with the help of found documents, becoming a Russian named Nikolai Andreev and a Ukrainian named Mykola Shevchenko respectively. Chebotarev/Shevchenko survived in occupied Ukraine and was drafted into the Red Army after Soviet return, under his Ukrainian name, confirmed by German documents. Faler/Andreev was deported to Germany for forced labor and liberated there. He was then also drafted into the Red Army with his Russian identity. After the war, back in Zhytomyr, both decided to keep their new identities, because, as Cheborarev/Shevchenko puts it, “Because it was easier living as Shevchenko, simply easier.” In their private lives, they continued using their Jewish names.64

Still, the Soviet regime’s representatives did not like the idea of subjects changing their identities. And with the years, informants told the KGB about them. Both were interrogated in the early 1950s. In the end, Faler was forced to return his birth name and ethnicity, whilst Shevchenko was allowed to keep his wartime identity.65 The reasons for this preferential treatment are unknown, but perhaps it had something to do with the fact that Faler, having been in German captivity, was deemed less reliable—whereas Shevchenko was a decorated war hero.

This goes to show, once again, how watertight Soviet bureaucracy was. Over the years, many of the “irregularities” that had occurred during the wartime mess were exposed and eliminated. The logical sequences described above did their job. Still, citizens were not entirely deprived of agency in the face of this paperwork machinery. They could and did pursue their own aims, exploiting whatever room for maneuver the system offered.

- For this blog post I mainly use record groups O.32 (Soviet Union Collection), O.41 (Lists and Documentation of Perished and Persecuted Collection) and O.75 (Letters and Postcards Collection). ↩

- Al’bert Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki (Saint Petersburg: Evropeiskii universitet v Sankt-Peterburge, 2017), 69–90. ↩

- Baiburin, 150–57. ↩

- A similar connection between industrialization and the development of disciplinary methods was described by Foucault: Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (London: Penguin Classics, 2020), 218. ↩

- Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki, 136–43. ↩

- It is no coincidence that the domestic passport was introduced at the height of the 1932/33 famines, which devastated the countryside of Ukraine, the Volga Basin, and Kazakhstan, and forced millions of peasants to seek a better life in the cities. ↩

- Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki, 100–108. Baiburin describes this logic in detail but does not apply the metaphor of “sequences” or “chains”. Rather, he describes the passport system as a “giant sorting machine”: Baiburin, 126. ↩

- Foucault described the “examination” to be “at the centre of the procedures that constitute the individual as effect and object of power, as effect and object of knowledge”: Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 191–94. ↩

- Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki, 120–26. ↩

- Many of its features, such as the distinction between an internal and a foreign passport, continue to exist in most of the Soviet Union’s successor states until this day. ↩

- When the German occupiers held a preliminary census in September 1941, only around 40,000 people were left in the city. After the murder of remaining Jewish population on 19 September, this number dropped to 36,638. M.D., “Perepys Naselennia Zakincheno,” Ukraïns’ke Slovo, September 4, 1941, 4; Census of 1 October 1941, Derzhavnyi arkhiv Zhytomyrs’koi oblasti (DAZhO) r-1153-1-7. According to the USHMM Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, about 7,000 Jews remained in Zhytomyr when the Germans arrived: Alexander Kruglov, “Zhitomir,” in The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, Volume II: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe, ed. Martin Dean and Mel Hecker, trans. Steven Seegel (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 1579–1581. ↩

- I avoid the word evacuees when referring to the refugee population in general, because many of them received little to no help from the state on their flight to the east. See Rebecca Manley, To the Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2009), 48–76. ↩

- Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki, 161–67. ↩

- Manley, To the Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, 149–59. ↩

- Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki, 136–43. ↩

- Manley, To the Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, 184. ↩

- It suffices to glance at the USHMM collection RG-75.002M, which contains registration cards from Uzbek archives. ↩

- Manley, To the Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, 184. ↩

- For example, see this list of 16 April 1943 containing the data of men who succumbed to injuries and diseases in the hospitals of the Black Sea Fleet here. ↩

- Testimony of Leonid Grips, 7 December 2008, YVA O.3 7573865; testimony of Leonid Grips, 24 December 1996, Visual History Archive (VHA) 25138. At the end of the VHA interview, Grips shows the spravka his mother received from the NKVD upon release. ↩

- Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki, 136–43, 161–67. ↩

- See for example the testimony of Avrum Faler, 5 October 1997, VHA 35875. ↩

- O.V. Lavinskaia and V.V. Zakharov, eds., Repatriatsiia Sovetskikh Grazhdan s Okkupirovannoi Territorii Germanii, 1944-1952, Tom 1: 1944-1946 (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2019). ↩

- Thus, Boris Tabachnik, who survived the German occupation and was drafted into the Red Army in late-1944 only returned home in the early 1950s: Tabachnik family papers, USHMM 2000.110; interview with Joseph Tabachnyk, 12 March 2021, conducted by the author. ↩

- This design—sending repatriates home to make sure collaborators are caught—is not described in official Soviet documents (Lavinskaia and Zakharov, Repatriatsiia Sovetskikh Grazhdan s Okkupirovannoi Territorii Germanii, 1944-1952, Tom 1: 1944-1946.), but the logic can be deduced from concrete cases, such as that of Davyd Kozub, USHMM RG-31.018M reel 76, 1557-1684. ↩

- Which does not mean people did not try to travel to other places. See the testimony of Igor Kharpatin, who wanted to return to his hometown of Kyiv when he was repatriated. When he arrived in Rava-Ruska, the first station on Soviet territory, he understood he would be sent to a labor battalion. So he bribed a truck driver and made his way back home: testimony of 5 December 1996, VHA 23867. ↩

- Martin J. Blackwell, Kyiv as Regime City: The Return of Soviet Power after Nazi Occupation (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2016). ↩

- Amir Weiner, Making Sense of War: The Second World War and the Fate of the Bolshevik Revolution (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001), 43–70. ↩

- Karel C. Berkhoff, Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine under Nazi Rule (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2004), 222. ↩

- Weiner, Making Sense of War: The Second World War and the Fate of the Bolshevik Revolution, 114–22. This was the situation in the pre-1939 oblasts of the Ukrainian SSR. In the newly-annexed territories, the dynamics were different. See Diana Dumitru, “Jewish Social Mobility under Late Stalinism: A View from the Newly Sovietizing Periphery,” Slavic Review 78, no. 4 (Winter 2019), 986-1008. ↩

- Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001). ↩

- See, for instance, the letters of Petr Kipnis, who served in the Red Army, to his wife in the rear. A substantial part of his writing is devoted to getting and staying in touch with relatives: YVA O.75/4975. ↩

- Manley, To the Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War, 184–85. Also see the inquiry of Sofiia Tanskaia to the Ministry of Defense about her husband, 17 October 1946, here. ↩

- An interesting example is the postcard from a friend in the army sent to Grigorii Liberman, who was evacuated to the city of Kurgan, asking the latter to help get in touch with “Riva and the kids” (presumably his wife and children) via the “DP department”, i.e. the Evacuees Administration: YVA O.75/5389. ↩

- The father of Boris Tabachnik, who returned to Zhytomyr after the war, only got in touch with his son, who was serving in Germany, in the 1950s. Interview with Joseph Tabachnyk, 12 March 2021, conducted by the author. ↩

- Rudenberg-Geller collection, YVA O.75 4747. ↩

- Gimelfarb collections, YVA O.41 1778 and YVA O.75 4637. ↩

- Ibidem. ↩

- Kipnis-Zubataia correspondence, YVA O.75-4975. ↩

- Another good example is Iadviga and Mykola Dykun, a couple from Zhytomyr. She was of Polish-German descent and worked as a translator for the Germans. When the Red Army advanced on Zhytomyr, they fled westwards to Germany, but in 1945 the French military command handed them over to the Soviet authorities. Their repatriation spravka forced them to move back to Zhytomyr, where the story of their wartime exploits came out and they were persecuted: Dykun filtration files, DAZhO r-5013/1/24267; DAZhO r-5013/1/36052. ↩

- See the investigation files on the Klimenko cousins: USHMM RG-31.019M reel 13, 229-522. ↩

- Testimony of Igor Kharpatin, 5 December 1996, VHA 23867. ↩

- Baiburin, Sovetskii Pasport: Istoriia – Struktura – Praktiki, 161–67. ↩

- Testimony of Faina Gelman, 17 March 1995, VHA 1630. ↩

- Sura Gankina from the town of Romanivka faced this challenge: the local archive was destroyed during the war: testimony of 20 March 1998, VHA 47179. ↩

- See the certification (posvidchennia) that Avram Reznik finished the 10th grade of school in 1941, 14 June 1951, GFHA Holdings Registry 38337, 57. ↩

- See the reference issued to Leonid Gimel’farb, confirming he worked at the Kolkhoz Red Niva in Kursk Oblast from 14 September through 5 October 1941: YVA O.75 4637. ↩

- See the archival reference issued to Leonid Kristal’ by the Belarusian Communist Party Archive in December 1974, confirming he had served in a partisan unit in Baranavichy Oblast, YVA O.32/1031. ↩

- Archive reference, 21 October 1965, YVA O.75/5389. ↩

- See the death certificates of the Mandel’eil’ family, kept by their relative Bronia Emel’ianova. In January 1947, the local civil registration office registered the family of four (a mother and her three children) as “killed by the Germans” on 20 August 1941: YVA O.41/1648. ↩

- Reference by the military tribunal of the Zhytomyr garrison, 13 November 1944, YVA O.75/5399. ↩

- See the response Gersh Fel’dman received from the Red Cross in December 1993 after a last attempt to find out what happened to his evacuated mother during World War II: YVA O.32/587. ↩

- See the interview with Viktoria Didkivs’ka, a teacher at the Zhytomyr Pedagogical Institute in the 1950s: “Moreover, at that time, in 1956, there was still a rule that said: preferably don’t accept those {students} who were under occupation. There were all kinds of obstacles like that.” V. O. Venhers’ka, ed., Zhytomyrs’kyi Derzhavnyi Universytet Imeni Ivana Franka u Spohadakh Vykladachiv (1940-1990-Ti Rr.) (Zhytomyr: Polissia, 2019), 161. ↩

- This is clear from many testimonies. For example, Mira Litvak, in her VHA testimony, describes how that the commission that refused her admission to the Zhytomyr Pedagogical Institute, despite her getting straight As, explicitly told her this was because she was Jewish: Mira Litvak, née Melamed, 11 November 2019, YVA O.3 13717174. Testimonies of non Jewish students confirm there was such a policy. See the interview with Mykola Osadchyi in V. O. Venhers’ka, ed., V. O. Venhers’ka, ed., Zhytomyrs’kyi Derzhavnyi Universytet, 359-365. ↩

- Testimony of Vilen Grinman, 24 September 2020, YVA O.3/14397072. ↩

- Sheila Fitzpatrick, Tear Off the Masks! Identity and Imposture in Twentieth-Century Russia (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005), 14–18. ↩

- Fitzpatrick, 282–300. ↩

- Spravka of Fedor Travkin, Tsentral’nyi derzhavnyi arkhiv hromads’kykh orhanizatsii Ukraïny (TsDAHOU) 1/46/3809 27-28v. ↩

- For instance, Davyd Kozub lied about his age when he was drafted into the Red Army in 1944, in an attempt to obtuse the fact he had collaborated with the Germans. USHMM RG-31.018M reel 76, 1557-1684. ↩

- Sheila Fitzpatrick has pointed out that practices of passing and imposing are particularly prevalent among “marginal groups” in any society: Fitzpatrick, Tear Off the Masks! Identity and Imposture in Twentieth-Century Russia, 12–13. ↩

- Gimel’farb collections, YVA O.41/1778 and YVA O.75/4637. ↩

- Grigoriy Raytzin collection: YVA O.32/953; army registration card for Gersh Raitsin, see here. ↩

- Testimony of Arthur Sukiennik, 23 August 1988, USHMM RG-50.462.0555. Compare the documents digitized by Pamyat Naroda (note his “Jewish self” was never reported missing, just another name that disappeared in the bureaucratic mess of the Red Army) here and here. ↩

- Testimony of Nikolai Shevchenko, 19 October 1997, VHA 37276; Testimony of Avrum Faler, 5 October 1997, VHA 35875. ↩

- Ibidem. ↩