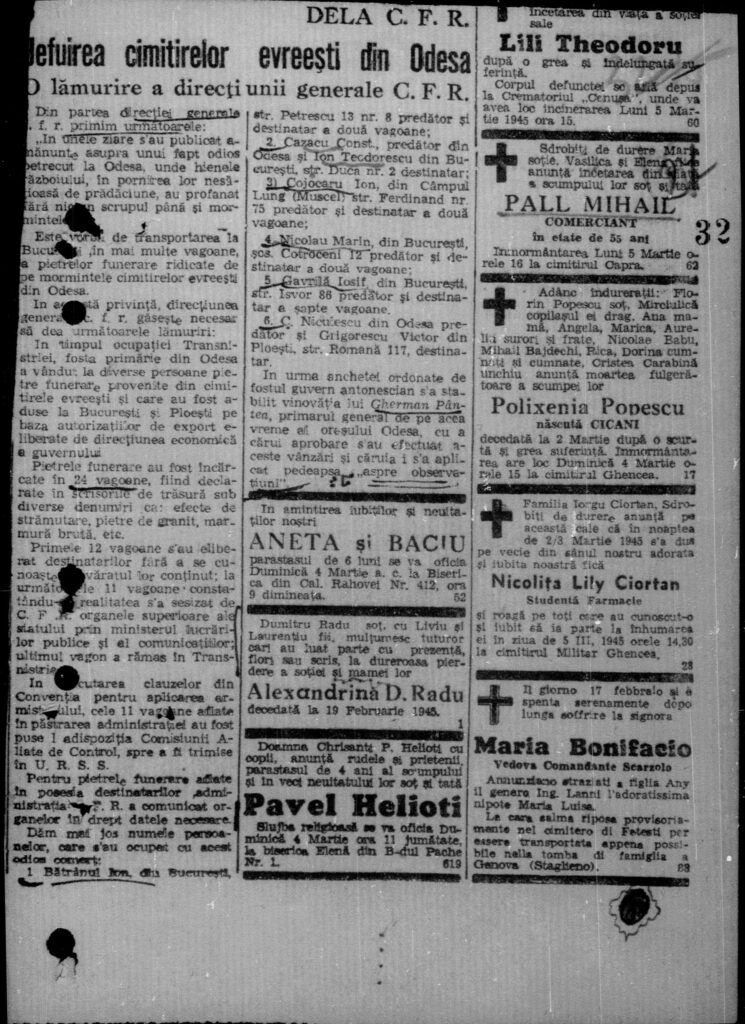

The newspaper article, entitled “Looting of Jewish cemeteries in Odessa,” was probably published in spring 1945. According to it, “the transportation to Bucharest, in several wagons, of tombstones taken from the graves of Jewish cemeteries in Odessa” took place. The Odessa city hall sold the tombstones to various individuals and the mayor Gherman Pântea approved the sales.1 The criminal file on the “tombstones affair” was opened in the name of Gherman Pântea on 29 January 1945 and closed on 23 July 1946. The case was reopened in 1952 and Pântea was sentenced for his illicit business affairs to ten years of forced labour and ten years of civilian degradation with property confiscation but in the end released in 1955.2 This trial represents one of the relatively few post-World War II criminal trials initiated by Romania, with many of those convicted were released after serving only a few years in prison.3

The archival research conducted during the Conny Kristel Fellowship4 has revealed intricate complexities surrounding the case of Jewish cemeteries in Odessa, which was Transnistria’s administrative centre during the Romanian occupation from 1941 to 1944. What was the fate of Jewish tangible heritage, including synagogues and cemeteries, during this period of mass deportation and annihilation of Jews? This aspect of both economic and cultural destruction in southwestern Ukraine during the war and the Holocaust carries a significant moral burden but has received minimal attention in research within both Romania and Ukraine. In the following pages, I will provide context for this issue, look at the actors involved in the “Tombstone Affair” (as mentioned in a state report), and elaborate on how state institutions responded to it.

Transnistria under Romania’s Occupation

The events described in the article cited above occurred from September 1943 till February 1944. In June 1941, Romania had joined Nazi Germany in the war against the Soviet Union. As a gesture of gratitude, Hitler offered Transnistria to the Romanians, and thus making Romania the only ally of Nazi Germany to occupy Soviet territory. The city of Odessa, which played an important strategic and commercial role in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, was of great value to Romanians, who had to determine how to administer it. Odessa was a melting pot of ethnic groups, such as Ukrainians, Jews, Russians, Poles, Moldovans, Armenians and more. During the Russian Empire, the local Jews were targeted in a series of pogroms (1821, 1859, 1871, 1881 and 1905), which continued during World War I and the Russian Civil War.5 Nevertheless, the situation of the Jews improved significantly in the interwar period. The Soviet nationality policy promoted the cultural development of Jews, their integration through employment in various public functions, and introduced legal punishment for antisemitic behaviour. Cases of Jewish segregation in daily life did not disappear entirely; nevertheless, the relations between Jews and non-Jews had improved.

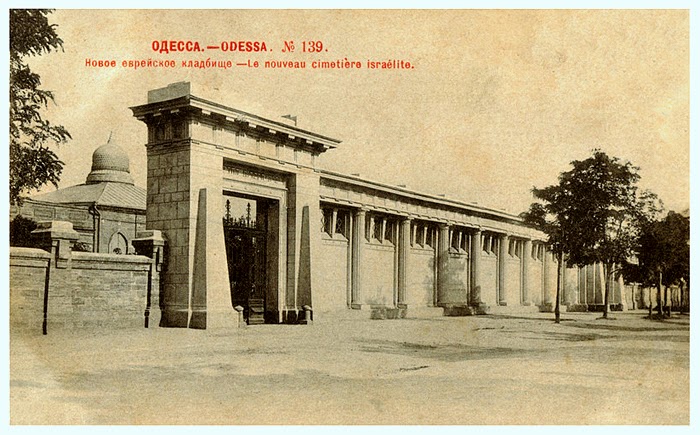

Before World War II, the Odessa Jews numbered 165,000 inhabitants, or 30 percent, making Odessa the third largest Jewish population in the world.6 In 1926, 76.1 percent claimed Yiddish as their mother tongue. The Jewish cultural heritage in the Ukrainian SSR was treated equally by Ukrainian scholars who perceived and studied it as an integral part of the Ukrainian national heritage.7 In 1927, the Jewish Museum, called the Mendele Moykher-Sforim All-Ukrainian Museum of Jewish Proletarian Culture, was established in Odessa.8 Documentation of the synagogues and cemeteries was one of the museum’s tasks. The Odessa branch of the Scientific-Research Department of Jewish Culture at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences researched museum manuscripts dedicated to Jewish history and culture.

At the same time, the Soviet authorities pursued a dual policy towards the Jewish tangible heritage. Following the adoption by the Bolsheviks in January 1918 of the decree “On the Separation of the Church from the State and the School from the Church”, the closure campaign of churches and synagogues was launched. The Jewish cemeteries were declared state property under the administration of the municipalities. The Soviet authorities treated the cemeteries in a careless way, since these were associated with religious belief and rituals that had no place in a Socialist society.9 The example of the Old Jewish cemetery in Odessa destroyed in 1936, is significant in this regard.

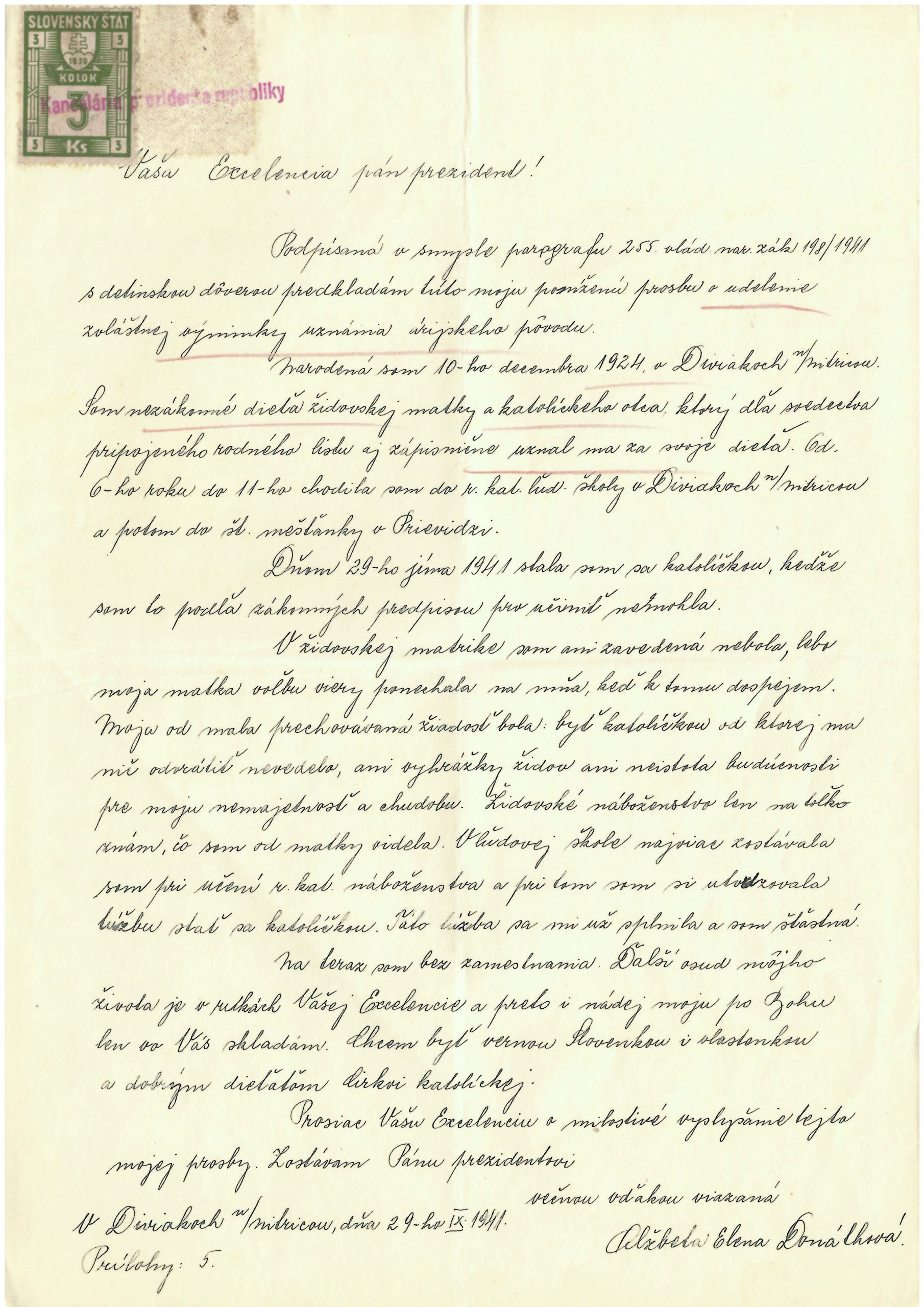

In neighbouring Romania, the destruction of Jewish cemeteries occurred simultaneously with the radicalisation of the antisemitic policy. In October 1940, Ion Antonescu considered that moving the cemeteries outside Bucharest city limit would solve the “sanitation issue,” which was under responsibility of municipal authorities. The Union of Jewish Communities of the Old Kingdom protested before Antonescu against the expropriation. The letter of protest, signed by the president of the Jewish Federation Wilhelm Filderman, argued that the Jewish religion did not allow exhumations and that “the closure of cemeteries means the ruin of our communities”, since the Jewish schools and hospitals benefitted directly from the subsidies gathered by the cemeteries. Since other cemeteries functioned in the city, “there can be no crueller suffering than the inequality of the dead, the suppression of the worship of the dead, the degradation of our religion and of ourselves as people and believers, than to be prevented from burying our dead according to the commandments of our Bible, when cemeteries of all denominations are allowed to function both in the city center and outside the city.”10 The same address was issued to the Bucharest mayor the next day.11 In a government response, Filderman was assured that the Bucharest cemeteries remained functional; nevertheless, the Jewish organisation complained of the difficult conditions in which the buries took place.12 The state antisemitic policy in Romania, which was on the rise since the middle 1930s, thus led to the situation in which Jewish cemeteries were presented as a “threat” to public hygiene and urban modernisation.13

After Romania entered the war on the side of Nazi Germany in June 1941, the urban “sanitation” of Jewish cemeteries went hand-in-hand with the racial purge of Jews and Roma. The cemeteries of the oldest Jewish communities in northern Moldavia were partially or completely destroyed. In the summer of 1942, the old Jewish cemetery in Vaslui was destroyed and the property transferred to the municipal authorities. The old Jewish cemetery in Piatra Neamț suffered the same fate. In Constanța, the protest of the Jewish community did not stop the city hall from using the tombstones taken out from the Jewish cemetery for road construction, “to mark on them the names of the roads and distance.”14 Trenches were dug in the Jewish cemetery in Ploiești; the bones thrown into the street were collected by local Jews and reburied.15

In Transnistria, occupied by Romania in the summer of 1941, the local public administration was placed in the hands of Bessarabian-born officials. They had studied and worked in Odessa, when Bessarabia was part of the Russian Empire, accumulated political experience during World War I and the 1917 Russian revolution and succeeded in proving their loyalty to the Romanian state during the inter-war period, when Bessarabia united with Romania. Such was the case of Gherman Pântea, mayor of Odessa between 1941 and 1944. Most of the employees in the Odessa city hall were recruited by Pântea among his former peers whom he knew from Bessarabia. A network of Bessarabians was established in Odessa, who were entrusted with the management of local affairs and had a free hand in the region.

As Charles King puts it, the public employees from Bessarabia were “products of the borderland.”16 Those who came to serve in Transnistria after 1941 knew the customs and the language of the local population who spoke Russian, Ukrainian, and Romanian, and lived in the region’s proximity. While in Bessarabia, they learned how to adapt a regime change and take advantage of social and political instability. While many went to Transnistria to support Ion Antonescu’s alliance with Hitler against the Soviets, they received legitimisation from the Antonescu regime to also loot and bribe in Transnistria, so they took every opportunity to enrich themselves.17

Annihilating the Jews, Robbing the Region

After the explosion of a bomb at the Romanian military headquarters in Odessa on October 22, 1941, which killed 67 people, Antonescu ordered a mass killing of local Jews. Around 20,000 Jews were killed and deported outside the city, the remaining 35,000 were deported to Dalnik and Slobodka in November that year, the rest of the 19,295 Jews were deported in February-March 1942 to Bogdanovka, Domanevka, and Akhmetchetka, the remaining Jews were murdered in the city. After the massacre, under the pretext of “military necessity,” a massive plundering initiative (“Operation 1111”) occurred. The looting of abandoned houses by non-Jewish neighbours, the military and public servants also became regular. After Stalingrad, when the Romanians acknowledged that the war course changed in favour of the Soviets and the plans to annex Transnistria faded away, they rushed to “evacuate” factories and plants, tractors and trams, wood and foodstuffs with the aim of depriving the region of every resource. Later Antonescu admitted that “all the fortune collected in Transnistria … is being squandered;” the Romanians encountered difficulties storing it inside Romania. At the same time, museum artefacts, paintings, musical instruments, theatre sets, books and other cultural objects were being smuggled out of Odessa, and private property was being stolen from Jewish homes and the warehouse in the city centre where deported Jews had to leave their valuables.18

General Constantin Potopeanu, who replaced Gheorghe Alexianu in March 1944 to carry out the transfer of administrative power to the German military command, reported that Romanian officials had many opportunities to get rich in Transnistria, e.g. by negotiating direct prices for goods with merchants, stealing goods entering or leaving the region, facilitating the exchange of Lei into Reichskreditkassenscheine (R.K.K.S.), favouring commissions, trading through intermediaries, carrying out theft and smuggling, etc. The smuggling could be carried out by various means of transport, such as auto, train, ship, or even plane. Already in February 1943, Potopeanu received a notification from Ion Antonescu to investigate, “through the military channels,” the destination of 100,000 tons of cereals, 19,000 tons of foodstuff and 30,000 tons of materials and other objects. He did not proceed: “we were later told that most of these goods would have gone abroad.”19 Potopeanu was unsatisfied with the mayor Gherman Pântea who carried out a “superficial” transfer of local administration to the Germans in March 1944.20 He shared with Constantin Păunescu, inspector of the Ministry of the Interior, that “the tombstone affair is really crap.”

The “odious trade”

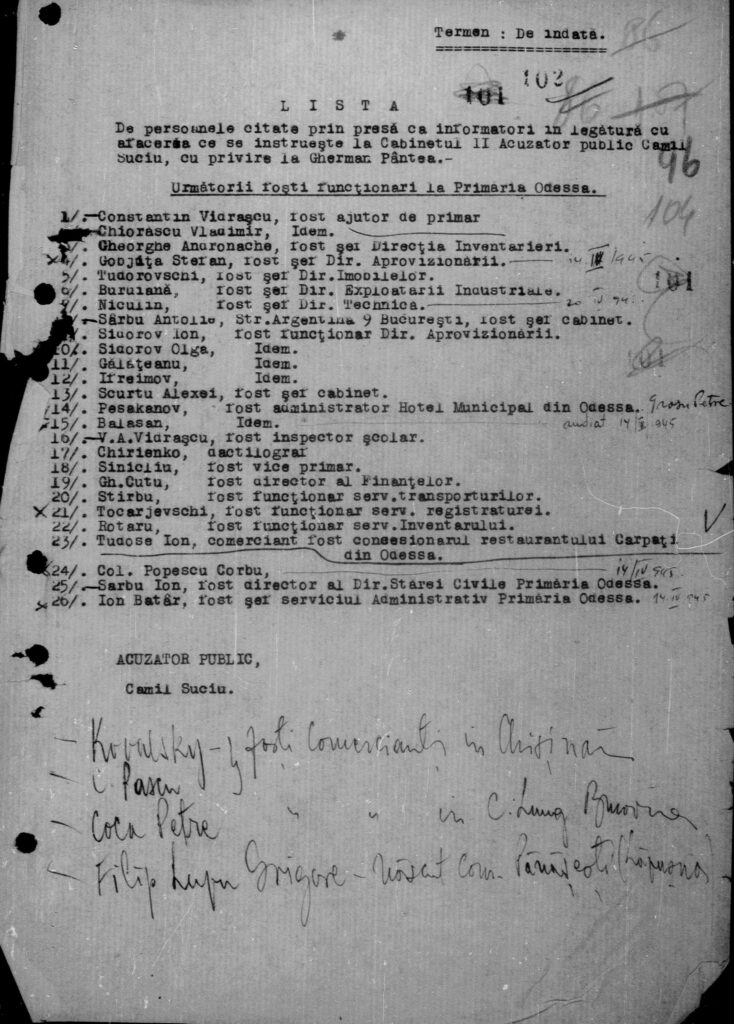

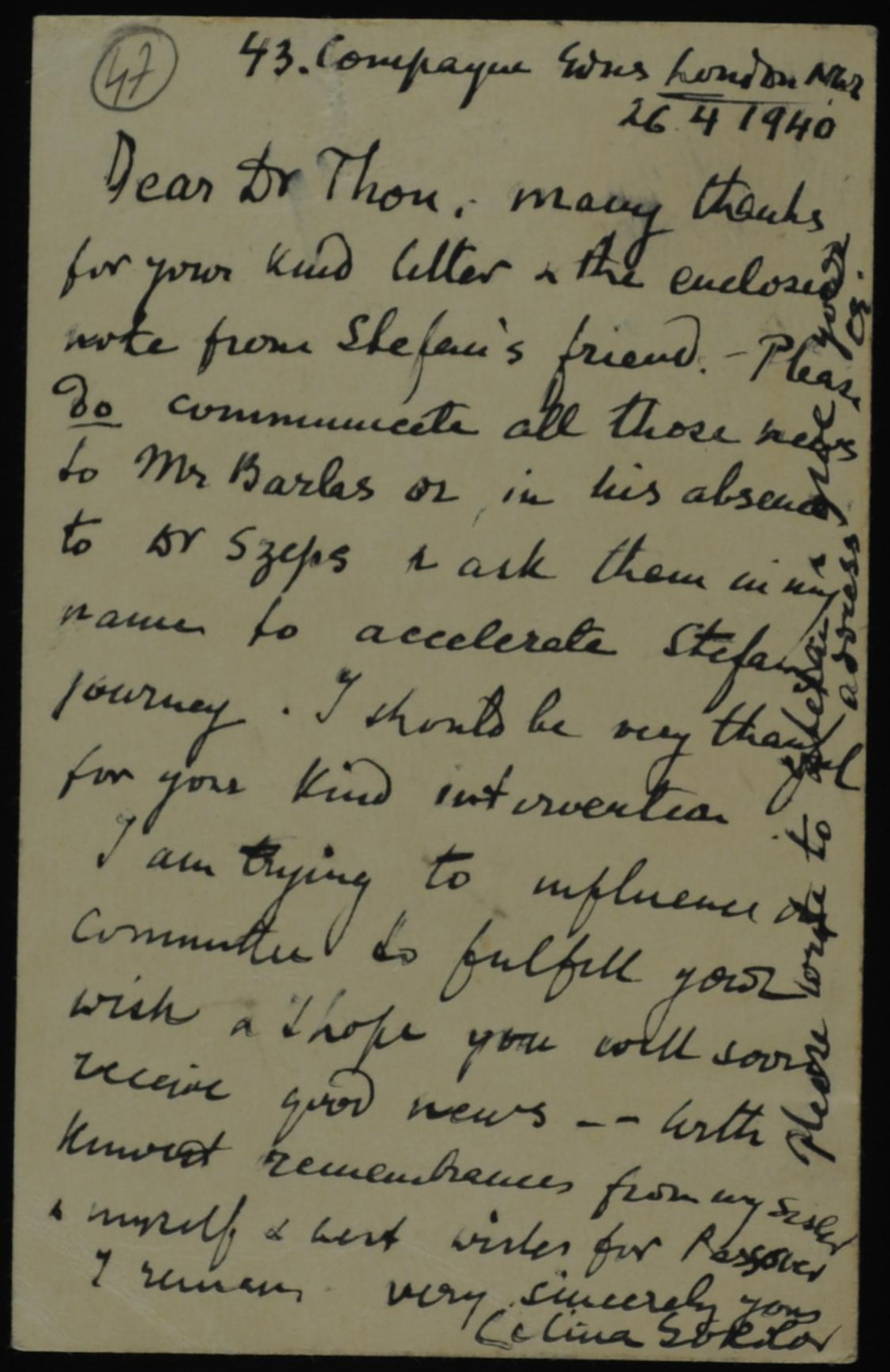

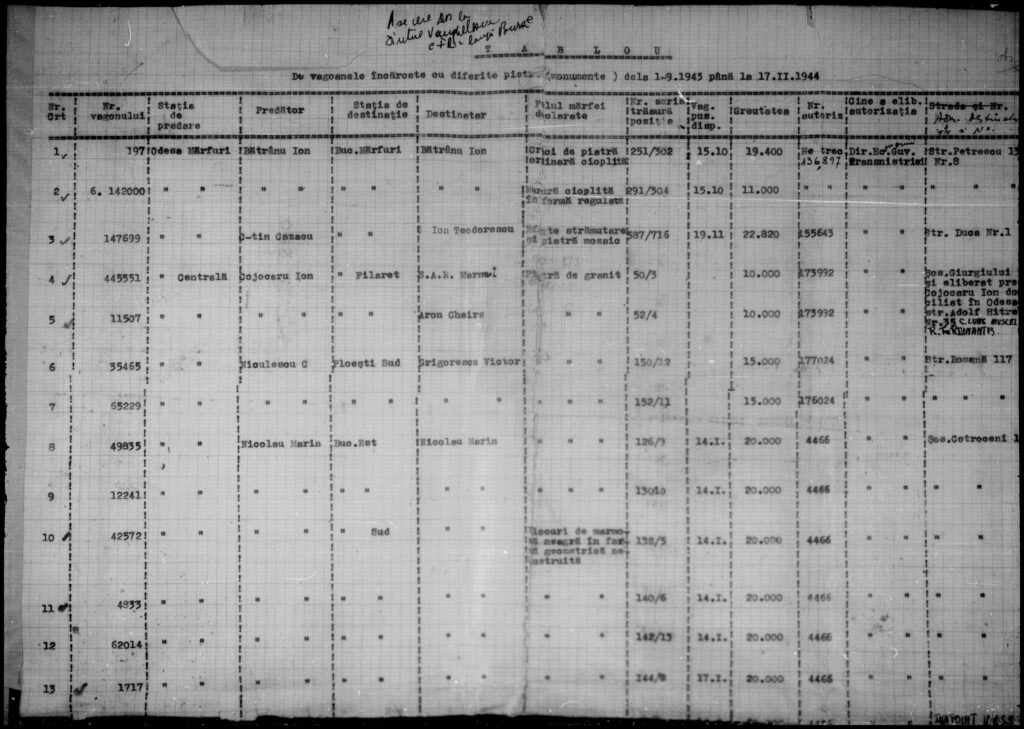

According to the above-cited newspaper article, the Odessa city hall sold the tombstones from the local Jewish cemetery. The individuals who received, subsequently, the transport permits from the Economic directorate of Governorate of Transnistria, transported them inside Romania. The stones were loaded in 24 wagons, the transported goods carrying various names, such as relocation effects, granite stones, rough marble. The goods held in the first 12 wagons were brought to Bucharest and Ploiești, where they were released without being checked. Only at the later stage had the Railroads management turned to the government officials on the matter. As a result, 11 wagons with tombstones were transmitted to the Allied Control Commission to be sent back to the USSR based on the Convention for the implementation of the Armistice of September 12, 1944, which recognised the defeat of the Romanian army in the war against the Allies and imposed on Romania a series of onerous clauses. The names of several people who participated in the “odious trade” were indicated, namely Ion Bătrânul from Bucharest, Constantin Cazacu from Odessa who worked with Ion Teodorescu from Bucharest, Ion Cojocaru, Marin Nicolau, Iosif Gavrilă from Bucharest, C. Niculescu from Odessa who worked with Victor Grigorescu from Bucharest. According to the article, the mayor of Odessa, Gherman Pântea, approved or carried out the sales. The government’s investigation found Gherman Pântea guilty and sentenced him to a “severe reprimand.”

The Odessa Railroads Company had apparently not been paid for the service and therefore threatened to take Pântea to court. Although Pântea claimed that the tombstones were destroyed, a good part of them appeared to be in good condition. The Romanian Railways thus publicly confirmed the looting of Jewish cemeteries in Odessa taking place. Further research indicated that during the 1941-1944 Romanian occupation of Transnistria, the Odessa municipality sold tombstones presumably from the New (Second) Jewish cemetery, established in 1873.

The investigation into the “tombstones affair”, ordered by Antonescu himself, was apparently unfavourable to Pântea who was personally appointed by Antonescu. Pântea was characterised by his entourage as an “intelligent, daring, adventurous, and businesslike man.”21 One of the investigators, Gen. Constantin Popescu concluded after his trip to Odessa that “the city hall was selling the tombstones destroyed by the bombing in order to change the pitiful appearance of the cemetery” and that the blame for the situation lay with the city commission which had approved the selling but not the mayor Pântea.22

Ing. Nicolae Niculin testified that some of the marble from the damaged tombstones was used to repair various damaged buildings in Odessa.23 Petre Grosu-Peșacanov, a former employee in the Chișinău city hall who was recruited by Pântea to serve in Odessa, testified that he “heard from both the locals and the Romanians in Odessa that Pântea was doing big business and was interested in commercial deals.”24 The relations with some local merchants who possessed the hotel “Bristol” and the restaurant “Romania” in Odessa were recalled. The memoirs of local Odessans also contain such recalling.

The regime favoured the unlawful enrichment of civil servants, since cases of punishment were rare. The Romanian officials saw the “tombstones affair” as a means of making money and the merchants played the role of intermediaries in this equation. The chart below contains detailed information on the merchants whose names appeared in the above newspaper article, the quantity of the bought tombstones and the authorisation number.

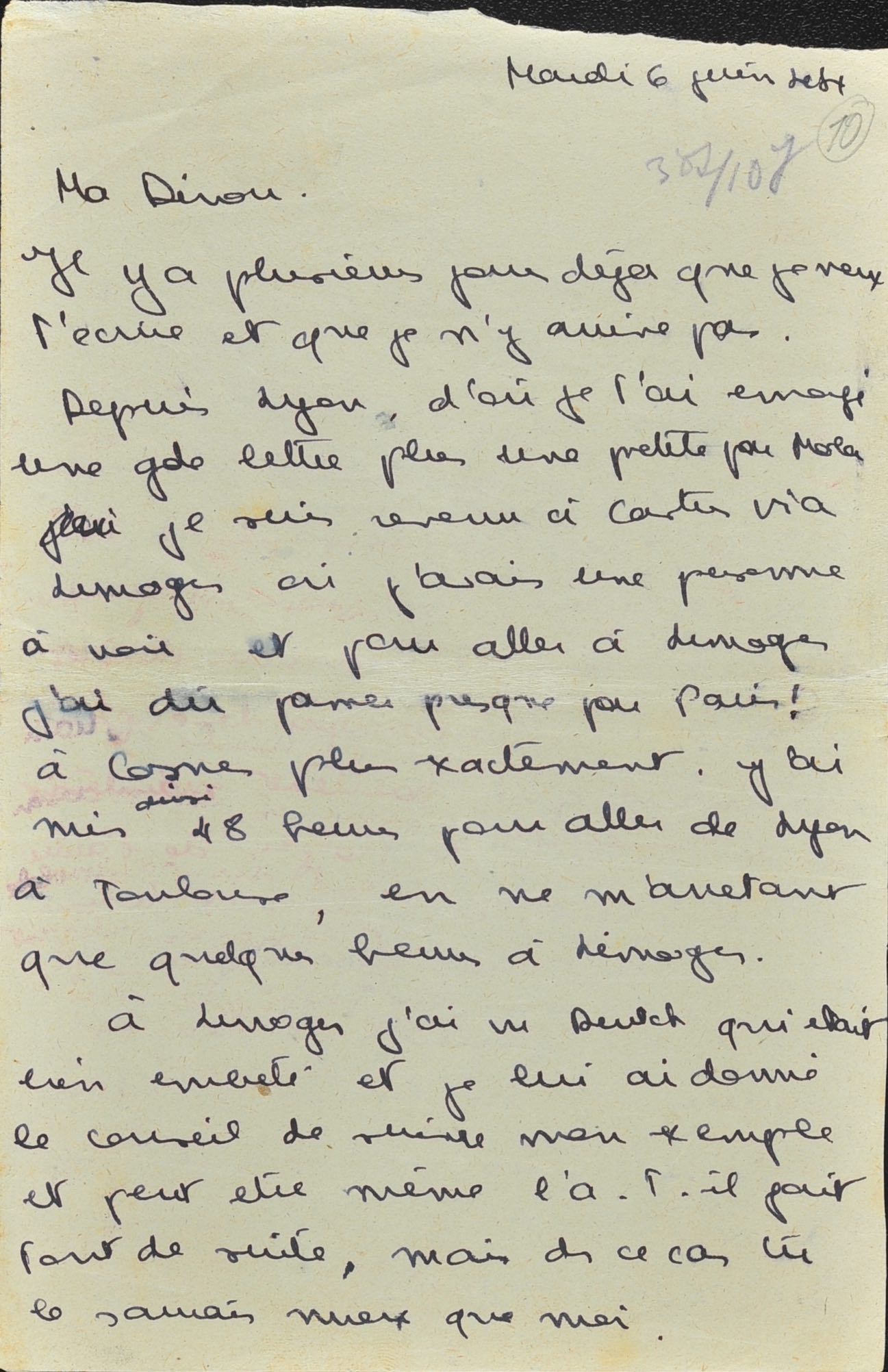

In November 1943, Ion Cojocaru, who had just liquidated his commercial activity of confectionary, received a proposal to associate with two other merchants and set up a “company for the purchase of black granite, sold by the Odessa city hall.” He invested his entire capital of 20,000 R.K.K.S. in the affair. After the train with the granite tombstones reached Bucharest, one of the associates, Ion G. Caracaș from Fetești, Ialomița county, sold them to the Vignali & Gambara Company in Bucharest.

Marin Nicolau acquired at the local auction 10 wagons of marble “from the tombstones, partly broken and scratched” as a result of the bombing of the Jewish cemetery in Odessa, and for which he testified paying to Pântea 33,000 R.K.K.S. In Bucharest only 4 wagons were released. The railway management agreed to release the other 6 wagons on the condition of an additional payment, on the ground that marble was a valuable good. However, the Minister of Public Works, Ata Constantinescu, did not approve the release. On March 10, 1944, Marin and other merchants were invited to his office, where they were informed that “this stone should not be bought by us and that the Transnistrian Governorate should not have sold it, and [he] instructed us not to sell any stone, because this stone is to be sent back to Odessa.” To that date, he succeeded to sell 2 wagons of marble to the SA „Marmor” company in Bucharest but claimed to have invested 4,959,600 Lei in the remaining 8 wagons.

Another buyer, Anatolie Sârbu, testified that the cemetery administration, led by a certain Ion Sârbu – who might have been a relative – authorised the sale of tombstones, “used, deposited already in 1925 by the Russians and others as the result of the bombardment of Odessa.”25 On March 10, 1945, the secretary of the city hall, Alex Cosmescu, testified that Anatolie Sârbu, who was responsible for returning the tombstones to Odessa, stated that the sale had taken place with the approval of the Governorate.26

Iosif Gavrilă also stated that he had paid all the required taxes, had possessed the necessary authorisation, and had spent 5,461,000 Lei for acquiring 7 wagons of marble, therefore, “I can’t stand the treatment of a crook, profiteer of clandestine shipments and stolen goods.”27 Constantin Cazacu who, in February 1943, was authorised by the Odessa city hall to open a restaurant in the city, transported in November of the same year 10 tombstones to Bucharest for personal use. He paid a certain amount to the cemetery administration, but was exempt from any commercial and custom taxes.

At the time of the transactions, Nicolae Bozie-Codreanu, the regional director of the Odessa Railways testified that “the Russians, found the tombstones in a warehouse in the process of dismantling some cemeteries and used to sell them. After the bombings, more tombstones were stored there.” The results of the above-mentioned investigation ordered by the Ministry of Interior would not be known to him, since the Railways “did not have an interest in it.”28 In addition, he testified that that the Trophy Bureau29 also transported military transports that was not controlled by the Romanian Railways and that in 1943 mayor Gherman Pântea used to send “household items” to Chisinau by train. Despite the rumours that circulated among the local population and the testimonies this could not be proven.

Towards the erasure of Jewish memory?!

The testimonies of Jewish survivors from western Ukraine and today Poland under German occupation are full of recollections on the deliberate destruction of Jewish cemeteries. In Galicia, cases of destruction of Jewish cemeteries were often registered. Thus in Zbaraz near Ternopil the destruction of tombstones in Jewish cemeteries became part of anti-Jewish propaganda marches, carried out by Ukrainian local priests and activists in July 1941 who claimed that the Nazi-Germans purged Ukraine from the Jews.30 In Rava-Rus’ka, located near the Ukrainian-Polish border, after the deportation of around 2,200 Jews to Belzec, local Jews were forced to destroy the old Jewish Cemetery and break up the tombstones, which were to be used in road construction. This was part of the destruction of the Jewish community with its history dating back to the 16th century.31

The interned Jews, usually local people, were often forced to break up the tombstones and carry them out of the cemetery. Thus, Maria Moiseyevna Tribun used to work it the Jewish cemetery near the Polonnoe ghetto: “Often we were forced to go to the Jewish Cemetery and destroy the gravestones on the graves of our own loved ones. Once a stone fell on a young woman’s foot and smashed her toes. She made an attempt to step aside so she could wash her wound and apply a bandage. A guard accused the girl of escaping, and while her father and others watched in horror, the guard shot the girl.”32 O. Lochkin who lived the ghetto near Polonnoe recalled that “the fascist barbarians made those people destroy the monuments in the Jewish cemetery; those who refused to do it were shot on the spot. Now we see that almost half of the monuments in the cemetery are not there anymore.”33 Anna Moiseyevna Kalika from Odessa, who lived through several deportations in 1942, experienced the same situation in the Shepetovka ghetto: “Every day we were doing some senseless work under the supervision of guards, like rolling the gravestones from one place to another at a cemetery.”34 In Novolabunya, “every day we had to work, but it wasn’t any kind of a useful job. We simply were supposed to shake the stones in the Jewish cemetery. To work there was very painful, the Germans whistled and giggled while making us desecrate those graves. But what could we do being under their automatics and sharp-teethed German dogs?” The broken-up stones were used for road construction in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine.

The “tombstones affair” and the controversial role of the mayor of Odessa seems similar to the case of Thessaloniki, where local actors initiated and profited from the destruction of the Jewish cemetery.35 This and other cases on the fate of Jewish cemeteries during the Holocaust in Eastern Europe show that the destruction was part of the cultural violence against Jews. Both individuals and communities were targeted, the cemetery being part of the Jewish tangible heritage. The destruction of cemeteries was, as Noa Krikler has recently argued, “a dimension of genocide itself.”36 Odessa offered a local context of extreme violence, in which the fate of the Jews was predetermined. In such circumstances, the logic of the “Tombstone Affair,” which did not lead to the cemetery’s destruction but added to its severe damage – was developed around the “cleansing of the terrain”37 of Jews in the Romanian-occupied territory, on the one hand, and the greedy interest of making commercial profit from the unprotected Jewish heritage, on the other.

After World War II, the destruction of Jewish cemeteries continued. Thus, the Soviets erased Vilnius’s historic Jewish graveyard in Šnipiškė, the place remaining at the centre of controversy up to today. A similar fate befell the Jewish cemetery in Chisinau, where a zoo and a public park were built on top of its old part. Fortunately, the tombs of the victims of the 1903 pogrom survived.38 Up to today the old tombstones are used in construction or road paving. In Lviv, local administration formally decided to stop using Jewish gravestones in road paving in 2013. As Omer Bartov put it, such and other occurrences lead towards the erasure of Jewish memory from the (Ukrainian) public consciousness. Therefore, the task of preserving local Jewish cemeteries as part of the Jewish heritage and the local and national history remains an urgent one.

Little is known about the fate of the tombstones stolen and sent to Romania during the war. However, the fate of one tombstone can be traced. After the war, the marble monument at the grave of the popular Jewish poet Semyon G. Frug, founder of the new Jewish poetry who died in 191639, was depicted in Bucharest. After the proclamation of the State of Israel, the Jewish community in Romania decided to send it to Tel Aviv, where it was installed on the Alley of the Poets.40 When the destruction of the Second Jewish Cemetery began in the early 1970s, the remains of Semyon Frug and several other famous Jewish personalities were moved to the nearby Second Christian Cemetery (then the International Cemetery). On the centenary of the poet’s death in 2016, a new gravestone was erected, similar to the one now in Israel.41

The case study warrants further exploration; however, at this stage, it provides new insights into the local dynamics of the war and the Holocaust in southwestern Ukraine. It also raises pressing questions about the preservation of Jewish cultural heritage in Eastern Europe, which is currently under threat, most dramatically due to Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine.

- Jefuirea cimitirelor evreești din Odessa, n.d., USHMM Archive, RG-25.004 Selected Records from the Romanian Information Service, 1936-1984, reel 30, f. 32. ↩

- CNSAS Archives, P 077564, vol. 2 Ancheta Pântea Gherman și alții. ↩

- See Andrei Muraru, “Romanian Political Justice. The Holocaust and the War Criminal Trials: The Case of Transnistria,” Holocaust. Studii și cercetări, X, no. 11 (2018): 89-184. ↩

- I express my gratitude to the International Institute for Holocaust Research – Yad Vashem and the Elie Wiesel National Institute for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania for their generous host. ↩

- See Sasha Senderovich, How the Soviet Jew Was Made, Harvard: Harvard University Press 2022. ↩

- Odessa, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/odessa, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- Vladimir Levin, „Jewish Cultural Heritage in the USSR and after Its Collapse,“ in Eli Lederhendler (ed.), Becoming Post-Communist: Jews And The New Political Cultures Of Russia And Eastern Europe (New York, 2023; online ed., Oxford Academic, 23 Feb. 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197687215.003.0006, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- The Jewish writer Mendele Moykher-Sforim (1835-1917) is considered the founder of modern Yiddish literature. He died in Odessa in 1917, 10 years prior to the opening of the museum. ↩

- Mordechai Altshuler, “Jewish Burial Rites and Cemeteries in the USSR in the Interwar Period,” Jews in Eastern Europe, no. 1–2(47–48) (2002): 85–104. ↩

- Domnule General, October 17, 1940, Yad Vashem Archives (YVA), 3687861 Filderman, f. 131-132. ↩

- Domnule Primar general, October 16, 1940, YVA, 3687861 Filderman, f. 157-158. ↩

- Domnule Primar general, November 1, 1940; Domnule Primar general, December 11, 1940, YVA, 3687861 Filderman, f. 195, 284. ↩

- On the Jewish Cemetery in Bucharest, see Adrian Cioflâncă, Cimitirul din centrul Bucureștiului distrus de Ion Antonescu, https://www.scena9.ro/article/cimitir-evreiesc-bucuresti-antonescu, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- Jean Ancel, Contribuții la istoria României. Problema evreiască, 1933-1944, vol. 2, p. 2, București: Hasefer, 2003, 52. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Charles King, Odessa: Genius and Death in a City of Dreams, New York: W. W. Norton, 2011, 240. ↩

- Svetlana Suveica, Pianos and Paintings from Transnistria: The Plunder of ‘Cultural Trophies’ During the Romanian Occupation (1941-1944), The Journal of Holocaust Research, 36:4, 261-280, DOI: 10.1080/25785648.2022.2122140. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Declarațiune, March 6, 1945, RG-25.004, reel 30, f. 203. ↩

- Proces-verbal, March 12, 1945, RG-25.004, reel 30, f. 47v. ↩

- Proces-verbal, întocmit de Niculin Nicolae, April 20, 1945, f. 95. ↩

- Proces-verbal, 14.04.1945, f. 106v. ↩

- Declarație Ing. Niculin Nicolae, ANIC, fond Gherman Pântea, inv. 1646, d. 5, f. 95. ↩

- Declarație Petre Grosu-Peșacanov, ANIC, fond Gherman Pântea, inv. 1646, d. 5. ↩

- Proces-verbal, March 9, 1945, RG-25.004, reel 30, f. 43v. ↩

- Proces-verbal, Mrch 10, 1945, RG-25.004, reel 30, f. 45v. ↩

- Declarație, November 13, 1944, RG-25.004, reel 30, f. 55v. ↩

- Declarație, March 9, 1945, RG-25.004, reel 30, f. 44v. ↩

- Established in 1941 by Ion Antonescu, the Trophy Office was responsible for the extraction of industrial and cultural goods from Transnistria. ↩

- See Wendy Lower, Anti-Jewish Violence in Western Ukraine, Summer 1941: Varied Histories and Explanations, in The Holocaust in Ukraine. New Sources and Perspectives, USHMM 2013, 145-223, here 147. ↩

- In 2015, a memorial site from the remaining tombstones was erected at Rava-Rus’ka, http://www.protecting-memory.org/en/memorial-sites/rava-ruska-en/, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- I ought to tell… (Memoirs of the Former Prisoner of the Polonnoye Jewish ghetto), by Maria Moiseyevna Tribun, https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/polonnoye/pol027.html, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- The Difficult Way, http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/polonnoye/pol027.html, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- Anna Moiseyevna Kalika, Memoirs of a Former Prisoner of a Jewish Ghetto, transl. by Stan Pshonik, http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/polonnoye/pol027.html, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- See Martin Barzilai, Cimetière fantôme – Thessalonique, Créaphis Editions 2023; Leon Saltiel, “Dehumanizing the Dead. The Destruction of Thessaloniki’s Jewish Cemetery in the Light of the New Sources,” Yad Vashem Studies, vol. 42, no. 1 (July 2014): 1-35. ↩

- For further reading, see Noa Krikler, Killing the dead: The logic of cemetery destruction during genocidal campaigns, Nations and Nationalism 2023, 1-17, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nana.12956, accessed October 2, 2023. ↩

- The term (curățarea terenului in Romanian) was used in Antonescu’s secret orders about the destruction of the Jews and is synonym with the German “final solution.” On the implementation of Romanian racial policy in Transnistria, see Vladimir Solonari, Purifying the Nation: Population Exchange and Ethnic Cleansing in Nazi-Allied Romania, Washington DC, Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2009. ↩

- Cimitirul Evreieisc, https://audiowalks.centropa.org/ro/oprire/ro-judischer-friedhof-mit-trauersynagoge/, accessed June 20 2023. ↩

- For a detailed biography and an analysis of Semyon G. Frug’s work, see the contribution of Leonid Berdnikov: Sejatel.’ Natsional’nyi evreiskij poet Semyon Frug, Chajka. Seagul Magazine, 11 June 2021, ↩

- Pam’jat‘i pam’jatnik, by M. Vlagin, Migdal‘ Times, no. 145, https://www.migdal.org.ua/times/145/32476/, accessed 2.10.2023. ↩

- V Odesse otkryli pam’atnik izvestnomu evreiskomu poetu i publitsistu Semyonu Frugu na Vtorom Khristianskom Kladbishche, https://slovo.odessa.ua/ru/novosti/14815-otkrytie-pamyatnika-izvestnomu-evreyskomu-poetu-i-publicistu-semenu-frugu-na-vtorom-hristianskom-kladbische.html, accessed 2.10.2023. ↩