For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

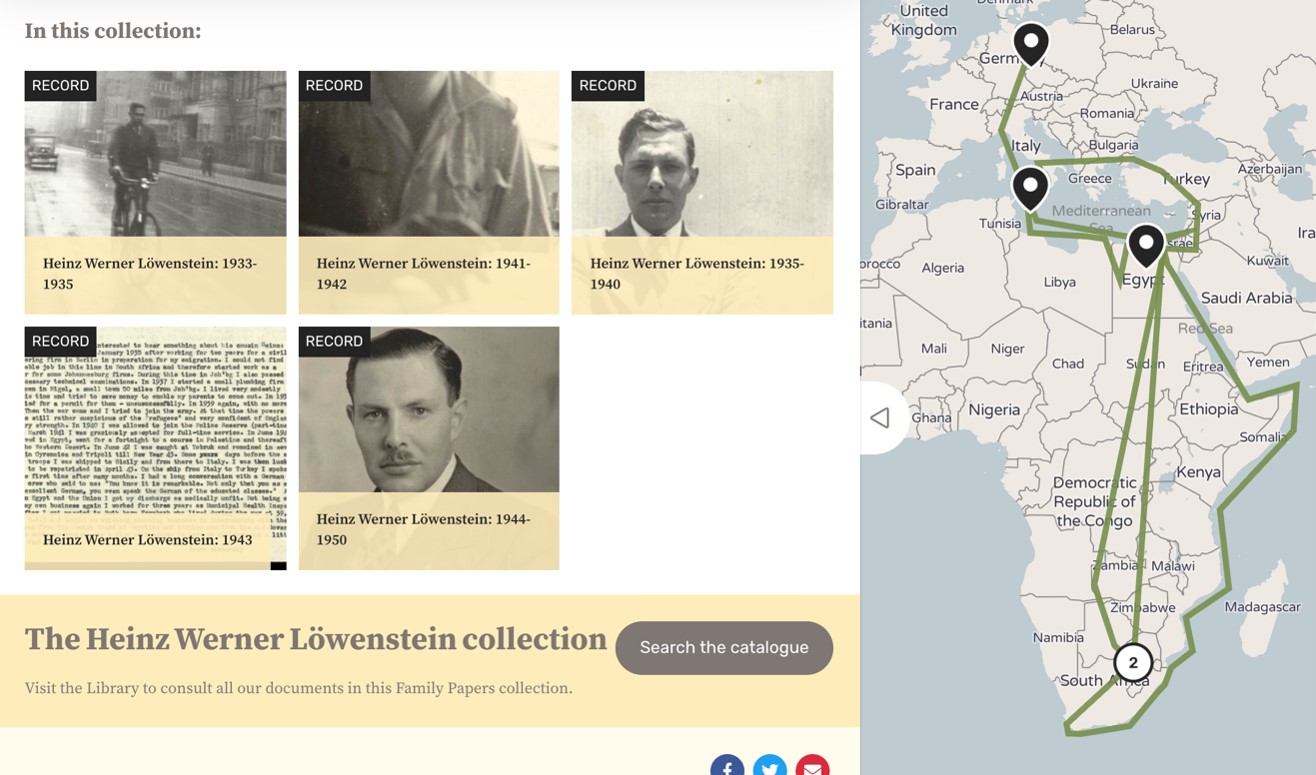

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

I was born in Soviet Ukraine. According to the memory politics of this state, we were not told anything about the Holocaust as children, and for a long time this topic was terra incognita for me. During school lessons about World War II, which was then called the “Great Fatherland War,” we heard about the victorious heroism of Soviet soldiers and the Red Army. But the voices of the victims sounded only faint and muffled—if they were heard at all.

On one of the monuments dedicated to Second World War in Mizoch, my hometown, there was a text about people of “Jewish origin”. These words were confusing, because at that time Mizoch was entirely Ukrainian. We were not told about the history of the Jews.

Much later I learned that in 1942 several thousand Jews were killed in the town. The (clearly overestimated) data of the Extraordinary State Commission stated that 3,700 victims were murdered.1

My interest in these events prompted me to write my bachelor’s and master’s theses on this topic. At the time, however, the legacy of Soviet historiography raised more questions than it answered. Crimes against Jews were described with the euphemism of the suffering of “Soviet civilians”. The fundamental Soviet work local history in Ukraine, The History of Towns and Villages, is a case in point. It makes no mention of the fact that Jews were killed in Mizoch. To be precise, it states that “on 14 October 1942, 1,500 people were shot in the village, and by January 1943, about 3,500, mostly elderly people, children, and women”.2 Thus, the national component was not pointed out. Publications in the press were propagandistic rather than informative, written in the context of the Soviet narrative with an emphasis on the struggle against fascism. They were often rife with factual errors and inaccuracies. For example, an article by Iurii Los claimed that the Mizoch tragedy took place in the summer of 1943, while the German “action” actually took place in the fall of 1942.3

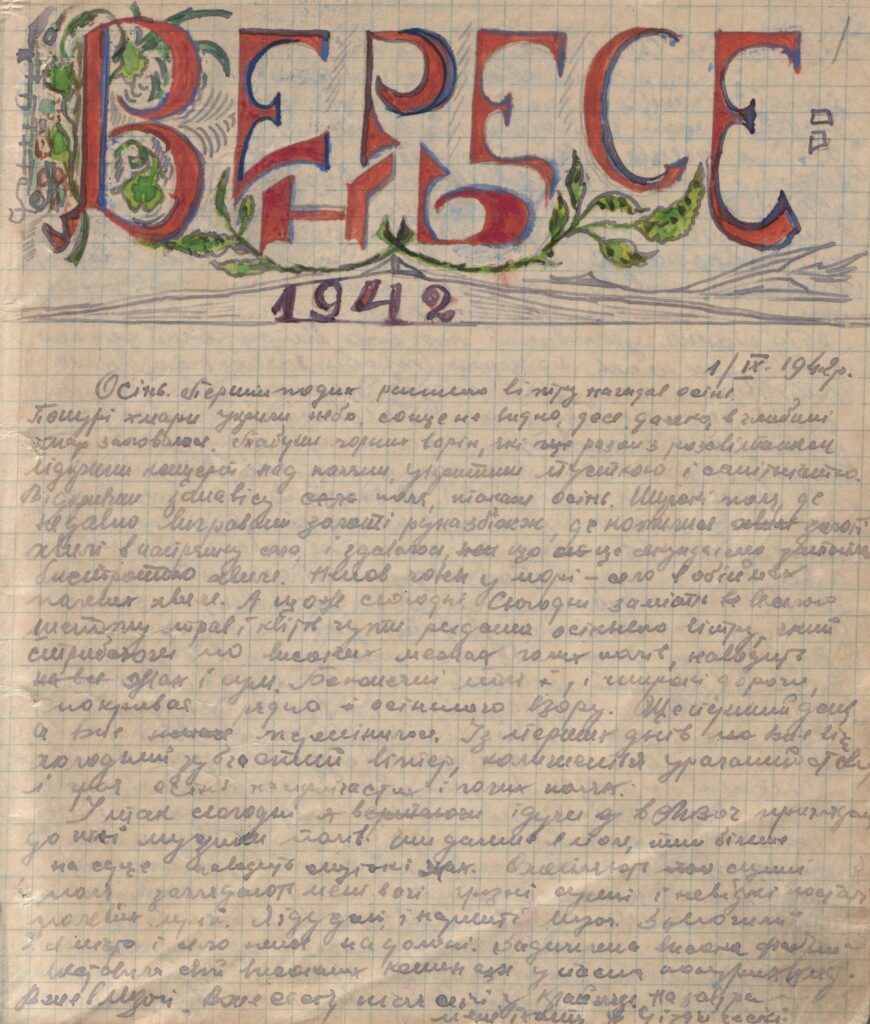

Because of this, primary sources played a key role in my research, in particular documents from the State Archive of Rivne Oblast. In addition to the files of the Extraordinary Commission, the “Diary of an Unknown OUN Member, a resident of Derman, on the Destruction of the Jews of Mizoch and the Uprising in the Local Ghetto” (1 September 1942 – 7 January 1943) proved particularly valuable (he is identified by modern researchers as Semen Lys).4 I was struck by the fact that the eyewitness not only praised the murder of Jews, but also documented how he became an accomplice in the crime. He saw a Jewish woman with a child and pointed her out to a Schutzmann, who shot her: “the smoke curled up over her head three times.”5

Another important source was the interviews I conducted with two eyewitnesses of the Mizoch tragedy in 2006, Mariia Moseichuk and Volodymyr Bidiuk, both Righteous Among the Nations. Unfortunately, these witnesses are no longer among us. In the end, this groundwork and source base would later, during my PhD, allow me to publish my first professional article on the Holocaust in Mizoch.6

Visualization of the Holocaust in Mizoch

In Holocaust historiography, Mizoch is most known for photographs of the shooting and the uprising in the local ghetto.7 According to various estimates, between 1,7008 and 3,7009 Jews perished here on 13-14 October 1942.

The photographs of the Mizoch shooting are widely known to the public. They are on display in many museums around the world and are freely available on the internet. I personally saw them at exhibitions in museums in the United States, Germany, and France. The German researcher Michaela Christ has noted that the photographs taken in Mizoch have long been part of the iconography of the Holocaust.10 They stand out from other well-known photos of mass shootings because they depict the victims as particularly vulnerable and defenseless. On four of the five photographs, it is clear that the victims are naked; on three of them, nearly all victims are without clothes. Their nudity is baffling. The women and children in the photos are helpless before the perpetrators. These pictures do not only demonstrate malicious acts but are themselves also part of the humiliation, arbitrariness, and disenfranchisement.11.

Today, the photographs are kept in the National Archives in Prague (Czech Republic).12 Copies are available on the official website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.13 For ethical reasons and out of respect for the victims, they must be published with particular care. Therefore, I will not publish these photos on this blog.

It is believed that the author of the photographs was a German gendarme, Gustav Hille, who photographed the action with the intention of preserving documentary evidence of these horrific events and using them if necessary. It is uncertain whether this is true.14 In 1944 or early 1945, Hille showed the photographs to his former employer, Heinrich Kunert, who resolved to give them to the Catholic Church. He showed the photos to the company’s lawyer, Dr. Alois Knötig, and through an intermediary they were sent to the papal secretariat in Rome. However, the images were returned with the message that the Holy See was already aware of similar incidents. Knötig kept the photos at home until they were confiscated. This is the official backstory of the photos of the Mizoch action. There are other versions in circulation. During my interview with a witness of the tragedy, Volodymyr Bidiuk, he said that there were more than five photos and that Gustav Hille had given him a film with 7 to 8 photos for safekeeping. However, Bidiuk, afraid of bearing such responsibility, destroyed them about a week later.15

There are also photographs of the victims taken during the Soviet commission’s investigation of the execution site on 27 November 1944. The ChGK report contains 4 images, whose originals are stored at the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF). According to a file of the Extraordinary State Commission, titled “On the Atrocities Committed by the Nazi Invaders…”, of 27 November 1944, the Germans forced the Jews to dig a pit 50 meters long, 7 meters wide, and 6 meters deep. The victims were then stripped naked, their property and valuables were taken away, and they were led into the pit in groups of 5 to 6 people. Among them were infants and elderly people. The killings were carried out with assault rifles and pistols shots in the head. The images of the victims are traumatizing, perhaps even more brutal than the ones described above. That is why I won’t publish them here. For scientific purposes, interested researchers can contact the author of the blog, or find them via the reference to GARF below.16

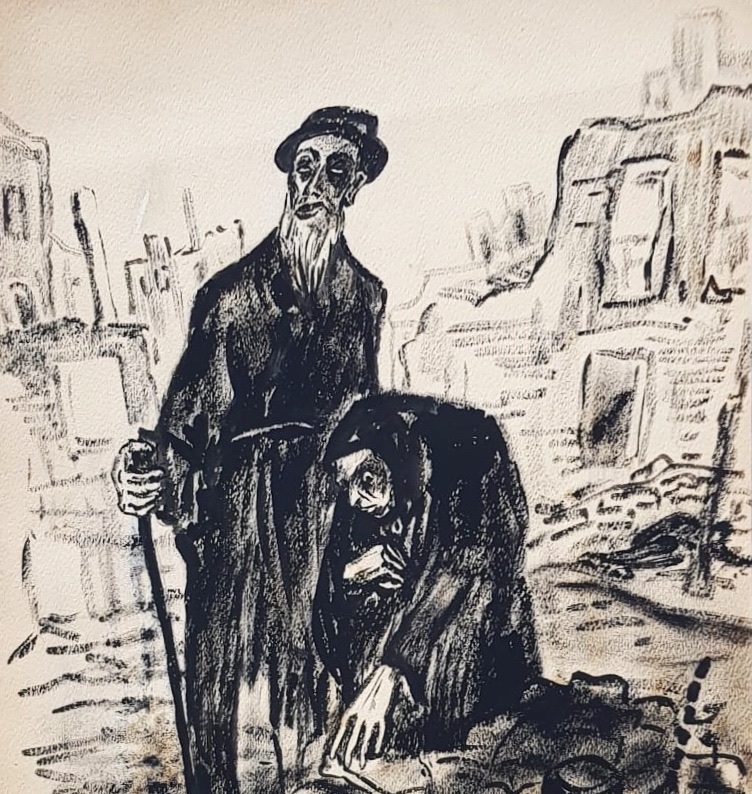

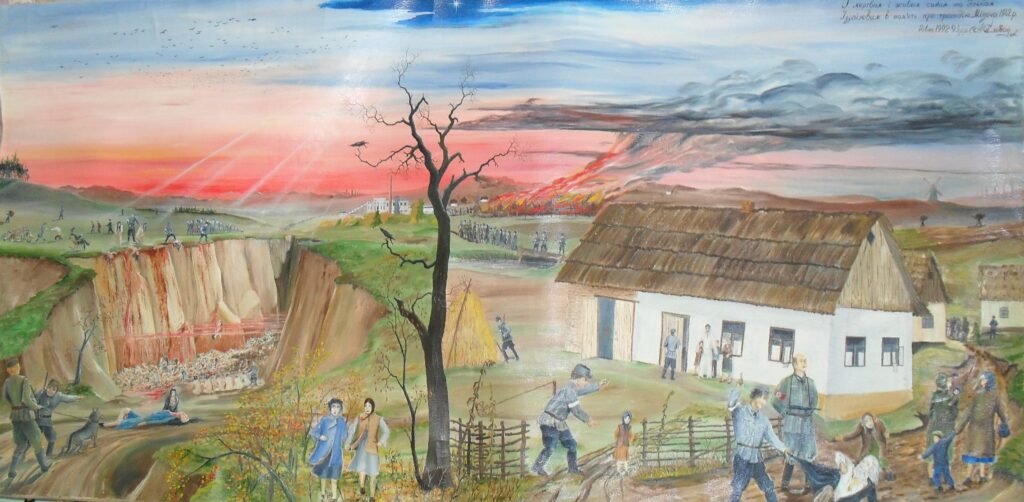

In addition to the original photos of the “action”, there exists a visualization of the catastrophe created in independent Ukraine. This is an artistic impression by Oleksiy Slobodiuk, painted in 1992 and titled “To the dead and living sons of Israel in memory of the 1942 Mizoch tragedy.” The author depicted the Shoah of the Jews of Mizoch after hearing the story of his aunt Mariia Moseichuk, a Righteous Among the Nations who saved a Jewish woman, Sofia Hornstein, in Mizoch. Despite the fact that the work is fictional, the painting accurately conveys the story of the plight of Mizoch Jews during the occupation. The painting depicts the pit where the mass shooting took place, the murder of Jewish individuals, dead victims, the fire in the ghetto that broke out during the uprising, a police search of the house of a Ukrainian family, the rescue of a Jewish woman, and more.

The Holocaust in Mizoch International Projects

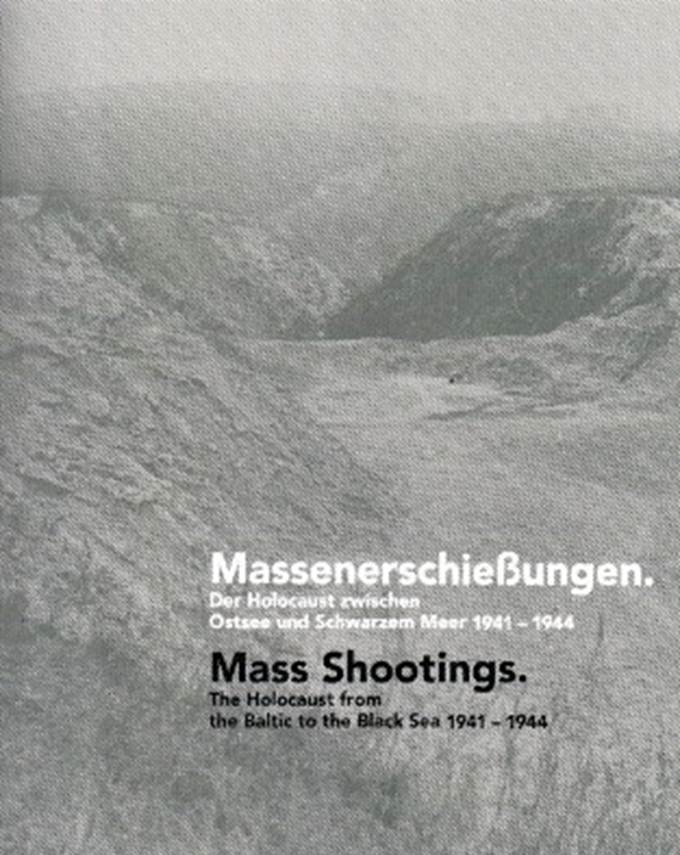

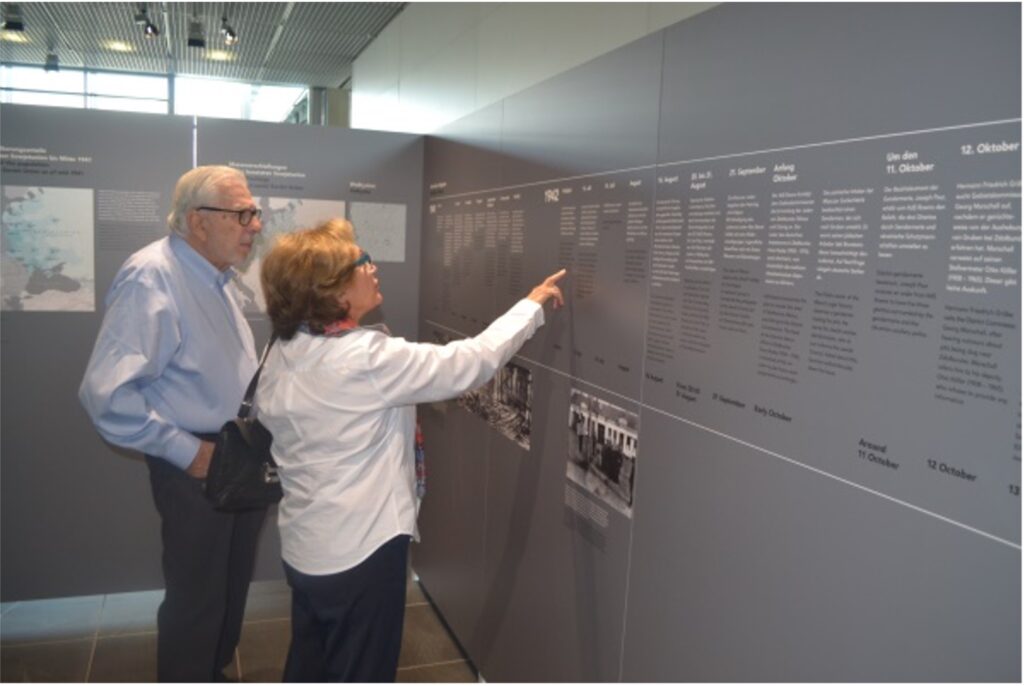

At an exhibition at the Topography of Terror17 in Berlin in September 2016, Mizoch was represented as a town that reflects the specifics of the mass murder of Jews in Eastern Europe, the “Holocaust by Bullets”. The exhibition was entitled “Mass Shootings. The Holocaust from the Baltic to the Black Sea 1941-1944”, and remains the most notable international project addressing the Holocaust in Mizoch18 for Western European audiences, where I had the honor of being on the advisory board. Reflections on the opening of the exhibition in Berlin are posted on my blog.19

The opening of the exhibition was attended by the then Minister for Foreign Affairs (and currently President) of the Bundesrepublik Frank-Walter Steinmeier.

In his speech Wounded Landscapes, Steinmeier addressed the tragedy of Mizoch and other settlements of the former Soviet Union, emphasizing the responsibility of German society for the memory of the Holocaust: “We, today’s Germany, cannot change what happened. But we must learn from history. We must assume the responsibility that our history imposes on us”.20

It is also important to mention that the collaboration between the documentation center and the Foundation Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe resulted in the publication of an exhibition catalog in English and German—and in 2021 a newly updated version of the catalog was published in Ukrainian and Belarusian.21 The catalog describes the systematic murder of Jews in the Soviet Union, and a separate section (pages 40-83) is devoted to the Holocaust in Mizoch. More than twenty scholars from different countries contributed to the catalog.

Another international project related to Holocaust remembrance in Mizoch was the project “Ethnic Conflicts, Forced Migrations, and Deportations in Volhynia, Eastern Galicia, and Bukovyna 1939-1949” by a Ukrainian-German group of students from the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv and the Ruhr University of Bochum.22

On 30 September 2016, this group of young researchers visited historical sites in Mizoch, including the Jewish and Polish cemeteries, the place where Jews were shot, monuments to World War II and Holocaust victims, and recorded video interviews with elderly residents. The stories of Neonila Pan’okha (born in 1929), Vira Poskrebysheva (1932), and Vasyl Pryshchepa (1931) dealt with the Holocaust in Mizoch in 1942, the Polish-Ukrainian confrontation in 1943, the consequences of the Sovietization of the region, etc.

Researchers from different countries have visited Mizoch in the framework of their own research projects. In December 2016, a German photographer and researcher of Jewish cemeteries, Christian Herrmann, visited the town to photograph sites of Jewish history (the shooting site, the Holocaust monument, the cemetery) and covered his trip in a blog post.23.

In the summer of 2017, Raisa Ostapenko, a Sorbonne University PhD student, interviewed Vasyl Pryschepa, a witness of the Holocaust in Mizoch, as part of her research on people who saved Jews. She recently published her research on this topic.24

Special publications play an important role in preserving the memory of the Holocaust. Laurence Broun, a descendant of Jews from Mizoch who currently lives in the United States, studied the story of his family and published a book in both English25 and Ukrainian26. Together with him, I was able to realize the translation of the Mizoch Memorial Book (Mizocz; sefer zikaron, 1961) from Hebrew into English27 and Ukrainian28. This book depicts the prewar life in the Volhynian shtetl, the Holocaust, and the postwar situation based on the memoirs of some sixty Jews. As far as I know, this is the only complete translation of a sefer zikaron memorial book into Ukrainian so far. The text is currently available in an electronic version, and we are looking for opportunities and sponsors to publish the book in print.

By the end of this year, the publication “Mizoch: the life and death of the Jewish community” will be published under my authorship, which will be implemented as part of the “Network of Memory”29 project with the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Germany30.

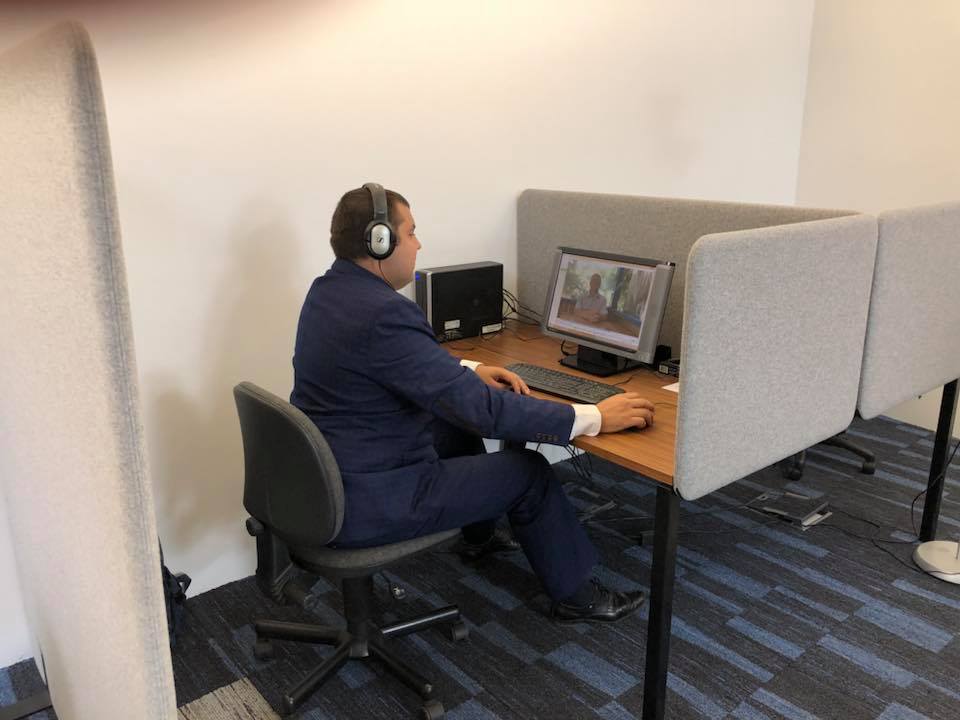

Academic institutions are also interested in the Holocaust in Mizoch. Since 1994, the Shoah Foundation’s Institute for Visual History and Education at the University of Southern California has been interviewing Holocaust survivors and rescuers. This collection contains sixteen video testimonies related to Mizoch in English, Ukrainian, Russian, Spanish, Portuguese, Czech, Polish, and Hebrew.31 The most informative of these are the testimonies of George Ganzberg, Claire Boren, Semen Velinger, Isaac Rozenblat, Me’ir Veltfroynd, and Mariia Moseichuk. They contain not only factual material about the catastrophe they experienced, but also reflections on and assessments of their own actions during the Holocaust and the trauma they suffered.

The French institution Yahad-In Unum (Paris) is doing the important work of documenting the crimes of National Socialism through the oral memoirs of non-Jews—and since 2022, the crimes of the Russian army in Ukraine too. In the winter of 2008, representatives of Yahad-In Unum explored the site of the Mizoch tragedy and recorded the video testimony of a witness of the shooting, Volodymyr Bidiuk. The value of the interview lies not only in Bidiuk’s recollections, but also in the fact that the witness pointed out the exact location where the victims were killed.32

In addition, an oral collection of non-Jewish memories of the Holocaust in Mizoch was created by the author of this blogpost in 2016 I interviewed about three dozen residents of Mizoch (all ethnic Ukrainians) about World War II and the Holocaust in Mizoch. The results of the oral history project have been published.33

Plans for Further Research on the Holocaust in Mizoch

Currently, I am working on a comprehensive monograph about the Holocaust in Mizoch, which will reflect the multidimensional palette of the “Holocaust by Bullets” in the western Volhynian town. In this project, I will try to investigate not only the murder of victims, but also the role of local civilians and neighbors in the genocidal process; to shine a light on various forms of discrimination, including sexual, religious, and psychological violence; the role of material gain in the Holocaust; and the reaction of Jews and non-Jews to the Shoah. The focus will be not only on the victims of the Holocaust, but also on local non-Jewish residents and their behavioral patterns. In Holocaust research, the position of non-Jews is traditionally defined with the triad perpetrators, observers, and rescuers. In real life, however, this division was rather arbitrary. Under certain circumstances, an observer could become a murderer or a perpetrator, and a perpetrator could become a rescuer, and vice versa.

Last year, my preparations for said monograph led me to publish my most fundamental articles on the Holocaust in Mizoch so far, although their total number reaches about two dozen. Among the most significant are five articles from 2022 and a monograph on the events of World War II and the first postwar decade in Mizoch (1939-1955).34 This is a study of the resistance and uprising in the Mizoch ghetto, which has remained a blank spot in Holocaust historiography, like the topic of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust in general. The other publications dealt with the situation of the Jews of Mizoch during the Holocaust, the antisemitism they encountered35, and their situation during segregation in the ghetto.36 the resistance of Mizoch jews during the Holocaust.37 The study of the role of economic factors in the Holocaust is also important. Evidence shows that material motivations were an incentive for the leadership and workers of state bodies, police officers, and local residents. The Jews suffered from this.38 The “solution to the Jewish question” in Mizoch, i.e. the extermination of the Jewish community in October 1942, is analyzed in a separate publication based on new sources.39

There are still issues that require separate consideration and analysis. For various reasons, including a lack of sources, they remain unexplored. Today, however, it is possible to research such topics at a sufficiently professional level, including psychological aspects of the Holocaust, the traumas suffered by victims, the stories of the killers, the latter’s motivation for cooperation with the enemy and collaboration, their postwar fates, and so on. Oral history sources and criminal files on convicted perpetrators in the security service archives make it possible to do this in a professional way.

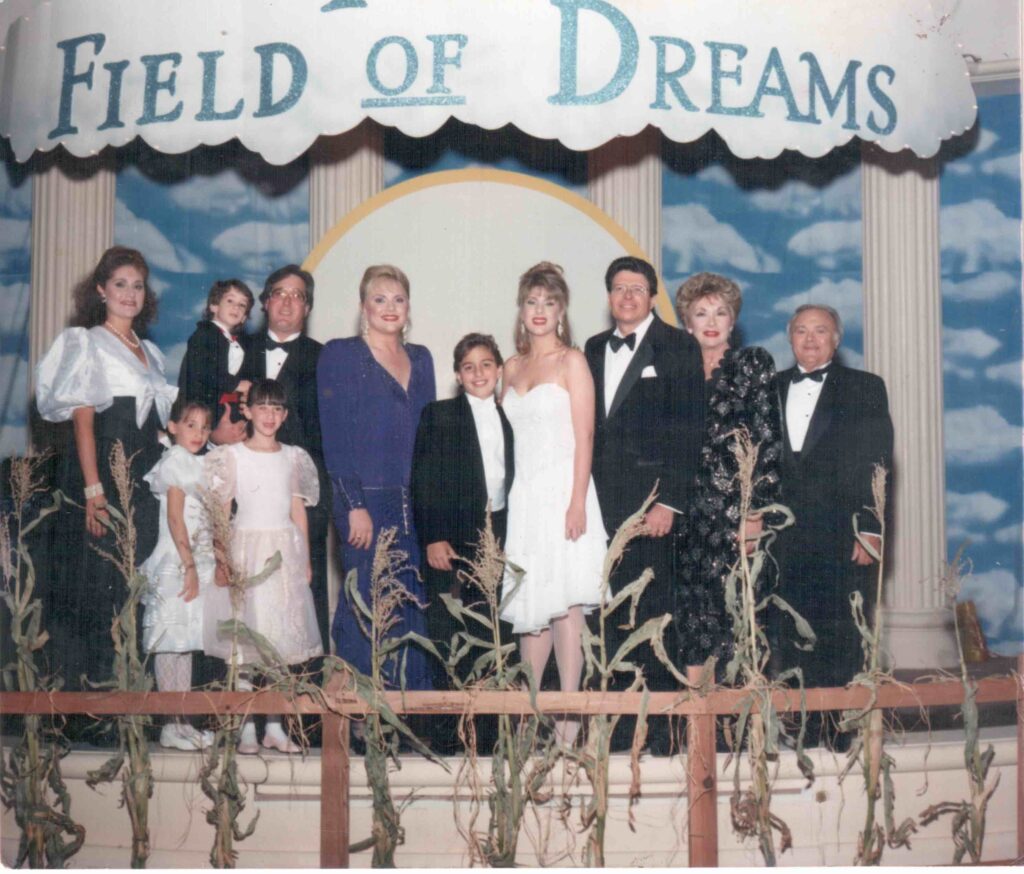

After the Shoah, many Jews were haunted by trauma. Me’ir Veltfroynd, who moved to Israel from Mizoch, noted: “I have dreams, I cannot forget what I experienced. Lately, now that I’m retired, I cannot forget, I scream at night. I cry at night, I take medication for my nerves. I am very nervous, I have anxiety from the Holocaust…”40 Isaac Rozenblat, who ended up in Argentina, refused to tell anyone about what he had experienced: “I never wanted to talk about what really happened in my life. It is very painful… I am in a state of extreme stress, thinking about what happened to my family and the people around us. ‘How can anyone who has not lived through it understand it?’”41. For George Ganzberg, who found himself in Boston, the trauma of the Holocaust manifested itself in the fact that he and his wife would not allow themselves to have children because they considered this a crime: “After all we’ve been through, why give birth only to condemn [a child] to the same grief?” It would take twelve years for them to have children, in 1956.42

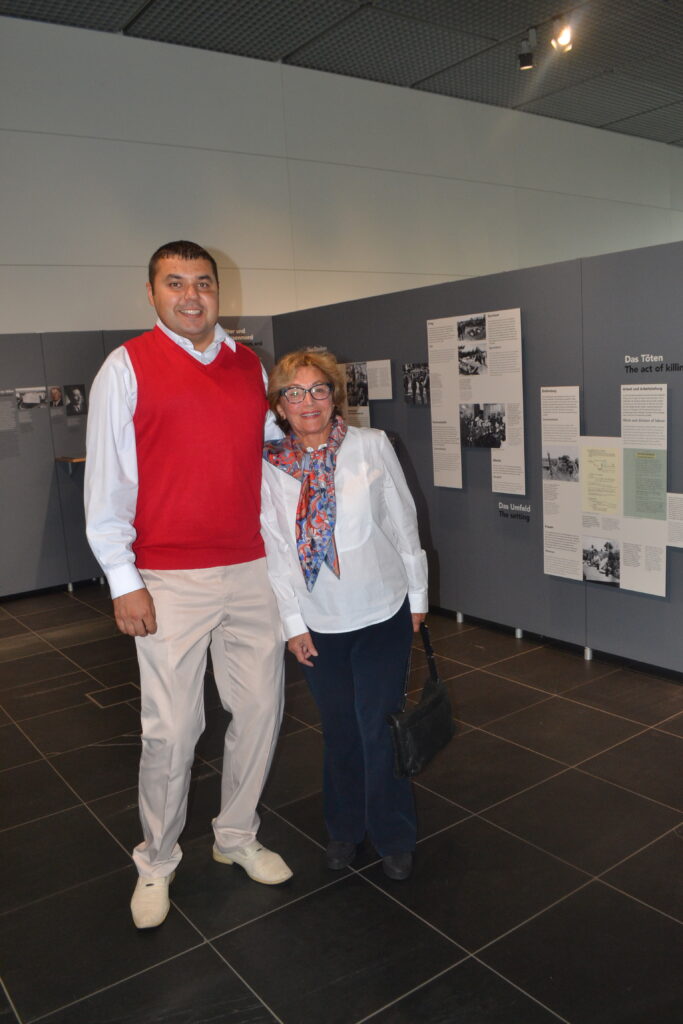

After the Holocaust, Claire Boren dedicated her life to working with survivors and their children, the second generation. In 1975, she attended a conference on the second generation in New York, which was an awakening of sorts. In 2016, Boren attended the opening of the exhibition about Mizoch at the Topography of Terror in Berlin. Nowadays, she is engaged in art (watercolor painting).43 As a professional artist, she has revived her memories of the experience through abstract artwork. Boren exhibits her work and shares her testimony about the Holocaust during seminars.

Another unexplored issue is the motives behind the behavior of perpetrators at the local level—of those who executed the Mizoch tragedy. In this regard, criminal files on convicted Mizoch policemen from the archives of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) play a key role. Most of the Holocaust perpetrators in Mizoch were never punished. In 1963-1964, trials of German gendarmerie officials were held in Nuremberg-Fürst. Joseph Paur and Wilhelm Wacker were convicted for participation in the liquidation of the ghettos in Zdolbuniv, Mizoch, and Ostroh. Paur received seven years in prison, and Wacker was sentenced to three years.44 In the 1940s, the Soviet authorities convicted local collaborators. In the sentences of the Mizoch police officers, there were frequent references to their security functions and escorting victims to the place of execution. For example, Oleksii Lomynskyi, who was transferred from Ostroh to Mizoch in 1942, admitted that he had “taken part in the mass extermination of Soviet citizens of Jewish ethnicity, participated together with other policemen in the arrest and escort of Soviet citizens of Jewish ethnicity to the shooting site, where the Germans carried out the shooting”.45 Similar testimonies are contained in the files of Adam Prokopchuk46 and Mykhailo Fryziuk,47 who initially served in the Derman police and, in the fall of 1942, participated in the guarding and escorting of Jews to the shooting site in Mizoch. The latter noted that after escorting the convoy of Jews to the sugar factory, he returned to the police station and learned about the shooting of the victims from his colleagues.48

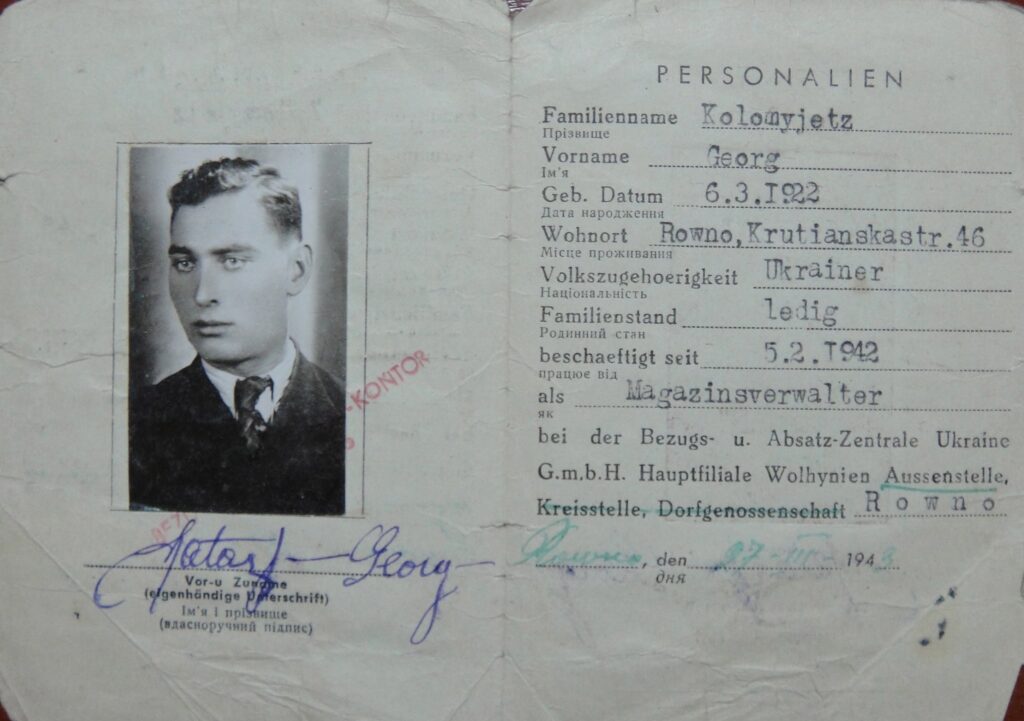

However, police officers were involved in other crimes. Heorhii Kolomiiets was involved in a wide range of crimes. At the beginning of the occupation, he was involved in a pogrom with Jewish victims. He repeatedly robbed and beat Jews, for which he was nicknamed the “butcher” (kat).49 Kolomiiets was in charge of the selection of informers who would identify families whose property was in turn confiscated. There were also cases of moral and sexual abuse of victims. Kolomiiets forced Jews to dance while they prayed, after which one of the old men had his beard cut off and was locked up in a dungeon.50 Together with a colleague Kolomiiets raped a Jewish woman.51

In January 1945, Heorhii Kolomiiets was sentenced to death by firing squad. A month later, this sentence was commuted to hard labor for up to 20 years, but he did not serve out his sentence, because in December 1946 he died.52

Other policemen who committed crimes against the Jews of Mizoch included Volodymyr Vinohrodskyi. In July 1941, he joined the Mizoch district police, he served as a commandant and received a salary of 550 rubles. He was involved in the mass murder of Jews in Mizoch and convoyed them to the shooting. Before the mass murder of the Jewish community, he shot a man named Moter Mizoch.53 Witness Zofia Filipets noted that Vinohrodskyi conducted searches of apartments, looking for Jews. To save her own life and the lives of the Jews she was hiding, Filipets gave Vynohrodskyi vodka, and he left her house.54 In January 1945, he was sentenced to death by firing squad, but the sentence was commuted to 20 years of arrest, of which he served 11 years, 4 months, and 25 days.55

Remembrance of the Holocaust and the Present

In order to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust, memorial events are traditionally held in Mizoch twice a year: on 13-14 October (the day of the mass murder) and 27 January (International Holocaust Remembrance Day) at the Holocaust memorial. The monument is located about 300 meters from the location where the Jews were shot. The shooting site itself is not marked with memorial plaques or signs, it is surrounded by agricultural land.

It is generally assumed that the monument in Mizoch was built in the early 1990s. This is also stated in reference books.56 However, according to at least one witness, the monument was erected in May 1989.57 The project was initiated by the management of the Mizoch sugar factory and the Mizoch village council.58

Clearly, the perestroika period affected the inscription on the monument, which departed from Soviet clichés. Instead of the usual “Soviet civilians”, the inscription, “Eternal memory of the people of Jewish descent shot by the fascists in 1942”, points to the Jews as victims of the Tragedy. This wording existed until the summer of 2012, when, after the monument was restored, the inscription was replaced with a more concise one: “In memory of the victims of the Holocaust of 1942”.

The monument is a stele of about 6 meters high. In its original form, it featured a plaster image of a half-naked Jewish family (man, woman, child). The woman (mother) held the child in her arms, the man was lying down (apparently wounded). The figures, made of plaster, were damaged over time (crumbled). In 2012, the family’s appearance changed. Since then, the Jewish man stands in the foreground in the pose of the family’s protector. The woman and child are behind him.

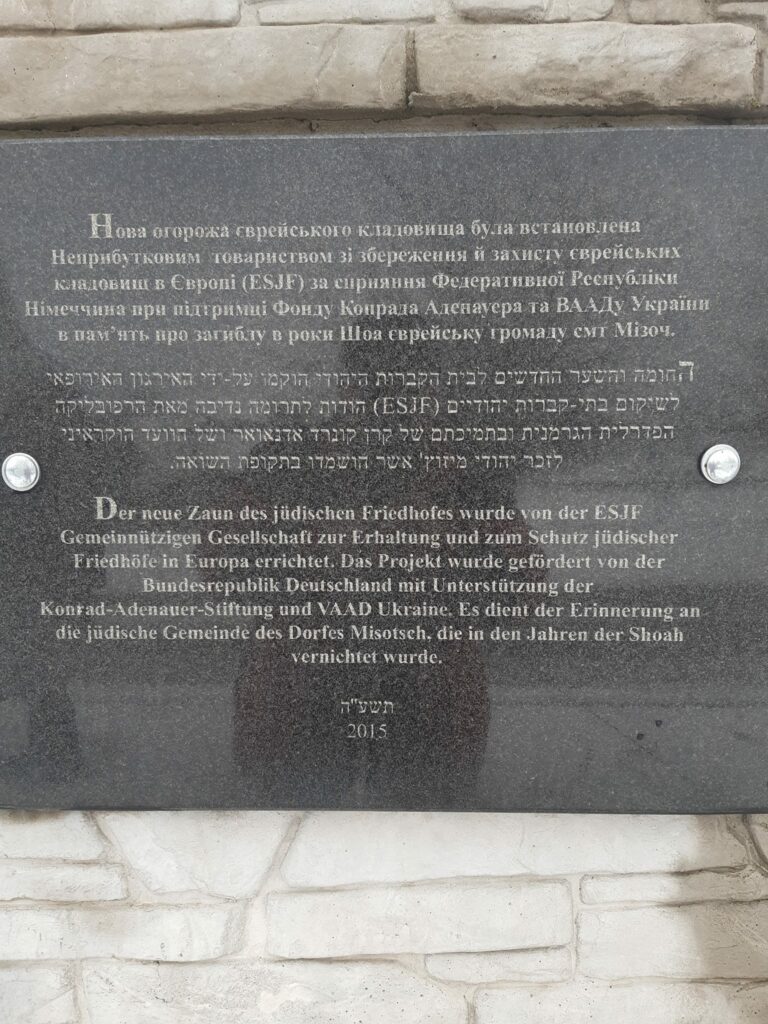

The Jewish historical and cultural monuments in Mizoch include the Jewish cemetery, which unfortunately served as a pasture until 2015. In 2015 thanks to an international project, the area was fenced off and a plaque was put up, which reads: “The new fence of the Jewish cemetery was installed by the nonprofit organization for the preservation and protection of the Jewish community in Europe (ESJF) with the assistance of the Federal Republic of Germany and the support of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and the Association of Jewish Organizations and Communities in Ukraine, in memory of the Jewish community of Mizoch village who perished during the Shoah”.

In 2019, volunteers returned a matzevahs found in the Mizoch Park to the cemetery. According to some reports, during the German occupation, matzevahs from the cemetery were used to pave pathways in the park.

Descendants of the survivors of the Mizoch Shoah began visiting Mizoch in the late 1980s and 1990s. According to witnesses, the first visit was in 1986.59

Subsequently, on the 50th anniversary of the tragedy in 1992, a delegation of Jews from South Africa, Israel, and the United States came to Mizoch.60 In early August 1992, the newspaper Nove Zhyttia reported on their visit to Mizoch as follows: “Jews from Israel and the United States came to worship the ashes of their dead ancestors. They followed the path that their parents followed in 1942… Guests from the United States and Israel prayed, scattered earth around a monument which they brought with them from Israel. Rabbi Yonah Guler unveiled a memorial plaque installed on the memorial stele. The plaque was made by the descendants of murdered Jews”.61

At the same occasion, guests from Israel visited rescuer Mariia Moseichuk. In an interview with the newspaper, the rescued Jew Leon Perl noted that it was the first time in 50 years that he had visited his native land: “I feel well in America, I could forget everything, but how can you forget… As long as I able to, I will visit this place. And if I can’t, I have strictly ordered my children to come here.62

Since the mournful 70th anniversary of the tragedy, in 2012, the process of memorializing the victims of the Holocaust in Mizoch has intensified.63 The events planned for the 80th anniversary of the tragedy in 2022 could not be realized due to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In 2019, Holocaust survivor Assia Raberman visited Mizoch.64 Today, 94-year-old Assia Raberman has dedicated her life to the TOLI educational programs. In cooperation with The Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights, she gives lectures to teachers in Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Greece, Italy, and the United States. In 2019, she participated in a seminar on the Holocaust for teachers in Lithuania.65

As recently as November 2022, she was scheduled to speak at a seminar on the Holocaust and human rights organized by TOLI and the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies.66 In 2021, I interviewed her about the Holocaust in Mizoch.67 Since 2020, the Mizoch community initiative has been cooperating in the Connecting Memory project.68 In April 2021, a non-invasive examination of the area where the Jews were allegedly buried in 1942 took place. Further cooperation plans include the installation and maintenance of memorial signs, and the publication of an English-language study of the Jewish community and the Holocaust в Mizoch in mid-2023.

Holocaust Research in Ukraine

In this short entry, I cannot avoid the issue of Holocaust studies in contemporary Ukraine. I should note that in Ukraine, Holocaust scholars are often confronted by the stereotype that their interest in the topic comes from Jewish roots. I have been asked on many separate occasions if I was Jewish and why I was researching the Holocaust and not the Holodomor. Although in reality most professional Holocaust scholars in Ukraine are ethnic Ukrainians.

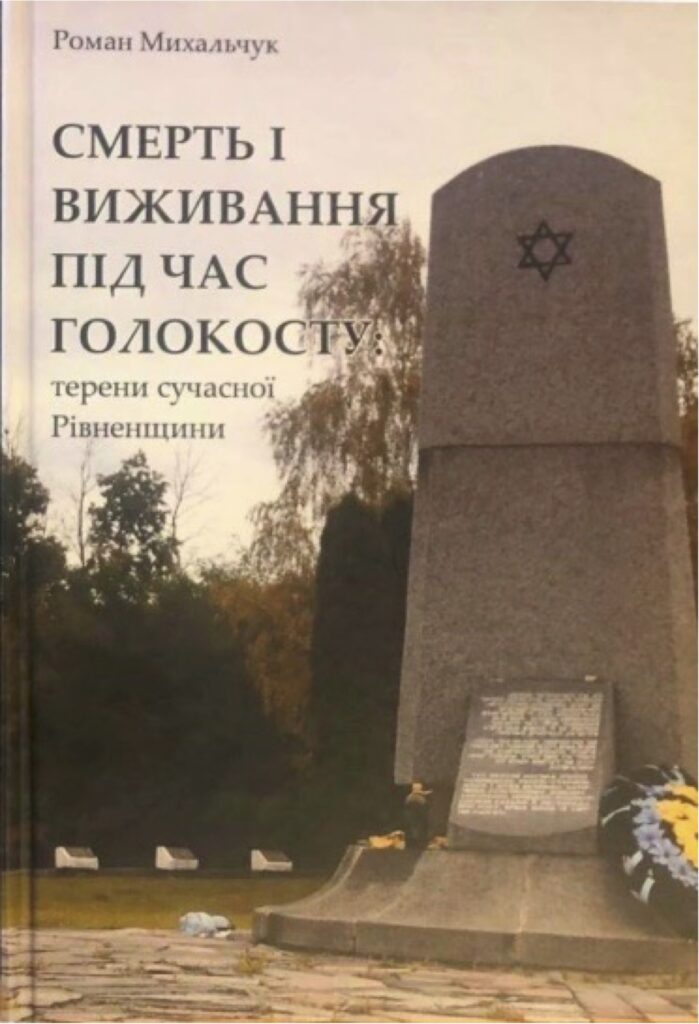

Unfortunately, in the city of Rivne and Rivne Oblast, where I live and work, Holocaust scholars can be counted on the fingers of one hand. However, what matters here is quality, not quantity. Professor Maksym Hon, who is now defending Ukraine in the Ukrainian army against the Russian occupiers,69 has authored a collection of Holocaust-related documentation for Rivne Oblast70 and a handbook on genocide studies.71 Thanks to the NGO Mnemonics, which he heads with co-founders Petro Dolhanov and Nataliia Ivchyk, Stolpersteine were installed in Rivne (2018)72, as well as a monument to the prisoners of the Rivne ghetto (2019)73, and more. In November 2022, this organization received an award from the Munich Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism.74

The development of Holocaust studies in Ukraine is unmistakably showing positive trends. There is a formal date, the year 1996, that marks a milestone in the development of Holocaust studies in Ukraine—this was the defense of the first dissertation in Ukraine on the Nazi genocide against the Jews of Ukraine (1941-1944) by Anatolii Podolskyi. Since then, over a quarter of a century, there have been improvements in the field—meanwhile, more than 20 dissertations on the Holocaust have been defended.

I will allow myself to disagree with the assessment of my colleague Alexander Kruglov, who noted that the prospects for the development of Holocaust studies today are “not very bright,” according his subsequent argumentation.75 Such an assessment would have been fair when talking about the state of research in the 2000s, but not today. I recall the feedback I received when I chose the Holocaust as the topic of my dissertation in graduate school back in 2010. At the time, I was pointed to possible difficulties related to the rather weak development of Holocaust studies in Ukraine. However, as of 2023, the situation has altered substantially: a stable circle of researchers has emerged in Ukraine for whom the Holocaust is a professional topic of research.

The biggest improvements in Ukrainian Holocaust historiography, and public history in this area, have become noticeable over the past five years. We have seen a number of publications by Ukrainian scholars in international professional journals and the integration of researchers into Western academia. The assessment is even more impressive when compared to our neighbors, Russia and Belarus, where totalitarian regimes make such research de facto impossible.

Young Ukrainian scholars, free from stereotypes and preconceptions, are taking on controversial topics that are sensitive in society. The issues of collaborationism and the role of the Ukrainian police in “solving the Jewish question” are discussed in their works (Yuriy Radchenko, Andii Usach, Roman Shliakhtych, Daniil Sytnyk, and Tetiana Borodina). The range of issues addressed by scholars has significantly expanded, including gender history of the Holocaust (Marta Havryshko, Nataliia Ivchyk), the issue of bystander ambiguity, microhistory and local studies, and cases of specific individuals (genocide perpetrators). A young generation of scientists is gradually crystallizing, which forms the core of Ukrainian historiography. Evidence of this is the recent issue of the leading Ukrainian magazine “Ukraina Moderna”, No. 34, 2023, dedicated to the Holocaust: “The Holocaust in Ukraine: how the history of a crime is (not) written”.

From year to year, there is an increase in the number of venues in Ukraine where controversial issues of Holocaust history are discussed (from Lviv and Rivne to Kyiv and Kharkiv, etc.), and where academic and public events, seminars, and other activities are organized. Such platforms include academic discussions and conferences organized by the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies, headed by Anatolii Podolskyi (Kyiv)76; the Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies TKUMA, headed by Ihor Shchupak (Dnipro)77; the Center for the Study of Interethnic Relations in Eastern Europe, headed by Yurii Radchenko (Kharkiv)78; and the NGO Mnemonics, headed by Maksym Hon (Rivne)79. The NGO After the Silence, headed by Andrii Usach (Lviv), develops projects in the field of memory culture and public history of anthropology. More than 100 oral history interviews about the Second World War, the Holocaust, Soviet repressions, etc. can be found in the organization’s archive.80 Another contribution to the understanding of the Holocaust comes from a series of seminars with leading international Holocaust scholars, “Overcoming the Past,” conducted in the format of interviews on the website of Ukraina Moderna.81

Ukrainian researchers are active as consultants and co-authors of documentary films about the Holocaust (Ihor Shchupak, Maksym Hon, Andrii Usach, Yurii Kaparulin, Roman Mykhalchuk, and others).82 The above activities move beyond the scientific realm into the realm of public history, which contributes to the preservation of the memory of the Holocaust in Ukrainian society.

The fact that Ukrainian Holocaust scholars are invited to teach their own courses as guest lecturers at American and European academic institutions attests to the level of their work.

There are certain features that have a positive impact on Holocaust studies in Ukraine. In Dnipro, there is the TKUMA Institute, which publishes a peer-reviewed journal, Holocaust History Problems: Ukrainian Dimension. Since 2020, this journal has acquired the status of a professional publication in Ukraine, which is an important factor for lecturers working in higher education institutions. Until recently, the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies in Kyiv also published a specialized journal, Holocaust and Modernity, which published articles by Ukrainian and foreign researchers. Publications in both journals are free of charge and require an appropriate level of expertise, which is reflected in the high level of research. At the same time, both centers focus more on educational activities, as most of their projects are intended for teachers and school students.

Another strategy for supporting Holocaust studies is pursued by the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mendel Center for Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. The program manager is Natalya Lazar. This project is designed for scholars rather than for educators. Since 2016 the USHMM has been organizing seminar schools in Kyiv for Holocaust scholars and those who intend to work in the field. Russia’s attack on Ukraine in 2022 necessitated adjustments: in the course of 2022-2023 a special virtual program has been developed to support Ukrainian scholars in implementing their projects based on the sources of the USHMM. Now, at a time of extremes, such support (moral and material) is of particular value for Ukrainians. Every year, the school’s graduates have the opportunity to visit Washington, DC. Over the past decade, more and more Ukrainian researchers have taken advantage of this opportunity.

It should also be noted that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has influenced the attitude of Western institutions towards Ukrainian researchers, which have begun to offer more opportunities for research programs to Ukrainians, supported by grants and fellowships (both residential and remote).

I have confidence in the upward development of Holocaust studies in Ukraine. There is every reason for this. And victory over the enemy in a peaceful country will only contribute to this process.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Tobias Wals

- Rivne Oblast State Archive (DARO), f. R-534, op. 1, spr. 3, ark. 196. ↩

- A.V. Mialovyts’kyi et al., eds., Istoriia mist i sil Ukraïns’koï RSR u 26 t.: Rovens’ka oblast’ (Kyiv: Academy of Sciences of the URSR), 325. ↩

- Iu. Los’, “Ïkh nikoly ne zabuty,” Chervonyi prapor, 17 February 1962. ↩

- DARO, f. R-30, op. 2, spr. 83, ark. 40. ↩

- DARO, f. R-30, op. 2, spr. 83, ark. 11. ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk, “Trahediia mizots’kykh ievreïv v konteksti Holokostu na Rivnenshchyni,” Slov’ians’kyi visnyk: zb. nauk. prats’ Rivnens’koho instytutu slov’ianoznavstva Kyïvs’koho slavistychnoho institutu, Seriia “Istorychni ta politychni nauku”, vyp. 11, 2011, 96–100. ↩

- For more details about the uprising in the Mizoch ghetto, see Mykhalchuk R. “I wanted revenge for the shed innocent jewish blood”: The resistance of Mizoch jews during the Holocaust. Eminak. № 4 (40), (2022), 236–253. ↩

- I. Al’tman et al., Kholokost na territorii SSSR: entsiklopediia, 2nd edition. (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2011), 587. ↩

- State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF), f.-7021, op. 71, spr. 59, л. 6; DARO, f. R-534, op. 1, spr. 3, ark. 196-196v. ↩

- M. Krist, “Svitlyny, shcho mistiat’ nasyl’stvo. Demonstratsiia i perehliad zobrazhen’ zhorstokosti ta strazhdan’, Masovi rozstrily. Holokost vid Baltiis’koho do Chornoho moria, 1941-1944 (Kyiv: Huss, 2021), 314. ↩

- M. Krist, “Svitlyny, shcho mistiat’ nasyl’stvo. Demonstratsiia i perehliad zobrazhen’ zhorstokosti ta strazhdan’, Masovi rozstrily. Holokost vid Baltiis’koho do Chornoho moria, 1941-1944 (Kyiv: Huss, 2021), 318. ↩

- Národní archiv, Prag, ČVKSNVZ, Az. 338/75, Fotograf: Gustav Hille; Masovi rozstrily, 80. ↩

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum arkhiv. Photograph Number: 17876, 17877, 17878, 17879. ↩

- Masovi rozstrily, 76. ↩

- Interview with Volodymyr Bidiuk, 8 July 2006, Archive of Roman Mykhalchuk. ↩

- GARF, f. 7021, op. 71, spr. 59. ↩

- See R. Mykhalchuk, “Pam’iat’ pro podolannia mynuloho u Mizochi: rozdumu pro ukraïns’ki ta zakornonni komemoratyvni praktyky,” Ukraïna Moderna, 16 October 2016, https://uamoderna.com/event/mykhalchuk-memory-about-holocaust. ↩

- The story of Mizoch is told using photographs from the interwar period of the 1920s and 1930s, which depict the multicultural coexistence of Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews. In stark contrast are the subsequent stands that highlight the liquidation of the Jewish community. In order not to shock visitors too much, the photographs of the executions are somewhat reduced in size compared to other images. A bright page in the history of the Holocaust is the rescue of Jews by Righteous Among the Nations. The exhibition presents photos of the Slobodiuk family, who are officially recognized as Righteous, although more people saved victims of the Mizoch Shoah. The text of the exhibition catalog contains a chronology of the murder of the Mizoch Jews, including the pogrom, resettlement in the ghetto, and the shooting of Jews in a ravine. The opening of the exhibition was attended by Claire Boren, a rescued Jew from Mizoch who now lives in the United States. Her story of rescue and survival is available to the public at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVml2_uGiiw. ↩

- See Mykhalchuk, “Pam’iat’ pro podolannia mynuloho u Mizochi,” Ukraïna Moderna. ↩

- Frank-Walter Steinmeier, “Poraneni landshafty,” Dzerkalo tyzhnia, 30 September 2016, https://zn.ua/ukr/columnists/poraneni-landshafti-220301_.html. ↩

- Masovi rozstrily. ↩

- See Mykhalchuk, “Pam’iat’ pro podolannia mynuloho u Mizochi,”Ukraïna Moderna. ↩

- Herrmann Christian, “Mizoch and the emptiness,” https://vanishedworld.blog/2016/12/. ↩

- R. Ostapenko, “Beyond the Underdog Mentality: PhiloSemitism amongst Protestant Rescuers in Wartime Ukraine,” Harvard Theological Review, Volume 115 , Issue 4 , October 2022 ,538-565. ↩

- L. Broun, Echos from Mizocz: A shtetl lost (Washington, DC: self-published, 2020). ↩

- L. Broun, Vidlunnia z Mizocha: znyklyi shtetl, translater from the English by D. Alad’ka (Rivne: Format-A, 2020). ↩

- The English original of the book can be accessed online at https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/Mizoch/Mizoch.html. ↩

- The Ukrainian translation can be accessed online at https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/Mizoch/Mizochu.html?fbclid=IwAR2fLoeyfMLVcoehv1XHSoX7CKIjiB9BO8qPygrM2cQE5iQBaj_EmX3unRI#TOC. ↩

- This publication is part of the “Connecting memory” project series of studies conducted and published in 2022-2023, during the phase of Russia’s full-scale invasion against Ukraine. These publications show both local features and common features of the Holocaust in different Ukrainian communities. Information about the project: URL: https://netzwerk-erinnerung.de/en/project/ ↩

- Mizoch: zhyttia ta zahybel yevreiskoi hromady / Roman Mykhalchuk. — Kyiv: Ukrainskyi tsentr vyvchennia istorii Holokostu, 2023. ↩

- Visual History Archive (VHA) 38193, Mariia Moseichuk (Ukrainian). VHA 38669, Nikolai Slobodiuk (Ukrainian). VHA 46431, George Ganzberg (English). VHA 18572, Clare Boren (English). VHA 7722, Emil Goldbarten (English). VHA 17845, Rachel Mosse (English). VHA 52998, Jozeph Likwornik (English). VHA 37515, Igor’ Avanov (Russian). VHA 38542, Elizaveta Palamarchuk (Russian). VHA 44509, Semen Velinger (Russian). VHA 38507, Isaac Rozenblat (Spanish). VHA 35066, Bunia Finkiel (Portuguese). VHA 20499, Ema Altrichterova (Czech). VHA 47229, Jozef Stos (Polish). VHA 49034, Rivah Bregnan (Hebrew). VHA 38537, Me’ir Veltfroynd (Hebrew). ↩

- Yahad-In Unum, testimony 574U. ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk, “Novi svidchennia pro Holokost v Mizochi (za rezul’tatamy usnostorychnoho proiektu u lypni-serpni 2016 r.),” Aktual’ni problemy vitchyznianoï ta vsesvitn’oï istoriï: nauk. zapysky RDHU, vyp. 29, 2017, 265-274. ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk, Mizoch: trahichni storinky istoriï. 1939-1955, 2nd revised edition (Kyiv: Kondor, 2022). ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk, “‘Ia buv hirshe nizh sobaka i ves’ chas pytav chomu tak’: stanovyshche ievreïv v Mizochi pid chas Holokostu,” Problemy istoriï Holokostu: ukraïns’kyi vymir. Referovanyi shchorichnyi zhurnal, vyp. 14, (2022), 58-100. ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk, “Stanovyshche ievreïv v Mizots’komu hetto,” Zaporizhzhia Historical Review, vyp. 6 (58), (2022), 209–229. ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk, “‘I wanted revenge for the shed innocent jewish blood’: The resistance of Mizoch jews during the Holocaust,” Eminak, № 4 (40), (2022), 236–253. ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk and P. Dolhanov, “‘Ievreiu, my tebe zdamo, nam potriben tvii odiah’: pohrabuvannia ievreïv Mizocha pid chas Holokostu,” 34, Ukraïna Moderna, (2022), 141-196. ↩

- R. Mykhalchuk, “Henotsyd ievreïv Zakhidnoï Volyni na prykladi mistechka Mizoch v 1942 r.,” Intermarum: istoriia, polityka, kul’tura, vyp. 11, (2022), 67-82. ↩

- USC SFI VHA 38537, Me’ir Veltfroynd. ↩

- USC SFI VHA 38507, Isaac Rozenblat. ↩

- USC SFI VHA 46431, George Ganzberg. ↩

- Moie mystetstvo: vidnovlennia moieï pam’iati pro Holokost, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YA5tRQ1QlRM. ↩

- M. Dean, ed., Encyclopedia of camps and ghettos, 1933-1945 : Vol. 2, Pt. B, Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 1428. ↩

- Rivne Oblast SBU Archive (AU SBU RO), spr. 10230. Т. 1, ark. 299-300. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 8566, ark. 347. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 10230. Т. 1, ark. 79. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 10230. Т. 1, ark. 80-81. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 3444, ark. 66v. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 3444, ark. 85. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 3444, ark. 84v. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 3444, ark. 124. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 12463, ark. 10. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 12463, ark. 13v. ↩

- AU SBU RO, spr. 12463, ark. 55. ↩

- I. Al’tman et al., eds., Kholokost na territorii SSSR: entsiklopediia, 2nd edition. (Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2011), 587. ↩

- Interview with Volodymyr Tesliuk, 22 April 2016, Archive of Roman Mykhalchuk. ↩

- Interview with Volodymyr Tesliuk, Archive of Roman Mykhalchuk. ↩

- Interview with Raïsa Volos, 13 August 2016, Archive of Roman Mykhalchuk. ↩

- Ie. Shylan and M. Ohorodnyk, “Po shliakhu smerti cherez 50 rokiv,” Nove Zhyttia, 12 August 1992. ↩

- Shylan and Ohorodnyk, “Po shliakhu smerti,” Nove Zhyttia. ↩

- Shylan and Ohorodnyk, “Po shliakhu smerti,” Nove Zhyttia. ↩

- The executive committee of the Mizoch Village Council responded to the 70th anniversary according to an application submitted by the village’s residents. The events were to be held according to the resolution “On consideration of the application of R. Iu. Mykhalchuk, resident of the village of Mizoch, on the reconstruction of the monument to the perished Jews of 1942″ (registered no. 2/17-M-6 on 10 January 2012). The following events were developed (subsequently published in the newspaper Visnyk Mizocha). The events provided for the preparation of documents for allocation of a land plot for the placement of a monument to citizens of Jewish ethnicity who perished in 1942, at the site of their mass extermination on Sosonky Street in the village of Mizoch; the preparation of a “passport” for the monument; embellishment of the site surrounding the memorial; restoration of the monument, together with the Rivne Oblast Charity Foundation Hesed Osher; a memorial meeting on 12 October 2012 to commemorate the Jews killed in October 1942; coverage of the phenomenon of genocide against Jewish citizens on the territory of Mizoch in the Visnyk Mizocha; and memorial services in the churches of the village for the innocent victims of Jewish ethnicity. The financial costs of the reconstruction of the monument were borne by the Honorary Citizen of the village of Mizoch. of the village of Mizoch Oleksandr Andriyuk. “U pam’iati nazavzhdy,” Visnyk Mizocha, information brochure of the Mizoch village council, 2012, 1. ↩

- The story of Assia: a Holocaust survivors visits her native town in Ukraine, https://vimeo.com/425838656. ↩

- Assia Raberman, who survived the Holocaust, in conversation with teachers in Lithuania, https://vimeo.com/656548410. ↩

- For more details about the seminar, see https://www.holocaust.kiev.ua/News/details/ivsem_vchmin_2022. ↩

- Letter from Assia Raberman to Roman Mykhalchuk, 14 December 2021, Archive of Roman Mykhalchuk. ↩

- More about the project: https://netzwerk-erinnerung.de/uk/. ↩

- “This Jewish Ukrainian professor could still be teaching. He chose to go to war instead,” Forward, 4 August 2022, https://forward.com/news/513172/jewish-ukrainian-professor-war/?fbclid=IwAR0mWPdMMAf3OF5KMP5SXT0cIKwQMWtXM1XPk41KK5KfnB1OFZQQT0BTg-g. ↩

- M. Hon, eds., Holokost na Rivnenshchyni: dokumenty i materialy, (Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia: Tkuma and Prem’ier, 2004). ↩

- M. Hon, Henotsydy pershoï polovyny XX stolitta: porivnial’nyi analiz: navch. posib. dlia stud. istor. Spets. vyshchykh navch. zakladiv (Ivano-Frankivsk: Lileia-NV, 2009). ↩

- V. Odarchenko, “‘Kameni spotykannia’: imena p’iaty zhertv natsyzmy vidnyni vkarbovani v brukivku Rivnoho,” Radio Svoboda, 27 July 2018, https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/29393481.html. ↩

- I. Marchuk, “U Rivnomu vidkryly pam’iatnyi znak zhertvam hetto,” Suspilne, 13 December 2019, https://suspilne.media/4645-u-rivnomu-vidkrili-pamatnij-znak-zertvam-getto/ ↩

- The nsdocu prize is awarded since 2018 for contributions to the conservation of memory of Nazi terror. The first prize was awarded to the book “Anne Frank”, the second one to the Camp des Milles memorial in France, the third one to Mnemonics (Rivne, Ukraine). ↩

- A. Kruglov., “My Experience of Studying the Holocaust,” https://blog.ehri-project.eu/2022/10/06/studying-the-holocaust/. ↩

- More about the activity of the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies: https://www.holocaust.kiev.ua/. ↩

- More about TKUMA’s activity: http://www.tkuma.dp.ua/ua/. ↩

- For example, one of the public discussions “Ukrainian nationalism and the Jews (1920s-1950s),” organized by the Center for Interethnic Relations Research in Eastern Europe, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qiVLNwDomDk. ↩

- Mnemonics’ yearly conference addresses Holocaust memory, national minorities and the memory of titular nations, the commemoration of victims of genocides and mass murder, etc., https://mnemonika.org.ua/events. ↩

- The organization’s website: https://aftersilence.co/. ↩

- See https://uamoderna.com/pdl-min/mizhnarodni-seminari-podolannya-minulogo. ↩

- In particular the Suspilne project “Holocaust. Zasvidchenyi zlochyn”: istoriï pro vyzhyvannia ta masove znyshchennia ievreïv. On the Holocaust in Rivne: “Rozstriliane misto,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7QcMYrFNXc; “Doroha smerti ‘Rivne-Sosonky’,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jZVIKIuWYlA; “Povstannia pryrechenykh,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Si_rD1QbNLg; the Holocaust in the Lviv region (Turka), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nv1MQRpj0oc; “Nevidomyi Holokost,” episode I, POWs, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXb8WQtFSko&t=3s; “Nevidomyi Holokost,” episode II, Cherson ghetto, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qyaBSFGMpEQ&t=1s; Do 80-richchia masovoho rozstrilu rivnens’kykh ievreïv u Sosonkakh, Chastyna II, Rivne Oblast Academic Library, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wC6uhQq9KbI; Za poklykom sertsia, Mariia Slobodiuk, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qx8928-25e8&list=PLJsM_752LpLLbnCBk3mJ-vaUyaOFSzVPp&index=5. ↩