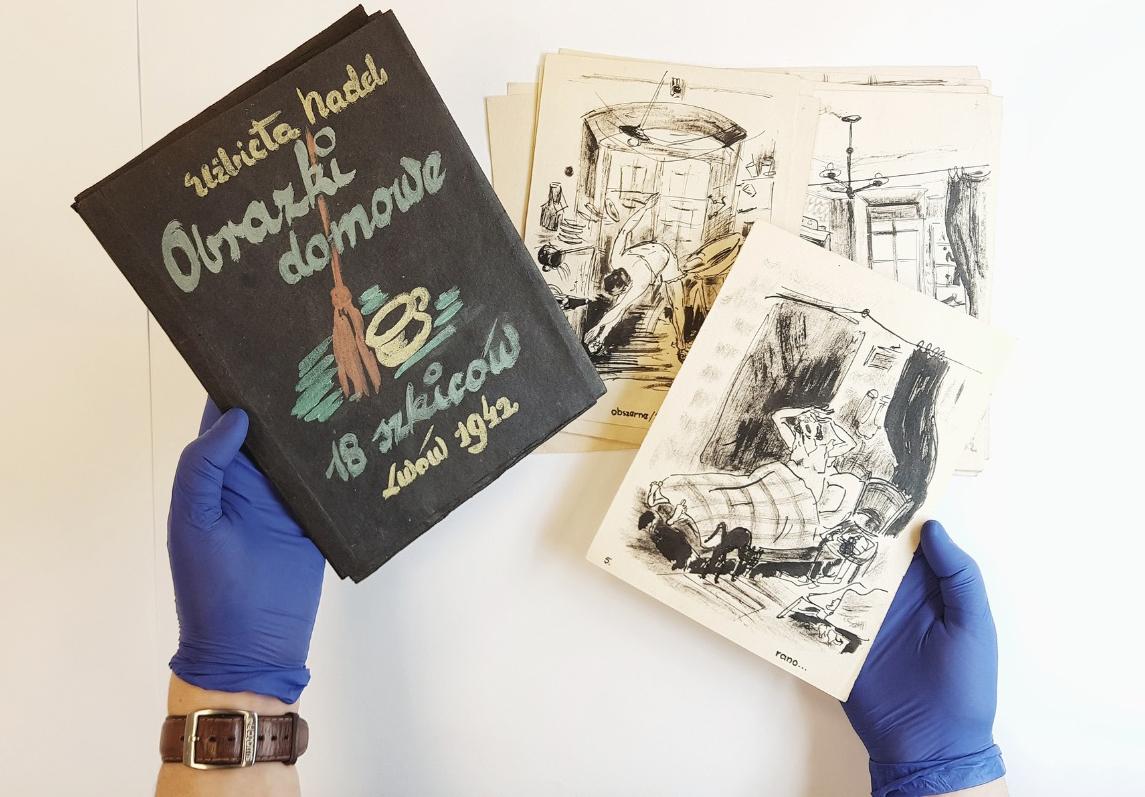

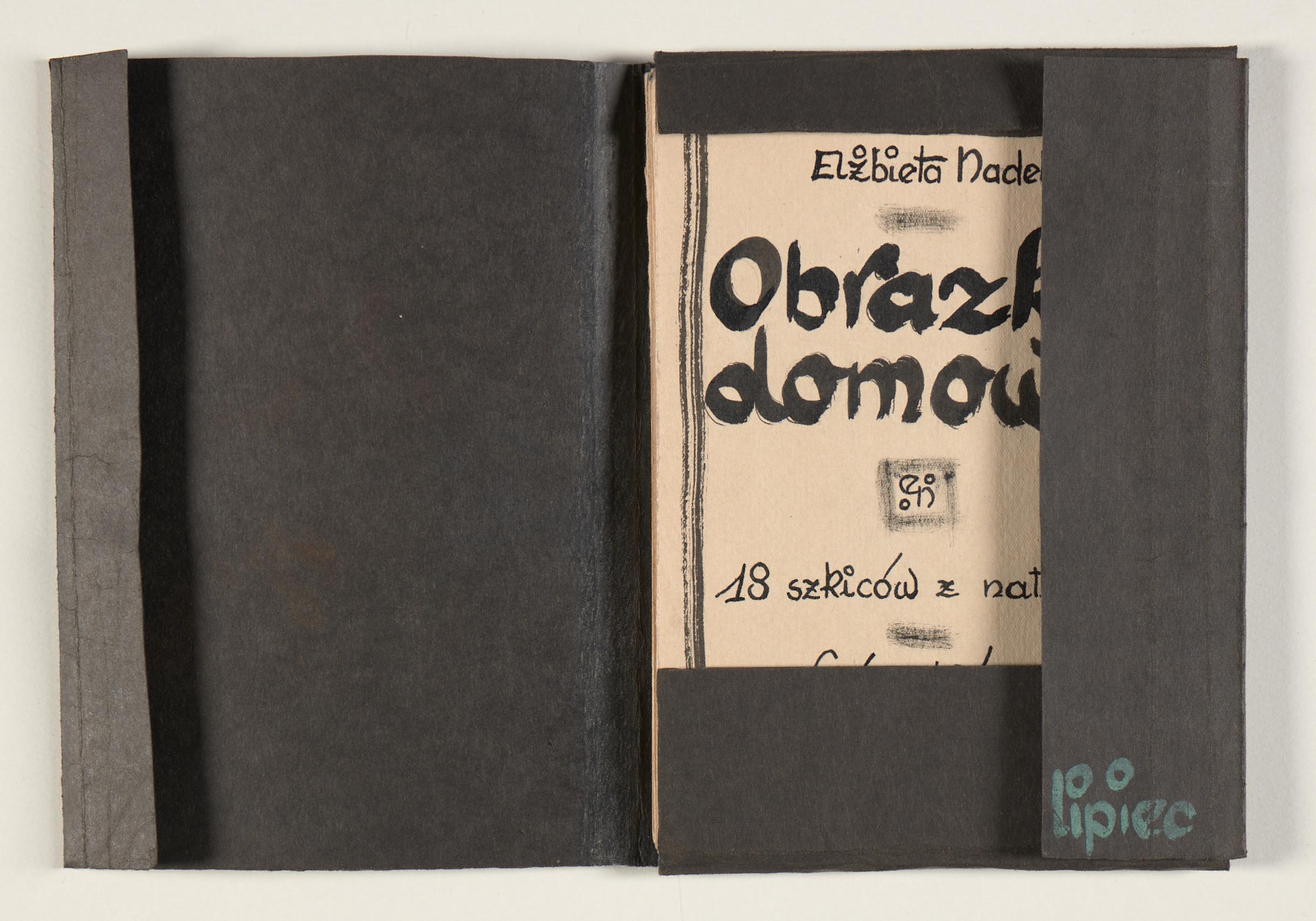

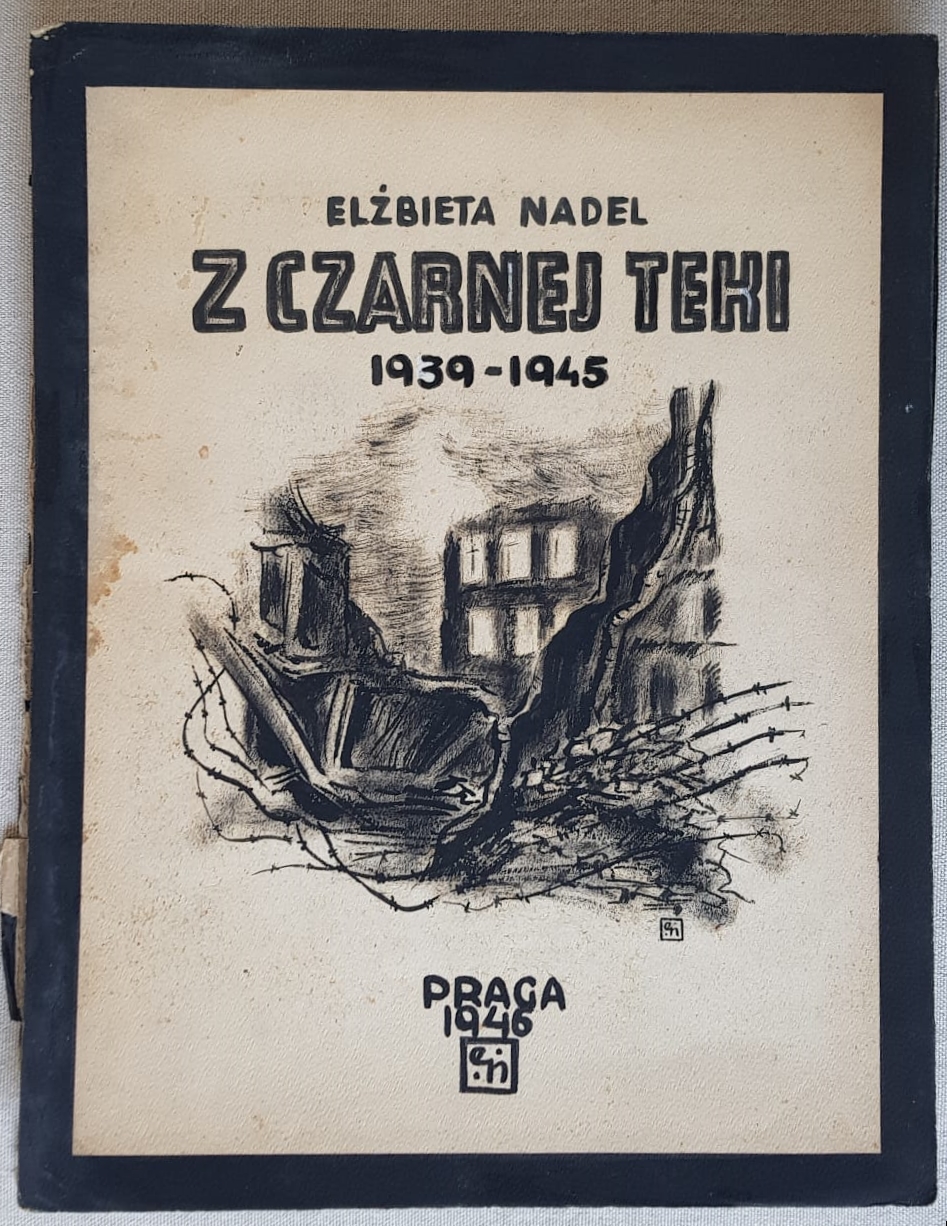

In late 2020, I stumbled across a curious listing in the USHMM’s online database: an entry labeled “Z czarnej teki 1939-1945 (The Black Album1, 1939-1945) / Elżbieta Nadel.”2 It was described simply as a set of 19 small photographic reproductions mounted on black cards measuring only 14 cm that was made in 1946 in Prague. There was surprisingly no information about the work’s provenance, content or its author, who is also listed as Landaʼu, Elisheva (1920-1994). But my curiosity was piqued, in no small measure because Elżbieta Nadel created another album in Lviv in the summer of 1942, Images from Home (21.5 × 16.4 cm), which has recently been the subject of critical and popular attention. It was discovered in 1999 in Kraków3 and then exhibited for the first time in 2012 at the Bełżec museum before it ultimately found a home in the POLIN museum as part of their permanent exhibit.4 Around the time I came across the record in the USHMM, the art historian and Chief Curator of Collections at POLIN, Renata Piątkowska had just devoted an entire article to the album.5 Although she hails Images from Home as a “not merely a great work of art − it is also an account, a report and a testimony on the Holocaust,”6 The Black Album has never been reproduced, exhibited or analyzed in the critical literature.7

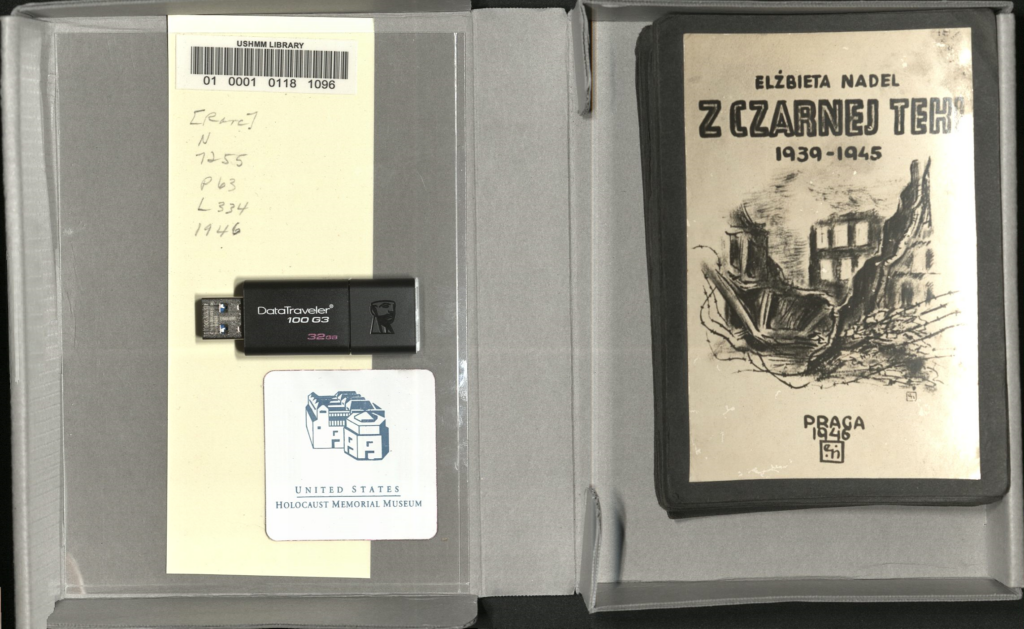

Such early postwar albums like Nadel’s are frustratingly difficult to find in the archives. I discovered The Black Album by pure serendipity. I had been searching in the USHMM database for postwar albums, but it was classified under the strangely anachronistic subject and keywords “Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945), in art,” despite the fact that it was not made between 1939-1945 but after the war. This subject heading offers important information about the work’s content (what it depicts), but it disregards its temporality: when, where, how and why the work was made after the war as a form of visual testimony. The subject specification “in art” suggested that this was not−as I had imagined−a traditional personal album comprised of photographs and mementos, despite Nadel’s use of the word “album” in the work’s title, but of artworks. The Black Album is nonetheless categorized under the format heading “book” and inventoried in the rare book collection rather than the art collection no doubt because it contains reproductions rather than original works of art. This archival classification has profound implications for the work’s visibility and bespeaks its value within the archive. Indeed, the USHMM archivist admitted to me that, “To be honest, neither our Archivists or Curators have looked at this in detail, as it is part of the rare book collection in the Library, rather than part of our archives and art collection.”8

The entry offered no information about the work’s provenance, technique, or composition−although a Google search clarified that it had been sold at a Kedem online auction, 02 – Rare Books, Bibliophilic Editions and Art, on May 24, 2016, and purchased by the USHMM for a mere $750.9 But what did The Black Album depict? How was it made and why? Were these “photographic reproductions” based on drawings or paintings or prints? Were they collated and mounted onto black cardstock or was the black funereal border painted? Were the panels bound in codex-form or were they separate sheets as in a portfolio? Were there other copies of this album? And where were the originals?

I spent months trying to consult the work from my home in Israel. Although the work has been digitized, thanks to the Tocker Foundation, the electronic version is only available by appointment internally, in the USHMM’s Rare Books collection which is housed off-site in the Shapell Family Collections and Conservation Center. Unable to travel to the States during one of the COVID-19 lockdowns, I emailed staff and colleagues in DC with repeated requests to view the digital file. When I ultimately received it, it didn’t appear to match the listing. The entry specified 17 panels, in addition to the cover and numbered index, but the file I received only contained 14 panels, three short. Moreover, the order in which they had been scanned didn’t correspond to the captions Nadel had provided in the index in any discernable way. I spent hours trying to pair the images with their titles, with mounting frustration. When I contacted the archivist with this discrepancy, a new file was sent that contained a photo of the box, including the “cards” in it. This allowed me to see its size as well as its composition as a portfolio. Although it now contained the correct number of 17 panels, they still did not correspond to the order Nadel specified.

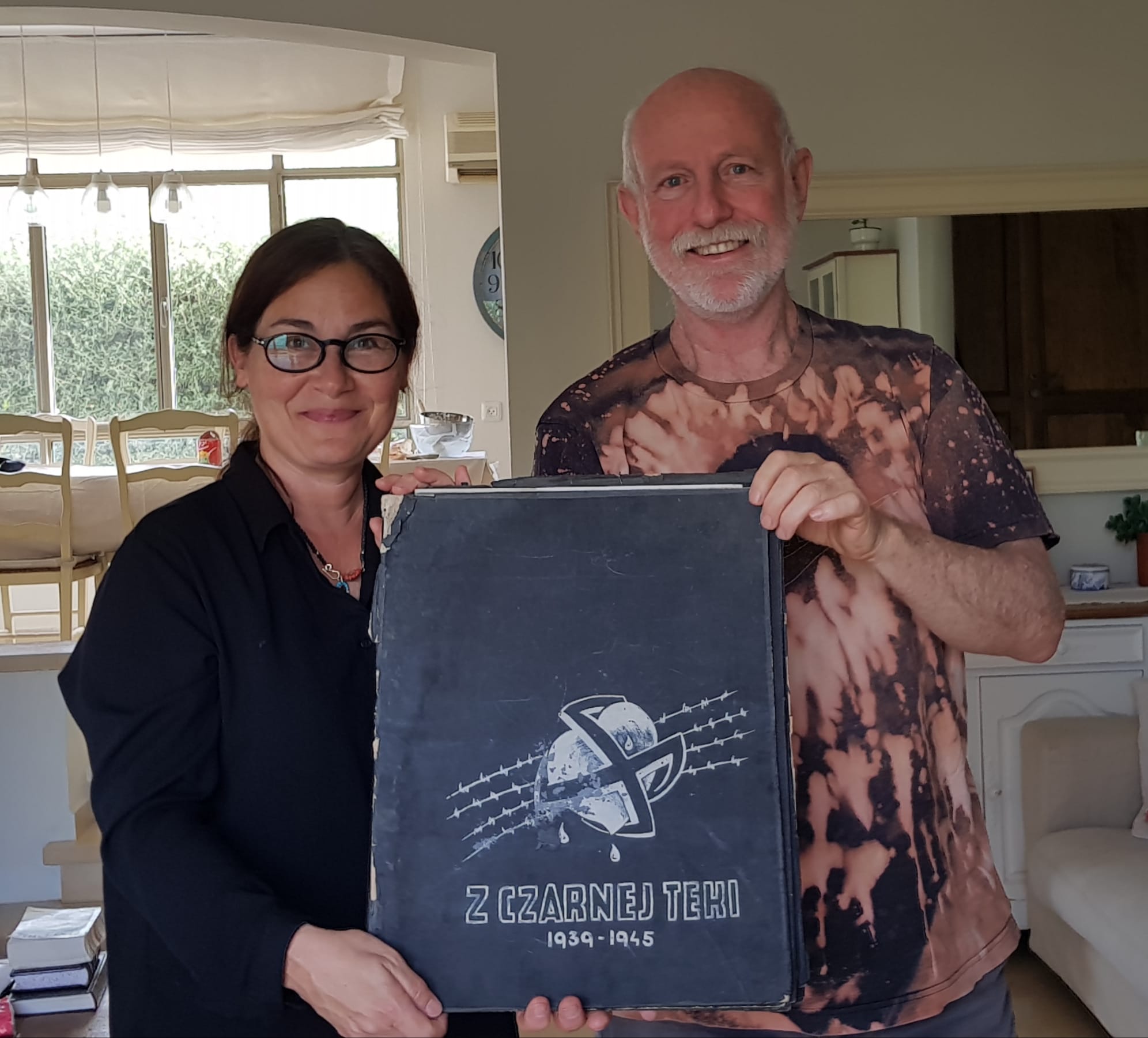

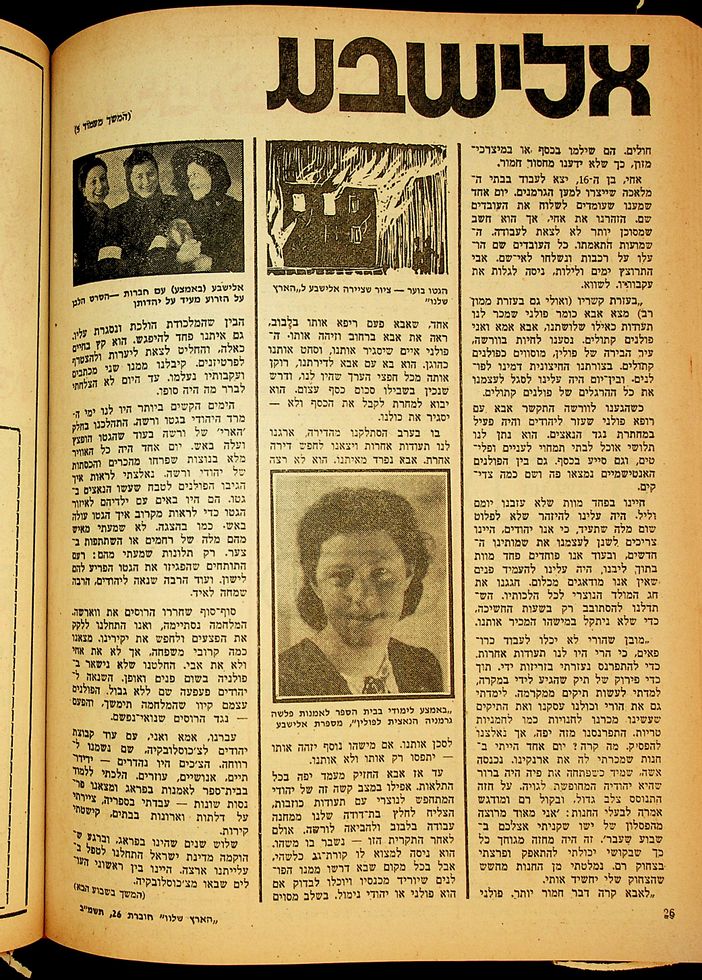

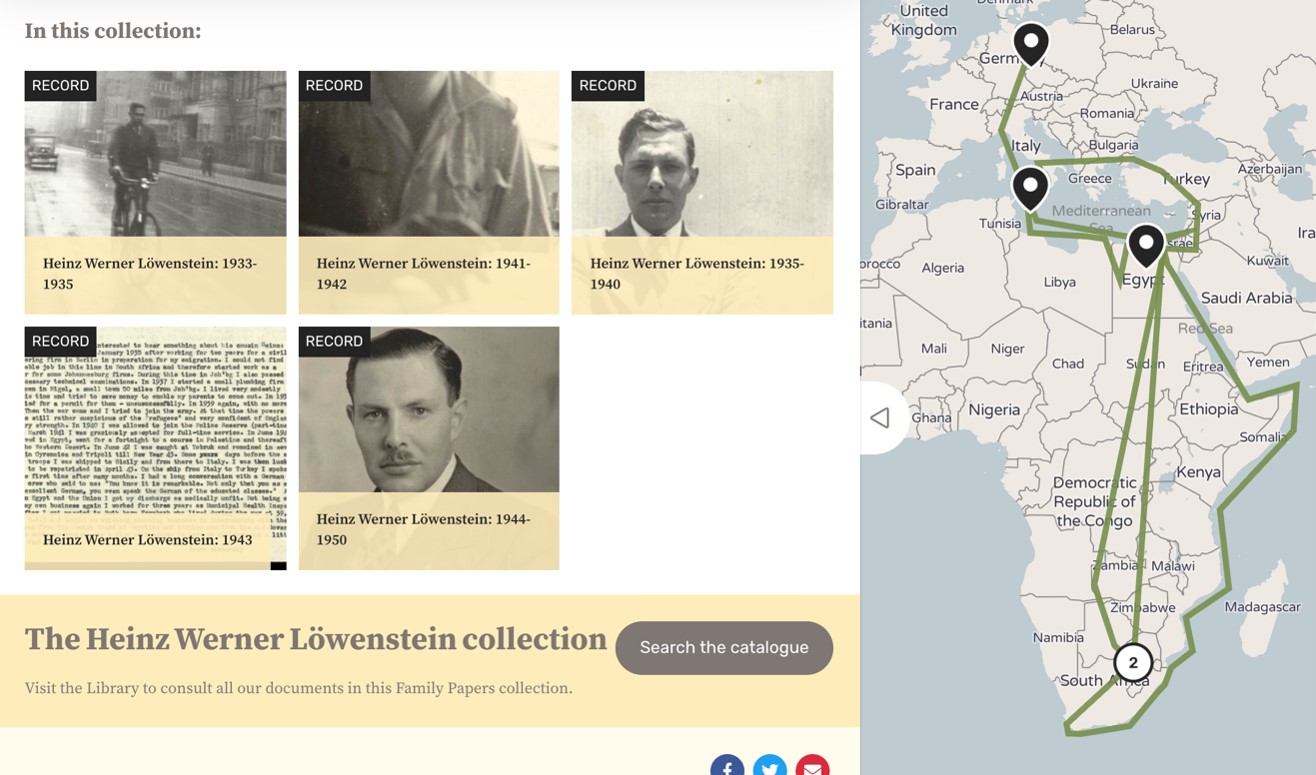

In the meantime, I tried to piece together Nadel’s postwar route to Israel and her activities once she immigrated. Nadel thought and worked in “picture stories”10 or “image-texts” throughout her life.11 After several years in Prague, where she worked as a graphic designer12, she made Aliyah to Israel in 1948, where she married Naftali Landau and had an illustrious career for thirty one years as the in-house cartoonist for the children’s weekly newspaper, Haaretz Shelanu under her married name, Elisheva Landau. In addition, she illustrated more than 100 children’s books and became one of the very first women cartoonists in the State of Israel, illustrating comic books by Pinchas Sade and Jacob Ashman, and in particular his Israeli superhero Gidi Gezer, a Palmach fighter.13 In Eli Eshed’s blog on Israeli cartoons, I came across important biographical information on Nadel (now Landau) as well as a reference to her two sons.14 After countless emails and phone calls across the globe, I finally got in touch with her youngest son who lives in Chile, and who put me in touch with his brother who lives, by pure kismet, not far from me. Like the well-known fable, the treasure was, in fact, buried in my backyard all along. After months of doggedly trying to track this little album down, to see it and hold it in person, my efforts were rewarded. On one otherwise unremarkable weekday, we arranged to meet and he brought with him his mother’s Black Album. When he entered, I expected to see a very small booklet of 14 cm. in height−like the one listed at the USHMM. What he took out from his plastic folder was–is−enormous: a massive portfolio enveloped in a beautiful black folder, measuring 45 cm x 35 cm, and comprised of original ink drawings and paintings.

This article offers a close reading of Elżbieta Nadel’s recently discovered The Black Album which is unlike any other work she made before or after.15 Because we have two albums by the same artist−Images from Home made during the Holocaust and The Black Album made in its immediate aftermath−we have a baseline for comparison. In tone, style, content, voice and point of view, The Black Album bends to the pressures of its time and its function after the war.

Remembering to Draw: Images from Home

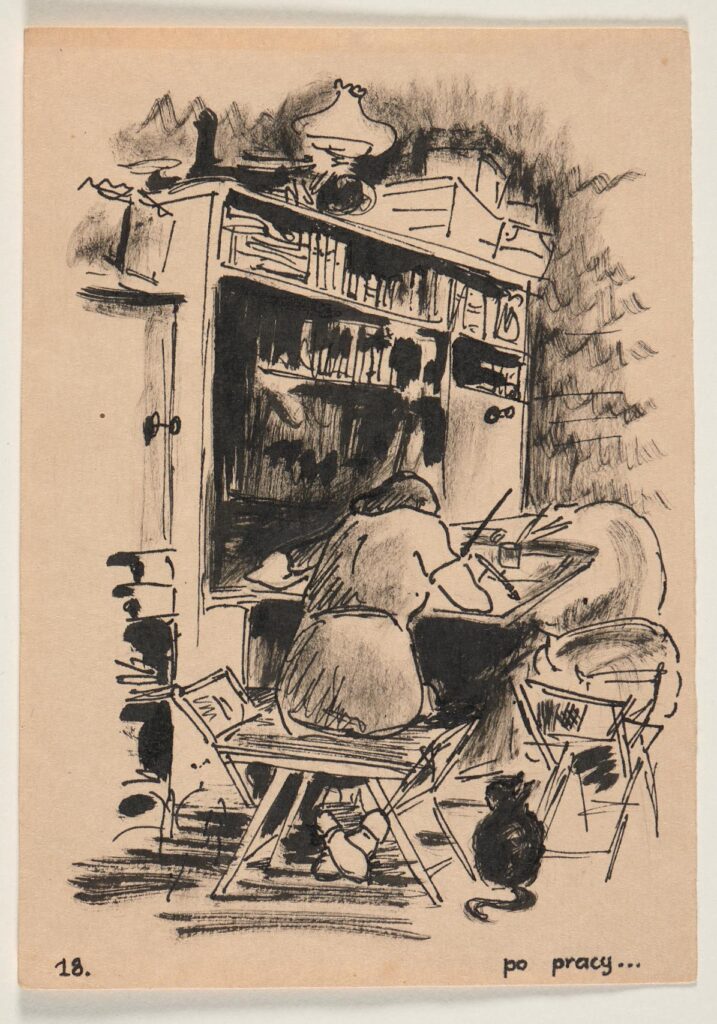

Images from Home is not a life story but a day in the life. Like a pictorial diary or medieval Book of Hours, Nadel pulls us into the dailyness of her immediate present, detailing the rhythm of her diurnal routine in her home in Lviv in July 1942.16 Mapping space and marking time, her chronicle progresses from “morning” to “at dusk,” “in the evening” to “after work” as she wakes up, cleans, exercises, bathes, etc. Each panel has a hand-drawn, scriptive caption beneath in Polish. We follow the artist-author and her nuclear family (mother, father and brother) spatially and temporally from hour to hour, from action to action and scene to scene over the course of a single 24-hour day. Throughout, the narrative follows a discernable thread that connects the panel-to-panel transitions and constructs a continuous reality, oriented in a unified space (of contiguous rooms) within a clearly delineated time that drives the narrative forward. In fact, Nadel has constructed what Frances Yates called a memory palace17 − and one sees this most markedly in the overhead architectural floorplan she includes, drawn to scale 1:66, which orients the viewer as they transition from page to page and through the different rooms in her home. Like this spatial diagram, the album itself serves a mnemonic function for the future; as a visual memento, it records a difficult time and place by linking places (loci) with images (imagines) to enhance the recall of information for future recollection.

Entrapped in a perpetual present of “numbered days,” to borrow the title of Alexandra Garbarini’s book on wartime dairies, Nadel labors to keep time and piece it together into a coherent chronology through a sequential narrative.18 By tracking time in this manner, Images from Home literalizes the victims’ attempt to “hold it together” and control time, if only in the space of artistic creation, when they were denied this very agency under conditions of Nazi oppression. Cut off from her past and suspended in a precarious present with little knowledge of the future, Images from Home assumes a holding pattern; it figures what Lauren Berlant calls an “impasse,” the “temporal genre of the stretched-out present.”19 She is caught in an endless circular temporal loop, with the suggestion that one day is like the next.

On the front cover, she has drawn two motifs of her daily tasks, a broom and a chamber pot−signifying a desire to sweep the shit of daily life away−rendered in light blue, dusty ochre and earthy rust gouache. Instead of simulating a mechanical typography for the text, she has used her own informal, cursive handwriting to foreground her autographic presence. Her subtitle “18 Sketches from Nature” insists on these sketches as being “from nature,” thus reinforcing her role as a documentary eyewitness, recording her life naturalistically. It also emphasizes the number of panels, 18: a number which stands for the Hebrew word “chai” (חי) meaning life, as it is made up of the letters chet (ח), the 8th letter in the alphabet, and yud (י), the 10th. Spotlighting this number asserts the importance of carrying on with life, even under extremely difficult conditions. But the captions within are laced with ironic undertones: she facetiously describes her trip to the bathroom down the building’s narrow stairwell as her “Daily stroll…” The crowded, messy kitchen with stacked pots and clothes draped on makeshift lines is sarcastically entitled “Nice…” Such commentaries leave off with an ellipsis that indicates irony. These dot, dot, dots lay bare the gulf between her past and current reality and interject the artist’s feelings about her current circumstances.

Despite her sweet, wistful images of home and attempt to maintain a semblance of normalcy, we see the temporal constriction and spatial restrictions of ghetto life. Renata Piątkowska suggests that Nadel’s preoccupation with thresholds, doors and windows signals “a line of defense” protecting her “oasis of refuge,” but they also radically redefine “home” as a site of what Imke Hansen, Katrin Steffen, and Joachim Tauber call “restricted life.”20 The album begins with a view of the exterior, outer door to their apartment (1); it figures her exercising in front of a closed door (3), washing in a basin framed by a doorway (6), sleeping on beds that spill through the doorways between rooms (7), looking out of a window (10), through a corridor (11), onto the doors of the privy (12), a dinner table between a door and a window (13), cleaning with the window open (14), chopping wood in a doorway (16), and looking out an open window (17). These recurring images of doorways and windows expose her lack of purview beyond the enclosed, hermetically sealed space of her home. They point to the tension between the private and the public, inside and outside−a tension which will carry through to The Black Album as well.

Images from Home ends with the generation of the booklet, with herself “At Dusk,” after the chores of the day are over, sitting at her drawing table−a perfect circle closed. In this way, it resembles the final image of that most famous graphic narrative created by a young woman during the Holocaust: Charlotte Salomon’s Leben? oder Theatre? (Life? or Theater?) created between 1941 – 1942, when she was living in exile as a refugee in the South of France. Salomon’s genre-bending work, comprised of 759 gouache paintings and accompanied by textual narration and musical cues arranged into acts and scenes, concludes with the artist kneeling by the shores of the Mediterranean Sea as she begins the work at hand. So too, Nadel underscores herself as both the subject of this narrative, its protagonist, but also its narrator: the one who tells the story, shapes it and draws it and draws herself drawing it. Although she ends with the quiet power of art making and storytelling, on the album’s back cover, her authorial monogram −e./n.− is inscribed inside of a large, rust-colored Jewish star as a potent reminder that she was trapped by her identity as a Jewish woman under Nazi rule.

Shortly after she completed Images from Home, Nadel was forced to leave her home during the “Große Aktion” of August 1942, when her sixteen-year-old, younger brother Jerzy was murdered.21 She left Lviv with the assistance of a Righteous Among the Nations named Kazimierz Moździerz (1918-1997), who had been her friend at the Institute of Fine Arts in Lviv.22 In testimony she gave to Yad Vashem on his behalf in 1987, Nadel wrote that Moździerz was “the only friend who did not break contact with us after the Germans entered Lviv, visited us and was interested in our fate […] and escorted me and my mother to Warsaw and also helped us find an apartment.”23 She lived there, outside of the Warsaw ghetto, with her parents under false “Aryan” papers. After her father died, she worked with her mother as a nurse in army hospitals caring for wounded soldiers. After the end of the war, after, she writes, “searching for family members [in Poland] to no avail,” she moved to Prague with her mother − where she made another album, The Black Album.24

Drawing to Remember25

The Black Album is the sequel and near opposite of Images from Home. If Images from Home presented “18 Sketches from Nature,” The Black Album was fashioned “from memory,” over a year after the end of the war, in a new city and country. In it, she is no longer “writing in the days but rather of the days.”26 And rather than covering a single 24-hour day, The Black Album covers a long stretch of time: a period of six years, 1939-45. Moreover, whereas Images from Home, despite its known backdrop, is homey and affirmative with a physically intact home, secure family ties and narrative cohesion−suggesting resilience and creative resistance in extremis−The Black Album is dark in palette and in content. It figures a world in reverse, an eclipse.27

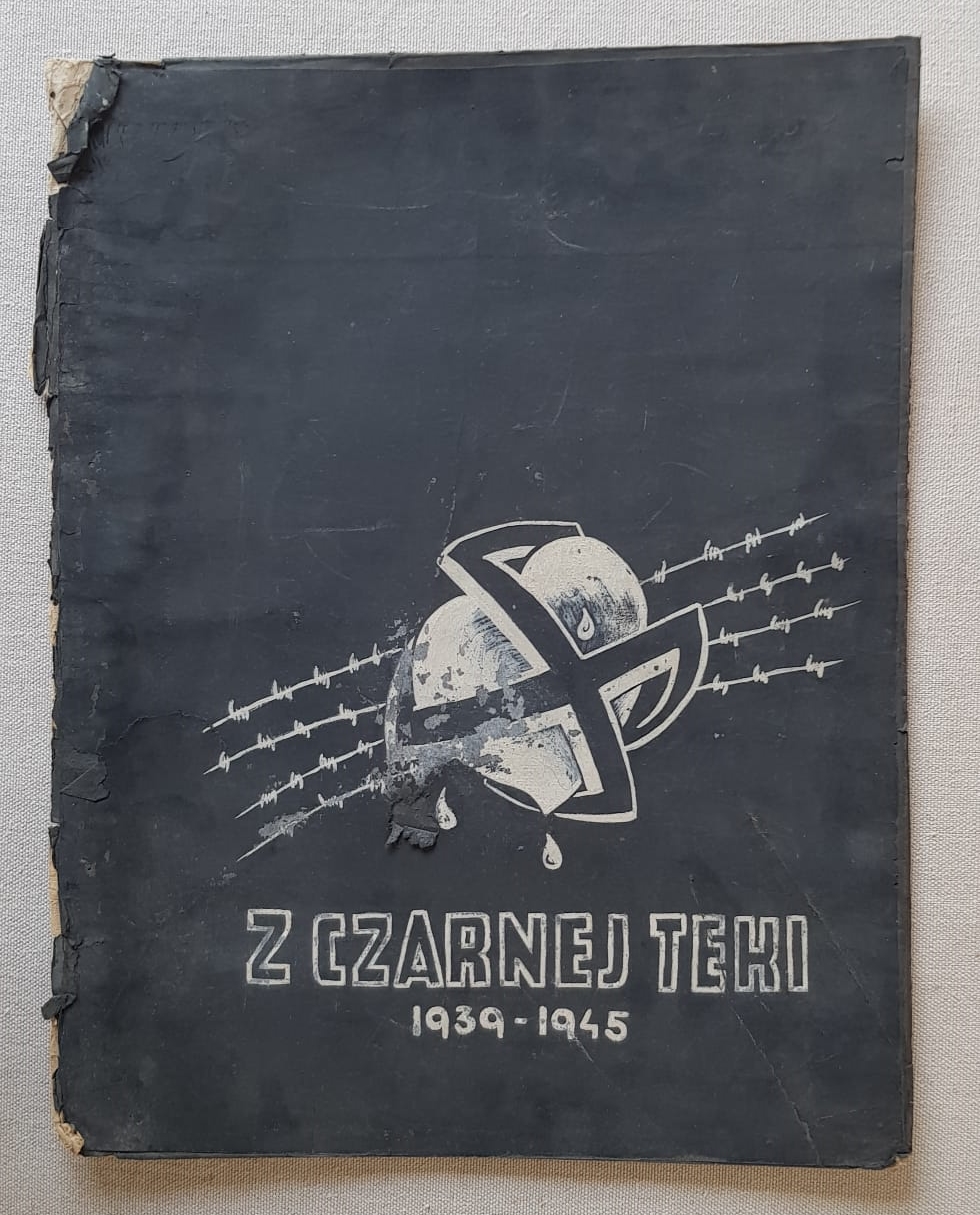

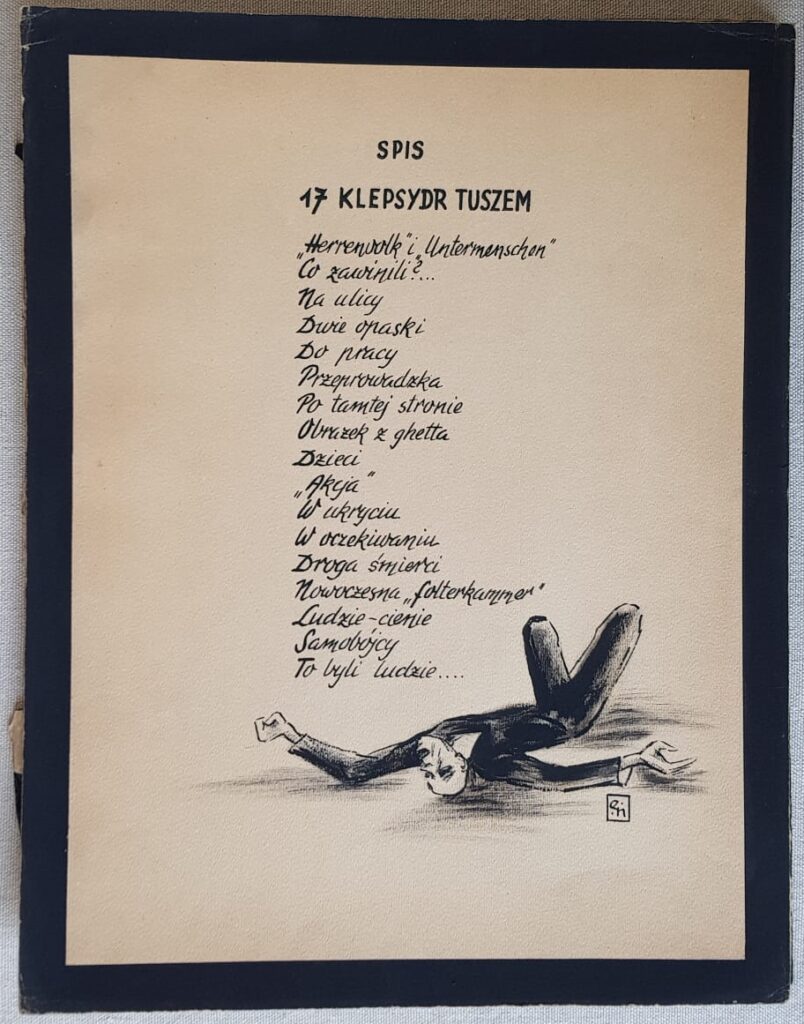

For the original album’s folder (which is missing in the USHMM version), she trades the informal, handwritten cursive typography and colorful gouaches that animate the cover of Images from Home for bold, drop-shadow block letters in all caps and a single motif: a heart, caught in a vise and crushed so tightly by a black swastika that it emits teardrops, against a barbed wire. On the cover, the safe space of the home so lovingly depicted in Images from Home is destroyed and uninhabitable. We look through wreckage and rubble in the foreground to a demolished and abandoned home in the distance. Instead of the symbolically significant number of 18 panels in Images from Home, the Black Album offers 17, one short of “chai” (life). The first page offers a table of contents or index labeled “necrologies” that are mounted over a dead, supine body, splayed out in rigor mortis. But these are not necrologies at all–at least not as they are traditionally understood: obituary notices or lists of the names of deceased individuals. In fact, Nadel neither lists nor depicts specific individuals, despite her considerable personal losses and most specifically the deaths of her brother and father.

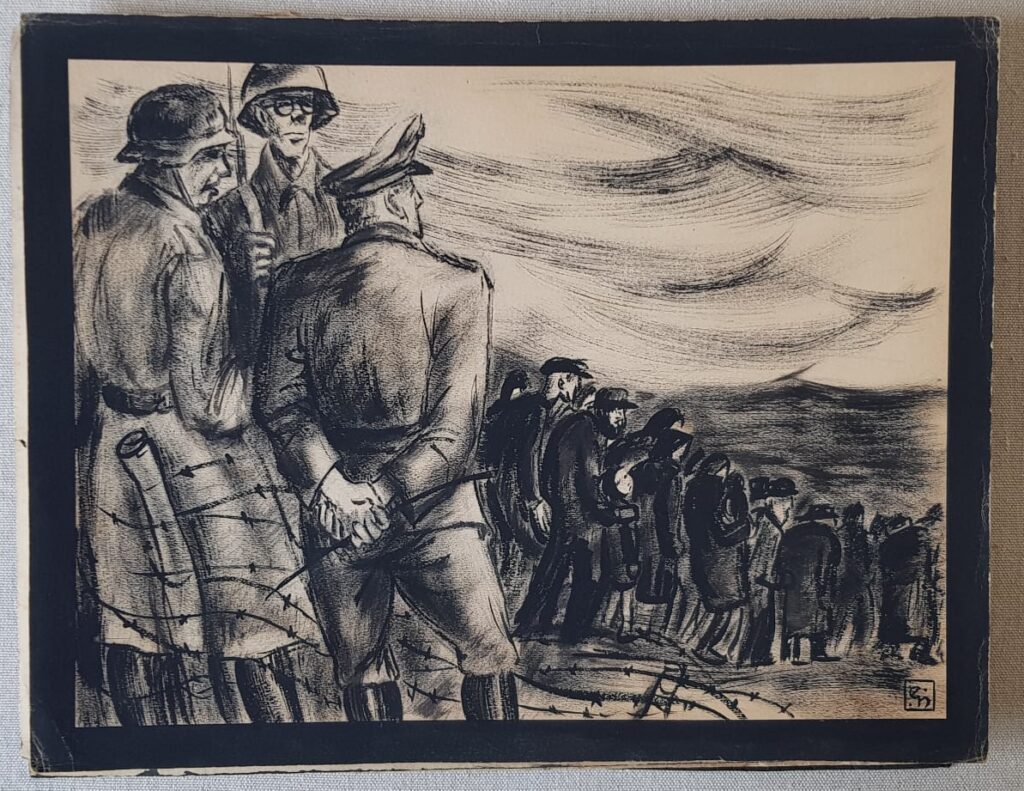

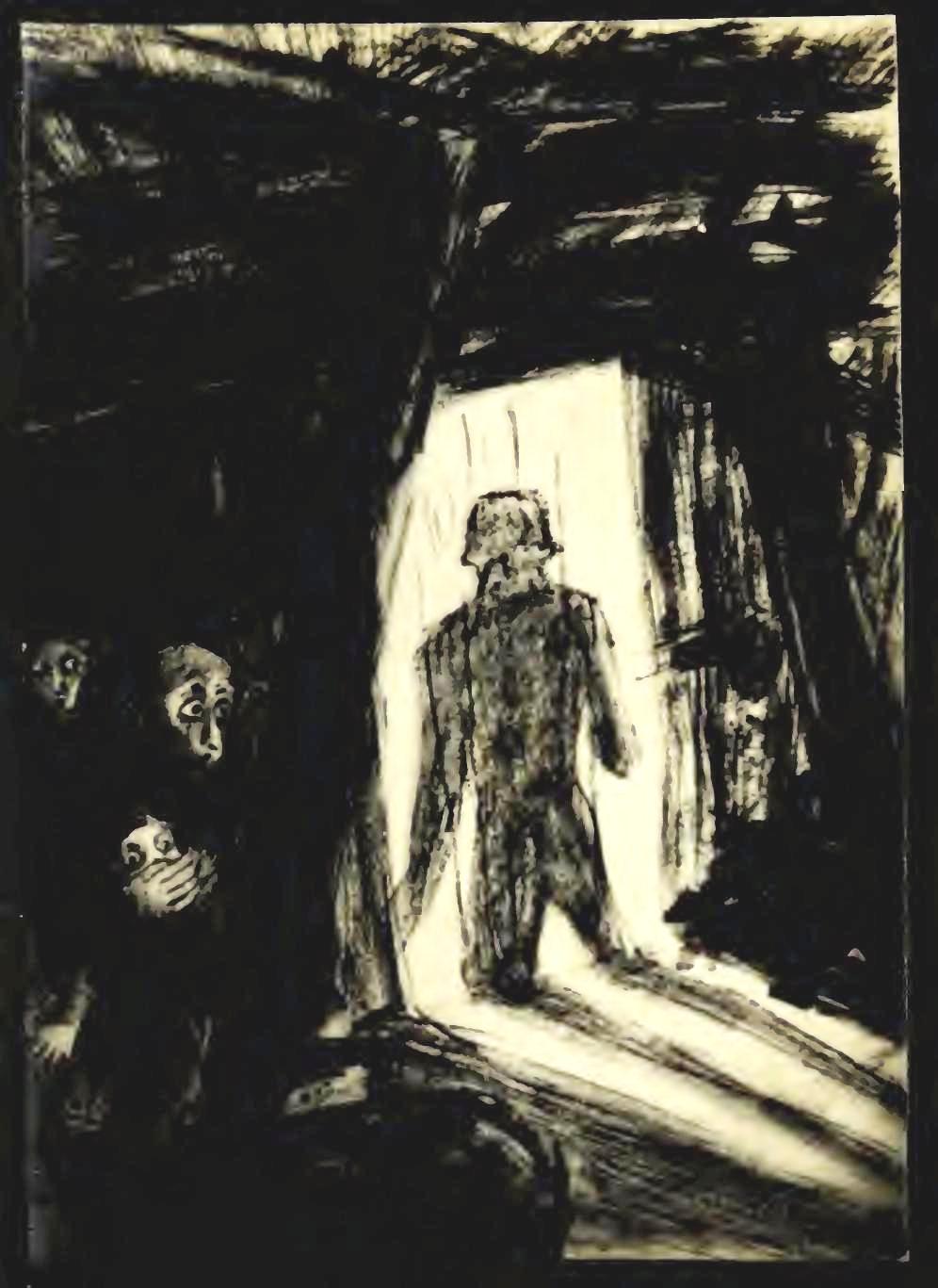

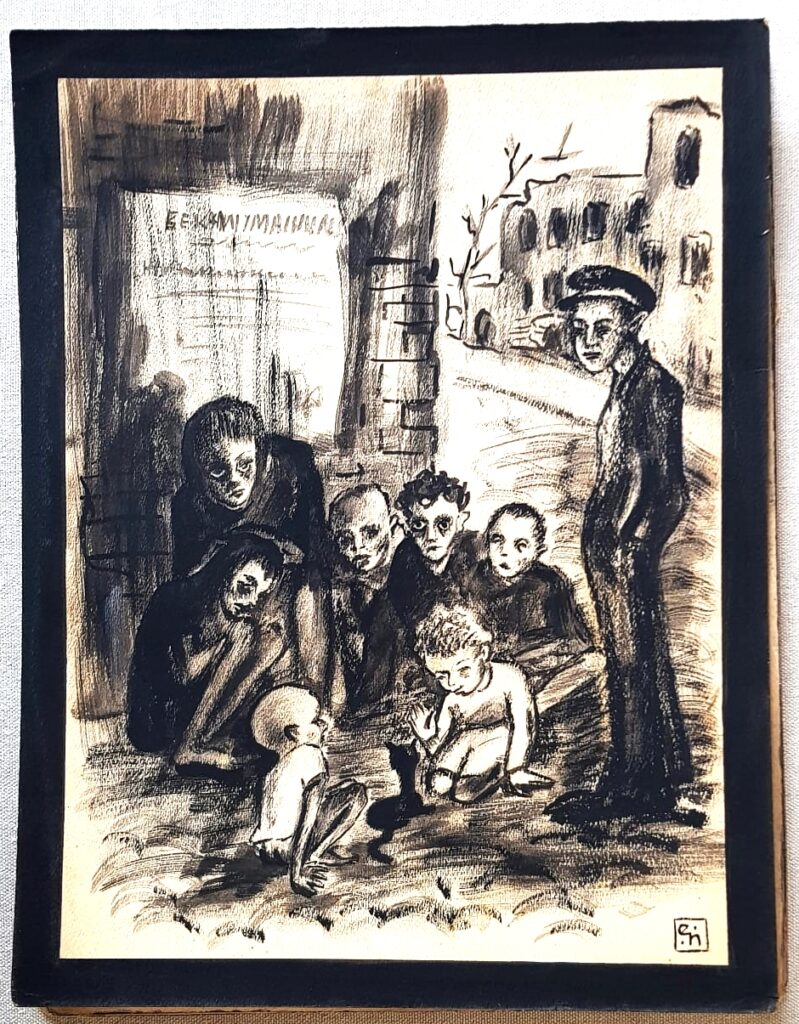

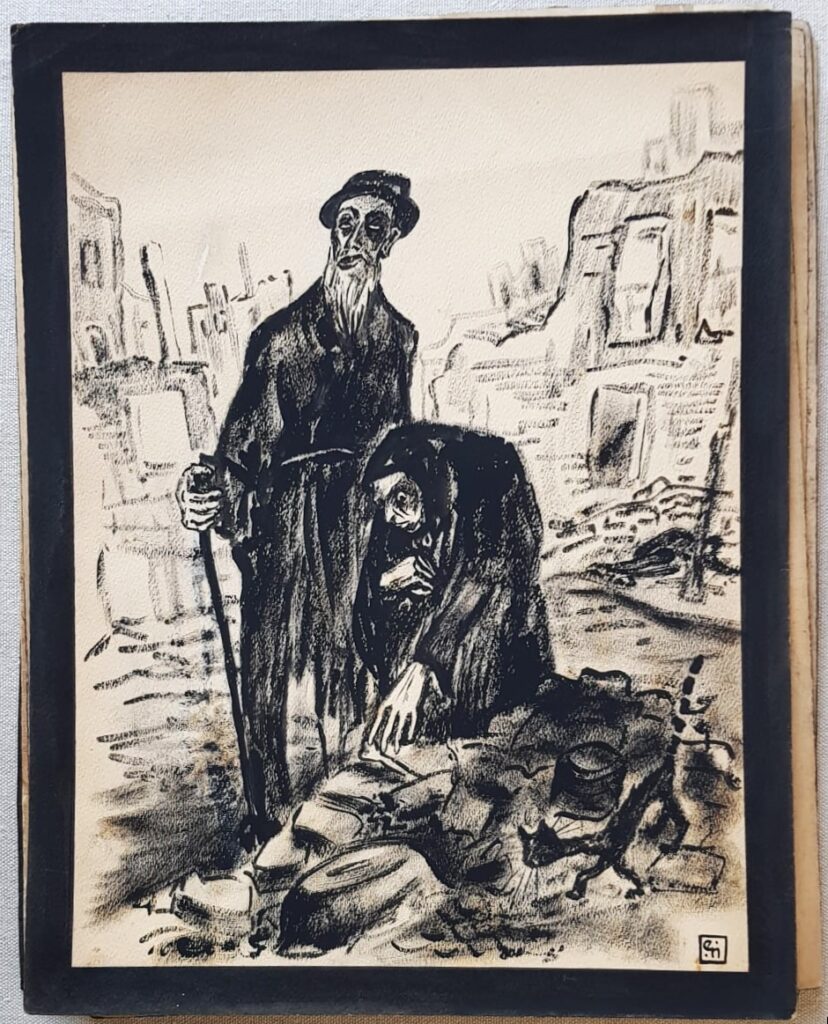

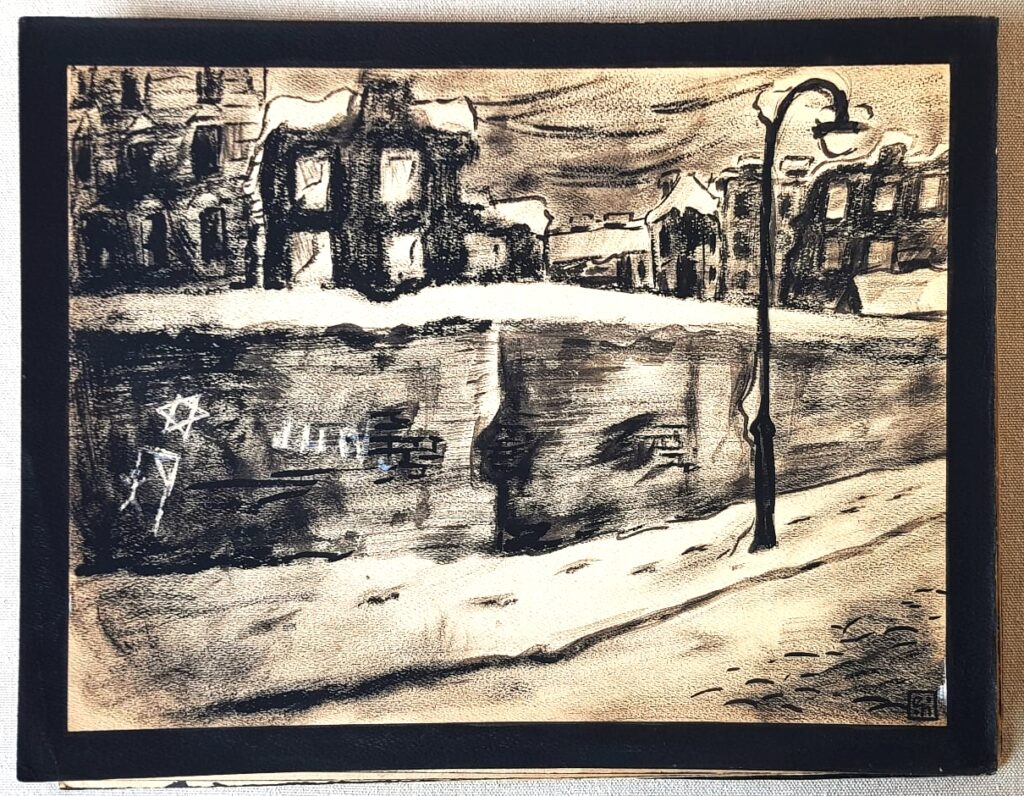

The album opens with the panel Herrenvolk and Untermenschen featuring the perpetrators, disproportionately large and menacing in the foreground, overseeing a deportation, with their Jewish victims as faceless, huddled masses in the distance. We then move on to: What Was Their Fault..?, In the Street, Two Armbands, To Work, Moving, On the Other Side, A Picture from the Ghetto, Children, “Aktion,” In Hiding, Waiting, The Path of Death, Modern Torture Chamber, People-Shadows, Suiciders. The Black Album grinds to a halt not with the joy of liberation but with a formless pile of corpses in These Were the People.28

Whereas the captions in Images from Home are themselves “at home” on the page, numbered and given to the reader with the image to facilitate reading, in the Black Album, words and images are decoupled. Because the titles are given at the front of the album on the index page, one needs to constantly flip back and through the album to identify what is shown to us. This is partly because there is no space left for textual explication: the image swells and encompasses the entire page, up to its painted funereal black border which bleeds into the empty gutters which traditionally give us room to breathe, a space of distance and detachment. And the panels, which were uniformly vertically oriented in Images from Home are now disorienting; they shuttle between portrait and landscape orientation (8 are vertical and 6 horizontal), alternating with little rhyme or reason and forcing the reader to constantly rotate the panels and reposition them.

In addition, the crisp, cartoony hard outlines of her pen are swapped for brush and ink, at times applied dry across the page or in heavy washes that seep into the page and create indistinct, blurry contours, as muddled and muddy as the masses and landscapes they depict. Private, protected spaces give way to open public spaces, where the individual is left exposed to the elements and the whims of the perpetrators (8, 10, 11, 12). Even interior scenes are under threat of invasion with titles like In Hiding and Waiting. So too, the close interpersonal bonds of the family unit break down: the young and the elderly are unprotected, left to fend for themselves unsupervised on the streets of the ghetto or to forage for refuse in its ruins. Nadel’s cat, her faithful companion and household pet in Lviv (and perhaps even an autobiographical avatar), returns in the Black Album as a scrawny, homeless alley cat, scavenging for food in the open.

Above all, it is the narrative structure of The Black Album that unsettles. Although adhering to a loosely linear chronology, from deportation to extermination, the panels frustrate narrative closure (where we observe the parts but perceive the whole by linking separate moments into a single idea and “mentally complete what is incomplete”).29 It is difficult to re-member these atemporal fragments and make connections between them to construct a continuous, unified reality. The panel-to-panel transitions verge on the most difficult kind: that of the non-sequitur (no logical connection between panel subjects) refusing narrative expectations. Time is fractured but so is space. The album jostles between disparities of scale and different viewpoints, and all sense of grounding spatialization is lost. We are jerked from close-ups to wide-angle panoramas, from figure to landscape, from the individual to the mass−and even from the graphic to the painterly, from the sentimental to the prurient, from pathos to shock, from figuration to abstraction−in what can best be described as a kind of “traumatic realism” to use Michael Rothberg’s term: a form of storytelling that is resistant to integration and narrativization.30

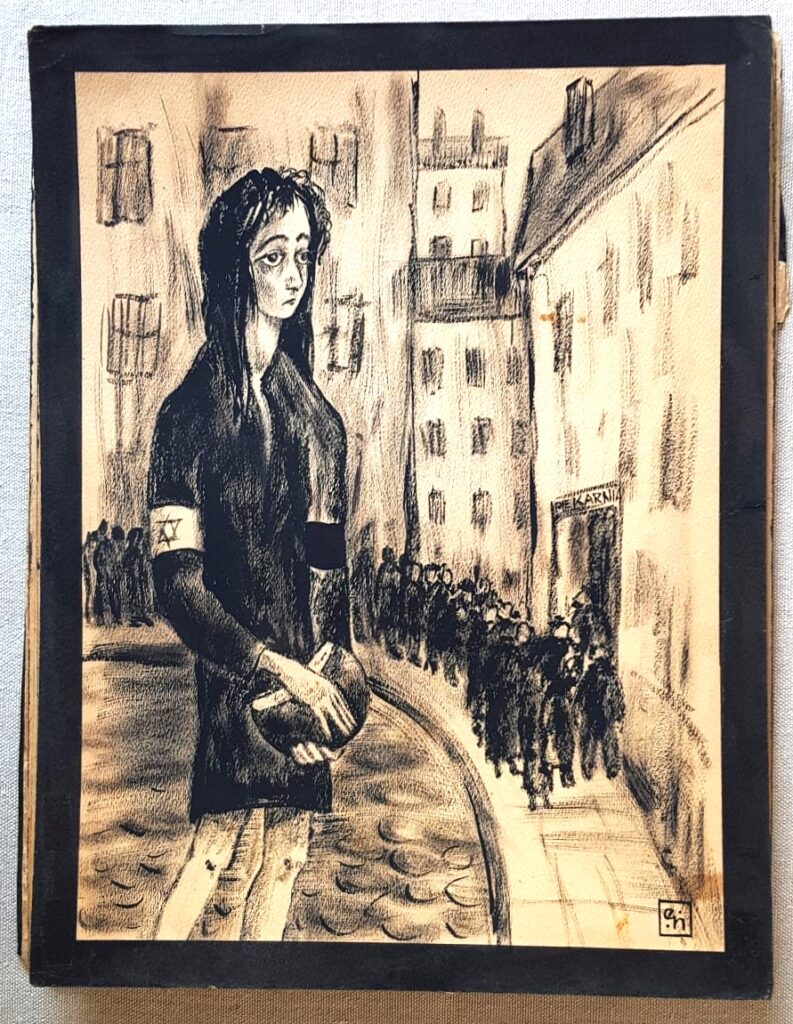

In addition to the radical shift in tone, style, content and perspective, the position of enunciation or authorial “voice” changes radically. Images from Home is emphatically autobiographical−detailing her personal space from her point of view. In The Black Album, the author Elżbieta, is only present in the monogram she draws in the bottom right corner of each page (her conjoined initials e./n.). Only one panel depicts a young girl (Two Armbands, no. 4) who stands dejectedly in the street holding a loaf of bread as a deportation takes place behind her. The interiority of the home is shattered, as is the interiority of the self. Nadel is present as author but largely absent as its subject.

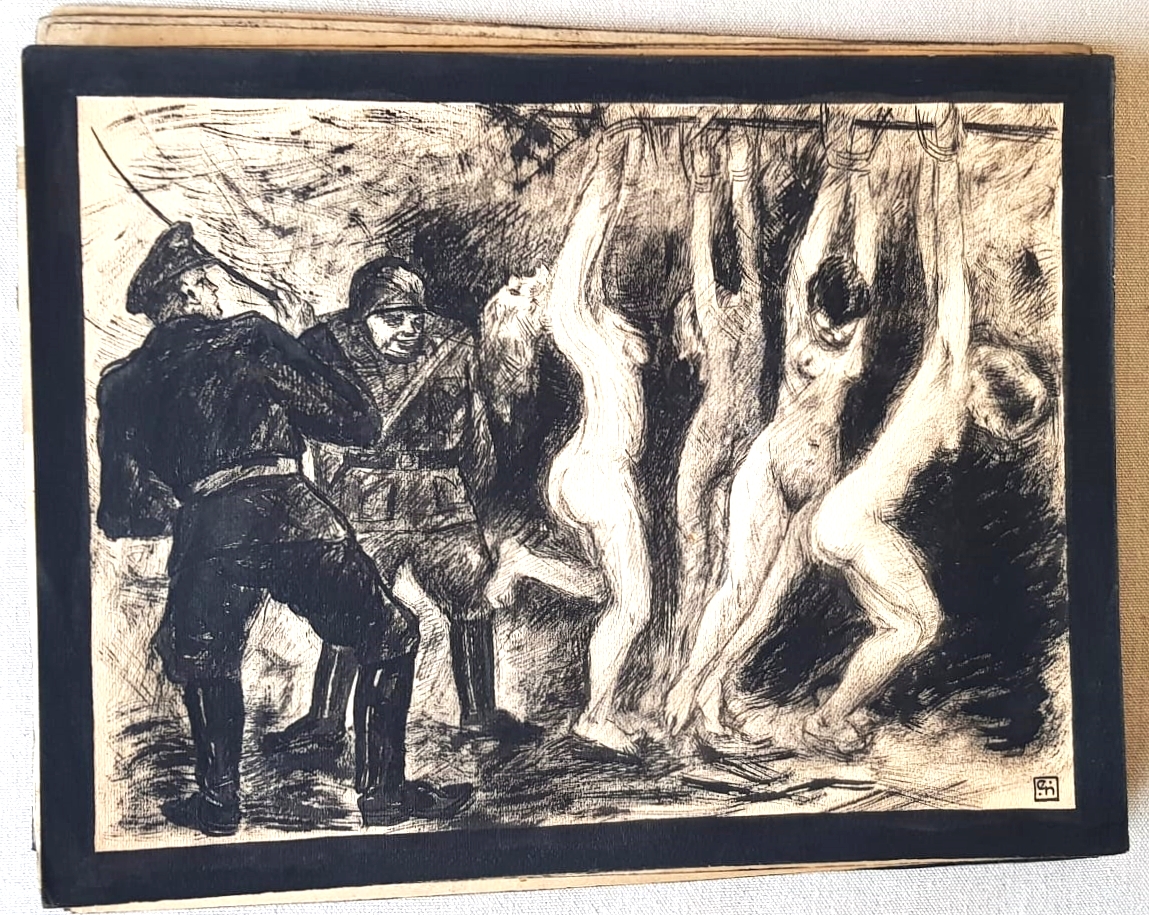

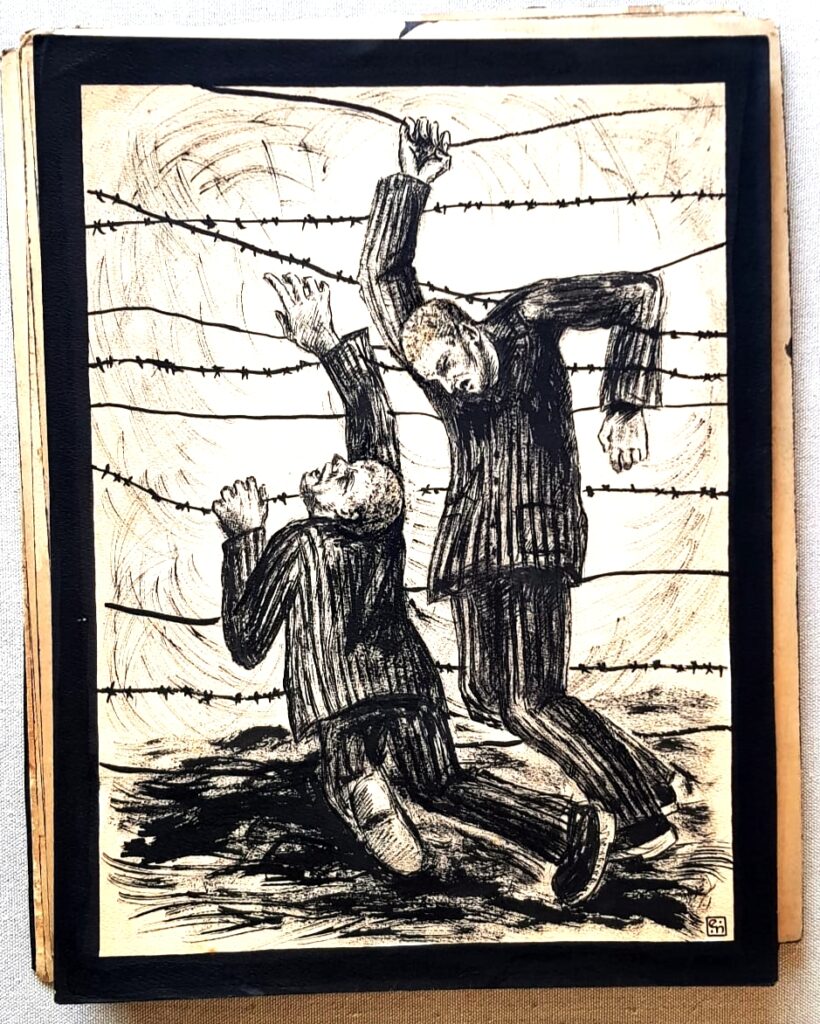

The Black Album defies easy categorization. It is not an autobiography, pictorial diary or memoir; nor is it, strictly speaking, a visual testimony given after the fact. Between the time she completed Images from Home and made the Black Album, a lot happened to Nadel, almost none of which is directly included in it. Nadel suffered greatly during the Holocaust, but she was not deported or interned in a concentration or extermination camp, despite her depiction of those scenes. She had eye witnessed some of the scenes depicted; others, however, she could not have seen directly. Had she personally been subjected to the physical torture of young women represented in Modern Torture Chamber? Or was she representing things heard or read? It is surely significant that, as a woman, she included this excruciating sadistic scene of sexual violence perpetrated against four naked women, bound and hanging by their hands from the rafters, shrieking in pain or slumped over, as two thuggish, leering Nazi soldiers in uniform whip them.31 So too, she most certainly never witnessed the scene depicted in Suiciders, of two dead inmates against barbed wire, as she never stepped foot in a concentration camp. By this point in 1946, she would have seen the widely reproduced photographs of dead inmates against barbed wire that were also figured in Fritz Lederer’s massive album published a year later near Prague, In the Eruw of Theresienstadt. These postwar graphic albums cause trouble for scholars as visual testimony; they are deemed “inauthentic” as a form of visual witnessing because they are not records of lived experience but instead rely on recirculated iconic images.

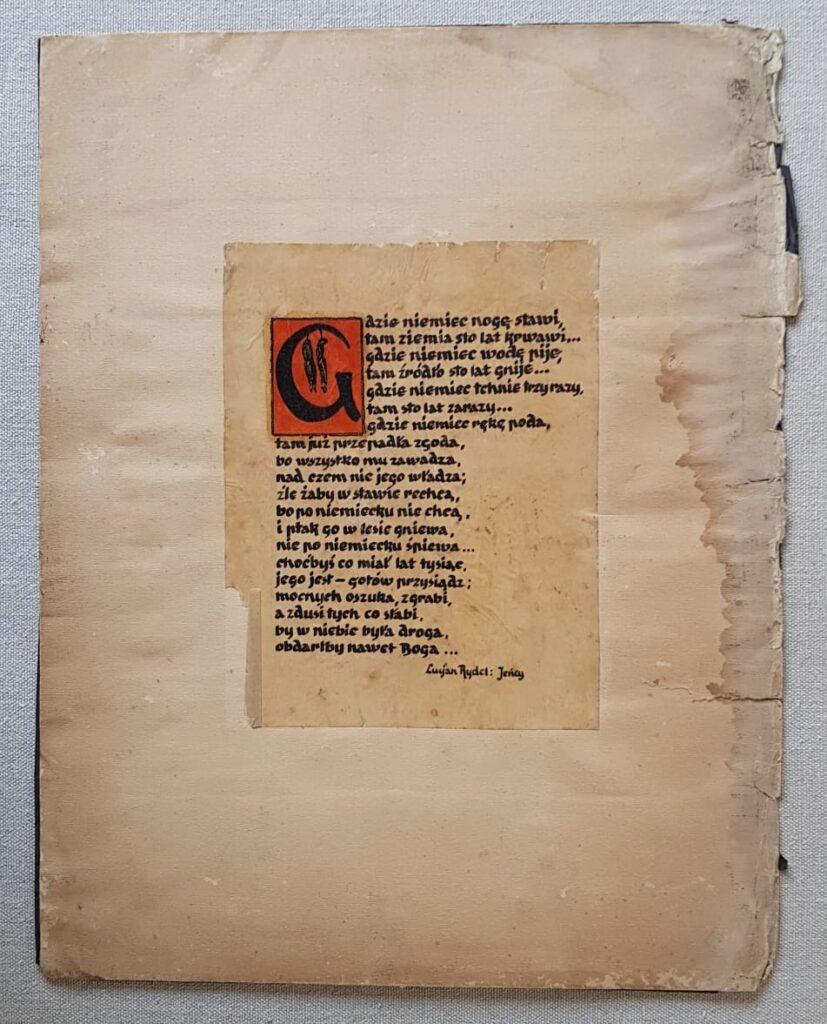

The Black Album represents Nadel’s experience of marginality and victimization, as a woman, as a Jew and as a Pole. Throughout, her Jewish identity figures obliquely and directly in the Jewish star worn by figures in Two Armbands (4), To Work (5), and Moving (6), and as graffiti on the walls of the ghetto On the Other Side (7). But collated to the back page of the cover, Nadel includes an epigraph: a page of excerpts of Polish playwright, Lucjan Rydel’s drama Jeńcy [Captives], written a half century earlier, in 1902.32 Jeńcy is introduced at the outset to signal her Polish identity and gesture to a much longer history of anti-German sentiment within Poland. Inside the enlarged, illuminated first initial “G” (for Gdzie meaning “Where”), two figures hang on gallows against a blood-red background. This decorated capital letter is historiated (it shows a scene) and “inhabited” by signs of Nazi persecution. Rydel’s text reads:

Where the German sets down his foot, the earth bleeds for 100 years.

Where the German carries water and drinks, wells are foul for 100 years.

Where the German breathes three times, the plague rages for 100 years…

Where the German shakes hands, peace breaks down. He cheats the strong, he robs and dominates the weak […]

The Black Album, then, is split between the personal and collective, the micro and macro, her Jewish ethnicity and Polish nationality, her desire to recount her own experience and her obligation to record the experiences of the murdered. In this sense, Nadel’s mode of graphic storytelling using “image-texts of witness” figures what Tahneer Oksman calls an “art of loss,”33 not only in its depiction of the traumatic loss of life, home, country, language, and history but in its elliptical authorial voice and fractured syntax.

“The Risk of Representation”

Over the last year, I have scoured the archives looking for early postwar graphic narratives drawn, painted, and printed after the Holocaust by survivors.34 Nadel was not the only Jewish woman artist “first responder.”35 In Budapest alone, five postwar albums were created: Ágnes Lukács’s The Auschwitz Women’s Camp in 1946; Edith Bán Kiss’s Deportation Album in 194536; Mariá Turán Hacker’s Metamorphosis, begun in Dachau but completed in Budapest between 1944-5; Gitta Gyenes’s The Antifascist Series of 1944; and Zsuzsa Merényi’s picture diary begun in Bergen Belsen and completed in Budapest, between 1944-1945. To these we should add albums created by Polish women: Regina Lichter-Liron’s Album 1939-1945 completed in Florence in 1946; Zofia Rosenstrauch’s Auschwitz Women’s Camp created in Warsaw in 1945; Luba Gurdus’s They Did Not Live to See published in New York in 1949; and perhaps the most extensive project, Ella Liebermann Shiber’s series of 93 drawings begun in the Karolos DP camp in Cyprus and completed in the first years after her arrival in Israel and later published as Out of the Abyss.37

The Black Album was an epiphany for me: a moment of discovery that opened up a hitherto largely ignored corpus of works from the immediate postwar period that use images and texts to construct graphic narratives of loss. This one album alerted me to the fact that other such works are still out there waiting to be discovered in institutional archives and in private or family collections.

How can we find these graphic narratives? Working forwards, we can begin by identifying artists, like Nadel, who created during the Holocaust, with the assumption that they very often continued the practice afterwards. Working backwards, we can search for survivors who created art much later and contact their descendants for works they may have made immediately after the war. Most important, we can comb institutional archives for individual works on paper made after the war and ascertain if they belonged to a series and then try to reconstitute it. All of this depends, of course, upon access, which has been notoriously difficult in art collections. To wit: the Yad Vashem art archive boasts over 10,000 works, but it is still not digitally accessible to the researcher outside the museum. Add to this the steep reproduction costs that further gatekeep these works from the public.

But the very questions we ask will determine what we find. The challenge of finding these albums is complicated by the lack of proper terminology to identify these works in the archive; depending on the collection where they are held, and their systems of cataloguing, they can be inventoried as “art” or “portfolio” or “album” or “folio” or “book.” When I contact collections looking for such objects, I am shuttled from one department to the next. In some institutions, they are inventoried as unique artifacts in the artifacts division; in others they are preserved as prints in the art collection−in both cases, stored under lock and key in temperature-controlled vaults. In others, they are inventoried as books and pamphlets, either in the rare book collection or in the circulating library. These hyphenated things (art-books, pictorial-albums, image-stories, visual-testimonies) fall between the cracks of the Holocaust archive and its well-entrenched categories of format, medium, subject and periodization. They raise problems of taxonomy because they don’t fit neatly into preexisting search keywords nor obey disciplinary boundaries. In so doing, they prompt questions about how the archive was assembled in the past and how archival practices today assign and maintain hierarchies of value that determine which things count as evidence or testimony. Originals are favored over “photographic reproductions.” Separate works of art are privileged over “books” which are more difficult to exhibit and reproduce. Works made “in real time” during the Holocaust, are prized over those made in its aftermath. In her article on Nadel’s Images from Home, Renata Piątkowska argues that wartime graphic narratives “should be incorporated into scholarship” as valuable visual testimonies, in “no way secondary to written texts from this historical moment.”38 Nadel’s The Black Album urges us to extend this project to postwar graphic narratives.

“Women, Comics and the Risk of Representation” is the title of Hillary Chute’s introduction to her book on contemporary graphic narratives by women.39 The Holocaust graphic narrative, however, is not only a belated medium of intergenerational transmission and vicarious postmemory. As Nadel’s Images from Home and The Black Album demonstrate, during and immediately after the Holocaust, women turned to sequential image-texts to narrativize their personal and collective experiences during the Holocaust. For these women, the “risk of representation” entailed more than conceptual or aesthetic problems of what to draw and how to draw it. The obstacles they faced went beyond the difficulty of self-expression and the dangers of self-exposure. Risk was something these women had faced intimately, profoundly, not as an abstract concept but as part of their daily, lived experience over many, many years under Nazi oppression. And even after the war, their risks were many, given their under-representation in a male-dominated art world and male-dominated postwar Jewish organizations, such as the Historical Commissions, with their entrenched gender roles. They faced, first and foremost, material and practical challenges and physical and financial hurdles: access to supplies (paper, ink, watercolor or tempera paints, brushes and pencils) and the money to purchase them, a quiet place to work, and, above all, the commodity of time to devote to executing these projects, given their need to work and support themselves and their families. And they labored under crushing grief as they started from scratch in foreign cities, uprooted from their homes and homeland, mourning family and loved ones.

That Nadel undertook her project without financial or institutional support is nothing short of remarkable. That she then copied her album, in a size small enough to fit in a back pocket, speaks to her desire to share her work with others: for it to travel and circulate in new places and reach new audiences. Historians have insisted that during this early postwar period, the survivors were so busy focusing on the “pressing problems of food, health, shelter, clothing, the search for family and a safe future”40 that artistic projects were, at best, frivolous distractions from nation building or the work entailed in the “return to life.” Nadel’s Black Album pokes holes in the prevailing view that Holocaust survivors only came forward belatedly, during what Annette Wieviorka calls the “era of the witness,” to “show and tell” their stories.41 It offers a crucial corrective to the pervasive myth of silence regarding the immediate postwar period but extends the growing research on the first decade to the field of artistic production.42 And it exposes another historiographic “silence”−regarding early postwar art created by women.

Acknowledgments

This essay is part of a manuscript in progress entitled Who Will Draw Our History? Early Postwar Holocaust Graphic Narratives which is funded by an EHRI Conny Kristel Fellowship and a Hadassah Brandeis Institute Fellowship. For his help, I thank Eli Eshed, whose conversations on comics and book illustrators in Israel, was invaluable. At the USHMM, I thank Kyra Schuster who helped me get access to the digital file. At POLIN, my thanks to Klara Jackl. For access to archival materials, I acknowledge the incredible generosity of Elisheva Landau’s sons, Michael and Ronny, who graciously shared their mother’s album with me and allowed me to reproduce it here for the first time.

- Nadel’s title in Polish, Z czarnej teki, translates as “From the Black Album” or “Portfolio.” For concision, I will be referring to it throughout as the Black Album. ↩

- Elżbieta Nadel, Z czarnej teki 1939-1945, Praga, 1946. USHMM Rare Books – Shapell Family Collections and Conservation Center, Library Call Number: N7255.P63 L334 1946. 19 unnumbered leaves of photographic reproductions mounted on black Bristol cards (the original is numbered on the backs), 14 cm. Digital files. USHMM, Internet Archive, 2016-12-19. Electronic version(s) available internally at USHMM, Rare Books-Shapell Center.https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/bib250954. The album consists of 19 photographic reproductions mounted on black cards. The initial card identifies the artist and work; the second card offers an index, listing the titles of the 17 artworks reproduced on the remaining cards. ↩

- Wiesław Dyląg, an art dealer, discovered it in a suitcase belonging to his aunts that had not been opened since the war. In 2012, it was presented at the State Museum at Majdanek, and three years later at the Artissima Auction House in the exhibition “From the Shtetl to Paris.” The POLIN Museum purchased the album in 2019, thanks to a grant from the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute. See Tomasz Urzykowski, “One day in the life in the ghetto. A unique work in Polina,” 02/09/2019. https://warszawa.wyborcza.pl/warszawa/7,54420,24442691,jeden-dzien-z-zycia-w-getcie-unikatowe-dzielo-w-polinie.html?disableRedirects=true ↩

- It was purchased by POLIN in 2019. See Tomasz Urzykowski, “One day in the life in the ghetto. A unique work in Polina,” 02/09/2019. https://warszawa.wyborcza.pl/warszawa/7,54420,24442691,jeden-dzien-z-zycia-w-getcie-unikatowe-dzielo-w-polinie.html?disableRedirects=true ↩

- Renata Piątkowska, “Elżbieta Nadel’s Images from Home: 18 Sketches from Nature, Lvov, 1942,” MIEJSCE, June 2020. http://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/english-elzbieta-nadels-images-from-home-18-sketches-from-nature-lvov-1942/: Accessed 11 September 2022. ↩

- https://polin.pl/en/news/2019/01/23/polin-museum-collection-elzbieta-nadel-images-from-home-18 ↩

- I subsequently found a reference to The Black Album in the exhibition catalogue Elżbieta Nadel. Home pictures – Lviv 1942, Galeria Dylag, 2012. ↩

- Email with USHMM archivist, May 2022. ↩

- It was described as “Reproductions of Holocaust-Themed Paintings by Elżbieta Nadel,” Lot 337. (17) cards with reproductions of paintings + (2) cards (title page and list of painting titles), 13.5X9.5 cm. https://www.kedem-auctions.com/en/content/reproductions-holocaust-themed-paintings-elzbieta-nadel-%E2%80%93-prague-1946. I haven’t been able to ascertain who put it up for auction. ↩

- The term “picture stories” is Jörn Wendland’s. See his “Picture stories from prisoners of the concentration and extermination camps. Continuity and change in function, iconography and narration before and after 1945,” in: Christiane Heß / Julia Hörath et al. (Eds.): Continuities and breaks. New perspectives on the history of the Nazi concentration camps (Berlin 2011), pp. 142–164. ↩

- The term “imagetext” was formulated by W.J.T. Mitchell. See Christine Wiesenthal, Brad Bucknell and W. J. T. Mitchell, “Essays into the Imagetext: An Interview with W. J. T. Mitchell,” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, Vol. 33, No. 2 (June 2000): 1-23. ↩

- Her name, listed as Alzbeta Nadel, appears in a case file of survivors served by the AJDC Emigration Service in Czechoslovakia after the war, alongside that of her mother, Regina Nadel, and Mose Lublinsky, a painter who figures in the archives of the Jewish Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts as working in Lódź in an association of Jewish painters called Co-operative of Painters “Art” (Spółdzielnia Pracy Artystów Malarzy “Sztuka”). See AJDC Prague Office Case File Index, 77: https://archives.jdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AJDC-Prague-Emigration-Case-File-Index.pdf ↩

- Nadel supposedly also made another album during the time she worked with her mother as a nurse in German hospitals, although I have yet to see it. ↩

- Eli Eshed, אלי אשד: https://www.no-666.com/2022/04/12/%d7%a6%d7%99%d7%99%d7%a8%d7%aa-%d7%94%d7%a7%d7%95%d7%9e%d7%99%d7%a7%d7%a1-%d7%94%d7%a2%d7%91%d7%a8%d7%99%d7%aa-%d7%94%d7%a8%d7%90%d7%a9%d7%95%d7%a0%d7%94-%d7%a1%d7%99%d7%a4%d7%95%d7%a8%d7%94-%d7%a9/ ↩

- Haaretz Shelanu ran two articles devoted to her when she retired from the weekly after 31 years on March 26 and 27, 1982. Perhaps the only story about the Holocaust she illustrated was by Esther Streit-Wurtzel, אסתר שטרייט-וורצל, From the Straits, 1962 (מן המצר). The book deals with Jewish heroism in the Holocaust. The plot of the book Man Hatzer presents the story of a Jewish family in the Holocaust. During the story, the parents are forcibly separated from their children by the Germans, Sasha and Roja, but during the story the mother meets her children in one of the remote villages in Poland. ↩

- The word “lipiec” (July) is inscribed on the envelope. I discuss Nadel’s Images from Home in my essay “Drawn Out of Horror: Early Holocaust Graphic Narratives by Jewish Women Witnesses” in Drawing Memory in Jewish Women’s Graphic Novels, ed. Victoria Aarons (Wayne State University Press, 2023). ↩

- Frances Yates, The Art of Memory (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966). ↩

- Alexandra Garbarini, Numbered Days: Diary Writing and the Holocaust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006). ↩

- Laura Berlant, Cruel Optimism: Symbols, Allegory and Motifs (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), p. 5. ↩

- Imke Hansen et al. “Fremd-und Selbstbestimmung im Kontext von nationalsozialistischer Verfolgung und Ghettoalltag,” in Lebenswelt Ghetto. Alltag und soziales Umfeld während der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung, edited by Imke Hansen, Katrin Steffen, und Joachim Tauber (Harrassowitz Verlag, 2013), p. 8. ↩

- According to her sons, she illustrated two books in Lviv before Images from Home: Charles de Coster’s The Brotherhood of the Cheerful Countenance (five colored linocuts in 1941) and Alain-René Lesage’s 1707 Lame Devil or The Devil Upon Two Sticks (11 illustrations 1942) earlier illustrated as a satire by James Gillray. ↩

- Kazimierz Moździerz was acknowledged as a Righteous Among the Nations because of her testimony. Kwestionariusz świadka Elishevy Landau z 15 czerwca 1987 r. (Questionnaire for Witness Elisheva Landau, June 15, 1987), 1. Dossier for “Moździerz Kazimierz,” ŻIH Archives, sig. Yad Vashem—349/24/1043, 2-3. ↩

- Kazimierz Mozdzierz and his sister Helena were awarded the honor in 1989, thanks to Nadel’s application in 1987 (4219 1989). https://zyciebytomskie-pl.translate.goog/index.php/ZB/panteon/kazimierz-mozdzierz-sprawiedliwy-wrod-narodow?_x_tr_sch=http&_x_tr_sl=pl&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc. Moździerz helped another woman, Yala Korwin, born as Jala Meisels (1933-2014). She was a poet, artist, author, essayist, librarian and teacher. https://qns.com/2008/05/survivor-profile-yala-korwin/ ↩

- In her dossier for Moździerz in 1987, she writes: “After the Great Action in Lvov in August, 1942 (when my 16-year old brother died), my parents and I left for Warsaw, where I lived under ‘Aryan papers’ (father died) until the Polish uprising. We managed to get to Warsaw thanks to Kazimierz Moździerz, who escorted us there at the risk of his life and helped us find an apartment. We stayed in Warsaw until the Polish uprising and its defeat in 1944, when we fled to Pruszków, living out what remained of the war in this little town outside of Warsaw. There, we worked as nurses in a hospital for the wounded. In Warsaw, we supported ourselves by making macramé. After the Russians took over the city, and after searching for a family member to no avail, we moved to Prague and eventually onward to Israel in 1948″. Kwestionariusz świadka Elishevy Landau z 15 czerwca 1987 r. (Questionnaire for Witness Elisheva Landau, June 15, 1987), 1. Dossier for “Moździerz Kazimierz,” ŻIH Archives, sig. Yad Vashem—349/24/1043, 2-3. Cit. in Piątkowska, “Elżbieta Nadel’s Images from Home,” endnote no. 7. ↩

- My title riffs on Zoë Waxman’s chapter “Writing to Remember” in Writing the Holocaust : Identity, Testimony, Representation (Oxford University Press, 2007). ↩

- Jennifer Sinor, “Reading the Ordinary Diary,” Rhetoric Review Vol. 21, No. 2 (2002): 123-149, 123. ↩

- Nadel’s title was widely used for Holocaust publications. The Black Book: The Nazi Crime Against the Jewish People published in 1946 was an indictment of the Holocaust submitted for evidence at the Nuremberg Trials. It was prepared in 1946 by the Jewish Black Book Committee, which included the World Jewish Congress; the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, USSR; Vaad Leumi, Palestine; and the American Committee of Jewish Writers, Artists, and Scientists. ↩

- In Polish, the index reads: Spis 17 klepsydr tuszem

Herrenvolk and Untermenschen

Co zawinili

Na ulicy

Dwie opaski

Do pracy

Przeprowadzka

Po tamtej stronie

Obrazem z getta

Dzieci

„Akcja”

W ukryciu

W oczekiwaniu

Droga śmierci

Nowoczesna „folterkammer”

Ludzie-cienie

Samobójcy

To byli ludzie… ↩ - Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York, NY: Harper Paperbacks, 1993), p. 63. McCloud defines closure in comics as “observing the parts but perceiving the whole” a process through which “the audience becomes a willing and conscious collaborator and closure is the agent of time and motion” (p. 65). ↩

- Michael Rothberg, Traumatic Realism: The Demands of Holocaust Representation (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000). See also Zoë Waxman who notes that in early written testimonies, “The nature of trauma means that the experiences of survivors are resistant ultimately to any final narrativization.” Writing the Holocaust: Identity, Testimony, Representation (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 119. ↩

- See Mor Presiado, “The Expansion and Destruction of the Symbol of the Victimized and Self-Sacrificing Mother in Women’s Holocaust Art,” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 33 (2018): 177–208. ↩

- “Jency” (Captives) takes place in a 10th century German village on the Slavic lands between Oder and Elbe rivers. It was performed in 1945 in Lublin, Teatr Miejski w Lublinie: (Lublin : s.n., 1945): https://polona.pl/item/program-inc-lucjan-rydel-jency-odslon-trzy,NjA4NTcyODA/1/#info:metadata and again in 1947 at the Teatr Polski Towarzystwa Teatru i Muzyki Ludowej w Lęborku. My thanks to Agata Pietrasik for help with the translation and sources. ↩

- Tahneer Oksman, “An Art of Loss,” in Spaces Between: Gender, Diversity, and Identity in Comics, eds. Nina Eckhoff-Heindl and Véronique Sina (Springer VS Wiesbaden, 2020), pp. 187-200, p. 192. ↩

- Erik Reidel discusses a few postwar portfolios in his essay “Art Prints as a Medium for the Documentation and Memorialization of the Genocide” in Our Courage. Jews in Europe 1945‒48, eds. Kata Bohus, Atina Grossmann, Werner Hanak and Mirjam Wenzel (Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2020), 56-63. My interest in these works was prompted by Kathrin Hoffmann-Curtius who covers a few postwar “series” made in Germany in her book Judenmord: Art and the Holocaust in Post-war Germany (London: Reaktion Books, 2018). See my forthcoming articles on the subject: “Who Will Draw Our History?Early Holocaust Graphic Narratives as a Minor Art,” in Survivors’ Toil: The First Decade of Documenting and Studying the Holocaust, Simon Wiesenthal Center, Vienna (Summer 2023); “Making Holocaust Mementos: Early Postwar Graphic Albums as Awkward Objects of the Holocaust Archive,” for special issue on Awkward Objects, Curiosa and Varia: Exploring the Boundaries of the Holocaust Archive,Holocaust and Genocide Studies (Fall 2023). ↩

- Tracking postwar artists is complicated by the fact that they often took different names after they immigrated to their new countries of residence. But women not only anglicized or Hebraicized their names; they also took new last names when they married. Zofia Rosenstrauch, for instance, the author of the Auschwitz Women’s Camp album, changed her name after the war to Naomi Judkowski when she married Boria Judkowski and moved to Lohamei Haghettaot in Israel in 1948. See Naomi Judkowski, Requiem for two families (Ghetto Fighters House, 1990). For her remarkable biography, see https://sztetl.org.pl/en/biographies/195756-rozensztrauch-zofia-judkowski-naomi. My thanks to Agata Pietrasik for finding this source. ↩

- See Helmuth Bauer, Innere Bilder wird man nicht los:die Frauen im KZ-Aussenlager Daimler-Benz Genshagen(Berlin:Metropol Verlag, 2011). ↩

- Lea Grundig also made an album with nine plates in 1942-3 in Mandatory Palestine that was published as BeGey HaHarigah (In the Valley of Slaughter) (Tel Aviv: Haaretz Press, 1944)and then republished in German in Dresden in 1947 as Im Mal des Todes. ↩

- Renata Piątkowska, “Elżbieta Nadel’s Images from Home“. ↩

- Hillary Chute, Graphic Women: Life, Narrative and Contemporary Comics (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010), pp. 1-27. ↩

- Zeev W. Mankowitz, Life between Memory and Hope: The Survivors of the Holocaust in Occupied Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,2002), pp. 3–4. ↩

- Annette Wieviorka, The Era of the Witness (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006). The research of Zoë Vania Waxman and Sharon Klangsinger on written testimonies likewise challenges the traditional notion of a pervasive postwar silence regarding the survivors’ experiences. See Waxman, Writing the Holocaust: Identity, Testimony, Representation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008) and Klangsinger, Testimony and Time: Holocaust Survivors Remember (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2014). ↩

- For scholarship on survivors in the first decade, see Atina Grossmann, Jews, Germans, and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007); Laura Jockusch, Collect and Record! Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe (Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress, 2012); Angelika Konigseder and Juliane Wetzel, Waiting for Hope: Jewish Displaced Persons in Post-World War II Germany (Northwestern University Press, 2001); Zeev W. Mankowitz, Life Between Memory and Hope: The Survivors of the Holocaust in Occupied Germany (Cambridge University Press, 2002); Leah Wolfson, Jewish Responses to Persecution: 1944–1946(Documenting Life and Destruction: Holocaust Sources in Context Book 5) (USHMM and Rowman and Littlefield, 2015). On historiography debates regarding the “myth of silence” after the Holocaust, see François Azouvi, Le Mythe du Grand Silence: Auschwitz, les Français, la Mémoire (Paris: Fayard,2012); David Cesarani and Eric J. Sundquist, eds., After the Holocaust: Challenging the Myth of Silence (London: Routledge, 2012); andHasia Diner, We Remember with Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence after the Holocaust, 1945–1962 (New York:New York University Press, 2009); Philip Nord, After the Deportation: Memory Battles in Postwar France (Cambridge University Press, 2020); and Simon Perego, “Memory before memory? Looking back on the historiography of Holocaust memory in postwar France,” 20 & 21. Revue d’histoire, vol. 145, Issue 1 (2020): 77-90. ↩

Ezra

fascinating and extremely well written!

Marianne Windsperger

Thank you so much for this text that addresses questions of transmission, classification, categorization, search-ability and find-ability via presenting this early postwar album and drawing attention to silences in research and documentation!

Renata

Fascinating. Thank you.