For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

Archive files of criminal cases are a rather specific type of historical sources. In Ukraine, they can be found either in the Sectoral State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) in Kyiv1 or in regional SBU archives in the oblast capitals. A small number of these materials have been transferred to the state oblast archives, which are not part of the SBU structure. Due to this fact, access to these files was, until 2015, restricted for most researchers. Only recently have they become freely available for research. Today, digitized copies of some criminal cases are available on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, as well as in the Yad Vashem’s archive. Therefore, it is important and necessary to introduce these files to a wider scholarly public. All the more so because the first 100 days of the Russian invasion have led to the destruction of various collections, among others in SBU archives. And it is impossible to say whether more documents will be destroyed. Therefore, one of the aims of this research, besides shedding light on the Holocaust in the city of Kryvyi Rih and its environs, is to preserve information about these sources.

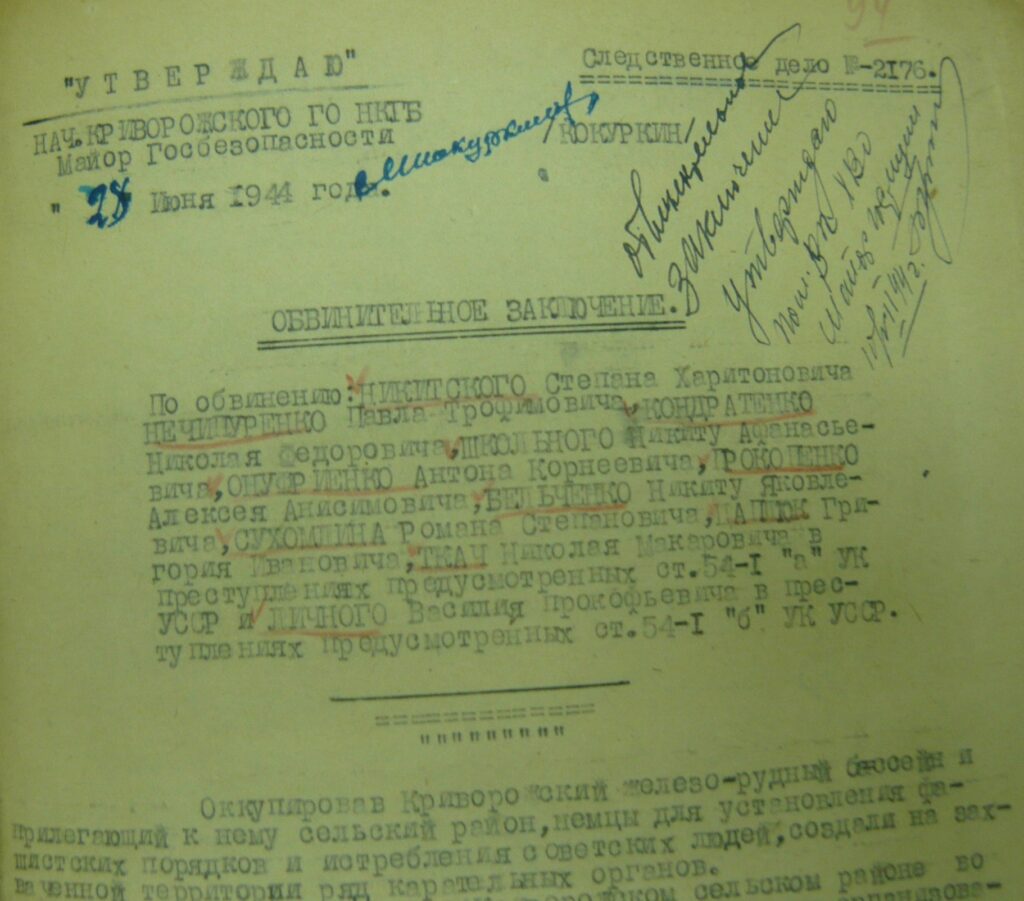

The majority of Soviet investigation files on Kryvyi Rih policemen are located in collection 6(R) of the SBU Archive in the city of Dnipro, the oblast capital. The documents in these files differ in terms of information density, but among other things, they contain materials concerning the genocide of the Jewish population of the city. They provide a picture of the largest “action” to eliminate the Jews of Kryvyi Rih, which took place in October 1941, as well as of individual cases of Jews being killed or arrested. Moreover, these documents allow one to study the motives of those who joined the apparatus responsible for the Holocaust and to identify various groups – the people who were directly involved in guarding and convoying the Jews to the mass shooting site in October 1941, those who participated in the plundering and distribution of Jewish property, as well as the individuals who ordered the “action”. From time to time, the files on policemen feature names of Jewish individuals who were arrested and whose fate is unknown, or who were murdered. This kind of information makes it possible to establish the names of the victims of the Catastrophe (as the Holocaust is also called in Ukrainian and Russian) in Kryvyi Rih.

Most of the investigation files on Kryvyi Rih policemen from the archive stem from the years 1944-1955. The number of suspects varies from case to case (concerning one person or a group), as does the number of volumes. All of them, however, follow the standard Soviet procedure of conducting investigations, meaning that, as the well-known researcher Ivan Dereiko has justly remarked, their structure and systematization, are analogous to those of cases from the 1920s and 1930s known from literature, when the criminal code and criminal procedure code first gained force. And therefore, the investigation files in question can be subdivided as follows:

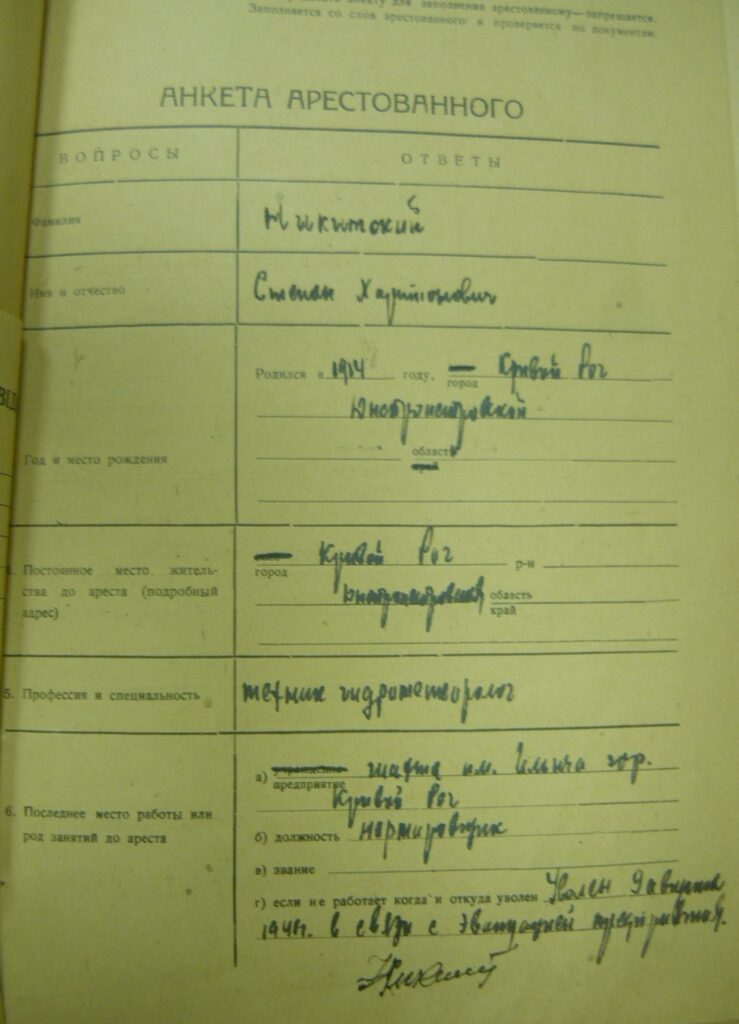

1) arrest and search documentation: decision on measures of restraint, search warrant, search report, receipt for the transfer and storage of seized items, description of the property, questionnaire of the arrested person, testimonies of those involved concerning the circumstances of arrest (in case the arrested person resisted).

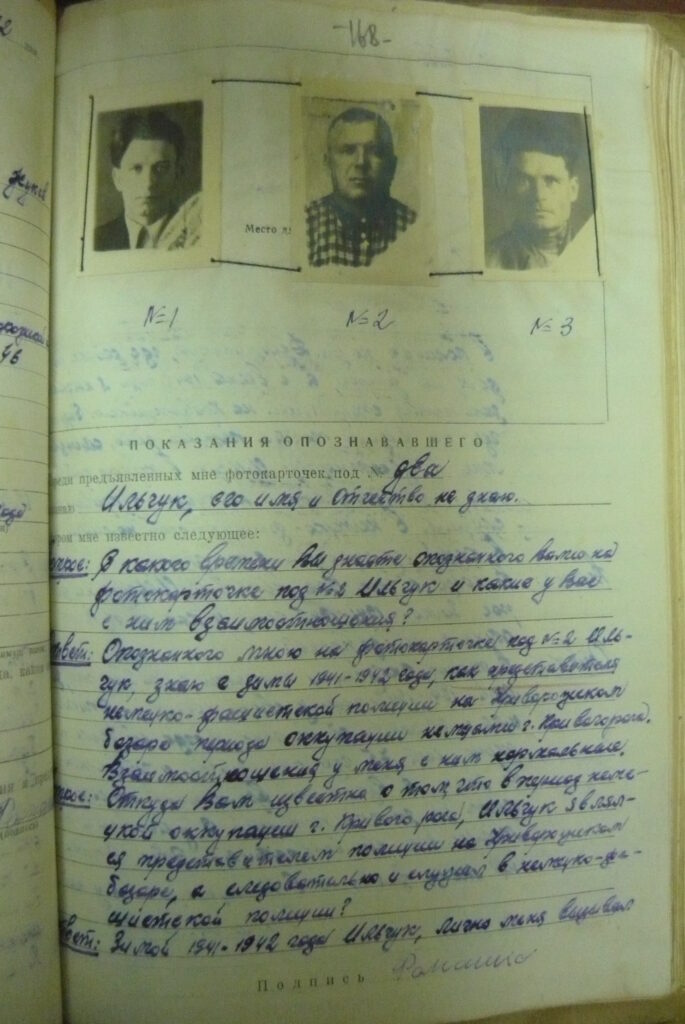

2) investigation materials: interrogation records of the accused and the witnesses, confrontation records, personal testimonies of the accused, materials from investigations into the activities of other suspects who served in the same unit or department, decision on the charges, adjustment of the measures of restraint.

3) external documentation: materials acquired by the NKVD and NKGB (MVD and MGB/KGB) in response to official requests to various institutions to determine the identity and activities of the accused, and in which units and departments they served – certificates, references, characterizations from their place of residence, employment or service; materials from on-site investigations into violence or repression against the population; internal documentation from their superiors and adversaries (in case of measures against state-sponsored partisan platoons or Red Army units). In the materials of this category, there is very little information about the Holocaust. From them, we can learn about the motives of the criminals, the facts of their biography, which they did not tell during the investigation, etc. In general, this group of materials requires more research.

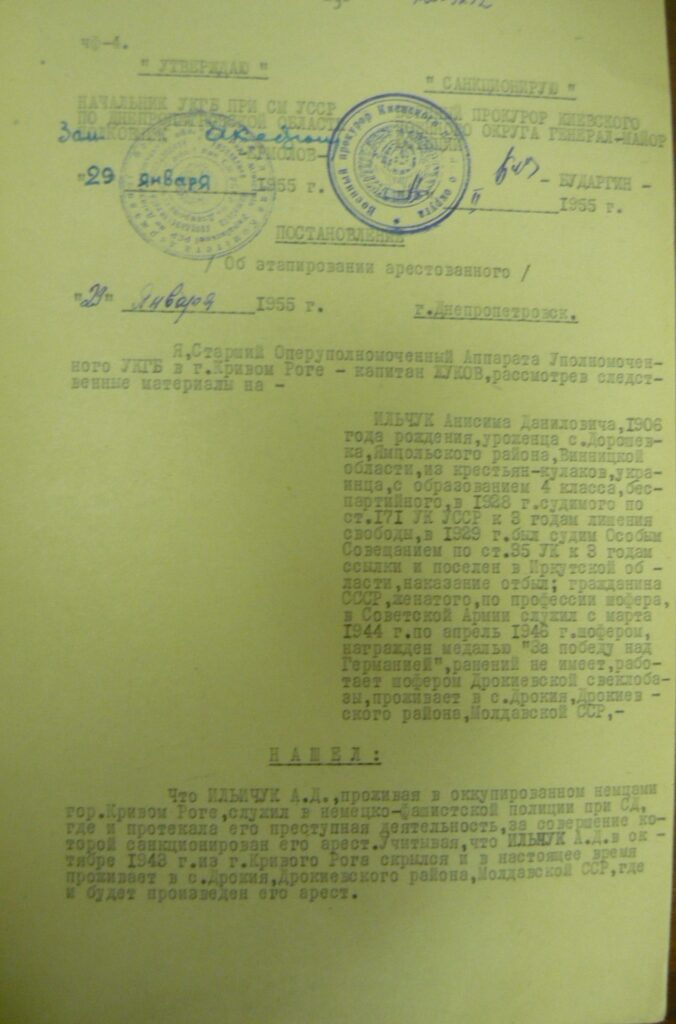

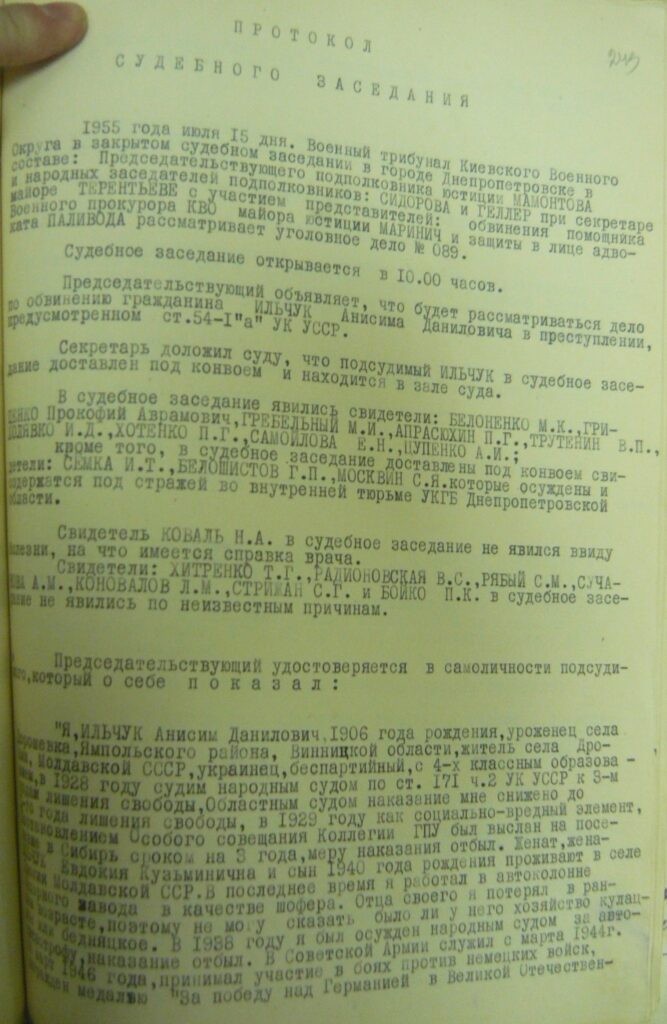

4) trial documentation: record of submission of investigation materials, indictment, conviction by the court (or extrajudicial body, tribunal, etc.), hearing records of the Special Council concerning repression of the defendant’s family members.2

Arrest and search documentation

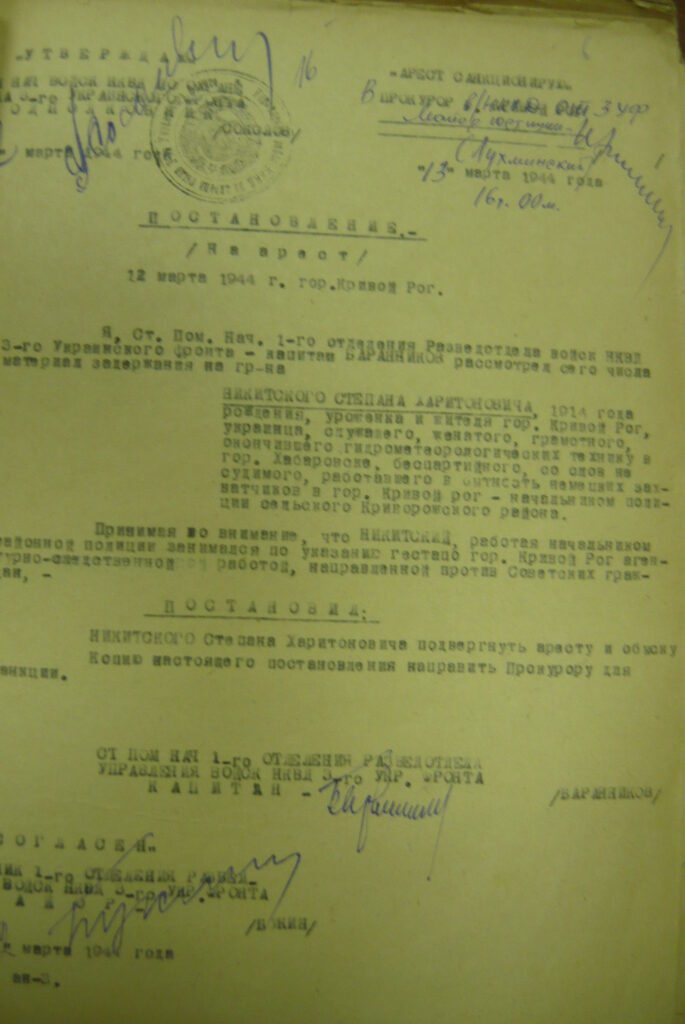

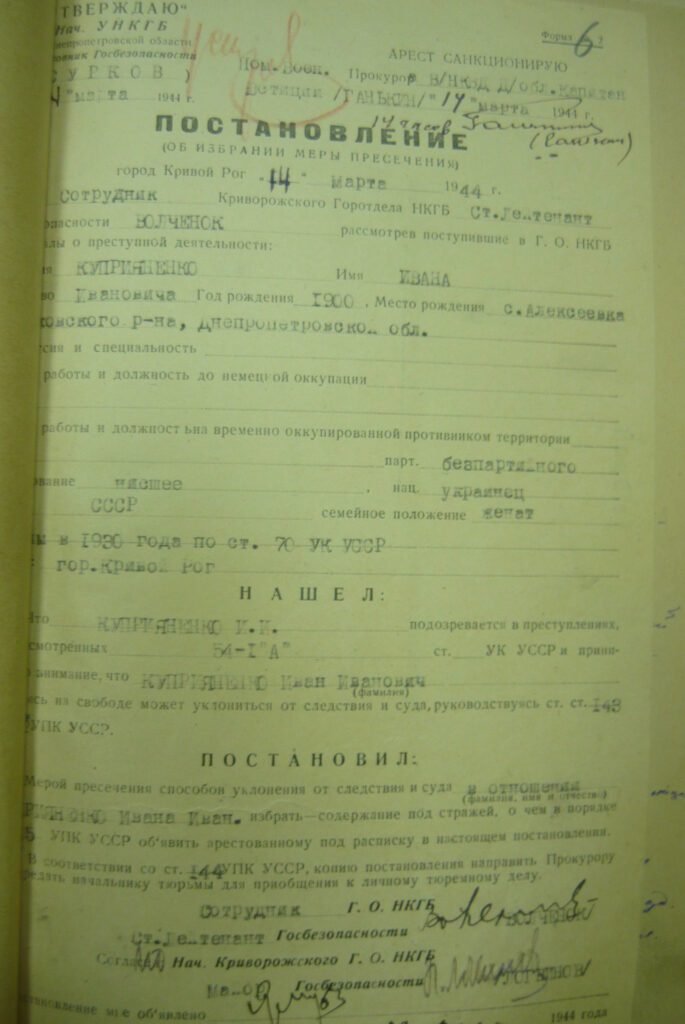

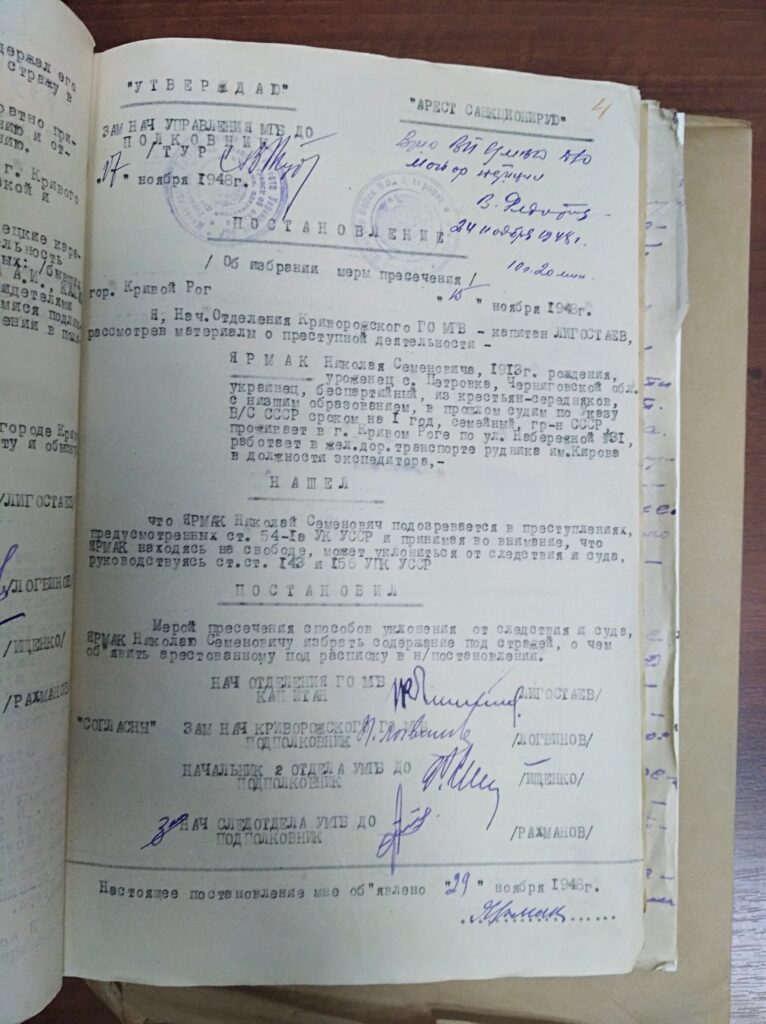

The first document of an investigation file in which crimes against the Jewish population may be mentioned is the decision on measures of restraint, referred to as ‘Arrest warrant’ in the files. In case a file consists of materials on more than one individual, then the arrest warrants, as a rule, can be found at the start of each individual section in the file. The information contained in the decisions on measures of restraint was acquired during interrogations by NKVD-MVD officers or via their network of informants and agents. Thus, the exposition of the crime is, on the one hand, strictly informative, but on the other, it plays a key role in the development of the investigation, since the investigator, during the interrogations, will be first and foremostly guided by the accusations put forward in the arrest warrant.

In the majority of investigation files on Kryvyi Rih, policemen disclosed for the purpose of this survey, the decision on measures of restraint contains information about Holocaust-related crimes. As a rule, this document can be subdivided into two parts, in terms of the type of information. The first part presents biographical information about the suspect. This allows one to deduct the social status of the individual in question, their education and in some cases even the motives behind their cooperation with the German repression apparatus. For example, the arrest warrant of local policeman Petro Holovatyi, specifies that he came from a background of “kulaks” (wealthy peasants) and finished 7 school classes, and that his father had been repressed.3 The social background of Holovatyi and the repression of his father by the Soviet authorities, as well as his low level of education, were arguably among the main reasons for his enlistment in the local police.

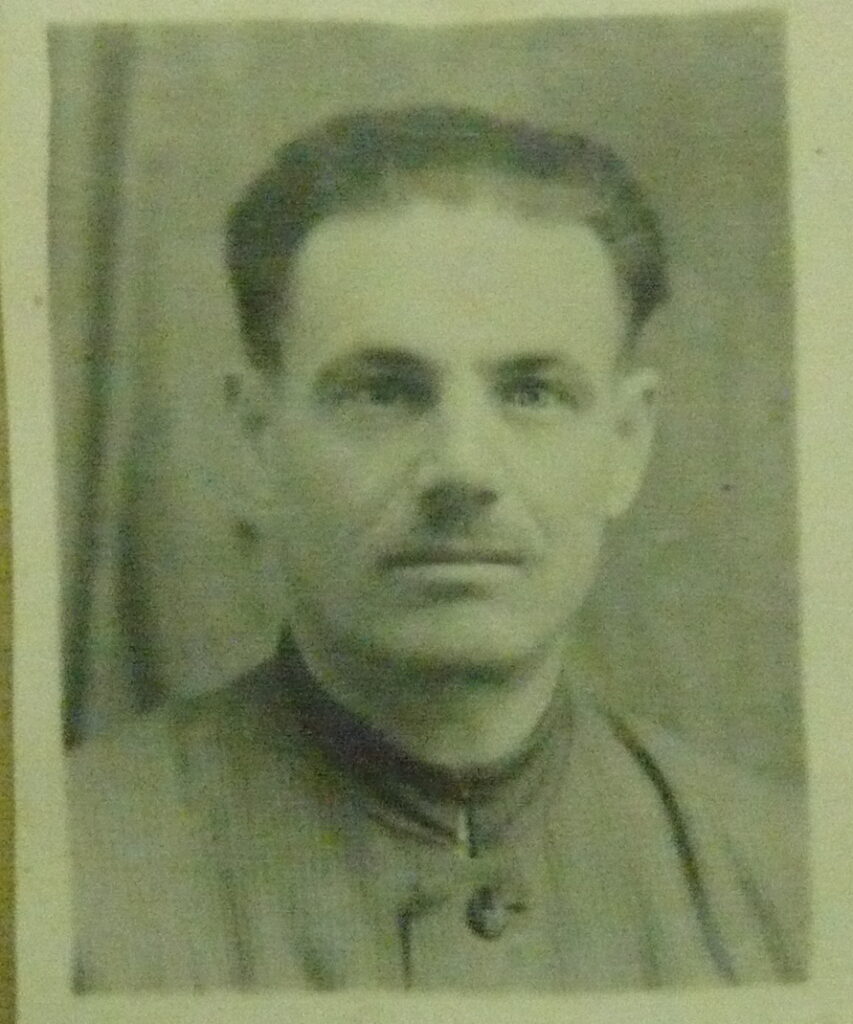

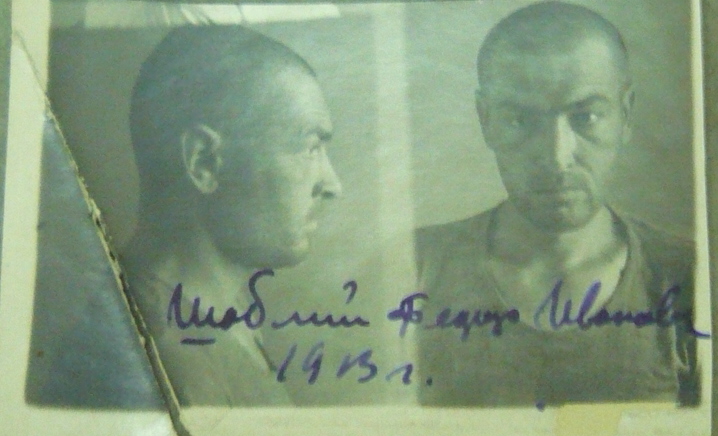

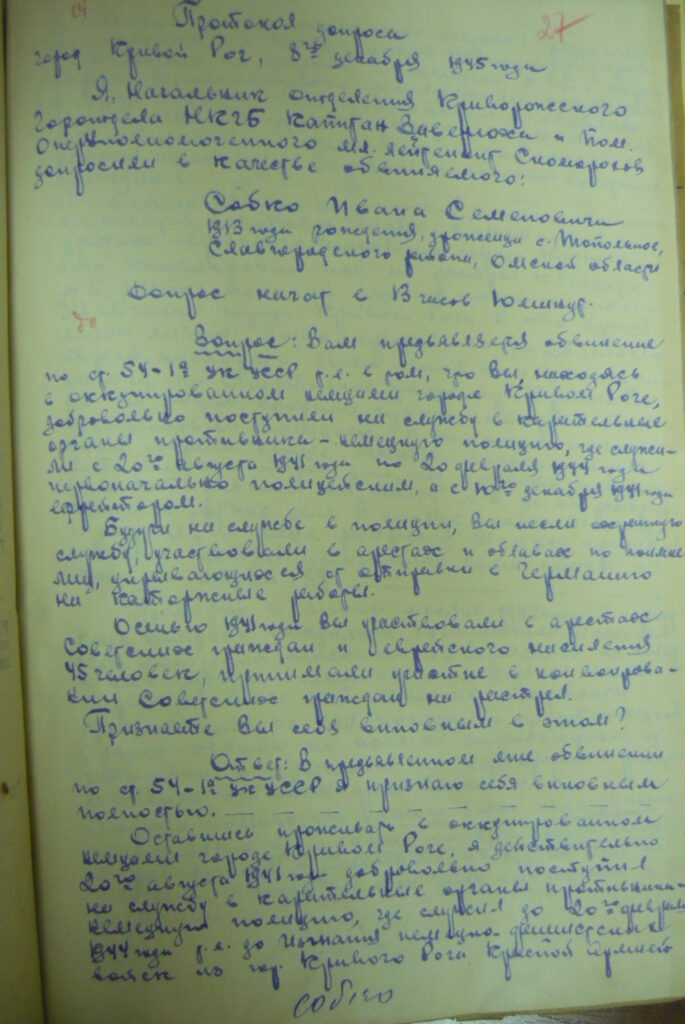

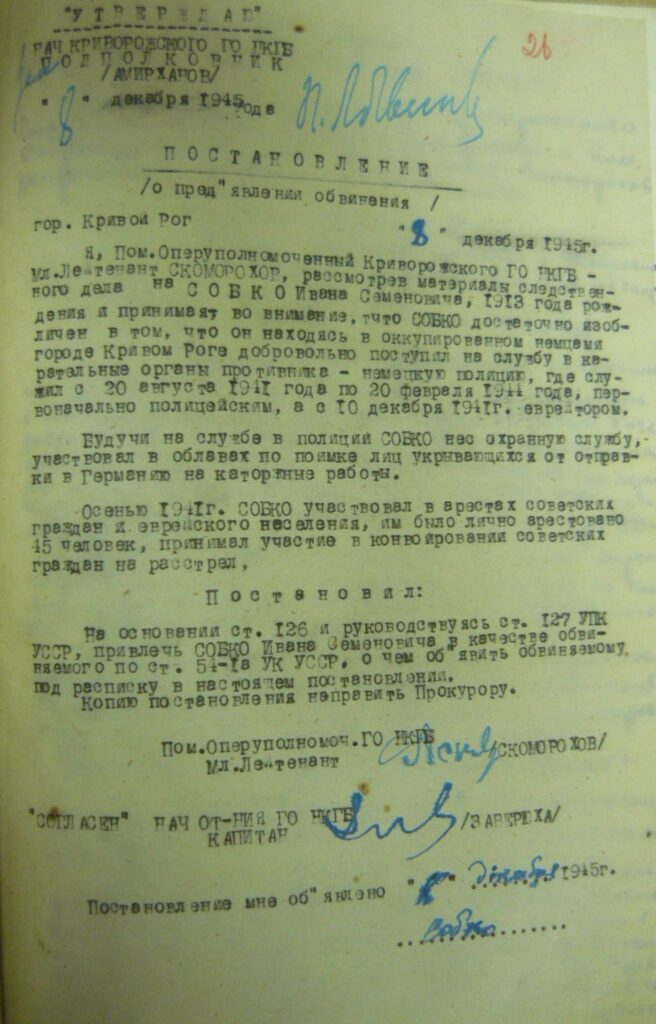

The second part outlines the suspicion put forward by the Soviet state security bodies and the criminal activities confirming this suspicion. In the majority of cases against Kryvyi Rih policemen, the arrest warrant already contains information about their participation in the mass shooting of the Jewish population of the city. This very phrasing features in the decisions on measures of restraint on the policemen Ivan Kupriianenko4, Fedir Shablii5, Vasyl’ Lysenko6, Semen Petrichenko7, and others. These cases date back to the second half of the 1940s, and interestingly enough, despite the prevailing view at that time that it was ‘peaceful Soviet citizens’ (without regard for their ethnicity8) who died at the hand of the Nazis, these documents clearly indicate that the individuals in question participated in the extermination of the Jewish population. One exception is the arrest warrant in the investigation file on another local policeman, Ivan Sobko9. This document is dated December 1945, and one of the crimes Sobko is suspected of is his participation in arrests of ‘Soviet citizens’. However, based on the materials of the criminal case, we know that Sobko in fact was directly involved in the anti-Jewish action of 14 October 1941, about which he testifies in ample detail. Highly informative is the arrest warrant of Ivan Kalashnyk, who served as the storage manager of the local police force starting from November 1941. According to the decision, he had at his command six Jewish individuals, who he constantly abused and forced to work for him. Moreover, in the course of February and March 1942, he beat up arrested Jews prior to their shooting.10 Such a detailed description of crimes is an exception rather than the norm for investigative cases initiated in the second half of the 1940s. Because most of the materials of criminal cases of the first post-war years are characterized by low professional quality of design.

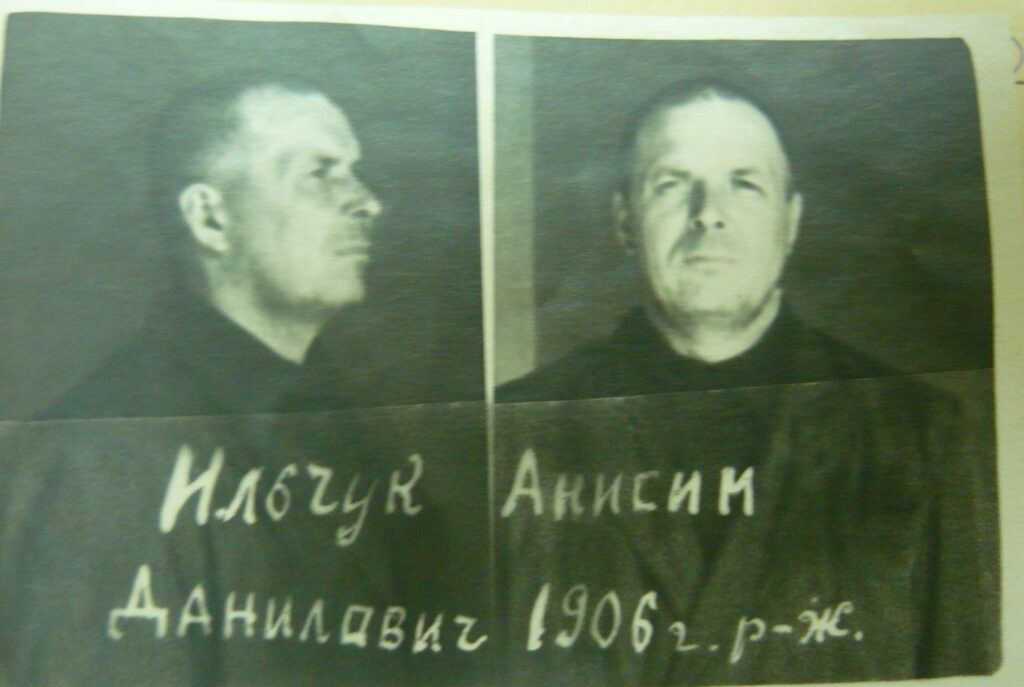

Of higher professionality are the criminal cases conducted by security officers against local collaborators in the 1950s. For instance, in the decision on measures of restraint concerning Anisim Il’chuk, his criminal activities are presented concretely. In particular, it is mentioned that he ordered policemen to collect the valuables of the shot Jews from the shooting site (the site in question was mine shaft No. 5, where on 14 October 1941, around 2500 Jewish residents of Kryvyi Rih were shot, as well as 800 POWs of predominantly Jewish ethnicity), which they had to hand over to a German officer. Moreover, in November and December 1941, Il’chuk used physical violence to force S. Moskvyn and I. Kholiavko to confess that their wives – M. Vinar-Moskvyna and Kh. Moroz – were of Jewish descent. As a result, Vinar-Moskvyna was arrested and shot together with her infant child, while Moroz was able to escape and stay out of hands of the Kryvyi Rih police.11 And in May or June 1942, policeman Oleksii Shkoliar, acting on orders of Il’chuk, arrested E. Kohan and her sons Leonid and Valentyn. They were shot for being of Jewish ethnicity.12 Thus, the information contained in the arrest warrants provides an idea of the severity of the criminal activities of individual policemen.

Clues about the social-political profile and motives of the perpetrators can be found in the document titled ‘Questionnaire of the arrested person’, as well as in the handwritten ‘Autobiographies’ of the arrested contained in some investigation files. An analysis of the questionnaires of some 50 criminal files makes it possible to determine the main features of the social-political profile of the typical Kryvyi Rih policeman. In terms of ethnicity, almost 80% of the policemen from the analyzed questionnaires were Ukrainians.

The education level of the policemen as well as their employment prior to the Nazi occupation have also been analyzed. According to the 1939 all-Soviet census, 12.9% of the population of the Ukrainian SSR had received higher education, and 18% middle education. According to the same census, 15% of people under the age of 50 were illiterate.13 Thus, the majority of the population in the Ukrainian SSR before the Nazi occupation had received either incomplete middle education or elementary education only. As might be expected, a similar picture can be observed among those who enlisted to serve in the German punitive apparatus during the occupation. The majority of the policemen had received four years of school or less – among the analyzed questionnaires they make up nearly 80% of the total. This was the main mass of policemen actively involved in the murder of Jews. They served predominantly in lower or middle ranks. Among the police leadership, by contrast, individuals with higher or middle technical education can be found. To give an example, the head of the Kryvyi Rih Raion police S. Nikits’kyi had completed a technical college and received the profession of hydrometeorologist.14

Thus, the majority of policemen had received incomplete middle education at most, which was entirely typical for Soviet society of the late 1930s. Few individual policemen had received higher education and a profession.

Educational level also determined the range of occupations the future policemen had held prior to the occupation. Of the Kryvyi Rih policemen, 75% used to work as workers at various enterprises before the occupation, and nearly half of them came from rural areas. They had ended up in the city in the course of the 1930s, after the dekulakization and the Holodomor. Only a small fraction of the Kryvyi Rih policemen had served in the military. For instance, Fedir Shablii, the deputy head of the Kryvyi Rih Raion police, had been mobilized into the 7th Battalion of the NKVD Railroad Forces in 1939,15 and Oleksii Pasternak, a ‘security police and SD’ investigator, had served in the Red Army and ended up in German captivity in the summer of 1941. Accordingly, in the rural parts of the wider Kryvyi Rih region, the majority of policemen were former kolkhoz workers and came from families of middle and poor peasants, although policemen from repressed “kulak” families were also to be found.

In terms of political orientation, nearly 95% of the policemen from the analyzed questionnaires were not Party members. Only 5% were Komsomol or Communist Party members, or had some form of relation to the authorities. Mykola Kondratenko, head of the village police in Vesele, Kryvyi Rih Raion, had been a deputy in the Vesela Balka village council, and the aforementioned Nikits’kyi was a Komsomol member.16

Thus, the analyzed details from the questionnaires make it possible to determine that the social-political profile of most policemen, at least in Kryvyi Rih, did not differ from the general social-political ‘face’ of Soviet society in the 1930s. They did not suffer from mental conditions, before the war they had had decent, for Soviet standards, jobs and education, most were no Party members, and prior to the occupation they had not harbored nationalistic views. However, during the Nazi occupation they joined the local police and, according to statements by locals, were ‘more terrifying than the Germans’.

Investigation materials

The richest source of information are the interrogation records of the accused and the witnesses. However, German researcher Tanja Penter has pointed out a number of complications in working with materials of the Soviet special services. First of all, the statements given by the witnesses and accused reflect to a large extent the interpretation of the investigator (as a rule, interrogations were conducted by a single investigator). Therefore, these sources should be studied in combination with other available documents. On the other hand, in many cases the materials of the Soviet special services are the only source containing detailed descriptions of mass shootings of Jews, besides witness testimonies about living conditions in ghettos and camps.17 Moreover, one must take into account that the testimonies of the accused and witnesses are a reasonably reliable source when it comes to the identification and the criminal activities of local collaborators; German perpetrators, however, were often simply called ‘Gestapo’ officers. The German scholar also stresses the importance to keep in mind that investigation materials present the question of cooperation from the viewpoint of the Soviet authorities.18 Thus, the materials are, on the one hand, fairly tendentious sources, but on the other, they can contain highly important and even unique information about crimes against the Jewish population.

There are four different ways to extract details about the Holocaust from the interrogation records of the Kryvyi Rih policemen. These are: (1) determining the range of local actors involved in the Holocaust in Kryvyi Rih; (2) reconstructing the course of events of the largest mass shooting of Jews in the city on 14 October 1941; (3) identifying victims of the Jewish genocide in the region; and (4) studying other criminal activities of the local policemen concerning the Jewish population of the wider Kryvyi Rih region.

Identifying local perpetrators

One of the most important aspects of Holocaust research is identifying individuals who were involved in murdering Jews, either directly or in a supportive role. A substantial number of these perpetrators has been established. Thanks to a collection of documents by the Ukrainian researcher Alexander Kruglov, the German commanders responsible for the mass murder of Kryvyi Rih Jews in October 1941 have been identified.19 It is an established fact that the Germans carried out the shooting themselves. I. Kupriianenko, the head of the 1st police department, testified during his interrogations that an SS unit came over from Dnipro (then called Dnipropetrovsk) specifically for the shooting.20 The other Kryvyi Rih policemen also stated that the shooting was conducted by Germans, although they did not specify the unit in question.

By contrast, the head of the Kryvyi Rih Raion police S. Nikits’kyi stated that the destruction of the Jewish population in the autumn of 1941 was carried out mainly by two auxiliary units. These were the 130th Schutzbataillon and a Cossack squadron (sotnia) headed by Havrylo Bohun. The interrogation record of one of his deputies, Shablii, revealed that the Cossack squadron was formed in September-October 1941. Its ranks were filled with local policemen and Red Army POWs from the local camp.21 The 130th Schutzbataillon, meanwhile, was created in late 1941 – early 1942. The battalion consisted of local police cadres and POWs from Stalag 338, as well as local volunteers.22 Thus these two units, together with the Germans Sonderkommandos, were involved in the annihilation of the Jewish population conducted in Kryvyi Rih in the course of 1941-1942.

Reconstructing the events of 14 October 1941

More is known about the role of members of the auxiliary police in the “action” of 14 October 1941. By order of the German military command of Kryvyi Rih, the entire auxiliary police force had to participate in the extermination of the city’s Jews.23 The interrogation records of local policemen reveal that the policemen took part in arresting Jews on the eve of the murder, in convoying them to the killing site, and in collecting their possessions afterwards. On 13 October 1941, all Kryvyi Rih Jews were driven into the local synagogue, which was located on Sportyvna St. According to policeman I. Sobko, the order to arrest the Jewish population in October 1941 was issued by police head Taranenko.24 Sobko had to arrest Jews on the central street of the city – Poshtova St. He was ordered to do so by Feldwebel Koval’. Together with policeman V. Lysenko, Sobko arrested six Jewish families and brought them to the synagogue. They had to hand over the apartment keys of these families to Koval’.25

The statements by the local policemen reveal that one of Taranenko’s deputies was a man named Vasyl’ Pasternak. After a reorganization of the local police, which was implemented in the winter of 1942, Pasternak came to head the SD investigation department. In the autumn of 1941, during the largest ‘Jewish action’ in the city, he as Taranenko’s deputy had been responsible for gathering the Jews in the synagogue. Moreover, when he became head of the SD department, he, together with his brother Oleksii and another investigator, Mykhailo Strykal, personally drove out to shootings of prisoners.26 It is evident that in 1942 there were also Jews among the prisoners shot by the Germans. According to policeman Henadii Beloshystov, in January-February 1942, the Kryvyi Rih SD regularly held groups of Jews captive in their cellars, who were subsequently shot.27

The statements of A. Il’chuk reveal that after the October 1941 shooting, policeman Mykola Bozhko visited him in his office and handed him a list of 10-15 families of Jewish ethnicity who had to be arrested and handed over to the police. The list consisted of surnames and addresses of Jewish individuals. Il’chuk, head of the reserve police, assigned three policemen to carry out the arrests: Shkoliar, Rozum and Karabylo (or Karabylov, according to the statements of Kupriianenko). On his orders, they arrested up to 10-15 persons who were subsequently shot.28

Thus, members of the local police were involved in the crimes of the Germans on the territory of Kryvyi Rih to various extents. The available criminal files make it possible to identify individuals who participated in the Holocaust in Kryvyi Rih and surroundings. However, this overview is far from complete, so research into the Jewish genocide in the city and surroundings is not a closed chapter.

More is known about the role of members of the auxiliary police in the “action” of 14 October 1941. The aforementioned policeman Sobko gave the most comprehensive testimony about the course of the action of 14 October. His statements have been made public and analyzed in previous examinations of this topic.29 In particular, he stresses that the police started gathering the Jews in the synagogue already on the eve of the shooting. At 10 A.M. on 14 October, the Jews were led to the shooting site. Ahead of the shooting, Oleksii Pasternak and Mykhailo Strykal’ entered the synagogue carrying suitcases. They took away from the Jews their wrist and pocket watches, their gold and silver jewelry, and other things. All these items were delivered to the head of the local police, Taranenko, and the office of his deputy, Vasyl’ Pasternak.30

During the convoying to the shooting site, Sobko, according to the testimony of witness Anna Atanashchenko, beat up a Jewish woman who was lagging behind.31 During the shooting itself, the policemen assisted the Germans. They singled out groups of ten persons, who they undressed and led to the shooting site. After the shooting, they collected the items and valuables that had not been confiscated in the synagogue that morning.32 Noteworthy is Sobko’s statement that three people stayed alive because their parents turned out to be Russian.33 However, further details about these three and their fate could not be established.

Moreover, the shooting of civilians was followed by the shooting of POWs of Jewish ethnicity. Sobko stated that no less than 300 POWs were shot.34 The actual figure was probably closer to 800. Whether these POWs were all of Jewish origin, is difficult to say, since it is certain that there were also communists and military commanders among them.

After the shooting, all possessions of the victims were brought to the premises of the aeroclub, from where they were transported to the police storage using eight carts. Ivan Kalashnykov, the manager of the police storage at that time, was in charge of this operation. Subsequently, the clothes were handed out to civilians, employees of the occupation administration, and policemen. Kalashnykov also kept items for himself: four pairs of men’s underwear, three shirts, four towels, one pair of shoes, two dresses, two pairs of breeches.35

Thus the statements by the policemen and witnesses have made it possible to identify the individuals involved and to reveal details about their crime, in particular the robbing of the Jews prior to the shooting, the beating up of a Jewish woman during the convoying, the role played by local policemen, and lastly the economic component of the events of October 1941.

Identifying the murdered Jews

It is no less important to identify the victims of the Holocaust in Kryvyi Rih and surroundings. It has so far proven impossible to establish all the names of Jews who were killed during the occupation of Kryvyi Rih. However, the statements of the policemen sometimes feature names of persons of Jewish ethnicity who were killed. Local policeman Ivan Zhyl’tsov testified that in January 1942, he arrested his Jewish neighbor, Iakov Suponyts’kyi, who had been hiding behind a secret wall in his house for a long time. He lived in house No. 32 in the Pushkin Cul-de-sac. After his arrest, Suponyts’kyi was shot, and Zhyl’tsov seized some of the victim’s property for himself.36 T. Khitrenko, a witness in Il’chuk’s case, testified during a confrontation with Il’chuk that in November 1941, a man named Serhii Moskvyn was arrested after Il’chuk forced him to confess his wife was Jewish. Moskvyn was beaten up and sent to detention. His wife, M. Vinar-Moskvyna, was arrested together with their two children and murdered shortly after together with her infant child, while their two-year-old was returned to Moskvyn.37

However, mentioning the names of Jews was the exception rather than the rule. Most statements by the policemen contain only general information about citizens of Jewish ethnicity. Their personal details are, as a rule, not discussed. Occasionally, information about their sex, age and place of residence is provided. For example, policeman Petro Hladchenko testified during an interrogation that at the end of the winter of 1943, he had arrested a Jewish boy who looked 14-15 years old and was, at the time of arrest, living with a resident of the Kirov mining settlement called Kateryna.38 Another example can be found in the case against Ivan Kalashnykov. He testified that in the autumn of 1941, he, together with policeman Hryhorii Suprun, drove out to the settlement of Zmychka to arrest a local Jewish resident. They arrested her together with her two children and delivered her to a police office.39 Apart from her sex, address and family situation, Kalashnykov’s statements do not reveal anything about the identity of this individual.

In other cases, the identification of individuals of Jewish ethnicity made it possible for the accused to reduce the severity of the charges raised against them. Thus, local policeman H. Pliako stated that he, in the summer of 1943, helped a forty-year-old Jewish woman named Mariia Shneider get released. Shneider lived in the Zhovten’ mining settlement.40 In the investigation file, her name is mentioned only once in the statements of the accused. The investigators either couldn’t find her or didn’t bother to look for her to bear witness. Another, similar episode can be found in the file of policeman Semen Petrychenko. He claimed to have been arrested by the Germans because four Jews had been discovered to be hiding in his building. Petrychenko knew them from before the war. Noteworthy is that he called them by their surnames: Krasnopol’s’kyi and his daughter, Bronshtein, patronym Davydovych, and Samuïl Tovarovs’kyi. They were all arrested and shot shortly after. Petrychenko himself was released from custody one month later, since he was able to prove during the investigation that these persons had visited him only a couple of times, and that he had been unaware of the fact they were staying in his building.41

Thus, the interrogation records of the policemen reveal important details about the victims of the Holocaust. But it should be added that the policemen involved were guided first and foremostly by the desire to avoid severe punishment, and this motive has to be taken into account when analyzing these sources.

Studying other crimes against the Jews

The interrogation records are also an important source for revealing other criminal activities of the local policemen concerning the Jewish population of Kryvyi Rih and surroundings. For the entire duration of the occupation, the search for and extermination of Jews was one of the prime tasks of the local police force. That is why the interrogation records very often contain information about arrests of Jews, their deployment for various kinds of forced labor, and, ultimately, their elimination.

A report by major Regler, the head of the German field commandant’s office, has revealed that during the first weeks of the German occupation of Kryvyi Rih, the possibility of creating a ghetto in the city was under consideration.42 This explains why local Jewish residents were actively deployed for various kinds of forced labor during this period. For instance, the statements of policeman Ivan Semka reveal that in September 1941, he, together with other policemen, was responsible for convoying Jews living on Karl Liebknecht St. and Saksahans’kyi St. to labor sites.43 A similar episode can be found in the statements of I. Kalashnykov. During his investigation, he testified that he had been in charge of four individuals of Jewish ethnicity who worked at the police station, cleaning the premises and storage. They continued living in their own houses and came over to the prison yard every morning. For about a month they continued working in this way, until they did not show up for work one day – their fate is unknown.44

After the mass shooting on 14 October 1941, there were almost no Jews left in the city. Nonetheless, the police continued to track down individuals of Jewish ethnicity, who were arrested and, in most cases, shot.

According to statements by policeman Henadii Beloshystov, in the winter of 1942, groups of predominantly Jewish detainees were held captive in the cellar of the Kryvyi Rih SD. In January 1942, for instance, nearly 60 arrested Jews were being held there. And in February 1942, the cellar was populated by children, women and elderly of Jewish ethnicity. Their daily ration was 50 grams of bread, and sometimes nothing at all. When they were led outside for yard time, a woman turned to Beloshystov begging him for some bread. Beloshystov gave her a loaf of bread, after which Kalashnykov told him: “Why do you feed them, they will be shot anyway.” A few days later, the group was indeed shot.45

Thus, the interrogation records of policemen and witnesses are the most informative of all materials in the criminal files with regard to the Holocaust in the city. They make it possible to establish concrete details about the murder of the Jews, to identify the locals who were involved in murdering them, and to assess, to some extent, the public opinion of the city’s non-Jewish inhabitants with regard to the Jewish genocide. However, these sources need to be studied in combination with other criminal files, as well as with other materials (such as diaries, letters, etc.) contained in the appendices to the cases themselves.

Trial documentation

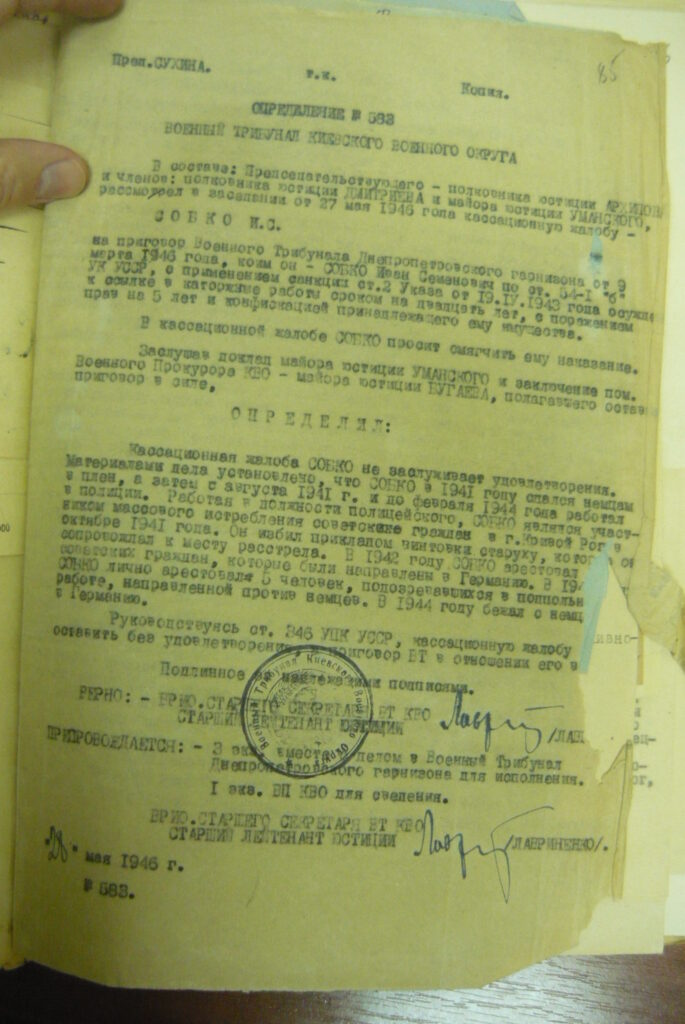

The final body of materials in the investigation files is the trial documentation. More specifically, these are the record of filing investigative materials, the indictment, and the verdict of the court (or extrajudicial organ, tribunal, etc.). These documents may also contain information about the Holocaust, but with a difference: if the arrest warrant treated the crimes against Jewish individuals as mere suspicions, the indictment and, especially, the verdict present these crimes as faits accomplis. Thus, the indictment of policeman Sobko states that he was involved in convoying Jews to the shooting site in October 1941 and in beating up a Jewish woman during this event.46 However, in a typical second difference, the fact that he was responsible for beating up an elderly Jewish man in September 1941 is left unmentioned. Instead, he was accused of conducting anti-Soviet agitation among the local population during his service in the police. And this accusation was substantiated by reference to the witness statements of M. Man’ko and Ie. Kostenko, who also testified about the aforementioned beating of an elderly man in a bread line. I presume his latter accusation was dropped due to the tradition in judicial practice of “burying” “lighter” crimes under “heavier” ones in complex cases. And for the Soviet judicial system, anti-Soviet activities carried more weight than violence against an elderly Jew. Therefore the investigators decided to emphasize the anti-Soviet activities.

The indictments of policemen who were arrested in the 1950s were drafted with more care. In the file of A. Il’chuk, the indictment comprises eight pages. It presents in detail his criminal activities with regard torepresentatives of the Jewish ethnicity, and outlines the evidence more thoroughly. Il’chuk was accused of convoying Jews to the shooting site in October 1941 and giving the order to collect their valuables. After the mass shooting at mine No. 5, he used a list received from policeman Bozhko to order the arrest of at least 15 Jews, among whom were Rodynovs’kyi and Moskvyna-Vynar. He also pushed Ivan Kholiavlo to admit his wife Khana was Jewish, after which both were forced to flee and go into hiding.47

Thus, indictments may also contain information about the Jewish genocide in the city. But in contrast to interrogation records or arrest warrants, these documents, in principle, must contain proven facts, which serve to objectively determine the degree of culpability of the accused. Trial documentation from the first postwar years differs from similar documentation issued in the 1950s. The latter tends to be of higher quality and to be grounded in thorough evidence.

Conclusion

In sum, the criminal files of Kryvyi Rih policemen from the SBU archive hold enormous potential for research on the Holocaust in Kryvyi Rih and surroundings. The largest body of information about the Catastrophe is concentrated in the arrest warrants, interrogation records, and the indictments and verdicts. Together, these materials make it possible to study the course of events during the largest mass shooting of Jews in the city on 14 October 1941, as well as to identify the perpetrators and victims of the Holocaust in the region. The materials in question also allow for research into other criminal activities of the local policemen with regard to the Jewish population. Nonetheless, work on the criminal files of the Kryvyi Rih policemen is ongoing, and many aspects of the Holocaust in Kryvyi Rih and surrounding have yet to be researched. In particular, materials concerning the mass action to exterminate Jews near the settlement of Inhulets’ remains understudied, as well as similar actions in the northern part of today’s Kryvyi Rih, especially in the settlement of Veseli Terny. These episodes require for more criminal files of local policemen to be processed and analyzed.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Tobias Wals

This research was made possible by the Solidarity Fellowship, sponsored by the Institute for Human Sciences (Vienna)

- Also known as the SBU Archive or, colloquially, the KGB Archive (note by the translator). ↩

- I. Dereiko, “Arkhivno-slidchi spravy iak dzherel’na baza doslidzhennia osobystoho vymiru proiaviv zbroinoho kolaboratsionizmu v Reikhskomisariati ‘Ukraïna’”, Storinki voiennoï istoriï Ukraïny, No. 13 (Kyiv: Institute of History of Ukraine at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 2010), 35. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17980, ark. 3. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17233, t. 1, ark. 2. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 18955, ark. 2. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17911, ark. 3. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 15055, ark.3. ↩

- The Ukrainian word natsional’nist’ is translated as ethnicity rather than nationality, because the latter term is usually associated with citizenship of a particular state (note by the translator). ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17277, ark. 2. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 14293, ark. 3. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 18835, t. 1, ark. 5. ↩

- Idem, ark. 6. ↩

- Idem, ark. 254, 266. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 11857, t. 1, ark. 9. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 18955. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 11857, t. 1, t. 2. ↩

- T. Penter, “Pid slidstvom za spivpratsiu: sudove peresliduvannia kolaborantiv u SRSR pislia Druhoï svitovoï viiny ta zlochyniv u Babynomu Iaru”, Babyn Iar: masove ubystvo i pam’iat’ pro n’oho: Materialy mizhnarodnoï naukovoï konferentsiï, 24-25 October 2011, Kyiv (Kyiv: Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies, 2012), 193-194. ↩

- Idem, 195. ↩

- A. Kruglov Bez zhalosti i somneniia. Dokumenty o prestupleniiakh operativnykh grupp i komand politsii bezopasnosti na vremenno okkupirovannoi territorii SSSR v 1941-1944 godakh (Dnipropetrovsk: Tkuma, 2008), part III, 206-2011. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17233, t. 1, ark. 26. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 18955, ark. 46zv.-47. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 11857 , t. 1, ark. 45-45zv. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 75, t. 4, ark. 86. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17277, ark. 22. ↩

- Idem, ark. 23. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 16681, ark. 73. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 14293, ark. 46-48. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 18835, t. 1, ark. 95-99. ↩

- R. Shliakhtych, “Uchast’ mistsevoy dopomizhnoy politsiy u Holokosti na Kryvorizhzhi (1941-1942 rr.)”, Holokost i suchasnist’ 1 (14) 2015, 75-88; R. Shliakhtych, “Holokost na Kryvorizhzhi: vykonavtsi ta zhertvy”, Muzeinyi prostir: zberezhennia ta prezentatsiia predmetiv iudaïky: Materialy Vseukraïns’koho naukovo-praktychnoho seminaru (18-20 October 2017) (Kryvyi Rih: R.A. Kozlov, 2017), 82-93. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17911, ark. 53. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17277, ark. 36. ↩

- Idem, ark. 23. ↩

- Idem, ark. 24. ↩

- Idem, ark. 25. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 14293, ark. 28. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17233, ark. 179. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 18835, t. 1 , ark. 249. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 15862, ark. 141. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 14293, ark. 27-27zv. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 15862 , ark. 53. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 15055, ark. 32-33. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 75, t. 4, ark. 71. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17233, ark. 152. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 14293, ark. 32. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 14293, ark. 46-48. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 17277, ark. 65. ↩

- DA SBU, Dnipro, f 6(R), op. 2, spr. 18835, ark. 217-218. ↩