This series of the EHRI Document Blog gives space to the discussion of current spatial projects and analyses focusing on different aspects of the history of the Holocaust. Inspired by the methodologies of the spatial studies, researchers focus on place and space, proximity and distance, movement or the decision to stay, not only by mapping a physical geography, but also by examining how space is constructed, processed and perceived. Looking at the Holocaust through space makes it possible to change scales and to better integrate local collections, data, and knowledge into the transnational perspective. In keeping with this thriving aspect of spatial studies on the Holocaust, the EHRI Document Blog series Holocaust Geographies is an arena for posts showing how thinking through space and place and experimenting with their visualization provides a framework for exploring new views on the Holocaust.

‘Place is not only a fact to be explained in the broader frame of space, but it is also a reality to be clarified and understood from the perspectives of the people who have given it meaning.’1

Introduction

The Wiener Holocaust Library is the UK’s largest archive of personal papers related to Jewish refugees from Nazi Europe. We hold over 700 family papers collections, most of which are related to the experiences of Jewish refugee families who came to Britain in the 1930s and 1940s. The collection includes an incredible amount of original materials, including diaries, Red Cross letters, photo albums, identity and emigration papers, and recorded interviews. We are still actively building our collection of family papers, and our ever-busy Senior Archivist typically accepts around fifty donations per year by word-of-mouth alone. Additionally, the Library holds copies of 250 interviews with Holocaust survivors and refugees speaking about their experiences in Nazi-occupied Europe and transitions to life in Britain through the AJR Refugee Voices audio-visual archive, among other testimony collections such as the Yale Fortunoff and USC Shoah Foundation collections. Despite the importance of these unique holdings, however, our refugee family papers are often overlooked by visitors to our Reading Room. Last year, for instance, only around forty family papers collections were consulted at the Library.

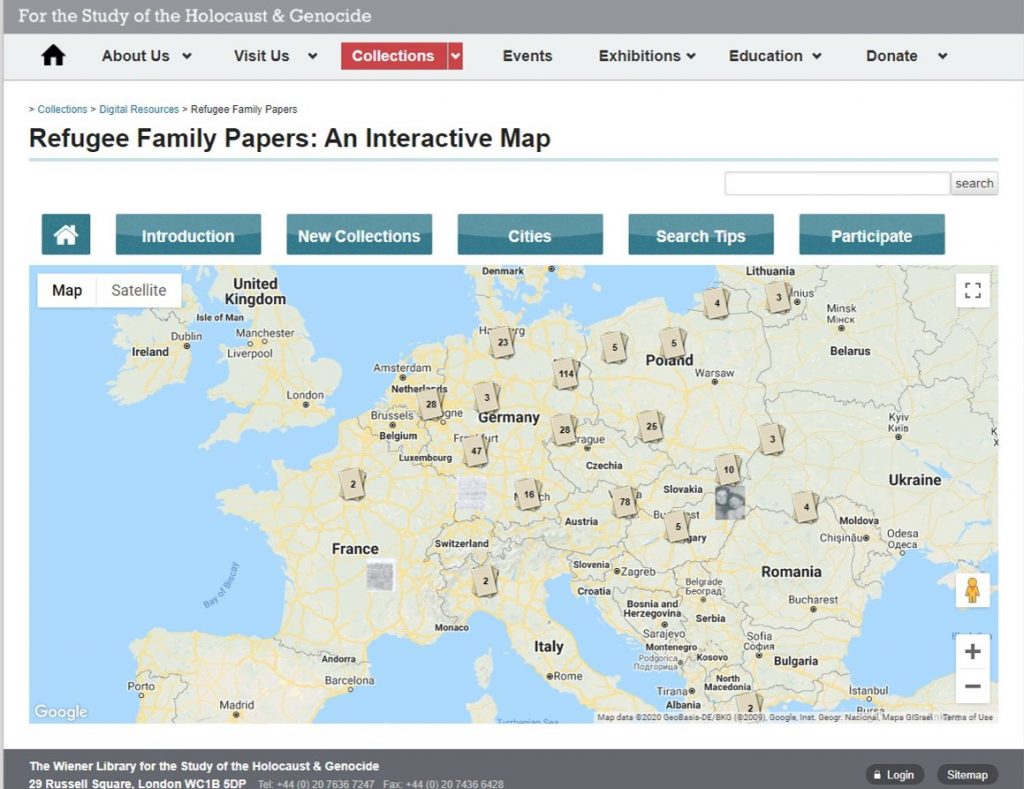

In 2015, the Library created a basic visual reference for our collection of Family Papers, which was accessible as a page on our main website. The Refugee Family Papers: An Interactive Map was our first online resource featuring digitised collections. The original page represented each collection as a single pin on a map, with a location related to the family’s ancestral home or their last address before they fled the country. Most of the pins, reflecting the biases of our collection, were concentrated in Vienna, Berlin and other urban centres in Germany. Due to this, the amount of information linked to each bit was often inconsistent; while there was some material linked to location, a single pin often included images or audio related to other places, times, extended family members and friends. Unedited biographical histories from the catalogue summary served as the description for each collection.

Site analytics and a user survey revealed a lack of engagement with the Interactive Map, both in terms of overall visitor numbers and how users interacted with the site. Across a four-year period, the site had only accrued around 3,000 page views in total, with users only spending a couple minutes on the site. The lack of a clear narrative and consistency between the types and amounts of information about each collection seemed to frustrate users, and the old site proved difficult to search, with few helpful keywords. Those surveyed who had used the site tended to be depositors of one of the collections represented. Donors would use the resource to share their family history with friends and relatives. Others wanted to look at collections related to areas linked to their own family history. While the old site served as an important digital memorial, the collections, by and large, were not being accessed by a more general audience or for educational purposes.

In 2021, a grant from Arts Council England gave the Library the chance to enhance and re-think this resource, in order to make it considerably more accessible, engaging and appealing for new and existing audiences. The digitisation and publishing of select materials online also allows us to provide greater access to the collections among people unable to travel to London to visit the Library.

Adapting the archive

Ahead of designing a new site, several core aspects of the existing map and the presentation of our documents were challenged:

- Why ‘refugee’ and not another term? The use of words like ‘displaced’ or ‘displacement’, for instance, would also encompass instances of forced intra-state movement.

- Given the majority of our document collections involve upper and middle-class Jewish refugee families who settled in the UK from Germany or Austria, did it make sense to equally keep the scope explicitly tailored towards our archival strengths? Or, should the map aim to be more overtly curated, offering a greater range of experiences as a general, educational resource about refugees of the Second World War or an even greater scope?

- Does the use of a map format flatten and simplify the subjects of our collections, portraying their often quite complex, confusing and incomplete stories to a reductive narrative?

- Who is the audience for this resource, and what is its purpose?

A wealth of scholarship exists around these tricky debates; the question of ‘mapping’ the Holocaust or survivors’ experiences has had many sensitive and innovative responses to visualise movement, experience, and memory.2 Additionally, contemporary discourse on the representation of ‘refugees’ in media and development studies has often centred on the concept of dignity, individualism versus collectivism, and the relationship between viewer and viewed. For the answers to these questions, however, we often returned to this final point: who and what is this map for? As a public archive with an educational mission, the Library’s Refugee Map was ultimately a way to open up our collections. For instance, as this resource sought to target a general audience, the term ‘refugee’ is more instantly recognisable and commonly understood. Furthermore, using a simple title which is broad enough to encompass any further expansion helps with long-term sustainability. The resource openly reflects our collections, with all their limitations and strengths, and we concluded it would have been misleading to present it as a comprehensive or ‘proportionate’ range of perspectives, locations, or backgrounds. The Library’s Refugee Map remains an invaluable visual extension of our archival holdings.

While developing this resource, I looked at practical examples of both mapping collections and strategies for telling archival, Jewish, and refugee stories online. These included larger and participatory undertakings such as Layers of London, more curated and scholarly collaborative projects such as A Memory Map of the Jewish East End, and interview-related maps in the overview approach of AJR Refugees Voices and the personal testimony mapping in USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. Contemporary refugee projects also offer fascinating approaches, varying from the more conventional to the rather experimental. The Refugee Project shows abstract flows of mass migration throughout time; Migration Trail uses a real-time collage of fictional data visualisations to provide a theatrical, immersive experience of an individual refugee’s story through text messages, social media posts, and audio. A significant portion of contemporary refugee mapping projects focuses on individuals—like Placing Oral Histories, for instance. Similar strategies have been used by NGOs in their photography and materials.

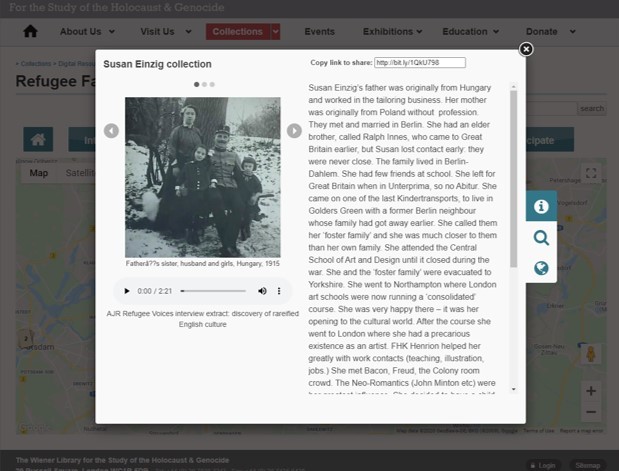

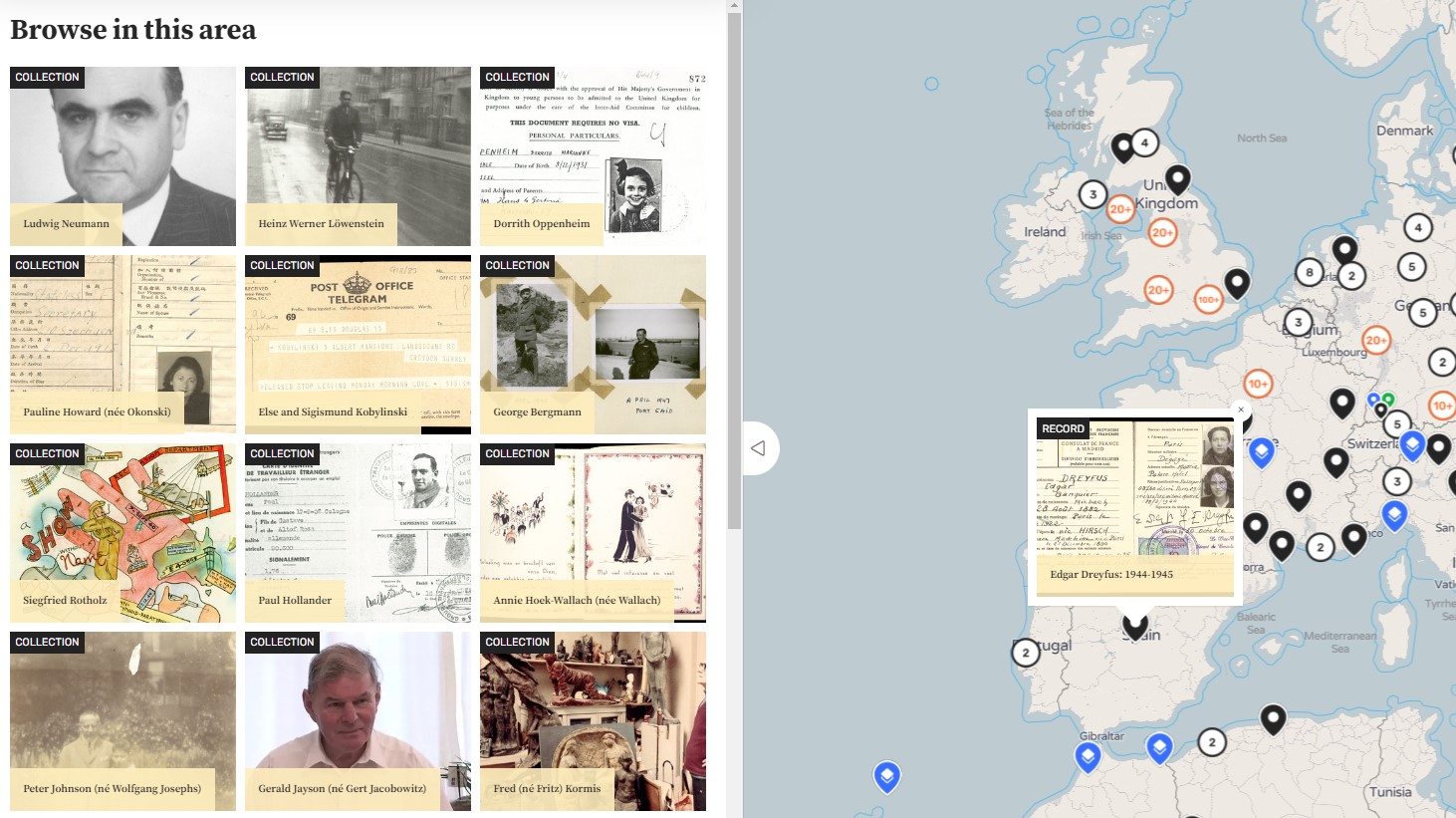

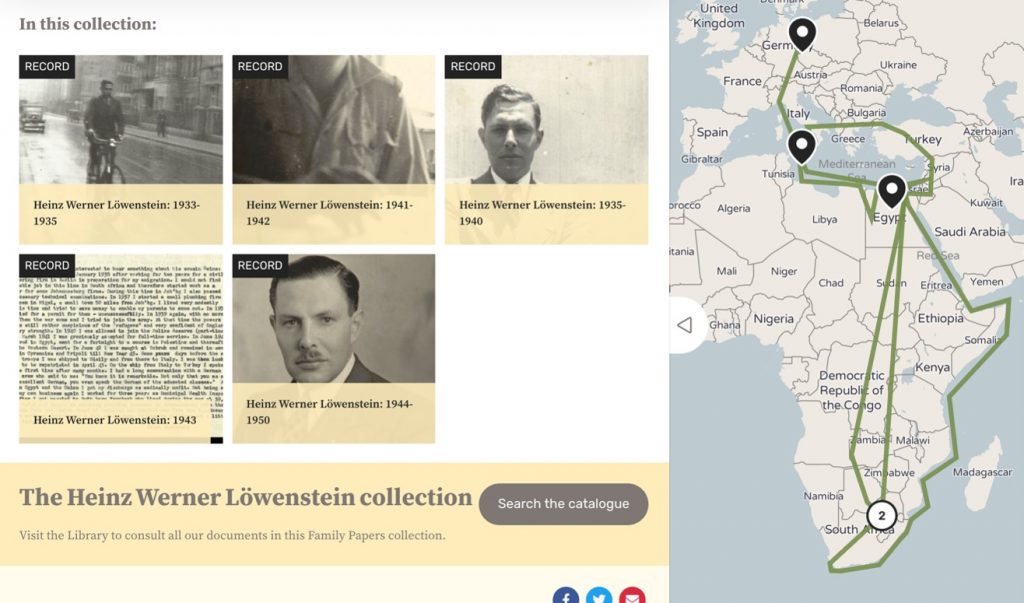

The Library’s Refugee Map, designed together with Humap, centres on personal, micro-histories of the Holocaust and the Second World War while using cartographical tools to visualise temporal and spatial movement. Humap is a continuously updated platform that specialises in telling stories with interactive maps, focussed on providing an intuitive user experience. Working with the Humap team, we anchored the core building blocks of the site (Collections and Records) on individual and family’s experiences — both in content and visually — to provide a human face to cartography, a medium forever at risk of dehumanising the communities it represents through data reduction and abstraction. While the old map collapsed multiple stories into a single location, our new version uses multiple Records to clearly situate time and place and to help clarify where different archival documents fit within often-complex journeys. Each Record includes different types of materials—video or audio clips, photographs, documents, and multi-page memoirs—mixed within one, cohesive gallery. Quite a number of our collections include materials from the late 19th-century, and the shifting borders of countries (such as the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Prussia) often impact the cultural identities of the families in our collection; the inclusion of a number of Overlays in the form of historic maps provides a useful reference. Routes provide more of a visual tool show the approximate journey across the map for a refugee family or family member, linking together different pins on to show, if known, the general path of the journey (where they left or entered a country).

The Refugee Map also enables different searching options: moving the map itself and clicking on pins, using the Browse feature while moving the map, typing in terms or selecting different media in Search (all text in the Record and Collection is searchable), clicking on themed groups, and using keyword tags. These keywords include the type of media, time period, location, organisation, and shared or common experiences—similar to AJR Refugee Voices’ own useful, thematic groupings. Each Collection also includes a link to the related collection held at the Library, prompting further consultation with our archive.

Archival storytelling

In practice, different types of material in the collection play different roles towards telling these families’ stories towards a general audience, especially within a biographical format that emphasises order, chronology, and individual perspectives.

The first loose group of materials are memoirs, captioned photos or photo albums, and written or audio interviews with former refugees and their relatives. These are quite directly in their own voices and with often the explicit intention to preserve their history for future generations or a public audience.

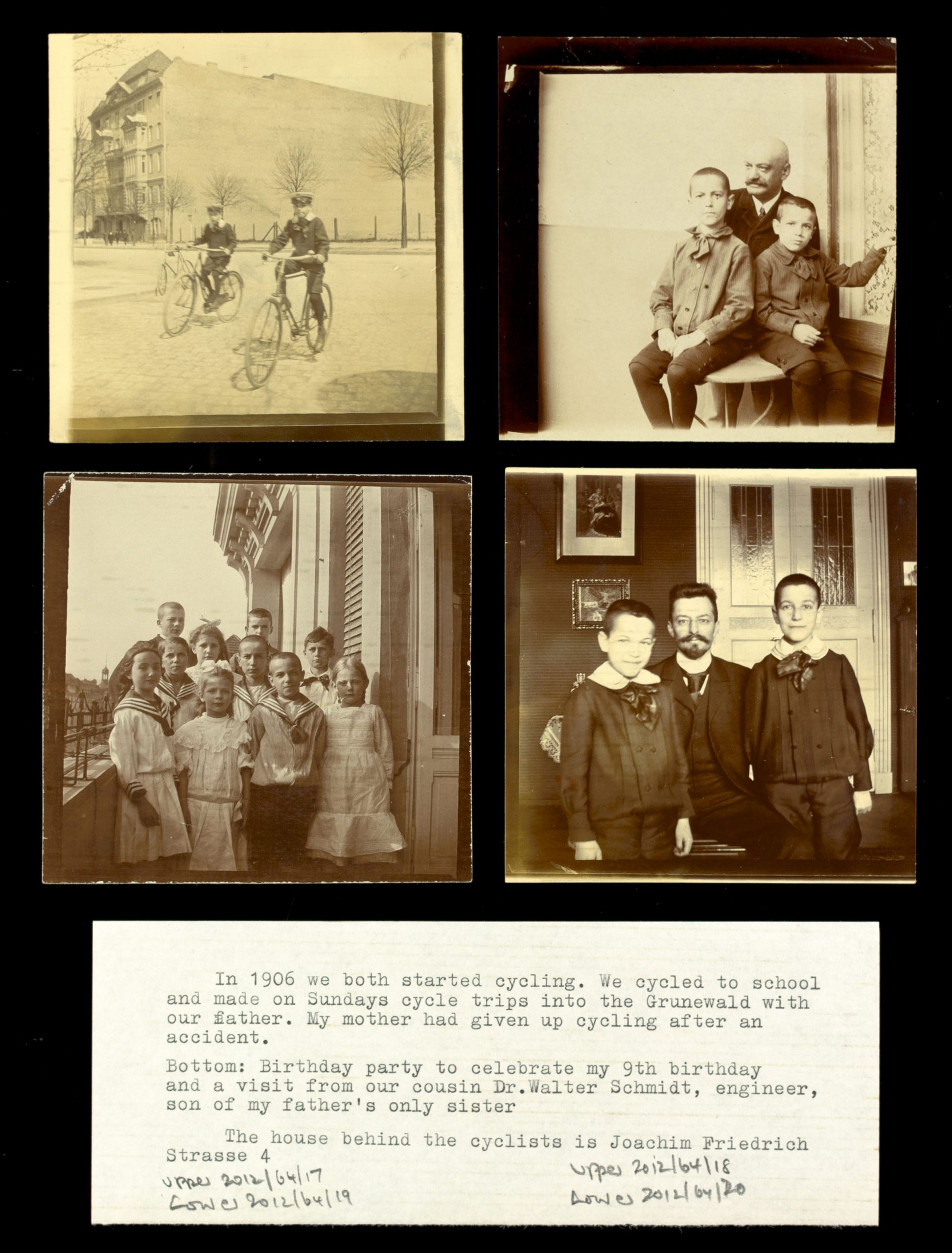

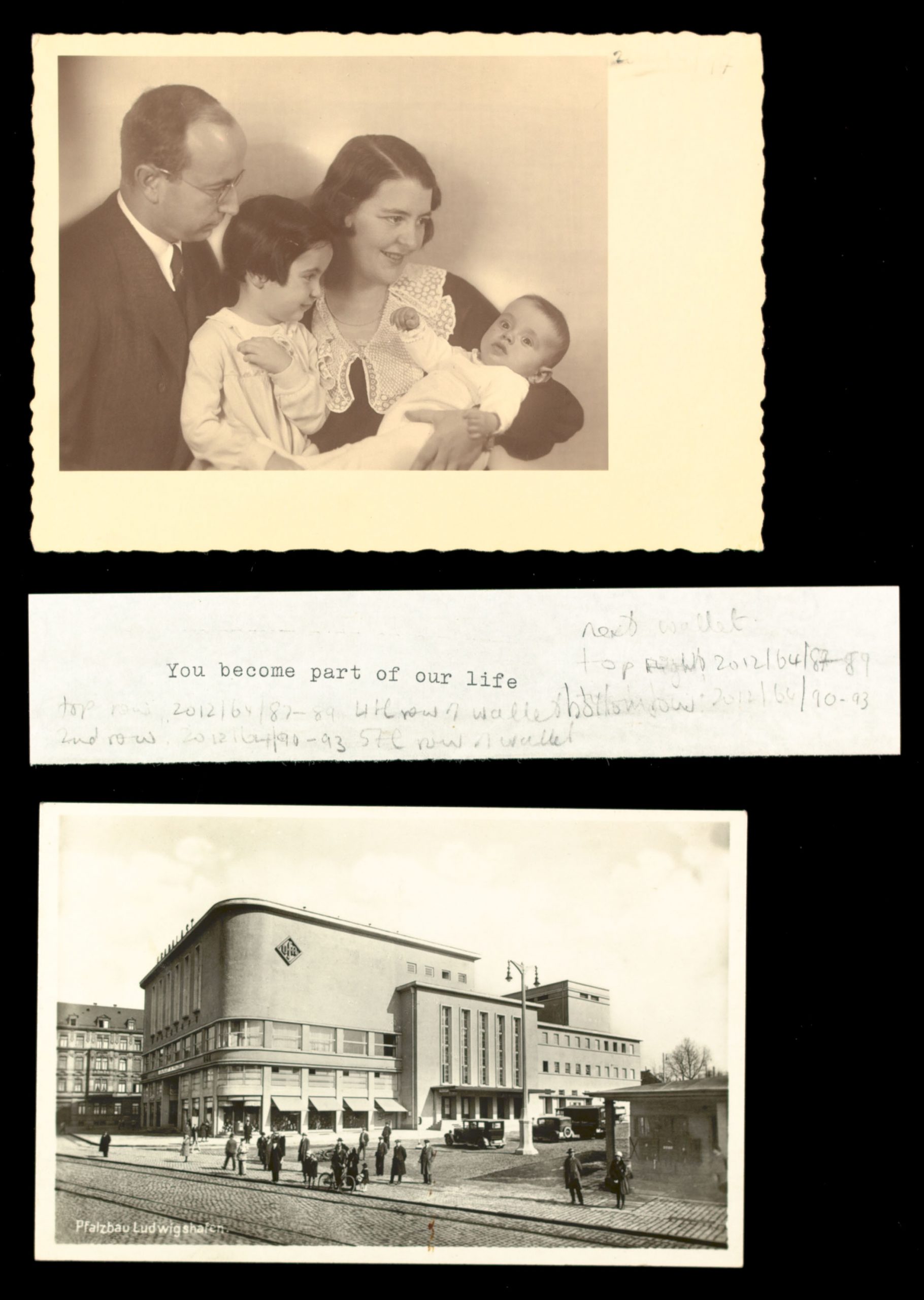

One of my favourite objects in the collection is an annotated album by Louis Linton (né Ludwig Liebermann) created for his children, Eva and Albert. It demonstrates how engaging this type of material is for creating an emotional connection between our collections and an audience. Each page includes personal captions that bring the photographs to life.

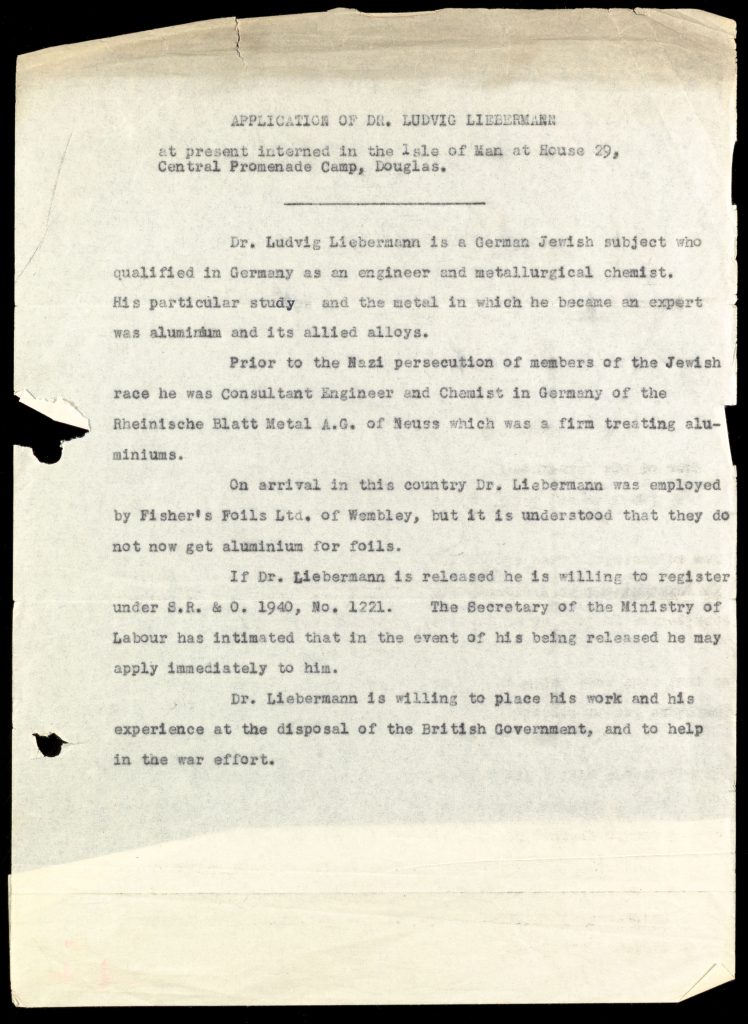

The album seems to take us through Louis’s life, including childhood snapshots from early 1900s Berlin, portraits in military uniform during the First World War to holidays abroad in Europe in the 1920s and meeting his future wife, Susan Maria Linton (née Susanne Marie Friedmann). The birth of his children is marked with a very tender caption; a selection of pictures seems to document his life in the UK from the late 1930s and the 1960s. It is also notable, however, that other documents in the collection paint a less rosy picture of his time in the UK, with a number of contemporaneous letters and documents highlighting precarity, indignity and trauma through internment as well as the loss of friends, family and livelihood.

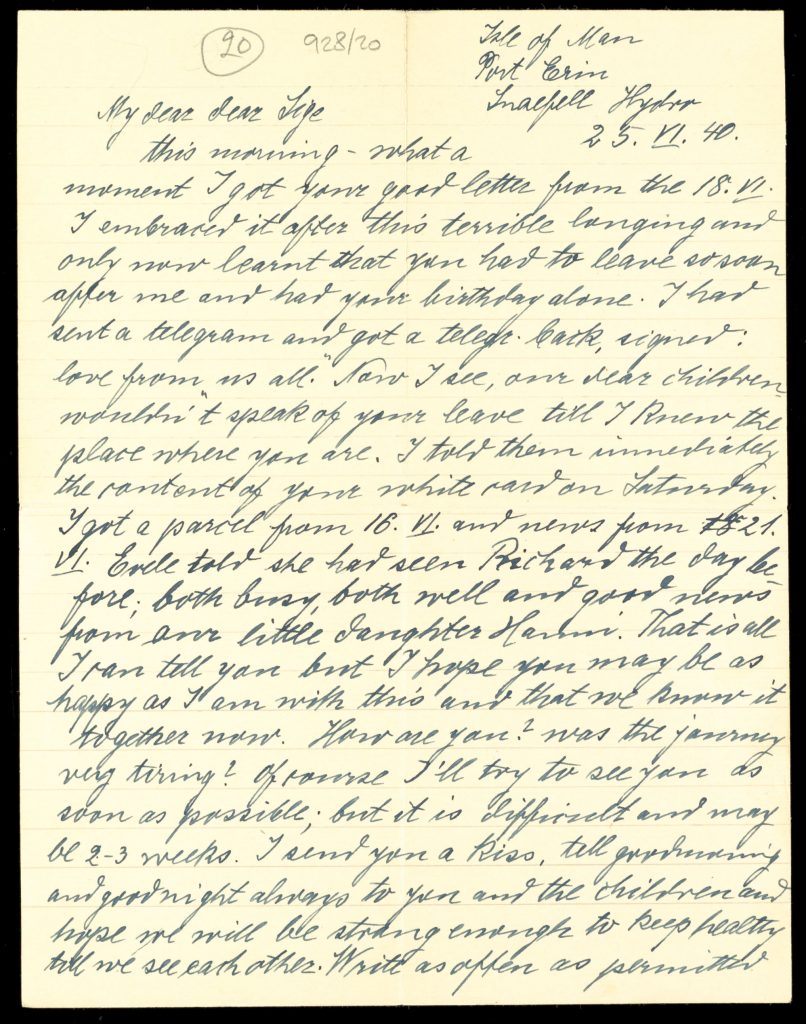

The second general group of materials on the Refugee Map are contemporaneous correspondence in the form of personal letters. These letters are not written expressly for a future audience, but provide vivid details about what the families might be experiencing. They also develop a personal view, often providing a family member or friend’s commentary of their everyday experiences as refugees.

Often, it is interesting to read not only what is written about but also what is left out—or even how something is written. This letter from Else Kobylinski to her husband Sigismund was written during their internment on the Isle of Man in 1940 in separate camps—both suffered very poor health while interned. Here, she writes in English as a way of getting through the censors more quickly.

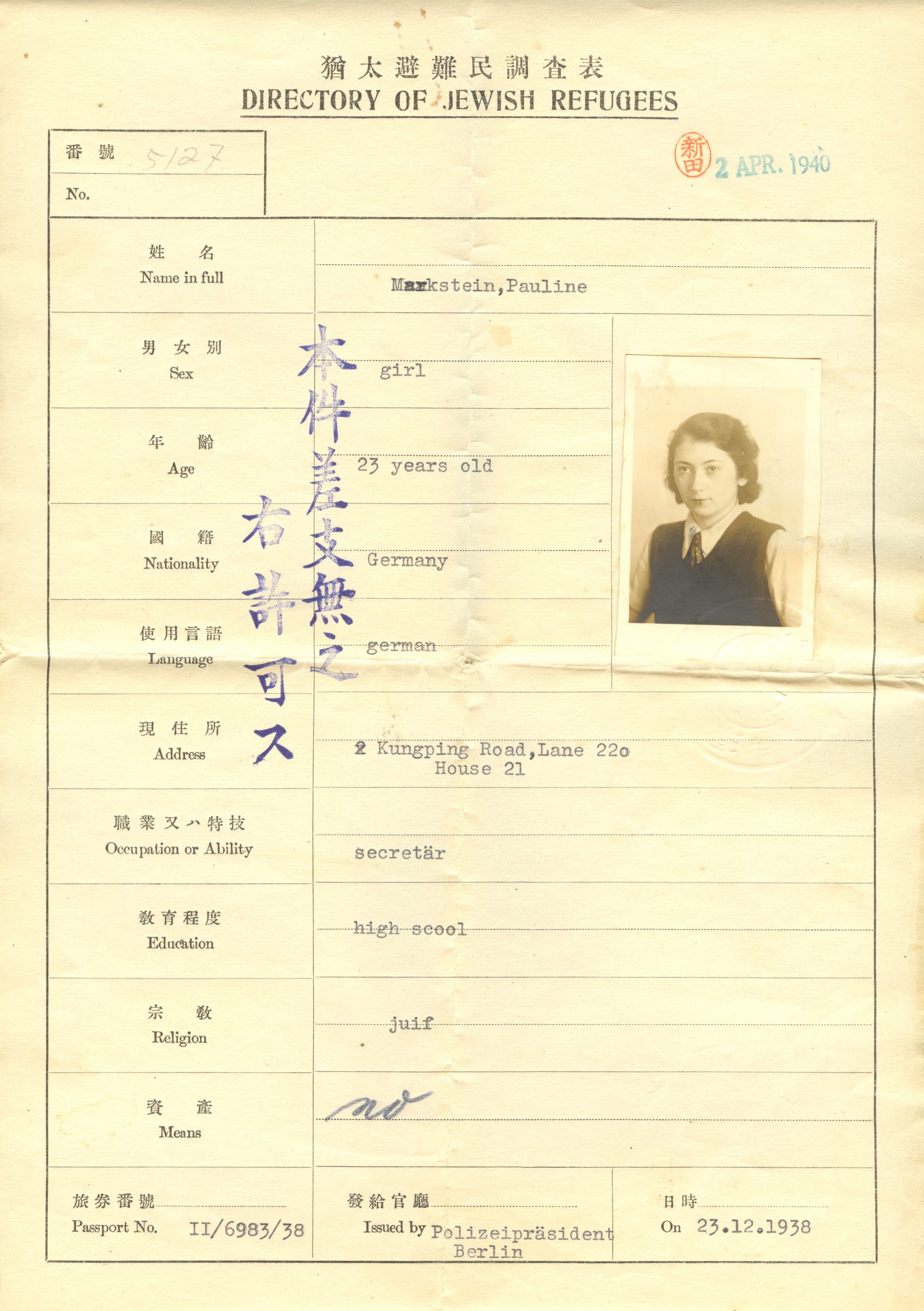

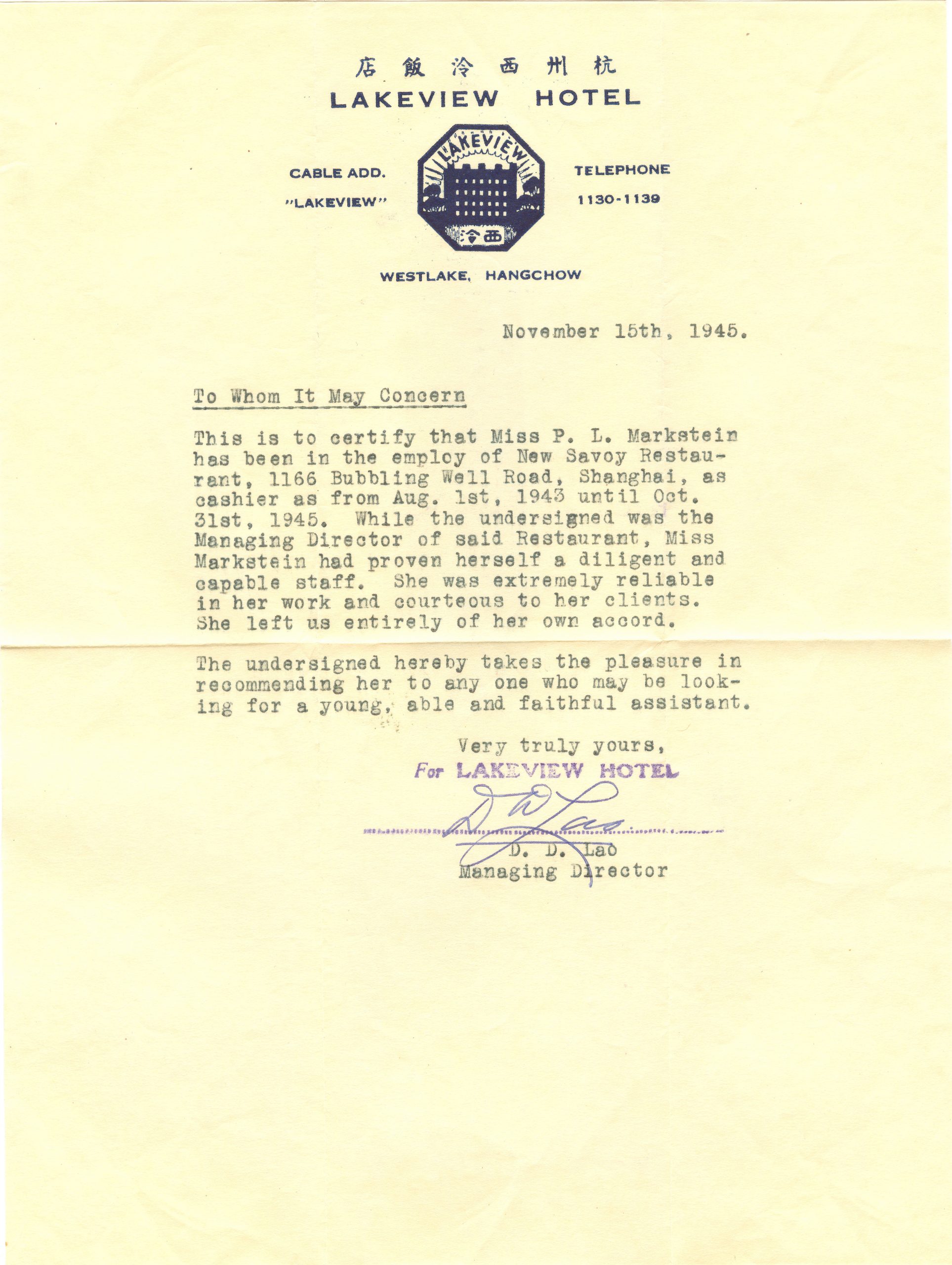

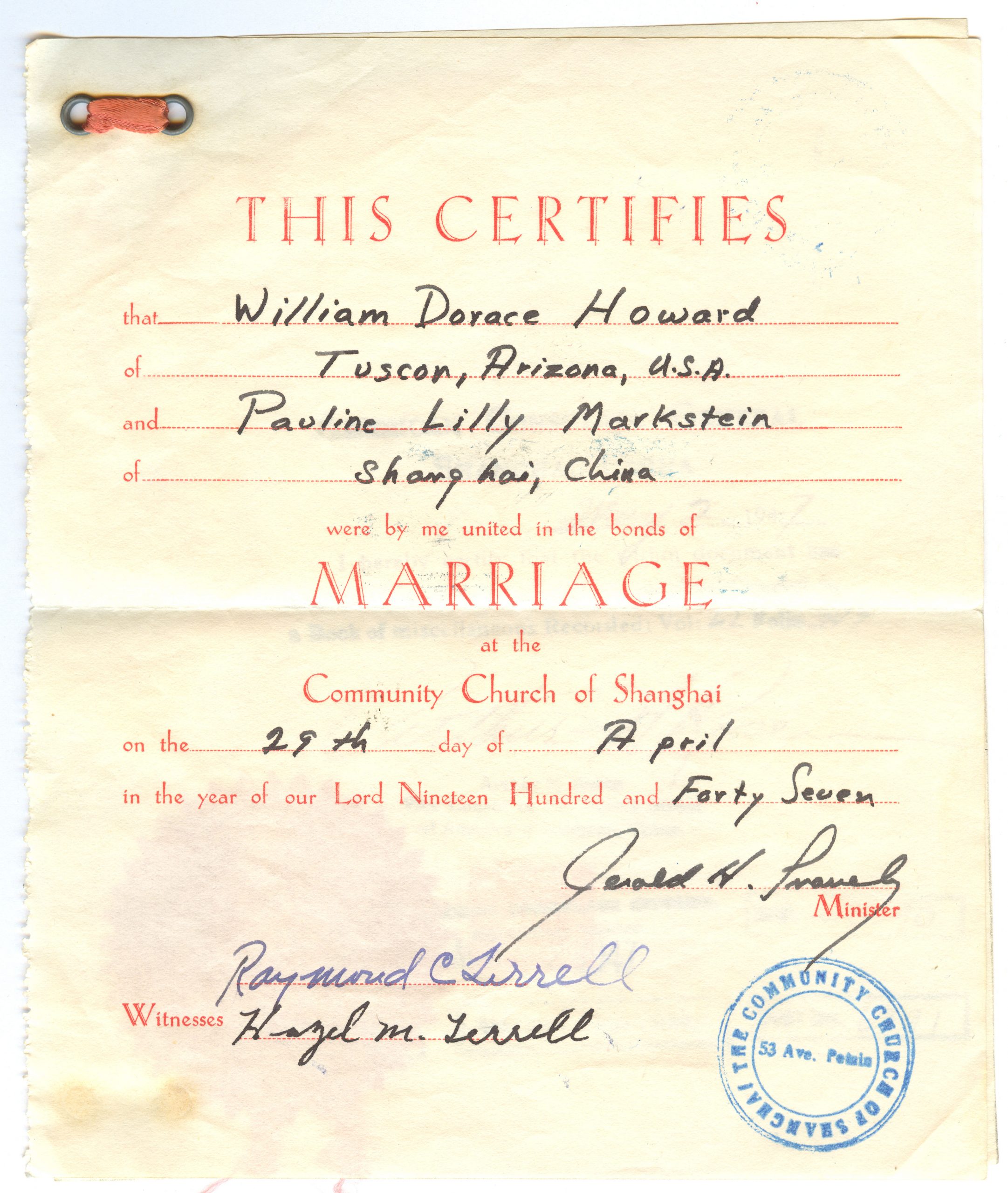

A third group of materials are travel and administrative personal documents which can indirectly show what the individuals or family members might have experienced, where they went, and when key events happened in their lives. This includes materials like identity cards, passport stamps, birth and naturalisation certificates, wedding and divorce decrees, restitution forms, job references, shipping lists and ticket stubs. In essence, many of the same types of important documents most people would preserve today.

In the case of the Pauline Howard (née Okonski) collection, all the documents consist of this type of materials. While lacking Howard’s direct voice, a clear outline between time and place seems to solidify. A Jewish refugee registration card issued in Shanghai includes a photo of Pauline Markstein in her early 20s with information on her education and previous work as a secretary in Berlin. A general job reference letter demonstrates that she worked for a few years as the Managing Director of a restaurant in Shanghai. A 1944 divorce decree from her first husband Herbert Markstein, also a Jewish refugee from Germany, is followed by a 1947 marriage certificate with William Howard, a lieutenant in the US Navy. The collection’s folder seems to end with a passenger identification for arrival to the US from California. While a clear timeline seems to emerge, there is no deeper information on what Pauline Howard experienced or felt. The gaps and silence in this collection are particularly striking within the Refugee Map’s structure.

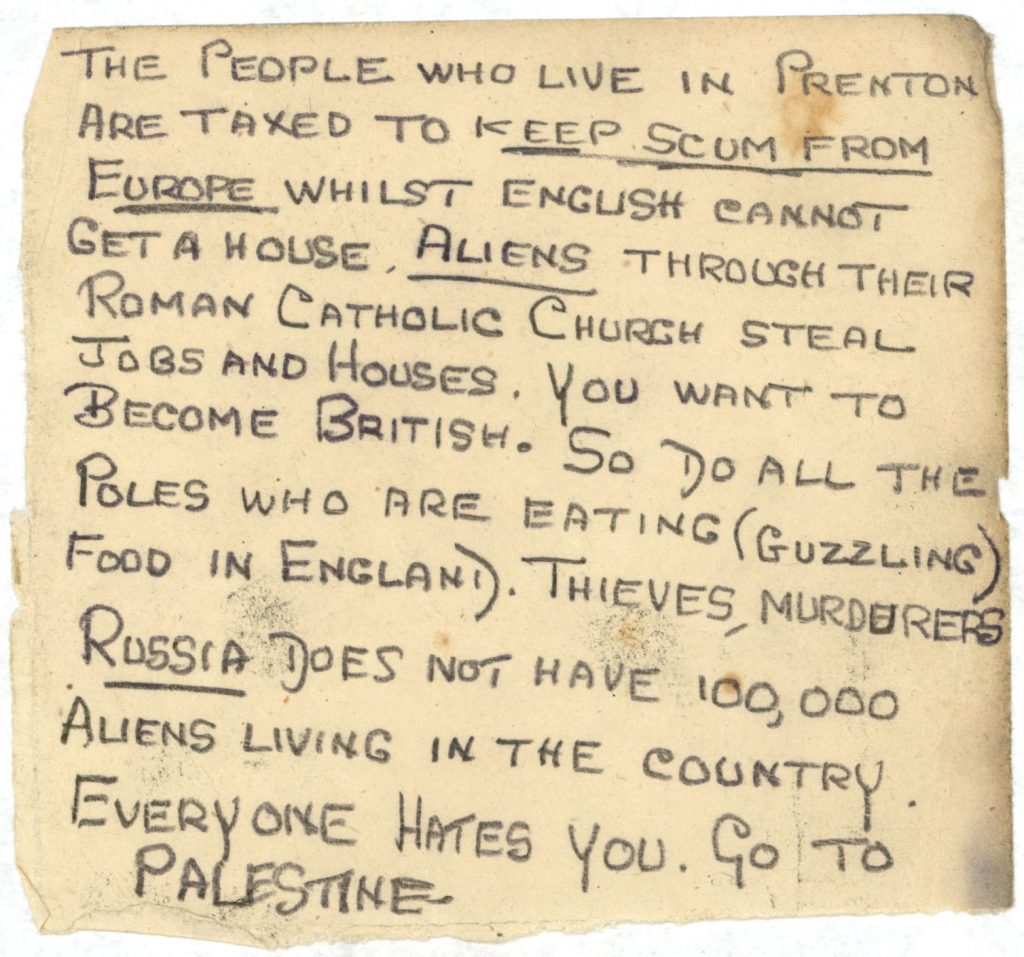

A final group, in my mind, are ephemera and other assorted materials, like news clippings. The fact that an individual or family chose to preserve these items would seem to tell us a lot of about their importance or impact. Ludwig Neumann, a German Jew, was the owner of the Neumann & Mendel clothing manufacturing business in Essen. In 1938, Neumann’s business was taken from him by the Nazis and transferred to a pro-Nazi owner. He was imprisoned at the time of Kristallnacht, and only released on the understanding that he would leave the country immediately. After his arrival to Britain as a refugee from Nazism, Neumann was interned in 1940 as an ‘enemy alien’. After his release, Neumann joined the Home Guard.

This anonymous note Ludwig Neumann received from a neighbour in Prenton around the time of his naturalisation in 1947 is rather disturbing, not only for its content but also for the fact that it has been so carefully preserved. It is tempting, for instance, to make biographical connections with his later brief return to Germany in the 1950s.

Challenges of curation

Although the new Refugee Map is designed to bring out stories from the collection, it quickly becomes evident that there is, obviously, no straightforward or definitive method of presenting the lives of the refugee individuals and families represented in our collections. A key goal of the new Refugee Map was to make the interesting but complex stories drawn from our Family Papers Collection easier for both researchers and general audiences to follow. Though the map is not curated to the extent of, say, an exhibition, there are necessarily curatorial choices made on how and what to display—and there are a number of pitfalls in trying to fit archival content within any set format, however flexible. Maps, pins and routes, which would seem to indicate exact locations, for instance, are often at odds with the incomplete or unknown information in a collection or interview. Not every collection has the same types or amounts of material, which has meant some Family Papers collections may never appear on the digital resource—one such collection, for instance, is the Adolf Wald collection, which consists only of his 1926 bar mitzvah album in Leipzig; no further information is known about him.

Equally, there are tensions between older archival interests and practices, reflected in how and what material was catalogued, and a narrative approach centred on individuals. Each Collection includes an edited version of the catalogue description; each Record includes the part of this description relating to the time period and location indicated by the pin. Notably, catalogue entries from around the 1980s are apparently focused on the family patriarch, the ‘main character’ of the collection—often there is little to no information on female family members (as is the case, for instance, with the Ludwig Neumann collection), including, disturbingly, even the name of the ‘wife’ (such as in the Loewy collection). Often these entries do not even include provenance history. As the Refugee Map is structured around individuals, I have tried to bring out more details from the materials to fill in some of these gaps where possible.

Conclusion

Though no one curatorial method is perfect, from an institutional standpoint the new Refugee Map is a vast improvement from its predecessor in terms of painting a more detailed and nuanced picture of the Jewish refugees represented in our collections. The ability to add varied content and present multiple stages of a family or individual’s journey and life as refugees opens a window into their everyday lives, including in their adopted new homes rather than focusing entirely on their lives before the Second World War. Within the first months, visitor numbers to the new resource greatly exceeded that of the old map’s audience over four years.

Initially, one hundred collections were published on the Refugee Map, and the Library will continue to add collections, both new and old, to the website. In doing so, the resource will continue to grow and change, perhaps addressing some of the persisting issues with its display and the tension between the reductive nature of narrative and the richness of our archive. We hope that our Refugee Map will draw further attention to our Family Papers Collection from researchers to develop further, in-depth projects that will help to enrich this display. The Refugee Map is one part of a larger, ambitious Digital Transformation Project at the Library that aims to revolutionise access to our archive. Over the next five years, we will catalogue and digitise thousands of pages of unique material, including collections from our Family Papers, to make it available online—both serving to preserve our most fragile items and, we hope, inspire new research in the field.

- Yi-Fu Tuan, ‘Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective’, in Philosophy in Geography, ed. by Stephen Gale and Gunnar Olsson (London: D. Reidel, 1979), pp. 387-427 (p. 387). ↩

- See for example: Anne Kelly Knowles, Tim Cole, and Alberto Giordano, eds., Geographies of the Holocaust (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press); Jaskot, Paul B. and Anne Kelly Knowles, ‘Architecture and Maps, Databases and Archives: An Approach to Institutional History and the Built Environment in Nazi Germany’, The Iris (15 February 2017). http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/dah_jaskot_knowles/; Michal Frankl, ‘Spatial Queries and the First Deportations from Slovakia’, EHRI Document Blog. 12 December 2019. https://blog.ehri-project.eu/2019/12/12/spatial-queries-first-deportations-slovakia/; Michal Frankl, ‘Reports from the No Man’s Land’, EHRI Document Blog (19 January 2016). https://blog.ehri-project.eu/2016/01/19/reports-from-the-no-mans-land/; and Arolsen Archives and NIOD’s project ‘Transnational Remembrance of Nazi Forced Labor and Migration’, see: https://transrem.arolsen-archives.org/en/home/ ↩

One Comment Leave a reply