In September 1981, in the basement of the Tübingen University, German survivors of the Sinti and Roma genocide and remembrance activists captured the racial archives created by the scientific authorities under the Nazi regime to identify, deport and destroy their families.1 The documents seized were immediately given to the German Federal Archives. Today, this vast collection is kept in Berlin under the reference R165 and is composed of thousands of documents reflecting the racial investigations conducted by a key institution decisively involved in the Sinti and Roma genocide: the Racial Hygiene Research Centre (Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle, RHF) headed by Robert Ritter.2

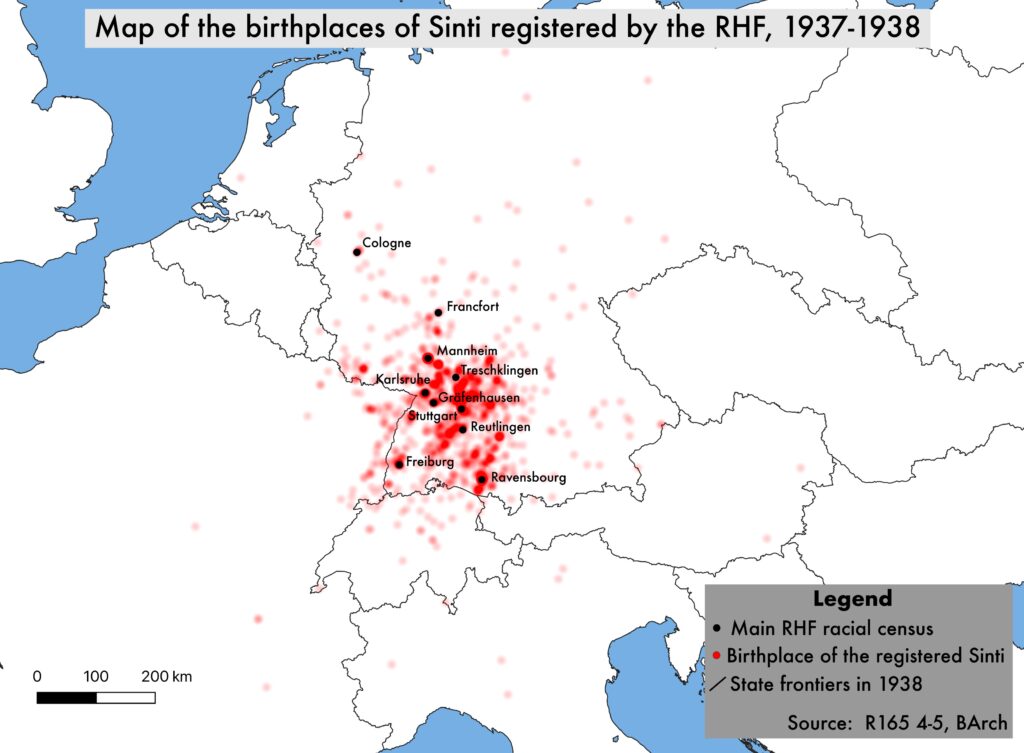

Delving into these genealogical records, police mugshots, and personal registration cards reveals the considerable efforts made by the RHF to spot and census the Sinti and Roma populations living in Germany according to racial standards. The goal of this research center was to build a complete racial database of people labelled as “gypsies”. The data and records gathered by RHF racial scientists were used by criminal police offices to implement exclusion measures, persecution actions and genocidal policies against Sinti and Roma. During my stay in Berlin as a Conny Kristel fellow, I focus on the racial documentation collected on a specific subgroup: the Sinti from the Rhineland area. Indeed, my doctoral research aims at studying the persecutions of Sinti and Roma in annexed Alsace and Moselle. As numerous families lived and circulated on both sides of the Rhine banks during the interwar period, they also faced two different registration systems and police categorizations targeting people with an itinerant lifestyle and systematically perceived as vagrant criminals to the state eyes: “nomade” in France, “gypsy” (Zigeuner) in Germany. Between 1937 and 1938, RHF anthropologists conducted several racial censuses and inquiries in multiple Rhine cities like Mannheim, Karlsruhe, Heidelberg, or Freiburg, and gathered complete social, genealogical, photographic, and anthropometric data on more than 1 000 Sinti living in the area.3 Numerous recorded Sinti had strong bonds and connections with Alsace and Moselle as these territories were German-ruled between 1871 and 1918 and constituted spaces of circulation for travelling families.

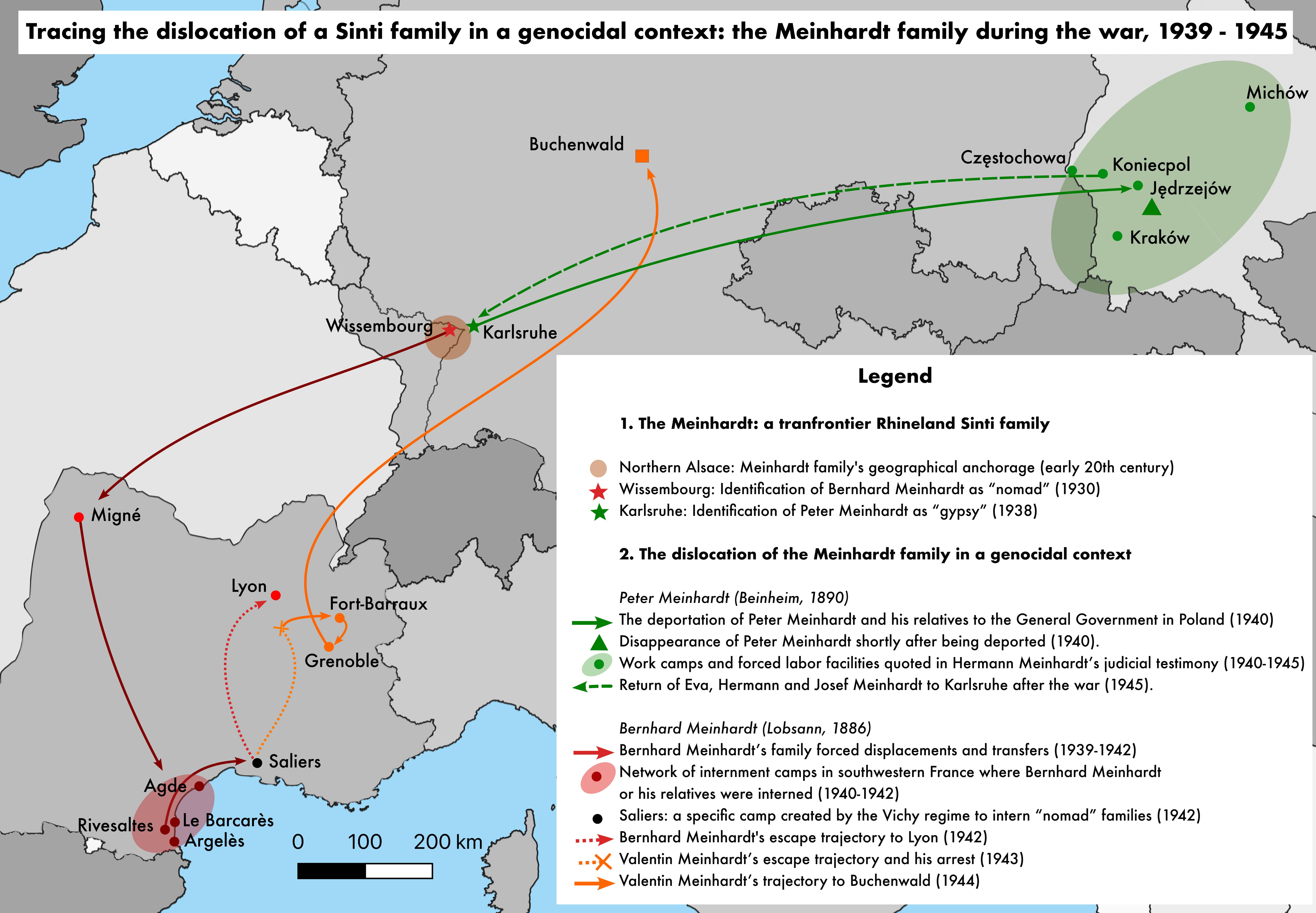

In this contribution I would like to highlight how the R165 collection can be used to document of the persecution of a transfrontier Sinti family originating from northern Alsace and present in Karlsruhe in the interwar period: the Meinhardt. As historians have pointed out, police archives regarding the Sinti persecutions in Karlsruhe remained very fragmented after 1938.4 Therefore, mobilizing the RHF racial documentation make possible to bypass the lack of sources and to explore the presence and destruction of the Sinti families living in this Rhine city during the war using the names from the racial census lists. Crossing RHF materials with French internment camps documents, Arolsen Archives records and postwar compensation files allow to map the destruction and dislocation of the Meinhardt family by following the trajectories of two brothers, Bernhard and Peter Meinhardt, respectively aged 53 and 49 in 1939.

The Meinhardt: a Rhineland Sinti family identified on both sides of the Rhine in the prewar years.

On 13 April 1938, Peter Meinhardt, born in 1890 in Beinheim, northern Alsace, was registered during a racial census conducted by the RHF racial anthropologist Adolf Würth.5 On that same day, his wife Eva Weiss and their two children, Hermann and Josef, were also censused with numerous other Sinti individuals, labelled as “gypsies”. The data collected on the Meinhardt family during this operation indicate that they lived in the Waldhornstraße, a street located in the Dörfle district, a popular neighborhood where many of the Karlsruhe Sinti families were forcibly settled by the municipality in the mid-1930s. On 13 February 1964, in a sworn testimony before the regional Karlsruhe Court of Justice, the survivor Hermann Meinhardt, Peter’s son, described the conditions of the specific census conducted by the RHF in the headquarters of the Karlsruhe police department:

“One day in 1939 or 1940 [in fact 1938], we were summoned to an official building on the Marktplatz. I don’t know exactly whether it was the police or the district office. We were summoned family by family and probably also according to the location of the apartments. In any case we, the Meinhardt family together with the Weiss family, were summoned. We then went into a room one by one. There sat a man, who, supported by a young girl, determined our hair color – exactly according to a pattern sample –, the shape of our head, our nose, and the color of our eyes. As we learned later, this man was from the Race Policy Office [In fact Racial Research Hygiene Center]. He knew things about us, Gypsies [Zigeuner]. He knew some of our nicknames and some words of our language.”6

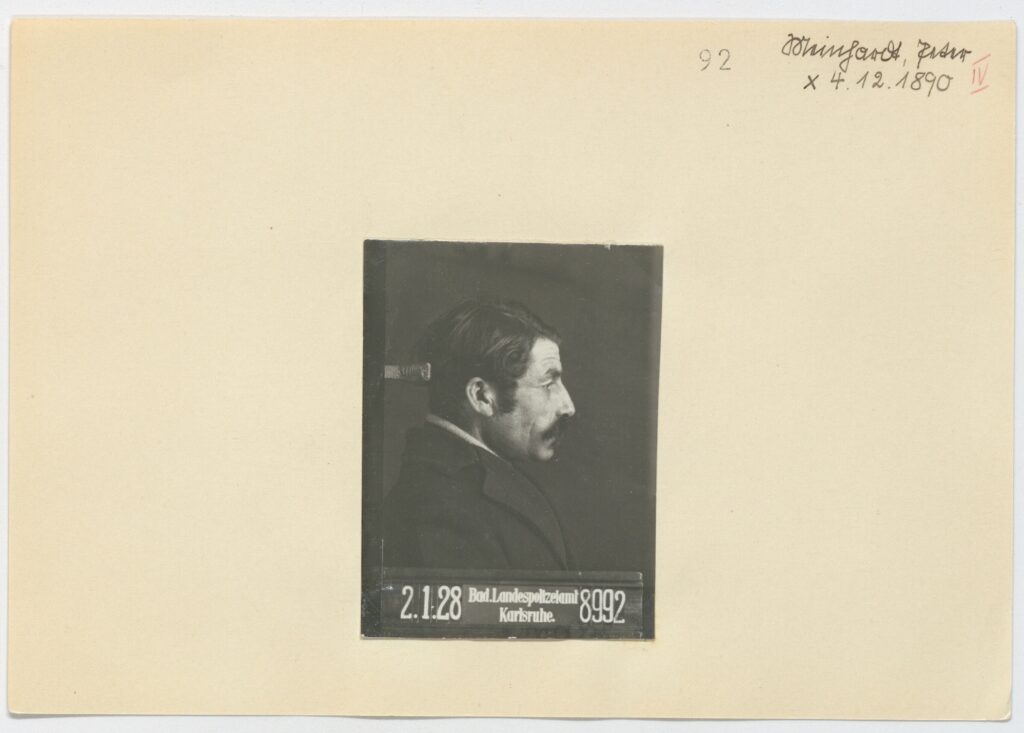

On his RHF registration card created in 1938, Peter Meinhardt was recorded as a violinist affiliated to the Reich Chamber of Music (Reichsmusikkammer) and as a veteran of the First World War. The presence of this family in Karlsruhe is attested from 1928 as a mugshot of Peter Meinhardt was took by the identification service of the Baden criminal police (Landeskriminalamt) in January 1928.7 In 1937, for his genealogical and anthropometric investigations on site, Adolf Würth worked closely with local criminal police records on Sinti and Roma with the permission of Paul Werner, former head of the Baden criminal police and responsible for implementing “crime prevention fighting” policies within the newly created Reich Criminal Police Office (Reichskriminalpolizeiamt, RKPA). Werner was highly interested in RHF’s racial and genealogical research on Sinti and Roma as he instigated a biological and hereditary conception of crime and social deviancy.8 During his racial inquiries, Würth identified Peter as the son of Anton Meinhardt and Karoline Reinhardt, an itinerant family who travelled in Alsace before the First World War, when this territory was still part of the German empire (Kaiserreich).

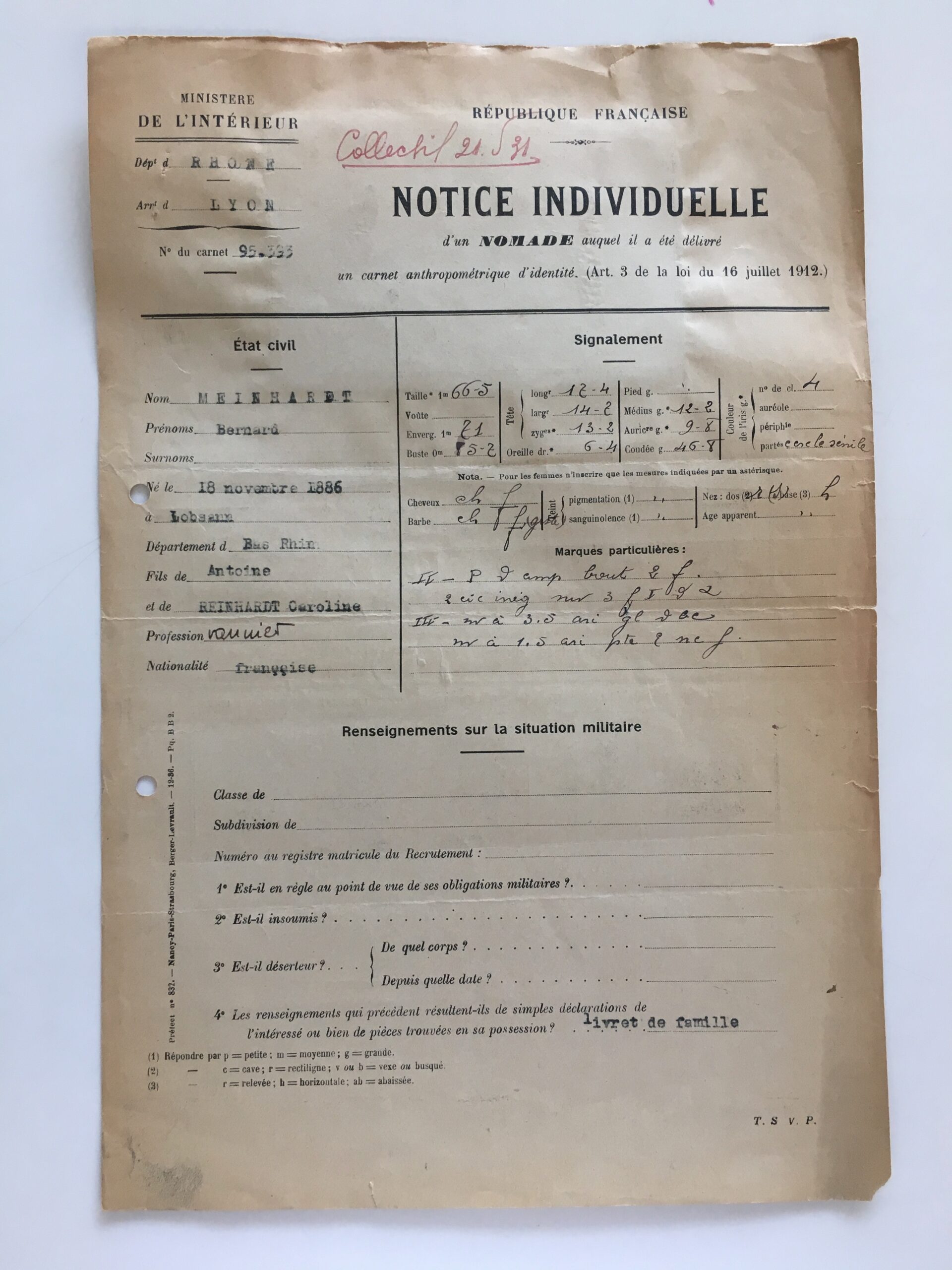

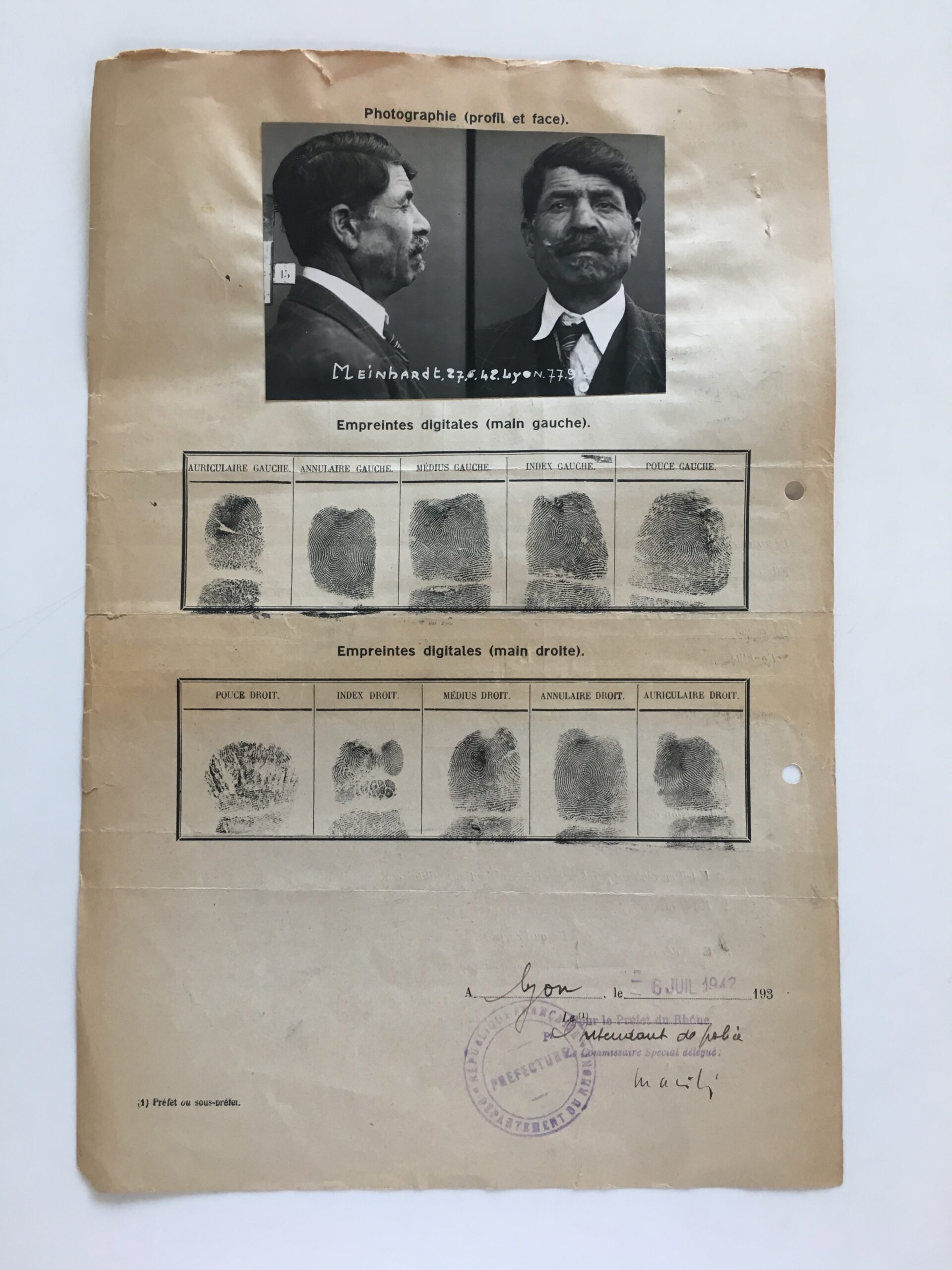

Bernhard Meinhardt, Peter’s brother, was born in northern Alsace in 1886. On his birth certificate issued by the municipality of Lobsann, it is indicated that his parents lived in a trailer (Wohnwagen).9 The familial anchorages of the Meinhardt brothers are deeply rooted to the Alsatian territory: in 1864, their mother was born in Meistratzheim, near Strasbourg. During the First World War, the Meinhardt family fled to Germany where Bernhard and his wife Thérèse had a son in 1916 in Kassel. After the war, while Peter and Eva Weiss stayed in Karlsruhe, Bernhard came back to France and travel as an itinerant musician in northern Alsace. During the 1930’s, he and his relatives were identified as “nomads” by the French authorities, forcing them to carry an anthropometric identity booklet which allowed the police to track their movements.10 According to the birthplaces of their children, Bernhard and Thérèse Meinhardt travelled in northern Alsace, between Wissembourg and Haguenau, in the interwar period.

The case of the Meinhardt family illustrates the interweaving connections between the two banks of the Rhine valley during the interwar period. The Rhine area was a shared and experienced space for Sinti communities woven together by familial and affective relationships. On both sides of the frontier, Sinti were subject to distinct identification procedures and surveillance measures by both the German and French authorities who projected onto this borderland territory their own conception of “gypsiness”. At the end of the 1930’s, Bernhard and Peter Meinhardt were each labelled with a specific police category: “nomad” for the first, “gypsy” for the second. As soon as the war broke out between France and Germany in September 1939, they faced different persecution policies that led to the dislocation and destruction of the Meinhardt family.

Mapping the persecution trajectories of the Meinhardt brothers during the war

With the war declared between France and Germany in September 1939, the French side of the Rhine border was evacuated from its civilian population. Faced with a large influx of refugees from Alsace, the French authorities decided at the end of September to sort out the evacuees and lock up and concentrate the “nomads” from this territory in an internment camp.11 On 28 November 1939, Bernhardt Meinhardt’s family was part of a specific evacuation convoy only composed of itinerant musicians from the Haguenau area, labelled as “nomads”. They were sent to the Indre department before being transferred to the Agde camp as their names appeared on an internee’s list dated from December 1940.12 On 15 January 1941, they were confined in the Rivesaltes camp, a major internment camp near Perpignan used by the Vichy regime to intern ‘undesirable’ individuals such as foreign Jews from Germany and Central Europe and other categories of refugees.13 Evacuated from Alsace and interned in south-western French camps as “nomads”, the Meinhardts faced very difficult living conditions, camp administration violence and familial separation: Johann, Bernhard’s son, was sent to the Vernet repressive camp in March 1941 after an escaping attempt. In last May 1941, Bernhard and Thérèse managed to escape from Rivesaltes with one of their daughters, Philippine.

At the same time, on the German side of the Rhine bank, Peter Meinhardt’s family living in Karlsruhe was targeted by the first collective deportation towards Sinti and Roma in Western Germany. On 27 April 1940, Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, RSHA) launched a major police action to deport 2 500 “Gypsies” from Western Germany to the General Government in Poland.14 This coordinated operation aimed at creating a “Gypsy-free” (Zigeunerfrei) zone to prepare the German military offensive in Western Europe. Paul Werner was the logistical coordinator of this mass deportation operation planned for mid-May whereas the RHF researcher Adolf Würth was present at the preparatory police discussions for organizing the transports.15 The close cooperation between police authorities and racial scientists to implement deportation measures and genocide policies against Sinti and Roma highlights what Michael Zimmerman conceptualized as a “scientific-police complex’.16 From the Baden area, he estimates that nearly 500 people were deported in mid-May 1940 including Karlsruhe.17 Registered as “Gypsies” in 1938, Peter Meinhardt, his wife Eva Weiss and their two children Hermann and Josef were rounded up by the Karlsruhe criminal police and transferred to the Hohenasperg prison where Adolf Würth carried out further racial examinations on arrested Sinti families and proceeded to the selections for the deportation according to the RHF racial standards. In 1962, Hermann Meinhardt remembered the conditions of his deportation:

“Some time after this investigation [the Karlsruhe 1938 racial census] we were summoned to the same office. There all the Gypsies I knew were gathered in the courtyard. Our papers were taken from us and in exchange we were given a card with the inscription “Gypsy mongrel” (Zigeunermischlinge). We were loaded […] into police cars and driven to Hohenasperg. We had not been informed beforehand that we would be taken away. We therefore had no luggage, no eating utensils, blankets, or other items with us, except what we were wearing on our bodies. […] We stayed at Hohenasperg for 8 days and were then transported to Poland.”18

In the General Government, the deported Sinti were partly left to their own devices, partly assigned to forced labor in camp and ghettos where it is estimated that only 20 percent survived through the war.19 Peter Meinhardt was separated from his family shortly after being deported to Poland and his relatives never heard from him again.20 It is very difficult to understand the complete trajectories of the Meinhardt family in the General Government as the situation was chaotic and contemporary sources remain extremely fragmented. However, in a postwar testimony given for a relative’s compensation claims case, Hermann Meinhardt cited the different places he’s been through – Jędrzejów, Michów, Krakau, Częstochowa – and described the harsh conditions of forced labor – mainly road building –, constantly under the surveillance of police guards inside work camp facilities surrounded by barbwire.21 Hermann, Josef and Eva were liberated by the Soviet forces in January 1945 in Koniecpol and came back to Karlsruhe after the war where they faced the disappearance of their relatives from the Dörfle district. Indeed, in spring 1943, German police authorities decided to organize a new genocidal action by deporting all Sinti and Roma still living in Germany and annexed territories to Auschwitz-Birkenau.22 This mass deportation operation also affected the Sinti families still present in Karlsruhe in 1943.

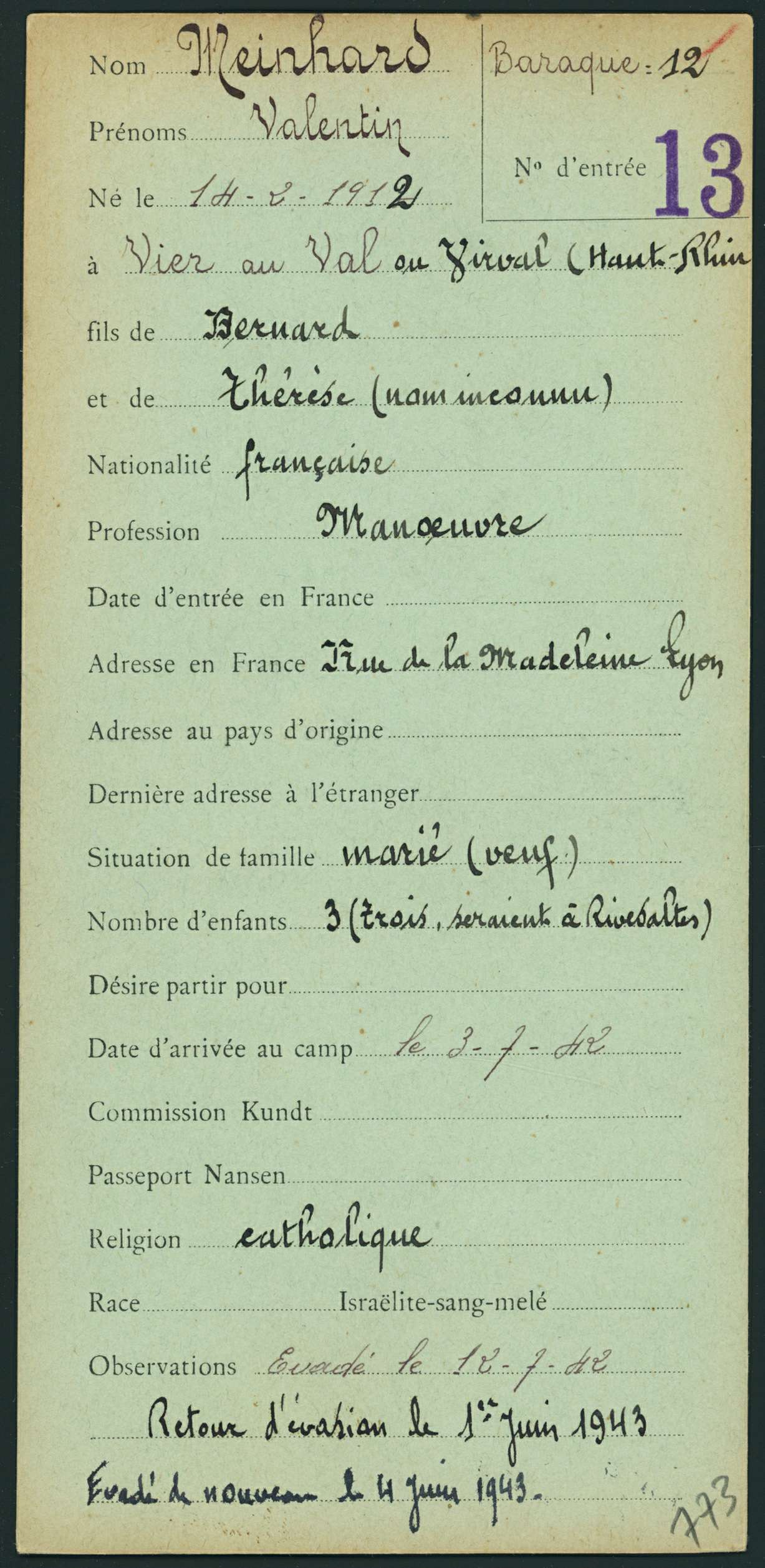

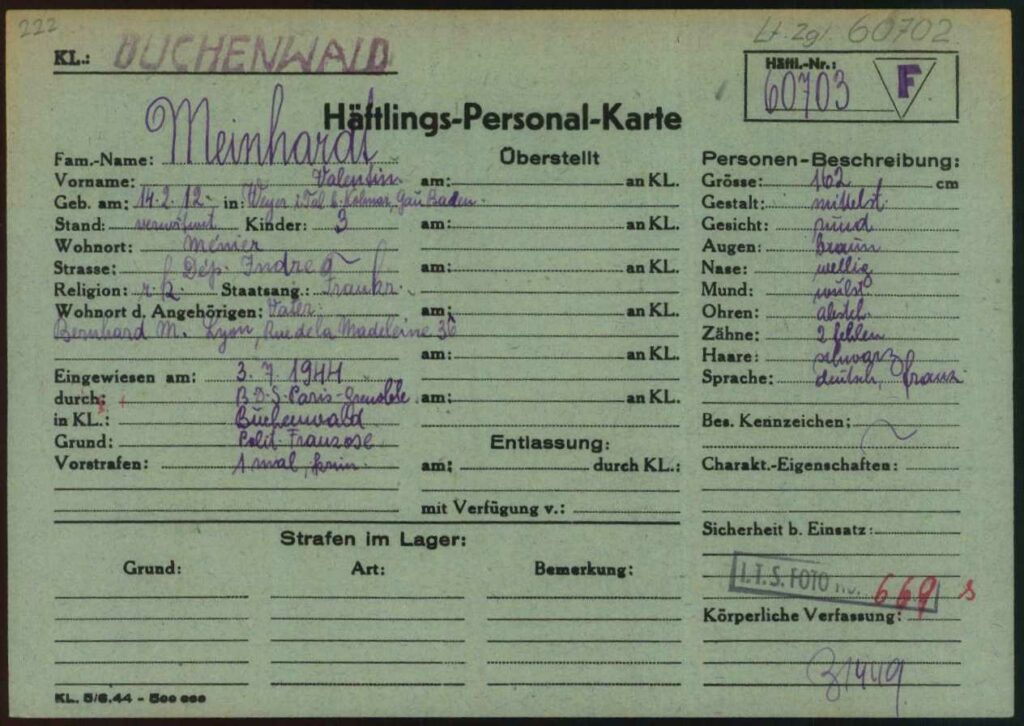

In Vichy France, the fugitives Bernhard Meinhardt and his wife were arrested near Lyon and sent back to the Rivesaltes camp in August 1942. Few days later, Bernhard was separated from his family and transferred near Arles as a forced worker to build a new camp only dedicated for “nomads”, the Saliers internment camp. In early 1942, the Vichy authorities decided to create this specific camp to separate “nomad” families from the other categories of internees and to concentrate them on a single site. There, Bernhard immediately escaped from Saliers and survived clandestinely in Lyon through the war. But his son, Valentin, who was also interned in Agde, Rivesaltes and Saliers where he escaped several times, was transferred in retaliation to Fort-Barraux, a repressive camp near Grenoble in June 1943.23

Anthropometric “nomad” form, Bernard Meinhardt, Lyon, 1942, 540W 214, Archives départementales du Rhône.

Internee registration card, Valentin Meinhardt, Saliers, 142W 98, Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône.

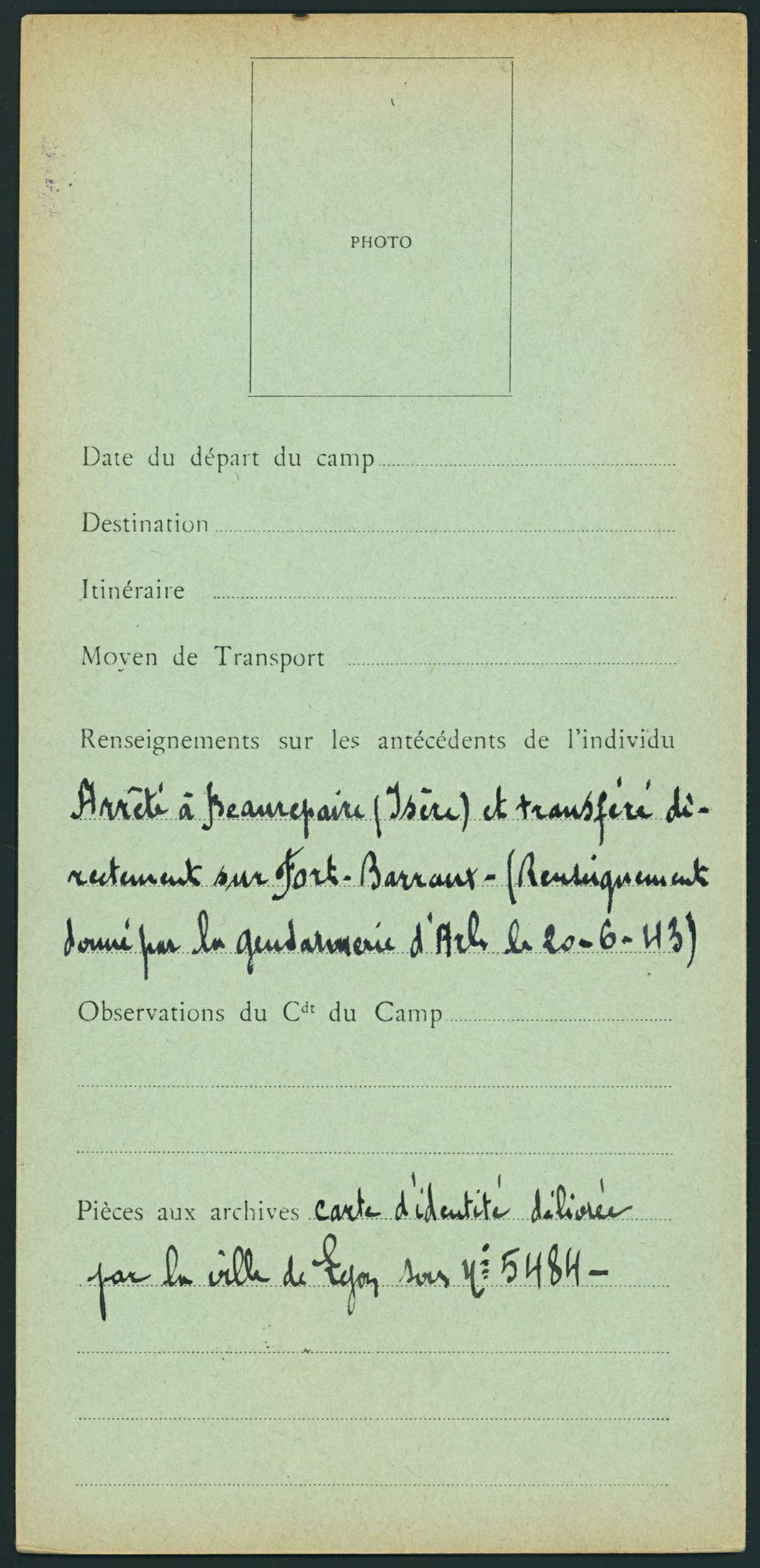

From there, he was transferred to Nexon, a camp in Haute Vienne, and worked on the Todt construction sites in Charente-Maritime.24 In June 1944, Valentin Meinhardt was sent back to Fort-Barraux and on 22 June 1944, he was part of a deportation convoy from Grenoble to Buchenwald composed of political prisoners with some former internees of the Saliers internment camp.25 There, he was assigned to several working Kommandos such as the Weferlingen Kommando in August 1944.26 Liberated in January 1945 by American troops, Valentin Meinhardt came back to Alsace after the war.

Conclusion

Racial research conducted by RHF anthropologists from 1937 to 1940 resulted in the building of extensive family trees dedicated to Sinti and Roma genealogies. These materials were used by the criminal police authorities to spot and deport individuals labeled as “Gypsies” and to achieve the Sinti and Roma genocide. Today, studying this vast collection kept in the German Federal Archives, allow us to identify and connect different Sinti and Roma families between them. Civil status, family ties, occupations, social backgrounds, or address are the main information kept in these files that the historical research can grasp to map their multiple presence before 1940 in Germany despite the lack or fragmentation of the remaining regional sources as it was for Karlsruhe. To understand how a racial scientific institution concretely works to build a central register dedicated to census of a specific population defined on biological criteria, the R165 collection is a textbook case and illustrates how the German authorities conceived the “Gypsy question” (Zigeunerfrage) at that time.27

However, the R165 collection cannot, it itself, be regarded as the ultimate proof of the immensity and intensity of the genocide committed towards Sinti and Roma and can only make sense in a network of other regional sources to document persecution, deportation, and destruction of these families on a European scale. Cross-referencing this database of the persecuted with other holdings such as the Arolsen archives or post-war compensation files makes it possible to name the victims and retrace their persecution trajectories in a genocidal context

Concerning Alsace, the RHF archives of the 1938 Karlsruhe racial registration shows the strong familial bonds of Sinti living on the two sides of the Rhine, between Alsace and Baden, since the second part of the 19th century at least. In this regard, the trajectories of the Meinhardt brothers during the war highlights the fact that a same family could be confronted to two discriminatory state registration systems and parallel persecution regimes that led to their dislocation and destruction across Europe, from southwestern France to the General Government in Poland.

Hermann and Valentin Meinhardt were cousins and two survivors of the Sinti and Roma genocide. The first was deported to Poland as a “Gypsy”, faced the disappearance of his father Peter and experienced forced labor in extremely harsh conditions. The second was transferred to several internment and repressive camps in southern France dedicated to “nomad” and was later deported to Buchenwald with French political prisoners. These trajectories underline the intertwining of persecution systems towards Sinti and Roma in Europe, between France and Poland, towards an itinerant family of musicians who originally came from Northern Alsace. The strong family ties that united the Alsatian and Rhineland Sinti make the genocide a traumatic event shared today on both sides of the Rhine.

- For a history of this archival collection and its links with the German Sinti and Roma civil rights’ movements, see: Josef Henke, « Quellenschicksale und Bewertungsfragen. Archivische Probleme bei der Überlieferungsbildung zur Verfolgung der Sinti und Roma im Dritten Reich », Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 1993, vol. 41, n°1, 61‑77, Daniela Gress, “Sinti und Roma in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland”, in: RomArchive, Sektion Bürgerrechtsbewegung der Sinti und Roma, 2019, accessed 25.6.2022: https://www.romarchive.eu/de/roma-civil-rights-movement/sinti-and-roma-federal-republic-germany/. ↩

- The author dedicates this text to the memory of Zilli Reichmann (1924-2022) who passed away on 21 October 2022. Arrested and deported from Strasbourg in 1942, Zilli Reichmann was a survivor of the Sinti and Roma genocide, a tireless witness of the racial persecutions and a civil rights fighter for state recognition and claim reparations. The author would like to thank Nicolai M. Zimmermann and the staff of the Berlin-Lictherfelde Bundesarchiv for their support during his research stay. Thanks also to Ari Joskowicz, Michala Lônčíková, and the EHRI Blog team for their help and proofreading to this contribution. ↩

- “Hilfskarteien: Sinti aus Süddeutschland, Rheinland, Mitteldeutschland”, 1937-1940, R165 6, Bundesarchiv, Berlin-Lichterfelde. ↩

- Michail Krausnick, Abfahrt Karlsruhe: 16.5.1940. Die Deportation der Karlsruher Sinti und Roma, Ubstadt-Weiher, Verlag Regionalkultur, 2015 (1990) ; Johannes Kaiser, Verfolgung von Sinti und Roma in Karlsruhe im Nationalsozialismus. Die städtische und kriminalpolizeiliche Praxis, Karlsruhe, Info Verlag, 2020 ; Vanessa Hilss, Sinti und Roma: « Nicht aus Gründen der Rasse verfolgt »? ; zur Entschädigungspraxis am Landesamt für Wiedergutmachung Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Info Verlag, 2017. ↩

- RHF registration card of Peter Meinhardt, 13.4.1938, Karlsruhe, R165 12, BArch. On Adolf Würth, see: Joachim S. Hohmann, Robert Ritter und die Erben der Kriminalbiologie. « Zigeunerforschung » im Nationalsozialismus und in Westdeutschland im Zeichen des Rassismus, Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, 1991, 275-296. ↩

- Judicial hearing of the witness Hermann Meinhardt, 13.2.1964, 32, in: Maria Weiss reparation claim, 480 Nr. 3093/2, Generallandesarchiv Karlsruhe (GLAK). Translation by the author. ↩

- Criminal police mugshot, Peter Meinhardt, Karlsruhe, 2.1.1928, R165 52, BArch. ↩

- On Paul Werner, see: Michael Wildt, Generation des Unbedingten: das Führungskorps des Reichssicherheitshauptamtes, Hamburg, Hamburger Edition, 2002, 314-321. ↩

- Birth certificate of Bernhardt Meinhardt, 18.11.1886, Lobsann, 4E 271/14, Archives d’Alsace, site de Strasbourg. ↩

- Issuance of an anthropometric identity booklet to Bernhard Meinhardt, Wissembourg, 31.12.1930, 264D 54, ADBR. ↩

- Circular of the Ministry of Interior of the Vichy regime regarding internment policies for refugees, 28.9.1940, 765W65, Archives départementales de la Haute-Vienne. ↩

- Internee’s list, Agde, December 1940, 2W 260, Archives départementales de l’Hérault. ↩

- Entry register, Rivesaltes, 15.1.1941, 1260W78, Archives départementales des Pyrénées-Orientales. ↩

- For an overview of the deportation of May 1940, see : Michael Zimmermann, Rassenutopie und Genozid: die nationalsozialistische « Lösung der Zigeunerfrage », Hamburg, Christians, 1996, 574 p., 167-175. ↩

- Benno Müller-Hill, Tödliche Wissenschaft. Die Aussonderung von Juden, Zigeunern und Geisteskranken, 1933-1945; Reinbek, Rowohlt, 1984, 153-154. ↩

- Michael Zimmermann, Rassenutopie und Genozid, op. cit., 147-155. ↩

- Ibid., 174. ↩

- Judicial hearing of the witness Hermann Meinhardt, 13.2.1964, 32, in: Maria Weiss reparation claim, 480 Nr. 3093/2, GLAK. Translation by the author. ↩

- Karola Fings and Ulrich Opfermann (dir.), Zigeunerverfolgung im Rheinland und in Westfalen: 1933 – 1945. Geschichte, Aufarbeitung und Erinnerung, Paderborn, Schöningh, 2012, 345. ↩

- Letter from the Gerhard Caemmerer Law Firm to the Reparation Claim Office of Karlsruhe, 16.7.1955, 66, in: Peter Meinhardt reparation claim, 480 Nr. 14744, GLAK. ↩

- Judicial hearing of the witness Hermann Meinhardt, 5.12.1952, 81, in: Josefine Kling reparation claim, 480 Nr. 1374/3, GLAK. Translation by the author. ↩

- Karola Fings, « A “Wannsee Conference” on the Extermination of the Gypsies? New Research Findings Regarding 15 January 1943 and the Auschwitz Decree », Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust, 2013, vol. 27, no 3, p. 174‑194. ↩

- Internee registration card, Valentin Meinhardt, Saliers, 142W 98, Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône. ↩

- For a more detailed biography of Valentin Meinhardt during the war, see: Mémorial des Nomades de France, “Valentin Meinhart”, accessed 25.6.2022: http://memorialdesnomadesdefrance.fr/valentin-meinhart-1912-%E2%80%A0-1968/ ↩

- Prisoner registration card, Valentin Meinhardt, Buchenwald, 6604823, 1.1.5./ITS Digital Archives, Archives Nationales. ↩

- Labor assignment card, Valentin Meinhardt, Buchenwald, 6604825, 1.1.5./ITS Digital Archives, Archives Nationales. ↩

- On this issue, the lecture given by Adolf Würth in September 1937 at the University of Tübingen sheds light on how he conceived his work for the RHF. Through a rhetoric focused on the obsession of protecting the German blood, Würth detailed the methods used by the RHF to assess Sinti and Roma racial affiliations and promoted a biological and genealogical approach of the “Gypsy question”. See Adolf Würth, “Bemerkungen zur Zigeunerfrage und Zigeunerforschung in Deutschland”, Verhandlungen der Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rassenforschung, 1938, n. 9, 95-98. ↩