For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

I was born in Kharkiv in 1950 and it is likely that I was the first Soviet historian to begin the study of the Holocaust, even though the subject was effectively banned. I was also the first who managed to publish articles on it – abroad. Since 1984, I have published twenty monographs and collections of documents, fifty-two scholarly articles and over 1,100 detailed encyclopedia entries. About a quarter of my publications deal with Poland, the Baltic countries, Belarus and Russia, but they mainly deal with the Holocaust in Ukraine. At the invitation of EHRI, I describe here my experiences as a historian seeking to access, to study and sometimes to publish Soviet documents as well as other records and interviews held in Germany, France, Israel, and the United States.

While a student at the history department of Kharkiv State University in Soviet Ukraine in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I studied the Soviet historiography of the Second World War. It struck me that in these studies, the tragedy that befell the Jewish population of the USSR (including Ukraine) was a topic which in the Soviet Union was not officially forbidden, but at the very least not recommended. The Nazi genocide against the Jews was virtually silenced. For almost 45 years after the end of the war, not a single specialized study appeared in print in the Soviet Union on the subject. Works analyzing the occupation regime provided at best a few facts about the murder of Jews, without recognizing the special nature of the Nazi actions against them. The occupiers and their collaborators were allegedly exterminating not Jews but “Soviet citizens”, and the fate of Jews was no different from that of the Soviet citizens of other nationalities – such was the leitmotif of these works.

In my opinion, this attitude towards the tragedy of the Jews of the USSR was nothing but a manifestation of antisemitism, which although it was verbally condemned it was in fact tacitly encouraged, especially from the late 1960s, when the Soviet leadership sided with the Arab countries in their military conflict with Israel. All this could only heighten my interest in the subject of the Holocaust – as we all know, the forbidden fruit is the sweetest. This interest did not disappear even when I could not find a single publication on the subject in the USSR, or even a single Soviet historian who had studied the subject and whom I could consult. I had to do everything myself.

After much time was spent and many efforts were made to gain access, I eventually did find some scholarly literature on the Holocaust in the “special collection” of the Library of Foreign Literature in Moscow. These were primarily books published in the 1950s and 1960s by Gerald Reitlinger (The Final Solution: The Attempt to Exterminate the Jews of Europe 1939-1945), Leon Poliakov and Joseph Wulf (Das Dritte Reich und die Juden), Reimund Schnabel (Macht ohne Moral), Raul Hilberg (The Destruction of the European Jews), Hans Buchheim/Martin Broszat/Hans-Adolf Jacobsen/Helmut Krausnick (Anatomie des SS-States), Hannah Arendt (Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil) and Alan Bullock (Hitler: A Study in Tyranny). These books allowed me to orient myself within the subject and to acquire basic knowledge about it. However, I was also somewhat disappointed. These books contained very little information about the Holocaust in the Soviet Union. Then again, this was also understandable; the authors had no access to Soviet archives and did not know the Russian language, while the vast majority of the Soviet documents were in Russian.

Analyzing early Soviet publications

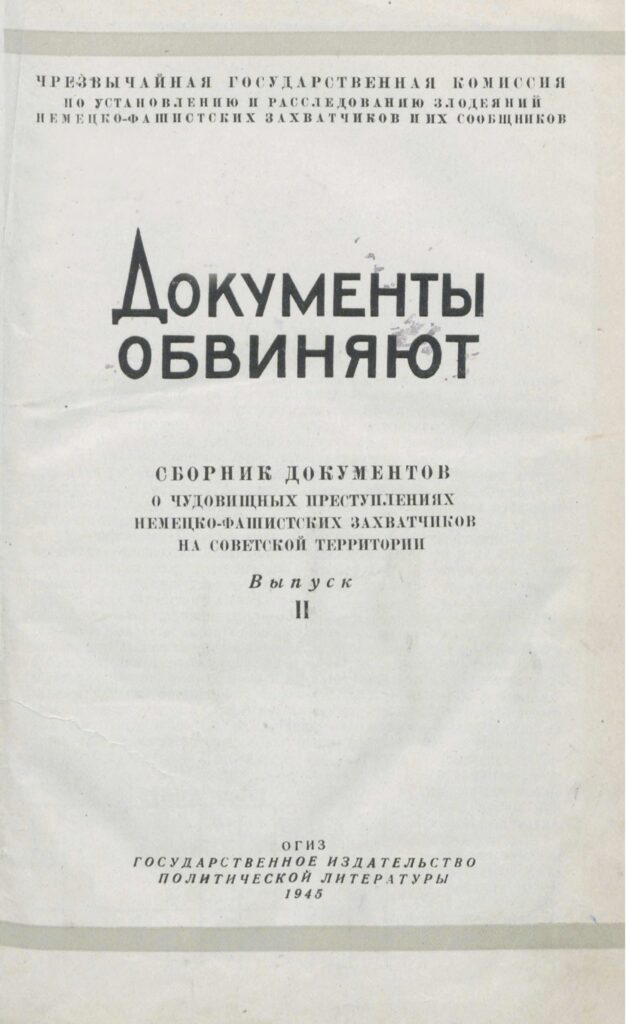

These foreign authors could not use the document collections on the Nazi occupation regime published in the USSR in the 1940s, where references to the extermination of the Jewish population could be found, as I noted when studying them carefully. Thus, in the second volume of the collection The Documents Charge. A Collection of Documents on the Monstrous Crimes of the German Fascist Invaders on Soviet Territory (which today is available online)1, published in 1945 by the Extraordinary State Commission for the Establishment and Investigation of the Crimes of the German Fascist Invaders and Their Associates (or ChGK)2, I found translated German documents about the extermination of the Jewish population in Stavropol Krai, Krasnodar Krai and the city of Kharkiv.

I also found documents on the persecution and extermination of Jews in the fifteen issues of the brochures entitled Atrocities of the German Fascist Invaders, published between 1942 and 1945 (and now largely available online).3

When comparing these documents with documents on the extermination of non-Jewish civilians, the special character of Nazi actions against the Jews caught my eye. While the non-Jewish population was exterminated for political reasons (for being communists, Soviet activists, partisans and underground members, supporters of partisans, partisan families, as retaliation for the death of German soldiers or for acts of diversion or sabotage, or for refusing to go to Germany, for not giving up food and so on), the Jews were exterminated en masse simply because they were Jews. Soviet historiography ignored this essential difference. It made me think and led me to embark on a serious research study of the Holocaust. I carefully studied all these collections of documents and made handwritten and then typewritten copies of the documents that were of interest to me.

Documents in the Soviet archives

In the Soviet Union it was quite difficult to gain access to the relevant unpublished archival documents for research purposes. Access to the ChGK documents about Nazi crimes preserved in Soviet archives, mainly today’s State Archive of the Russian Federation, or GARF, in Moscow4, was restricted, and required prior permission from the KGB. I had to resort to all sorts of subterfuge to obtain this permit, Form No. 3. The form was issued by the first department (secret department) of the institute where I was working, the Department of Philosophy at the Kharkiv University of Radio Electronics. To get the permit, I had to fill out an application and then pass a background check. After the work in the archive, I had to hand the form back to the first department.

It was from studying the ChGK records in Moscow from 1970 to 1990 that I eventually drew a number of quantitative conclusions, which subsequent research in local Soviet and, still later, in foreign archives, only confirmed. One conclusion I drew was that in mid-1941 there were about 2.7 million Jews in Ukraine within its present-day, internationally recognized borders, which meant that based on these numbers in Europe it was not Poland (when considered within its current borders), but Ukraine that ranked first in the number of Jewish inhabitants. Globally, Ukraine came second after the United States. Another conclusion was that between 1941 and 1944, Ukraine again ranked first in Europe, this time by the number of Jewish victims. The German and Romanian occupiers and their accomplices exterminated about 1.6 million of Ukraine’s Jews. In addition, I concluded that these dead were about 60 percent of the prewar number of Jews in Ukraine. And, finally, the Jews of Ukraine who died unnatural deaths also constituted about 60 percent of the wartime dead among all civilians in Ukraine.

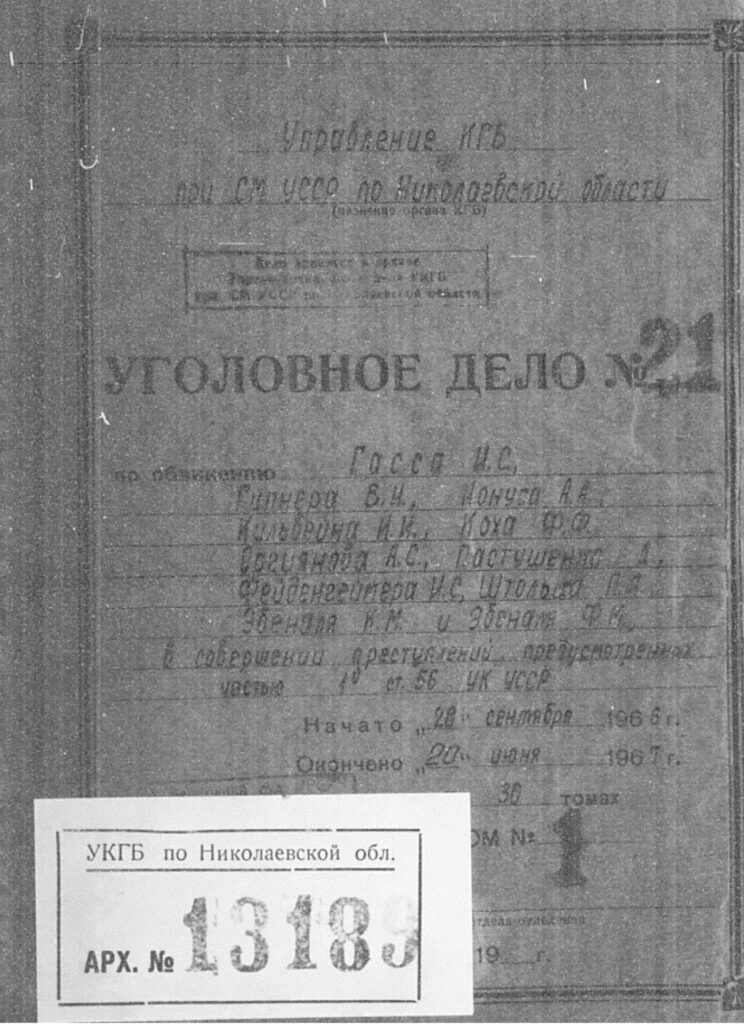

As for the KGB archives, it was practically impossible to get access to the documents there. And it was in these archives that investigative files on the former collaborators of the occupiers were kept. These contained much valuable information about the persecution and extermination of Jews. Nevertheless, through informal contacts, I managed to obtain some documents from the KGB’s holdings in Ukraine.5

Sending articles abroad

I used my findings based on the Soviet source publications and Soviet state archives to write my first articles. In those years, writing them was, as it was called then, a “desk job”. The results could not be presented in the USSR, for the reasons I outlined above. Therefore, I published my first articles on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union abroad, in East Germany (GDR) and Poland. Although considered socialist countries, part of the Soviet sphere of influence, the GDR and Poland did not share the Soviet policy of near-total silence on the Holocaust.

Thus, in 1984 my first article on the Holocaust appeared, on the deportation of Jewish Germans to the east, in German, in the Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft published in East Berlin.6 My second published article, in 1989 in the Bulletin of the Jewish Historical Institute in Poland, was in Polish, and dealt the with the deportation of Jews from the Galicia District to the Bełżec death camp.7

Meanwhile, I also attempted to publish in the so-called capitalist world. In 1984, I submitted an article to the journal Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte of the Institute for Contemporary History (Institut für Zeitgeschichte; today, the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History, an EHRI partner). In this article, I argued that the Nazis had not exterminated as many as four million people in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, as the Soviet regime claimed and as the monument there also stated. I sent the manuscript to Munich by post (computers, internet and email did not exist back then), but it never arrived. I sent it a second and third time, with the same results. As I found out, the KGB checked all mail to “capitalist” countries and confiscated, without explanation, anything that did not correspond to the Soviet point of view.

The late 1980s

In the late 1980s, during the perestroika, the attitude of the Soviet authorities towards Holocaust studies became less rigid. But even then, probably out of inertia, the editors of academic journals continued to treat the Holocaust with apprehension. Thus, when I submitted an article about the extermination of foreign Jews in Ukraine to Ukraïns’kyi istorychnyi zhurnal (Ukrainian History Journal, Kyiv) in 1988, the editorial board led by Mykhailo Koval agreed to publish it on the condition that I would change the “foreign Jews” in the title to “foreign citizens” and would add non-Jewish foreign victims to the main text. I did this, and the article was published in Ukrainian in 1989 under the title “The Annihilation by the Fascists of Foreign Civilians on the Occupied Territory of Ukraine (1941-1944)”.8

I was still not allowed to work toward a dissertation on the scholarly analysis and criticism of antisemitism: I was strongly advised to change the subject. In the end, the topic of my kandydat dissertation in philosophy in 1989 was (in Russian) “Racism as a Social Phenomenon”. And access to documents in Soviet archives continued to be problematic.

Around the same it, it became possible to obtain the documents I wanted from “capitalist” countries. In the late 1980s, for instance, I repeatedly requested such documents from various prosecutors’ offices in the Federal Republic of Germany, which were investigating Nazi crimes. Without fail, I received all the documents I needed from them – the KGB did not interfere.

The Emergence of a Ukrainian school of Holocaust studies

When in 1991 the totalitarian Soviet regime collapsed and independent states were formed, Ukraine created favorable conditions for Holocaust studies. Archives became accessible, including those of the former KGB. It was then that books and articles on the Holocaust began to be published, several dissertations on the subject were defended, and two centers for Holocaust studies were founded. One was the Tkuma Research and Education Centre for Jewish History and Culture in Dnipro, now the Tkuma Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies.9 It issues a monthly bulletin (Tkuma) and since 2002 an academic journal, Problemy Holokostu (Problems of the Holocaust). The second NGO was the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies in Kyiv10, which since 2002 issues an academic bulletin Holokost i suchasnist’ (Holocaust and Modernity) and since 2004 publishes an academic journal, under the same title, Holokost i suchasnist’. It organizes regular scholarly conferences on the Holocaust.

This way, in Ukraine a national school of Holocaust studies gradually emerged. There were inevitable difficulties, primarily due to the fact that Ukraine had been studying the problem for only thirty years, as compared to more than 75 years in the West. (Another early student of the Holocaust in Lviv was Yakov Khonigsman, 1922-2008). Today, the circle of domestic experts on the Holocaust – including among others Anatoly Podolsky, Vitaly Nakhmanovych, Oleksii Honcharenko, Tetiana Yevstafieva, Felix Levitas, Albert Wenger, Yuri Radchenko and Mark Goldenberg – is still rather narrow. Moreover, not all of them have sufficient scholarly training to ensure a high level of research, they often work in isolation, and although attempts to coordinate their scholarly research have recently been made, these are not always effective.

Publishing scholarly surveys

Often due to a lack of research funding, the existing centers for Holocaust studies were and largely have remained oriented towards educational and awareness-raising tasks – and hence, they are not able to engage in serious research. As a result, there was an almost complete absence of scholarly surveys on the Holocaust in Ukraine. In the meantime, using my experience, knowledge and documents I accumulated in the 1970s and the 1980s, I wrote the first general monograph, The Holocaust in Ukraine, 1941-1944 (Холокост на Украине 1941-1944 гг. Монография) and deposited the typescript in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

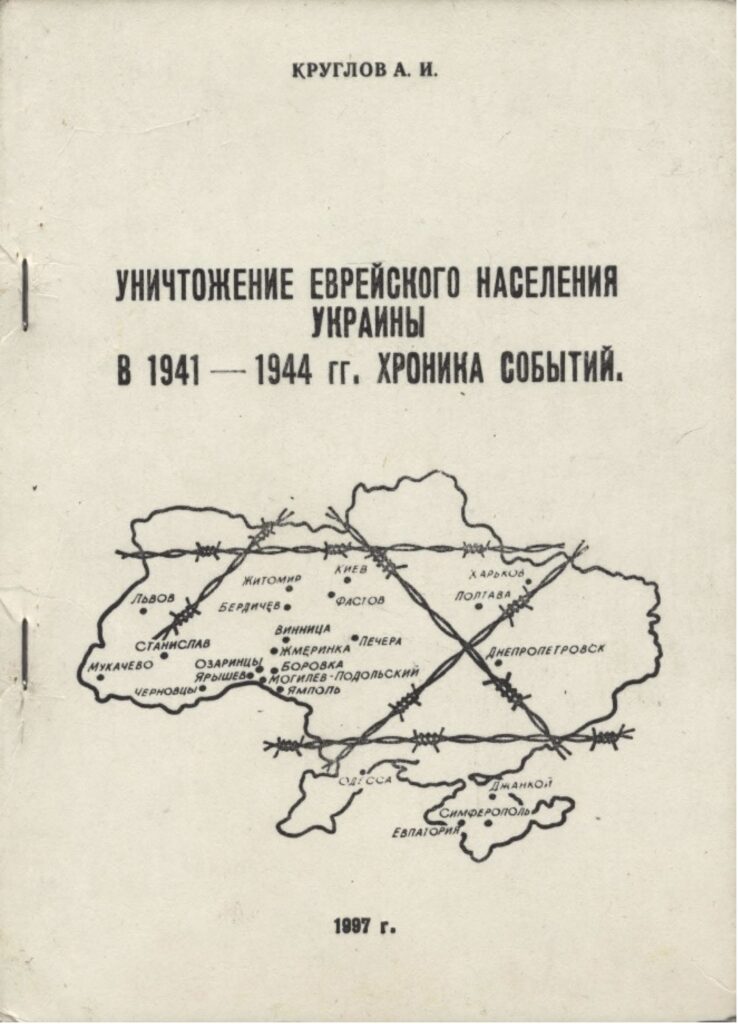

In 1997, I published a small monograph entitled The Extermination of the Jewish Population of Ukraine in 1941-1944: A Chronicle of Events. A revised and expanded edition of the chronicle appeared in Dnipro in 2004 (Хроника Холокоста в Украине).

In 2005, I published in Kharkiv a monograph on Ukraine’s Jewish losses, in Russian (Потери евреев Украины в 1941-1944 гг.). The English translation, The Losses suffered by Ukrainian Jews in 1941-1944, also appeared.

Publishing documents

In the 1990s and 2000s, I also published several collections of documents on the Holocaust in Ukraine. The first appeared in 1995 in Kharkiv and was entitled The Jewish Genocide in Ukraine during the Occupation in German Documents, 1941-1944 (Еврейский геноцид на Украине в период оккупации в немецкой документалистике 1941-1944). In 2002, the Institute of Judaica in Kyiv published the significantly larger Collection of Documents and Materials on the Extermination of Ukrainian Jews by the Nazis (Сборник документов и материалов об уничтожении нацистами евреев Украины в 1941-1944 годах). These books included little known, or entirely unknown Soviet documents, and especially German documents that I translated into Russian. Some of these German documents I had identified in Soviet and post-Soviet archives. Others, as I indicated above, I had received from German law enforcement agencies.

Colleagues and archives abroad: assistance and visits to Germany, France and Israel

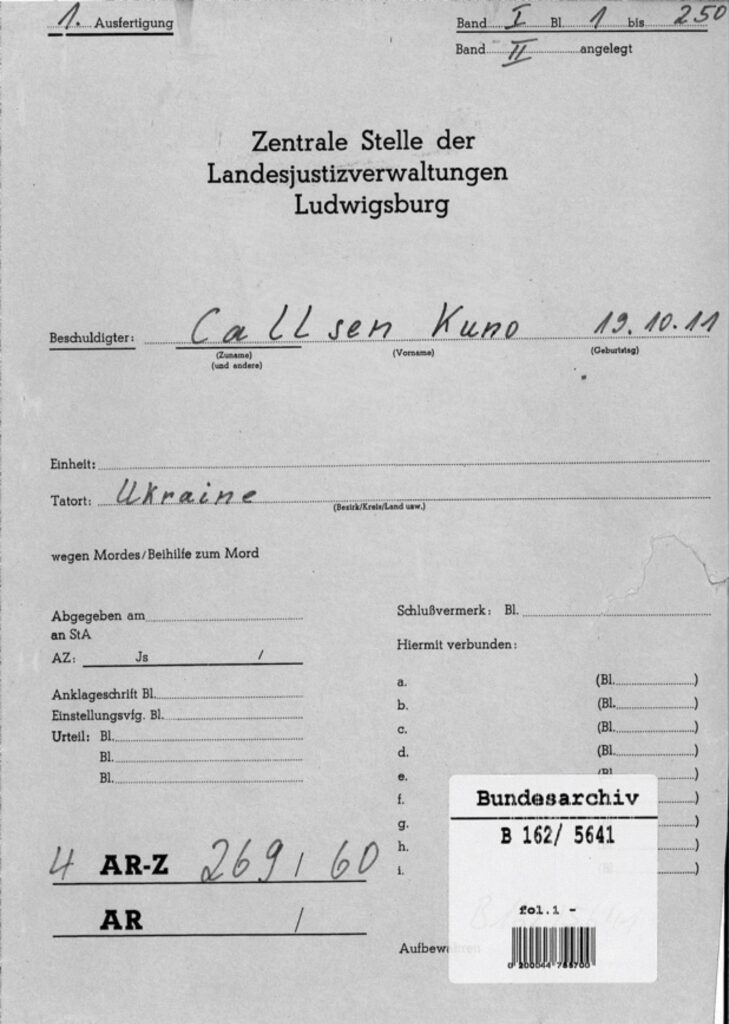

I was greatly assisted in obtaining German documents on the Holocaust in the USSR by Dr. Andrej Umansky, now a lawyer in Cologne, Germany and a member of the board of directors of the international association Yahad-In Unum (Paris, France), which works to identify sites of mass shootings of Jews and Roma in Eastern Europe during World War II (and also to fight antisemitism and improve Catholic-Jewish relations). These documents were mainly from the branch of the German Federal Archives in Ludwigsburg11, and they were investigative cases (often comprising many volumes) against Nazi criminals. I also managed to visit Ludwigsburg myself and copy investigation files.

For my articles, monographs and collections of documents I also used eyewitness testimonies collected by Yahad-In Unum’s interview teams, held in the Yahad-In Unum archive12 (in 2016), as well as documents I had seen during visits to the archive of the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich and at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem (in 2015 and 2018-2019, respectively).

Collaboration with the USHMM and the Holocaust Center in Moscow

I collaborated with the USHMM for a long time, from 2005 to 2018. Martin Dean, the Applied Research Scholar who recruited me, was one of the editors of the second volume of USHMM’s multi-volume Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945.13 The second, third and fourth volumes of this Encyclopedia published 475, 23, and 404 articles of mine, respectively. Some of these were co-authored with Dr. Dean, about ghettos and camps in Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Poland. Using my extensive knowledge of the Holocaust in the USSR and the extensive documentation and literature I had collected, I wrote the articles in Russian. They were then translated into English by USHMM. For nine months between 2013 and 2014, I was the J.B. and Maurice C. Shapiro Senior Scholar-in-Residence Fellow at the Museum’s Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies.

I also contributed 217 entries on the Holocaust in selected localities of the former Soviet Union to an encyclopedia edited by Ilya Altman entitled The Holocaust in the Territory of the USSR (Холокост на территории СССР: Энциклопедия), published in 2009 in Russian by the Research and Educational Holocaust Center in Moscow. Although I provided all these articles with a scholarly apparatus, they were published without it, which of course had a negative impact on the general scholarly level of this Russian encyclopedia.

More recent publications

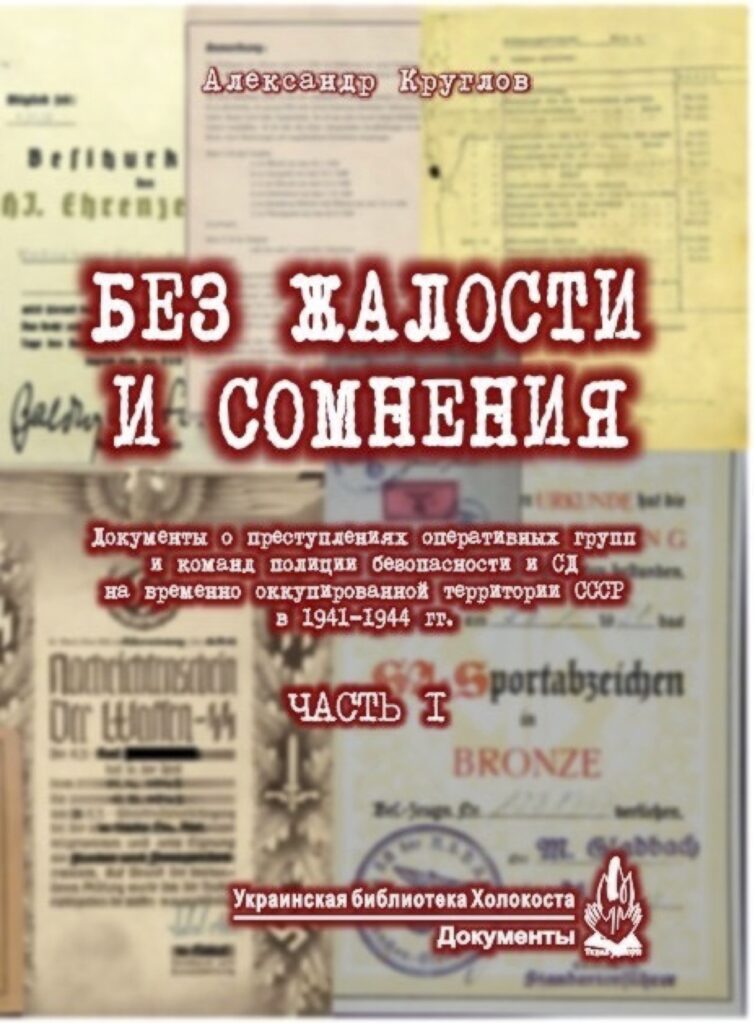

I would like to highlight the four volumes with documents that I prepared for publication in recent years. The set, entitled Without Pity and Doubt, was published between 2008 and 2010 by the Tkuma Center and contains documents on the crimes of the Einsatzgruppen and Einsatzkommandos of the Security Police and the SD in the occupied Soviet territories (Без жалости и сомнения. Документы о преступлениях оперативных групп и команд полиции безопасности и СД на временно оккупированной территории СССР в 1941—1944 гг.).14

Most recently, in 2016-2017, a two-volume collective monograph was published in Dnipro, in Russian entitled The Holocaust in Ukraine, which was coauthored with Andrej Umansky and Ihor Shchupak. It summarizes recent research on the topic.15

From 2017 onwards, I participated in the scholarly work of the new NGO Babyn Holocaust Memorial Center, particularly for the Basic Historical Narrative16, the names of German perpetrators, and geolocation of the Babyn Yar ravine.

Looking ahead

In conclusion, a few words about the prospects of Holocaust studies in Ukraine. These prospects do not seem very bright to me. Firstly, because Ukrainian historians who write about the Holocaust do not research the topic on a regular basis, but occasionally, casually or for opportunistic reasons. Many of them do not know German (a knowledge of which is indispensable, since a vast array of documents are in that language) and have no access to foreign archives. They are fragmented and are not aware of who is doing what in the field.

The two institutes for Holocaust studies in Ukraine (in Kyiv and Dnipro) could coordinate scholarly research, but they have no appropriate scholarly staff and adequate funding. They compete with each other and they focus on teaching and educational tasks. The Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine also has no desire (or possibility) to coordinate Holocaust studies.

The situation could be remedied by the establishment, for example, of an International Center for Holocaust Research in Ukraine (or more broadly in the former USSR). Such a center would unite Ukrainian and foreign historians and coordinate their work.17 No foreign scholary organization engaged in Holocaust studies has yet come up with such an initiative.

It is hardly possible to create such a center in Ukraine itself, especially taking into account the aggression of Putin’s Russia against my country. Maybe EHRI should investigate this issue and initiate the establishment of such a Center.

Translated from the Russian by Karel Berkhoff

- Документы обвиняют. Сборник документов о чудовищных преступлениях немецко-фашистских захватчиков на советской территории / Чрезвычайная государственная комиссия по установлению и расследованию злодеяний немецко-фашистских захватчиков и их сообщников. Выпуск II (Москва: Огиз/Госполитиздат, 1945); available online at https://nibu.kyiv.ua/greenstone/cgi-bin/library.cgi?e=d-01000-00—off-0adminZz-19411945–00-1—-0-10-0—0—0direct-10—4——-0-1l–11-uk-50—20-about—00-3-1-00-0–4–0–0-0-11-10-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=admin-19411945&cl=CL2&d=HASH01a9ff7f07cf1a90c68af702 and at http://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/167161-dokumenty-obvinyayut-sbornik-dokumentov-o-chudovischnyh-zverstvah-germanskih-vlastey-na-vremenno-zahvachennyh-imi-sovetskih-territoriyah ↩

- On the ChGK, see https://blog.ehri-project.eu/2020/09/28/connecting-extraordinary-state-commission/ ↩

- Зверства немецко-фашистских захватчиков. Документы. Выпуск 1-15 (Москва: Воениздат НКО СССР, 1942-1945). All but volumes 1 and 3 are available at http://resource.history.org.ua/cgi-bin/eiu/history.exe?&I21DBN=ELIB&P21DBN=ELIB&S21STN=1&S21REF=10&S21FMT=elib_all&C21COM=S&S21CNR=20&S21P01=0&S21P02=0&S21P03=ID=&S21COLORTERMS=0&S21STR=0010435 ↩

- https://portal.ehri-project.eu/units/ru-003205-r_7021 See also https://portal.ehri-project.eu/authorities/ehri_cb-001546 ↩

- For the former KGB archives, now held by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), the EHRI Portal listed first only the central repository in Kyiv (https://portal.ehri-project.eu/institutions/ua-003309 ); but in May 2022 work began to expand the coverage with the regional SBU archives. ↩

- Alexander Kruglow, “Die Deportation deutscher Bürger jüdischer Herkunft durch die Faschisten nach dem Osten 1940 bis 1945”, Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft ((East) Berlin), 32, no. 12 (1984), pp. 1084–1091. ↩

- Aleksander Krugłow, “Deportacja ludności żydowskiej z dystryktu Galicja do obozu zagłady w Bełżcu w 1942 r.”, Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego w Polsce, no. 3(151) (Warsaw, July-September 1989), pp. 101-118; online at https://cbj.jhi.pl/documents/788104/2/ ↩

- О.Й. Круглов, “Знищення фашистами іноземних громадян на окупованій територіï Украïни (1941-1944 рр.)”, Украïнський історичний журнал, no. 5(338) (Kyiv, May 1989), pp. 82-87, ; online at http://resource.history.org.ua/cgi-bin/eiu/history.exe?&I21DBN=EJRN&P21DBN=EJRN&S21STN=1&S21REF=10&S21FMT=njuu_all&C21COM=S&S21CNR=20&S21P01=0&S21P02=0&S21COLORTERMS=0&S21P03=I=&S21STR=journal/1989/5 ↩

- https://tkuma.dp.ua/ua/ ↩

- https://www.holocaust.kiev.ua/ ↩

- See https://portal.ehri-project.eu/institutions/de-006145 ↩

- https://portal.ehri-project.eu/institutions/fr-006167. There are copies at USHMM: https://portal.ehri-project.eu/units/us-005578-irn38217 ↩

- https://www.ushmm.org/research/publications/encyclopedia-camps-ghettos ↩

- The four are listed here: http://www.tkuma.dp.ua/index.php/ua/publikacy-tkuma/nauchnie-izdaniya/18-nauchnye-izdaniya/25-bez-zhalosti-i-somneniya-dokumenty-o-prestupleniyakh-operativnykh-grupp-i-komand-politsii-bezopasnosti-i-sd-na-vremenno-okkupirovannoj-territorii-sssr-v-1941-1944-gg-chast-1-4 ↩

- Холокост в Украине. Рейхскомиссариат “Украина”, Губернаторство “Транснистрия” (2016; online at http://irbis-nbuv.gov.ua/ulib/item/ukr0000014805 ; and Холокост в Украине. Зона немецкой военной администрации. Румынская зона оккупации. Дистрикт “Галичина”. Закарпатье в составе Венгрии (1939-1944) (2017). ↩

- https://babynyar.org/en/historical-narrative (October 2018). ↩

- By foreign researchers of the Holocaust in the former USSR including Ukraine, I mean first of all Jean Ancel (1940-2008), Andrej Angrick, Yitzhak Arad (1926-2021), Karel Berkhoff, Martin Dean, Wendy Lower, Dieter Pohl and Andrej Umansky, whose publications on the subject may serve as examples for Ukrainian historians. ↩

Professor Joachim Whaley

Dear Dr Kruglov,

I was fascinated and deeply impressed by your account of your research. The reason why i looked you up is that you were recommended to me by Dr Karl Berkhoff as the best person to review an application for a Research fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. The topic of the research is ‘Soviet Investigations of the Nazi Occupation’.

Dr Berkhoff told me that there is no one who is better qualified in this area than you.

I have been unable to find your email address online. Could you please email me, so that i can explain more?

Best wishes,

Joachim Whaley