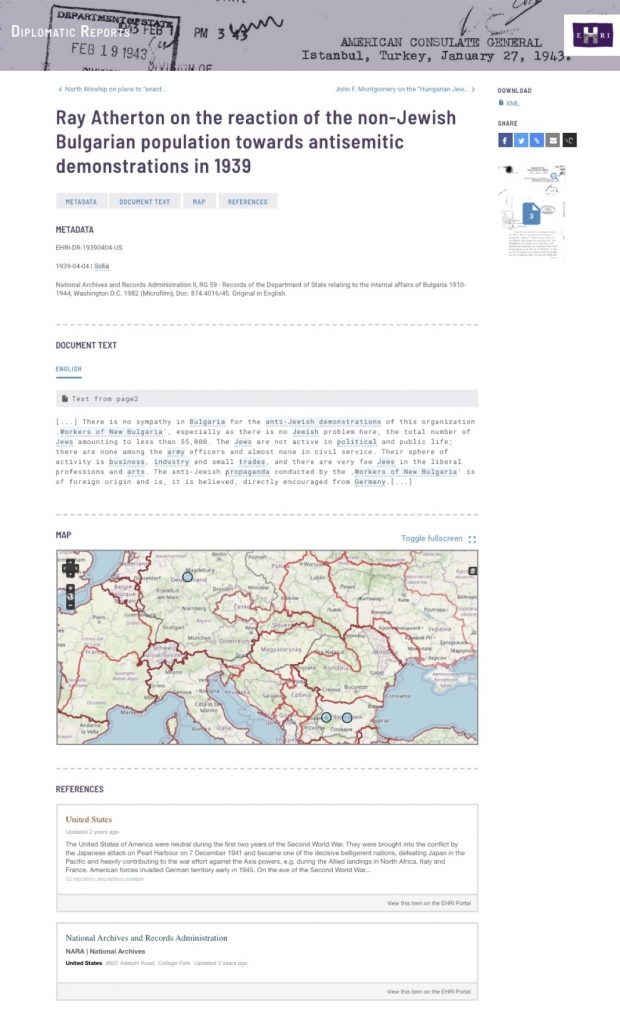

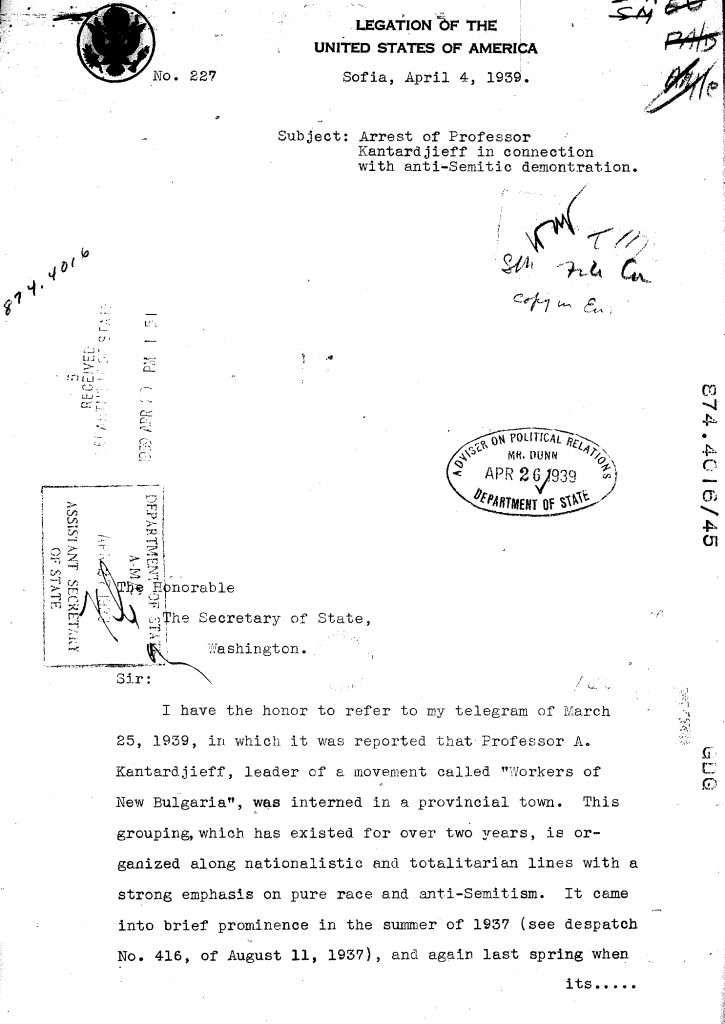

In April of 1939, the American diplomat Ray Atherton, stationed in Sofia, reported to the Secretary of State that “there is no sympathy in Bulgaria for the anti-Jewish demonstrations of this organization ‚Workers of New Bulgaria‘,” which “is of foreign origin and is, it is believed, directly encouraged from Germany”.1 This assumption was mirrored by the observations of Leland B. Morris, reporting in the summer of 1940 from Switzerland, on anti-Jewish measures in the German occupied territories, as well as in “Rumania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and unoccupied France”. He concluded that Germany must have “a definite program of carrying German anti-Semitism beyond the German borders into such countries as come into the German sphere of influence.”2

Today, the central facts of the unfolding of the Holocaust in Bulgaria are relatively well known. The “Law for the Protection of the Nation” came into effect in January 1941 and was followed by other anti-Jewish laws and decrees, culminating in the deportation of over 11.000 Jews from Bulgarian-occupied Macedonia, Thrace, and Pirot to Treblinka in 1943 – which less than 200 would survive. Eventually, the growing public, political and religious opposition and the course of the war prevented the deportation of Jews from core provinces and especially from the capital, Sofia.3

EHRI Online Edition on Diplomatic Reports

But what did contemporaries make out of these events, unfolding in front of them in real-time? A set of sources, which provides useful insights are reports written by diplomatic staff. Keeping their governments updated on the events taking place in the German occupied territories, they provide the reader with viewpoints from diplomatic staff of countries who were part of the Axis, the Allies or those countries who stayed neutral – or at least tried to. Currently, the EHRI Online Edition “Diplomatic Reports” makes available reports from the diplomatic staff of Denmark, Italy, Japan and the US. Hungary, Slovakia and Sweden will be added to the online edition shortly. The selected reports focus on how members of the diplomatic staff reported back to their superiors about the persecution and murder of Jewish men, women and children in the countries and regions occupied by Germany and its allies. The reports not only provide insights into the knowledge of contemporaries on these events, which would become to be known as the Holocaust, but how the authors themselves judged them and how they related the opinions of others. In addition, it also shows which aspects they identified as being particularly relevant in relation to their own country.

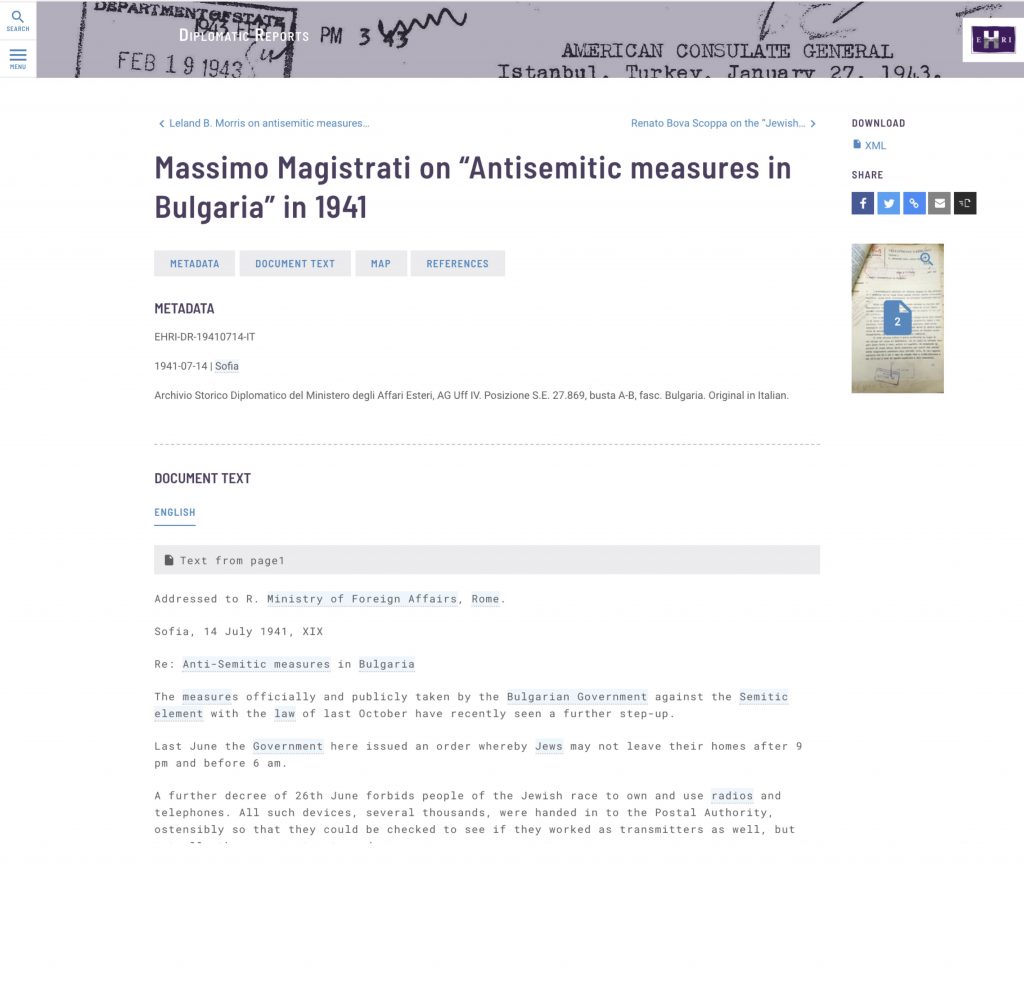

Therefore, diplomatic staff could come to very different conclusions and assessments when reporting on the same events. While George H. Earle III, who had succeeded Atherton as member of the US legation in Sofia observed, that “the Bulgarian people as a whole” reacted “apathetic […] and a little ashamed” towards the ‘Law for the Protection of the Nation’,4 Massimio Magistrati, the Italian envoy to Sofia, wondered if similar measures were planned in Italy, regarding “foreign Israelites”.5

Indeed, a complex picture emerges when viewing these events through the lenses of diplomats, reporting to their home countries on the developments in occupied Europe. As Frank Bajohr points out in his introduction to the edition,6 its special value for the historiography can be traced, at least in part, to the “hybrid position” of diplomats: they had access to influential personalities and decision-makers in their host countries, receiving insights often unachievable for people outside these orbits of power. At the same time, they often remained distant observers, who looked at the situation in these countries “through a foreign and, at times, ethnological lens”, rarely inserting themselves into the action.7

This does not mean, that individual characteristics, viewpoints and calls for action can’t be found in the reports. In a letter to the State Secretary, Burton Y. Berry, the consul to Istanbul, described his meeting with “a prominent non-Jewish member of the Bulgarian Parliament” in the spring of 1943. This member had informed him about the imminent threat of deportation that all Bulgarian Jews faced – and that due to protest by the public as well as prominent political and religious figures the order had, as of yet, not been carried out. Berry also related the hope of the parliamentarian, that the US would voice “a vigorous protest to the Bulgarian Government […] declaring in the strongest terms its abhorrence of the policy of the Bulgarian Government toward the Jews.” Though not offering an explicit opinion on the request, Burton lengthy underscored the parliamentarian’s plea and the presumed effect that such an intervention by the US would have, despite Bulgaria’s alliance with the Axis powers at that time.8 While numerous reports by diplomatic staff on the situation of Jews in Bulgaria pointed out the public and prominent protest against the deportations, only Yamaji Akira, the Japanese Consul General to Vienna, related in his reporting rumors “that the Jews spent a lot of money” on manipulating public opinion in their favor.9 However, it would be inaccurate and impossible to draw a concrete line between the way diplomats of the Allies and the Axis powers reported on the persecution of European Jewry. In May 1943, the Italian consul in Skopje, Roberto Venturini, described the deportation of Macedonian Jews to a transit camp in the city and closed his report with the observation “that there are very few people who […] have not felt a sense of pity for those thus stricken and of deep condemnation of the Bulgarian authorities responsible for this and for their agents.”10

In order to select and prepare these documents for publication, the EHRI partner Center for Holocaust-Studies at the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ) invited a group of local experts who selected the documents for the respective countries. The edition chooses a broad approach to Diplomatic Reports, including brief telegrams, thorough examinations or multi-perspective accounts written by diplomats, consuls and other staff members of the diplomatic service – many of these documents have not been previously published. Each set of diplomatic repots is prefaced by introductory remarks on the respective country with helpful information on the make-up of the diplomatic staff as well as the diplomatic relationship with Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, allowing for additional historical classification of the reports. All documents are available in English translation (including the English transcription of the American reports). For the majority of documents, it was possible to include a scan of the original document.

The annotation of documents consists primarily of tagging and linking words or expressions in the documents, using links to established controlled vocabularies11 (EHRI for Holocaust-related entities; Geonames for geographic information, online encyclopedias such as Wikipedia for biographical data on diplomats, etc.). For each document in the edition, the following features are displayed: Meta data, translated document text (scan of the original document), map with the borders of April 1939 and 1942 displaying the geographic entities named in the text and references to the EHRI Portal. Together with the search function, this allows users to put documents from various countries and delegations into different contexts and perspectives to allow comparative research as well as the study of the diplomatic reception of the persecution of Jews in individual countries.

The book Fremde Blicke auf das Dritte Reich (Foreign Views on the Third Reich), edited by Frank Bajohr and Christoph Strupp, had already brought together research on diplomatic staff stationed in Nazi Germany.12 The contributions to the book show, that many diplomats noted early on the specific quality of the national socialist’s radical antisemitism – a radicalism that likely would not be restricted to limiting legal statutes of the Jewish minority. Similarly, the reports in the EHRI Online Edition showcase the various ways, German authorities encouraged and pressured countries to concentrate and deport their Jewish population. In addition, it shows the varying degree of willful compliance, anticipatory obedience and – especially in the later stages of war – growing reluctance with which the countries reacted to the German demands.

Even more so, the documents gathered in the online edition make painfully clear how widespread the knowledge of the systematic persecution and deportation of Jewish women, children and men by German forces and their allies was. Returning to the example of Bulgaria, the consul general from the US in Istanbul, Samuel W. Honaker, related in his report in November 1942 various opinions and rumors on the dire fate of the Bulgarian Jews: “They are supposed to be deported to towns and villages in Bulgaria but some high placed persons believe many of them will be deported to Poland. Some think they will be put in concentration camps inside of Bulgaria where many will eventually die of disease and starvation. Others, including the surgeon referred to above, think that a large proportion of them will be shot, as they have been in Belgrade and other cities. In any case, the content of the law, together with the severity with which it is being enforced show that its purpose is the complete destruction of the Jewish community in Sofia.”13 Only a couple months later, in March of 1943, Burton Y. Berry confirmed that the actions of the Bulgarian government became clearly “directed towards elimination of the Jewish population […] Liquidation is now being ruthlessly carried out in annexed territories where Jewish deportees are shipped in open freight cars to concentration camps.”14 Though the reports do not mention the systematic murder by shooting and gassing, they do describe, partly in great detail, concrete actions and pogroms, for example in Romania,15 or the destruction of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki.16

The merit of the EHRI Online Edition Diplomatic Reports not only lies in making these often unpublished reports widely available. Thanks to the technical implementation and editorial standards, the online edition allows to gather information on specific regions and events, opening new possibilities to compare the reporting from the various delegations and opens up new lines of inquiries towards this unique – and oftentimes underused – set of sources.17

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19390404-US ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19401105-US ↩

- See: Susanne Heim et.al. (eds.), Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933–1945, Band 13: Slowakai, Rumänian, Bulgarien, Berlin 2018, p. 74-92; Bulgaria in: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/bulgaria. ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19430601-US ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19410714-IT ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/exhibits/show/about/introduction ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/exhibits/show/about/introduction ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19430325-US ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19430529-JP ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19430316-IT ↩

- https://portal.ehri-project.eu/vocabularies/ehri_terms ↩

- Frank Bajohr/Christoph Strupp (eds.), Fremde Blicke auf das „Dritte Reich“. Berichte ausländischer Diplomaten über Herrschaft und Gesellschaft in Deutschland 1933-1945, Göttingen 2011. ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19421116-US ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19430323-US ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19410130-US and https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19411104a-US and https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19420923-IT ↩

- https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19430811-IT and https://diplomatic-reports.ehri-project.eu/document/EHRI-DR-19430320-IT ↩

- https://documentation.ehri-project.eu/en/latest/editions/index.html ↩