During the death march in 1945, Nena Szlezynger, a Polish-Jewish seventeen-year-old girl, was marching with the inmates of a Silesian labour camp in Neusalz an der Oder towards Dresden. She was wearing a blue winter coat with a fur collar, a valued possession she had been able to keep for over two years after being deported from Warthenau ghetto. The coat had been made in Helsinki by her uncle Bernhard Blaugrund’s firm and it had been sent to her to the ghetto in 1942. The march took place in freezing cold weather and clothing was a matter of life and death. Besides, with a neat coat, one stood better chances begging locals for food.

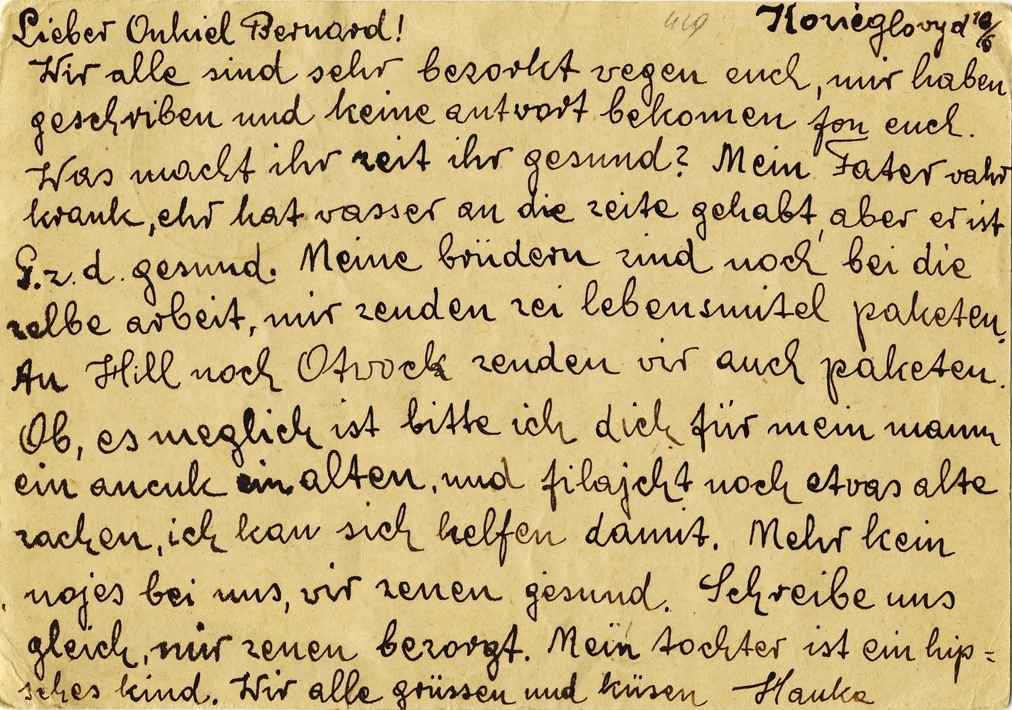

Image 1: Jakób Blaugrund’s open letter, sent 9 December 1940 from the Litzmannstadt ghetto to his brother Bernhard Blaugrund in Helsinki. The card bares the German and Finnish censorship stamps. The stamp of the Litzmannstadt ghetto in the left-hand corner states that the letter is sent under the auspices of the Eldest of the Ghetto, Chaim Rumkowski. The stamp in the top middle indicates that, besides postage, Jakób had to donate money towards the ‘winter relief for the German nation’. (Courtesy of Nena Kafka, Helsinki.)

Letters sent from the ghettos of Nazi-occupied Poland to Axis-allied Finland reveal that during the Holocaust, Jewish families in Finland engaged in private parcel campaigns in order to help their relatives. In some cases, like the Blaugrund family, these campaigns developed into wide networks, through which aid was further distributed to people in concentration camps and in hiding. Despite censorship, the families could discuss parcels, money and their distribution among relatives quite openly. The discovery of such correspondences in some family archives in Finland sheds new light on the history of the Holocaust.

The Finnish Jewish community, which was about 2 000 members strong, was in a peculiar situation in a country that was co-belligerent with Nazi Germany between 1941-1944. Jews themselves became the brothers-in-arms of their worst enemies. However, there were no antisemitic laws in Finland and Jews were able to continue living their lives as other Finnish citizens. This enabled some of them, despite a huge shortage of food and heavy rationing, to assist their more gravely suffering loved ones in occupied Poland and Lithuania.

Sending parcels to relatives and acquaintances was a private initiative among Finnish Jews, unlike the neighbouring Sweden, where Jewish communities and aid organisations launched wide public parcel campaigns to Nazi Germany and occupied countries. The only public campaigns and collections among Finnish Jews were aimed at supporting the Jewish refugees, who had settled in the country before the war, and families and widows of fallen Finnish-Jewish soldiers. Until now, the private parcel campaigns among Finnish Jews have been unknown. The discovery of the letters contests common beliefs in Finland that the Jewish community was so detached from the Nazi occupied zones as to be completely unaware of the ongoing genocide.

The main challenge for research is the fragmentary nature of the correspondences. It appears that many letters never made it through censorship or reached their destination. This becomes clear from the numerous inquiries about whether letters had been received or why no answers had arrived. Also, not all letters received in Finland were saved after the war and, understandably, no letters sent to the ghettos have survived. In the Blaugrund case, some of the letters sent from the ghettos were given to two surviving relatives as mementos of their perished families, while the rest have gone missing. A post-war Yiddish article in the Yedies of the Swedish Section of the Word Jewish Congress reports that documents concerning Finnish Jewish aid for Polish Jews were sent to the YIVO Archives in New York but, despite several attempts, I have not been able to locate them.1 Nevertheless, the surviving couple of dozen letters give an inkling of the nature and scope of the relief activity.

In what follows, I will give an overview of the private parcel campaigns of the Blaugrund family. I will also refer to interviews I conducted with the senders and the recipients in the family between 2008 and 2013.2 I will discuss the impact that the used clothes, money and food that were sent had on the lives of the recipients. This micro-historical approach speaks to wider issues about Jewish self-help during the Holocaust and how communities and individuals found ways to assist their coreligionists.

Parcels of used clothes

Polish-born Bernhard Blaugrund (1889-1948) settled in Helsinki during the First World War but kept close contact with his mother and seven siblings in Poland, frequently visiting them. Blaugrund established a fabric wholesale business in Helsinki and became one of the wealthiest merchants in the Jewish community. He was already known for his philanthropy before the war and was the first chair of the Jewish Refugee Committee established by Helsinki’s Jewish Community in 1938. When the Second World War broke out, none of his close family members managed to flee Poland.

The members of the Blaugrund family soon ended up in various ghettos in the General Government and areas annexed to the Reich. Bernhard kept in touch with them through ‘open letters’ or postcards that ghetto inmates were allowed to send. The postcards, which had to be written either in German or Polish, were subject to heavy censorship, both German and Finnish. The ghetto inmates were instructed on what the letters could contain. Primarily, they were not to include any compromising or strategic information.

After the outbreak of the war, Bernhard started receiving requests from his relatives for material help. Used clothes were among the only things one could send out from Finland during the war. Practically everything in the country was rationed and sending food, medicine and new clothes was prohibited under a strict export ban. The letters would contain phrases like: ‘if you can, be kind and send me something, it could be clothes’, ‘if you have a possibility to send me an old men’s suit, I would be very grateful’, ‘if it is possible, I ask, could you send my husband an old suit, and maybe also some other old things that I can use to ease my situation’. Clothes were a valuable asset in the ghettos. According to historian Pontus Rudberg, who has studied the Swedish parcel campaigns, one Swedish aid worker claimed that clothes had ‘greater value than money’ in Poland.3 They could be traded for other goods that the inmates needed.

Besides sending readily available used clothes, Bernhard, who was in the fabric production and retail business, had new clothes made. His relatives and acquaintances in Helsinki would wear them for a while so that they could pass as used items in customs. Bernhard’s daughter Hanna Eckert (1924-2013) told me she even remembers wearing brand new shoes, a rare commodity in wartime Finland, to be sent to relatives in the ghettos.

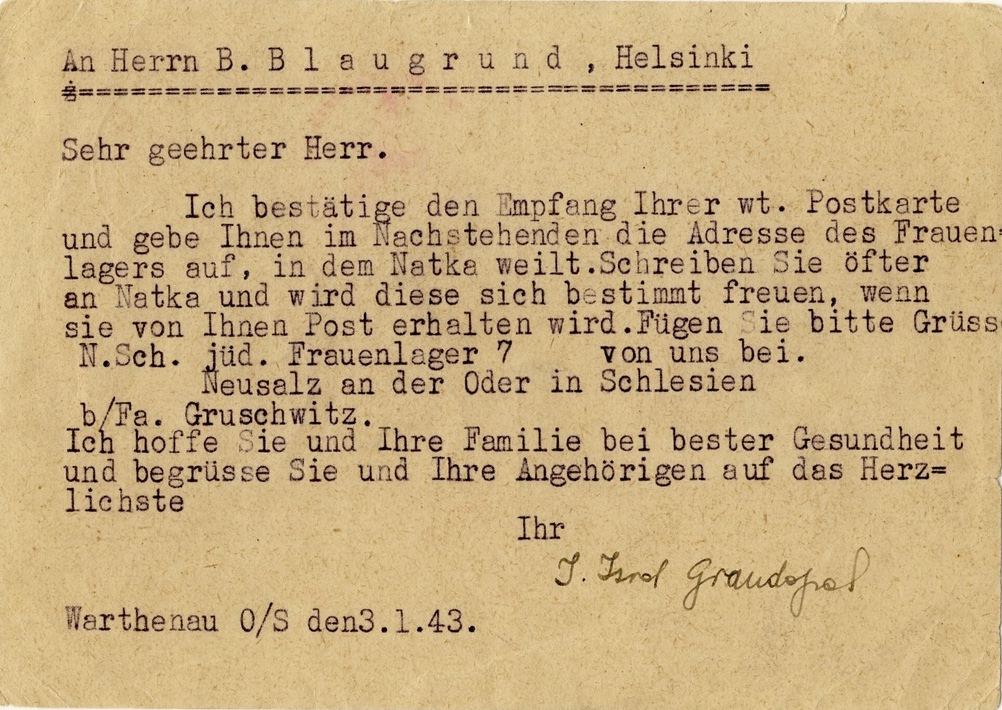

The clothes were sometimes sent further from the ghettos to concentration camps. In October 1940, Bernhard’s niece Hanka Szlezynger (1912-1942) wrote from an open ghetto in Kozieglovy (Polish, Koziegłowy), in the south-western part of Poland annexed to the Reich: ‘My brothers and my husband need clothes, maybe you could send them men’s clothes, hats and shoes’. Hanka’s two brothers Szmul and Benjamin and her spouse Lejb had been sent with other men from the area to labour camps in Germany. In another letter dated 10 June 1941, she explains how she is also sending them foodstuff to the camp. She does not use the word concentration or labour camp but just refers to ‘work’ (see image 2).

Image 2: Hanka Szlezynger’s open letter, dated 10 June 1941 in Kozieglovy, to her uncle Bernhard Blaugrund in Helsinki. The letter is written in Yiddish-influenced German, partly with Polish orthography. Writing in Yiddish with Hebrew characters was forbidden. (Courtesy of Nena Kafka, Helsinki.)

Image 3: Hanka Szlezynger with her daughter Lusia in a photo sent to Helsinki. Hanka wrote on the back: ‘For my loved ones! As a memento, Hanka and Lusia, Kozieglovy 10.6.1942’. A couple of days later, all the Jews from Kozieglovy were deported to Warthenau for a selection and from there, mothers with small children and the elderly to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Even though there are only a couple of dozen letters available, their content indicates that the correspondence was frequent and wide spanning, including more distant relatives and acquaintances in the ghettos of Warsaw and Koluszki. The letters sent to Helsinki make clear that family members in various ghettos were also corresponding among themselves, and occasionally someone in a ghetto would ask the Helsinki relatives if they had heard from relatives in another ghetto. Ghettos occasionally issued temporary bans on correspondence and many letters apparently went missing.

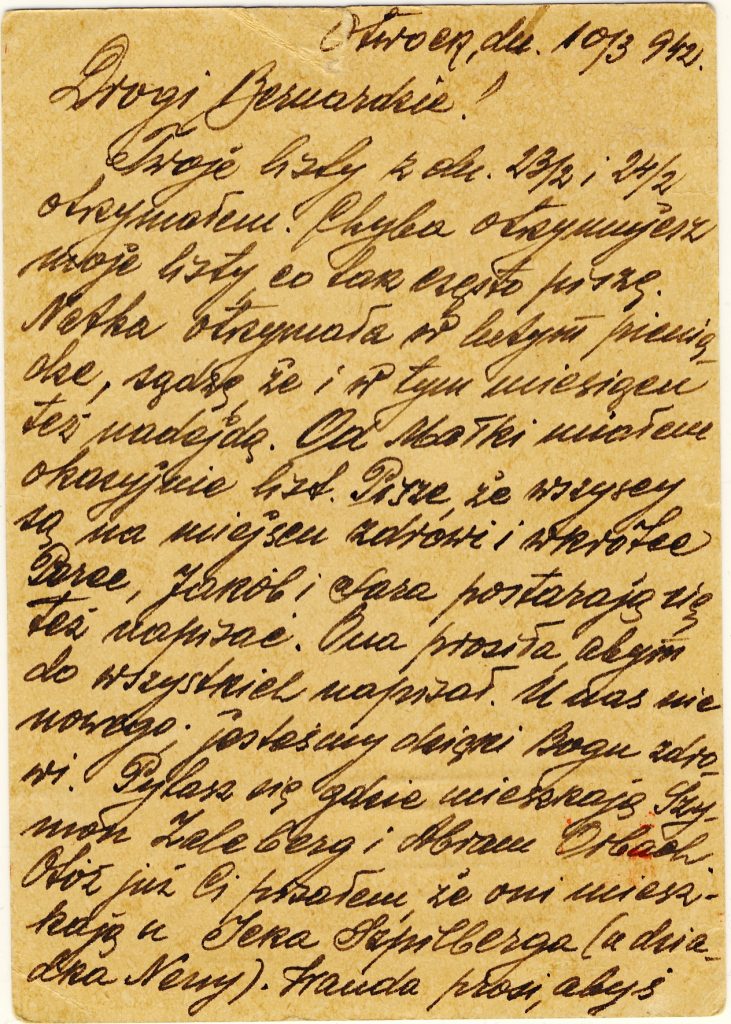

Towards the end of 1942 it became increasingly difficult to receive parcels. Bernhard’s niece Nena Szlezynger (b. 1927) had been receiving parcels, including the aforementioned blue winter jacket, in the Warthenau (Polish, Zawiercie) ghetto to which she had been transferred after the liquation of the Jewish community of her hometown Kozieglovy. Then, one day, she got a notification of the arrival of a parcel containing old clothes that she was not allowed to receive. According to Rudberg, a member of the Swedish relief committee was informed in November 1942 that their shipments to the General Government had been rerouted and it was possible to communicate only with the Jewish Aid Agency (Jüdische Unterstützungsstelle) in Cracow. From this point on it became practically impossible to send aid to individuals. By then, most of Bernhard’s relatives had been deported from the ghettos anyway, and they were either in labour camps or had been murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau and Treblinka. On 3 January 1943, Bernhard received the address of the labour camp to which his niece Nena had been sent, but none of his letters or postcards reached her (see image 4).

Image 4: I. Isrol Grandapel’s open letter, dated 3 January 1943 in Wathenau ghetto, to Bernhard Blaugrund in Helsinki. The letter gives the exact address of the labour camp in which his niece Nena has been placed. (Courtesy of Nena Kafka, Helsinki.)

It appears that after January 1943, the only person Bernhard was able to send parcels to was his brother Hilary’s (1895-1942) wife Blanka. Along with their son Abraham, she had escaped the Otwock ghetto before its liquidation in August 1942 and went into hiding in Warsaw with the assistance of her Polish friends. Blanka contacted Bernhard under the false identity of ‘Stanisława Sadowska’ and asked for help. Bernhard started to send her parcels using a non-Jewish name of his own. Abraham Blaugrund (1930-2019) told me that the used clothes they received from Helsinki were vital for their survival in hiding, especially to pay off szmalcowniks, who knew of their whereabouts and were blackmailing Blanka.

Financial support

Berhard Blaugrund was also able to send money to his relatives. In order to get foreign currency, he needed to obtain a permission from the Finnish authorities. He sent cheques to his sister Nena Frymeta Unger (1900-1943), who lived with her husband Heniek and their two children Hanka and Hilek in the area designated for Jews in Sosnowitz (Polish, Sosnowiec) that had been annexed to the German Reich. The cheques in Reichsmarks for ‘Nena Sara Unger’ were ordered from the Deutsche Bank in Berlin through the Helsinki branch of the Nordiska Föreningsbanken (Nordic union bank). When a cheque arrived in Helsinki, it was sent by post to Sosnowitz.

Correspondence between the Blaugrund family members shows that the money orders were discussed across the border of the General Government and the Reich. In March 1942, Bernhard’s brother Hilary in the Otwock Ghetto wrote to his brother in Helsinki that Nena Frymeta in Sosnowitz had received the money sent in February and that they were hoping the next cheque would also go through (see image 5). The money sent to the Reich was most likely spent on the commodities distributed among family members also in the ghettos of General Government.

Image 5: Hilary Blaugrund’s open letter in Polish, dated 10 March 1942 in Otwock ghetto, to his brother Bernhard Blaugrund in Helsinki. The letter discusses the money sent to Sosnowitz and the fate of some individuals. (Courtesy of Nena Kafka, Helsinki.)

Owing to the censorship, code had to be developed to conceal compromising information that would obstruct the letter going through. In the above-mentioned letter by Hilary to Bernhard, Hilary answers Bernhard’s question about two individuals that ‘they are with Icek Szpilberg (Nena’s grandfather)’ most likely a code for them being deceased. Icek Szpilberg was the grandfather of the Blaugrund siblings, who had died long before the war and was buried in the Lodz Jewish cemetery.

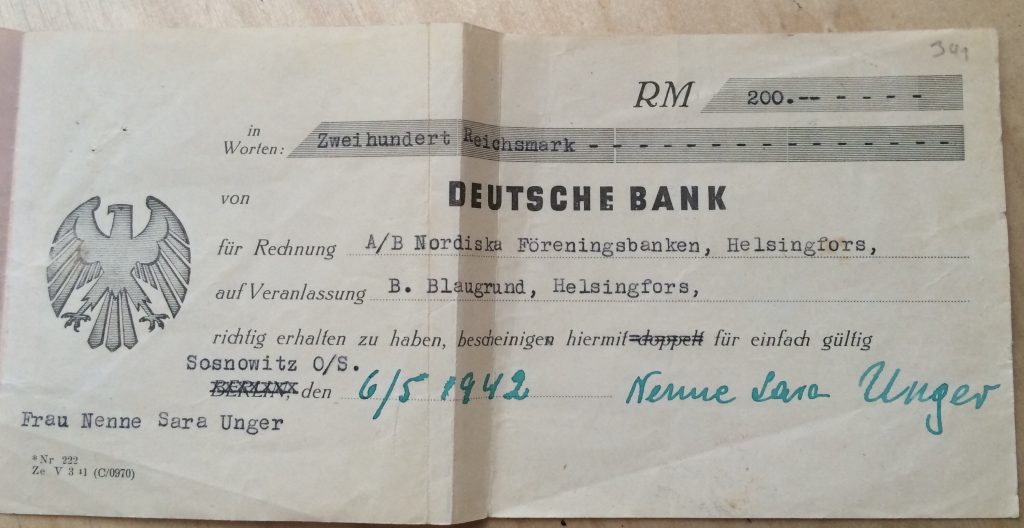

By the end of 1942, sending money to the Reich became impossible. On 26 November 1942, Bernhard Blaugrund received a letter from his sister Nena Frymeta asking him not to send cheques anymore. As with the parcels, it was no longer possible to receive them and the cheques would be returned to the sender. There is one such returned cheque, dated May 5, 1942, for 200 Reichsmarks (see image 6). In the above letter, Nena Frymeta’s husband Heniek adds: ‘I have written twice already that you should not send money to your sister, because she does not need it. You can cancel the money you have already sent. We don’t need anything … ’. Only a month later Nena Frymeta, Heniek and their children were transferred to a closed ghetto in the Środula district of Sosnowitz and soon thereafter, Heniek was deported to the Gleiwitz II labour camp.

Image 6: Bernhard Blaugrund’s cheque, issued 6 May 1942 in Helsinki, for his sister Nena Frymeta Unger living in Sosnowitz. According to the Nazi regulations in Germany, the name Sara was added to Nena’s name. (Courtesy of heirs of Anna and Abraham Baran.)

Food parcels through RELICO

Correspondence found in the World Jewish Congress files at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem give us further information about the relief activities of the Blaugrund family. While it was not possible to send food from Finland, Bernhard Blaugrund found a way to go round this. He heard that one could get food to the ghettos through RELICO, the Relief Committee for the Warstricken Jewish Population. RELICO was founded in Geneva in 1939 and was largely funded by the World Jewish Congress. Bernhard would have probably heard about this possibility from his Swedish acquaintances or his brother-in-law who lived in Sweden. According to Rudberg, Swedish aid organisations were using RELICO to send thousands of food parcels to German occupied Europe. RELICO, which had good contacts with the Red Cross, diplomats and the Catholic and Protestant churches, used Portuguese shipping firms.

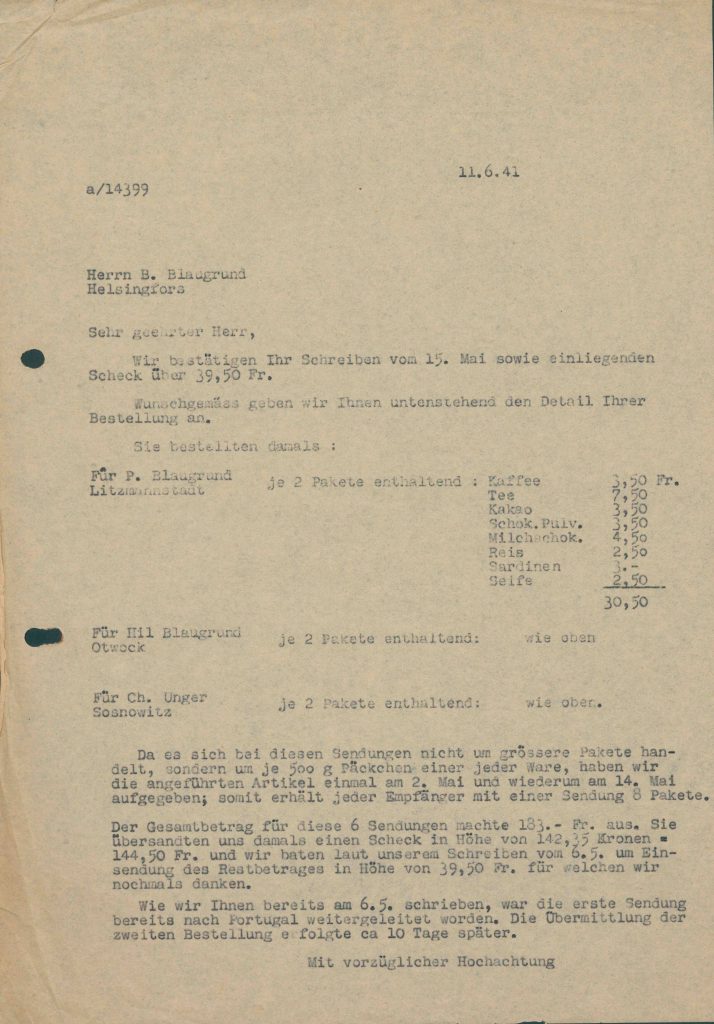

During spring and summer 1941, Bernhard corresponded with RELICO and ordered food parcels to be sent to his brother Perec (1892-1964) in the Litzmannstadt (Polish, Łódź) ghetto, his sister Nena Frymeta in Sosnowitz and his brother Hilary in the Otwock ghetto. On 11 June 1941, Bernhard received confirmation from RELICO that his siblings had been sent two 500 grams parcels each during May of that year (see image 7). The parcels contained coffee, tea, cacao, dark cacao, milk chocolate, rice, sardines and soap.

Image 7: Image 7: RELICOS’s letter, date 11 June 1941, to Bernhard Blaugrund, confirming the shipment of food products to his sister in Sosnowitz and two brothers in the ghettos in Otwock and Litzmannstadt. (C3\1117-3, Office of the World Jewish Congress in Geneva, Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem ).

The extent of Bernhard’s activity sending food parcels through RELICO and his relatives receiving the parcels, remains unknown. It was, at any rate, a time consuming and slow way to send relief because it involved ordering currency and writing several letters to Switzerland.

Conclusions

Only five of Bernhard Blaugrund’s twenty-three close family members in occupied Poland survived the Holocaust. His niece Nena Szlezynger was one of them, surviving the death march and the Flossenbürg and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. She came to Finland via Sweden to live with her uncle Bernhard in August 1945. She soon started working in her aunt Vera’s drapery shop in the centre of Helsinki. One day, when working there, she was shocked and pleased to recognise the blue fabric used for the coat she had received in the Warthenau ghetto, and which she last wore during the death march.

Though minor in scale, the private parcel campaign of Bernhard Blaugrund had a huge impact on the lives of his family members in ghettos, labour camps and in hiding. Besides, establishing a tangible connection to these families and raising their morals, the packages brought relief to their daily struggle in the dire conditions and in some cases, contributed to their survival.

I would like to thank Nena Kafka and the heirs of Anna and Abraham Baran for giving their permission to publish documents from their archives, and the Central Zionist Archives for granting permission to publish a document from their collections. I would also like to thank Pontus Rudberg for his information concerning Swedish relief activities.

- Material-zamlungen farn ‘YIVO’ fun Danmark un Finland”, Yedies (aroysgegebn funem yidishn veltkongres), 5 Nov 1948. ↩

- Hanna Eckert’s (nee Blaugrund) interview in 2011 in Turku, Finland; Abraham Blaugrund’s interview in 2014 in Rehovot, Israel; Nena Kafka’s (nee Szlezynger) interview in Helsinki in 2011. ↩

- Pontus Rudberg, ‘An undeniable duty. Swedish Jewish Humanitarian Aid to Jews in Nazi Germany during the Second World War’. Paper presented at the conference Lesson and Legacies of the Holocaust, November 2018 in St Louis. ↩

Galit Hasan-Rokem

Thank you Dr. Simo Muir for this moving and informative research about the desperate efforts of my maternal grandfather to help his relatives to survive in an impossible situation. I believe that his premature death at the age of 59 was probably hastened by the fact that so few of them survived. The survivors in our family, as well as other survivors who had been able to settle in Fnland were both intimately and strikingly present in our home in my childhood years.

Sincerely, Galit Hasan-Rokem

Gitta Blaugrund Dicks

Kiitos

Bernhard Blaugrundin lapsenlapsi

Gitta

Teri Dobbs

Dear Simo–

Bravo! I appreciate your meticulous research and the resulting narrative that illuminates yet another critical part of the Shoah. Thank you!

Sincerely,

Teri Dobbs, University of Wisconsin-Madison

RUTH APTER -GABRIEL

Many thanks, Dr. Simo Muir for all the interesting work you have exhibited as well as

published on the history and fate of the Jewish Community in Finland.

Ruth Apter-Gabriel

Jerusalem (formerly Helsinki)

Prempain, Laurence

Dear Simo,

Thanks to your work, not only Nena’s story but all her members’ family emerge from oblivion. You gave them back their identity, this is of great Value.

Laurence

Yale Strom

Wonderful article Simo. It just goes to show that nothing was completely black or white when it comes to the daily situations Jews found themselves in during their time in the ghettos and various camps – just many shades of gray.