“[T]he moment on 10 September 1942 we stepped out of the train in Aalten, I thought: ‘Is the war still going on? Does the persecution of the Jews still exist? Here, everything is so quiet and so different from what we have become used to recently. Here, we may be able to become even more at ease.’ And indeed, we are recovering here.”

These are the words that Jaap Weyel writes on September 22nd, 1942, twelve days after he and his wife arrive at the farm of J.B. Drenthel. This house, in the countryside surrounding the small Dutch town of Aalten, only a few kilometers away from the border to Germany, is where the couple will spend the remainder of the war years until their liberation on March 30th, 1945.1

Fientje Weyel-Aleng and Jaap Weyel (alternate spelling: Weijel), a recently married couple from Amsterdam in their 20s, go into hiding in September 1942, more than two years after the National Socialists invade the Netherlands in May 1940. It is not clear from the diary how they come to this hiding place. From testimony of the farmer’s son, we know that Weyel’s father, a trader in the town of Aalten, asked Drenthel whether he could hide his son and daughter-in-law.2 Hiding on a more or less isolated farm meant that the couple, though for the most part confined to a room, are allowed to “catch some air” outside during dark nights. They chronicle the 933 days they are in hiding, eventually joined by Fientje’s brother Miel, in a diary spanning around 870 pages. The couple keeps their diary together, each writing for a period of two weeks to “prevent that the diary should become monotonous” (from an entry from September 22nd 1942).

Initially expecting to be in hiding only for a very short period of time, hopeful that the war will end soon and they will be free to return home to see their family and friends, Weyel-Aleng’s diary serves as an outlet for their frustrations as well as a recording device for their hopes. Post-war, the couple donate it to the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlog, Holocaust- en Genocidestudies) in Amsterdam, where it has been digitalized and can, since recently, be viewed online.

The diary itself not only allows us insight into the one of many unique hiding experiences of Dutch Jews during World War II, but can also illuminate post-Holocaust usages of wartime documents such as diaries. It also allows us to examine collection practices as well as contemporary digitalization projects of research institutes such as NIOD’s. At the same time, the diary itself is already shaped through documentation practices taking place during and after the war. It is thus also written with a certain public in mind and takes its shape accordingly.

Daily life in hiding

“Today, it has been one year and seven months since we have left Amsterdam; it is beautiful weather today and we… we are going crazy, sick from longing for freedom.” (Fientje Weyel-Aleng, entry from April 10th, 1944.)

The diary itself can be read as a chronicle of the daily lives in hiding of its two writers. It shows how important it was, during life in hiding, to avoid boredom as much as possible and to find a way to pass the days. The couple Weyel-Aleng does its best to stay active, whether through activities such as peeling potatoes, knitting, or physical exercise they carry out in their small space. However, as Jaap Weyel writes, a routine soon establishes itself:

“Really, every day passes as the one before: getting up, washing, getting dressed, cleaning, having breakfast, peeling potatoes or apples, eating, studying, eating, playing card games, waiting until it’s dark, catching some air, eating porridge, sleeping.” (entry from October 4th, 1942).

The reader can also trace the strong emotions present during these years. The two will often recognize how lucky they are to be in hiding and safe from what they fear awaits their friends and family who weren’t as lucky as to find a hiding place. When they complain about their living circumstances and express their wish to go outside and live freely, they quickly feel guilty. They are bothered particularly by their dependence on those hiding them: not only for food, shelter and protection, but also for news from the outside. When the farmer’s family procures a radio, Fientje Weyel-Aleng writes joyfully:

“That would be fantastic! Then we can at least hear the news ourselves and aren’t dependent on others for news.” (entry from December 10th, 1942)

The couple will often express their longing for the war to be over, when they can return to their normal lives and be reunited, they hope, with their families and friends. Still, the fear haunts them that they have become “useless people” to society (entry March 3rd, 1944).

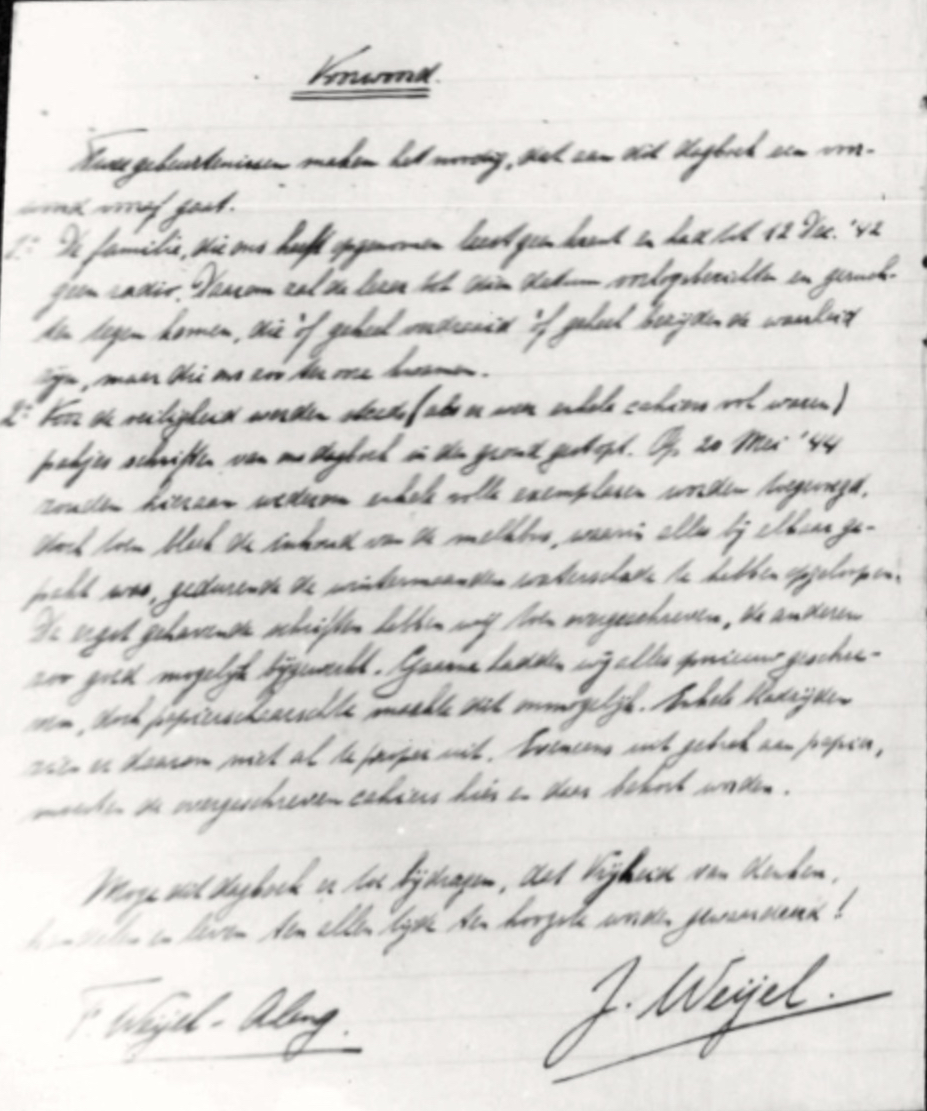

It is difficult to say anything for certain about the intended audience and usage Fientje and Jaap Weyel-Aleng had in mind when they set out to write their diary. The diary includes a foreword and a postscript, in which the diarists thank the family they are in hiding with.

These frames already tell us much about how the authors intended their diaries to be used. By including a basic introduction and conclusion to the diary, giving a background to its content, the Weyel-Alengs intend to make their writing more understandable, showing us they wish it to reach a larger readership.

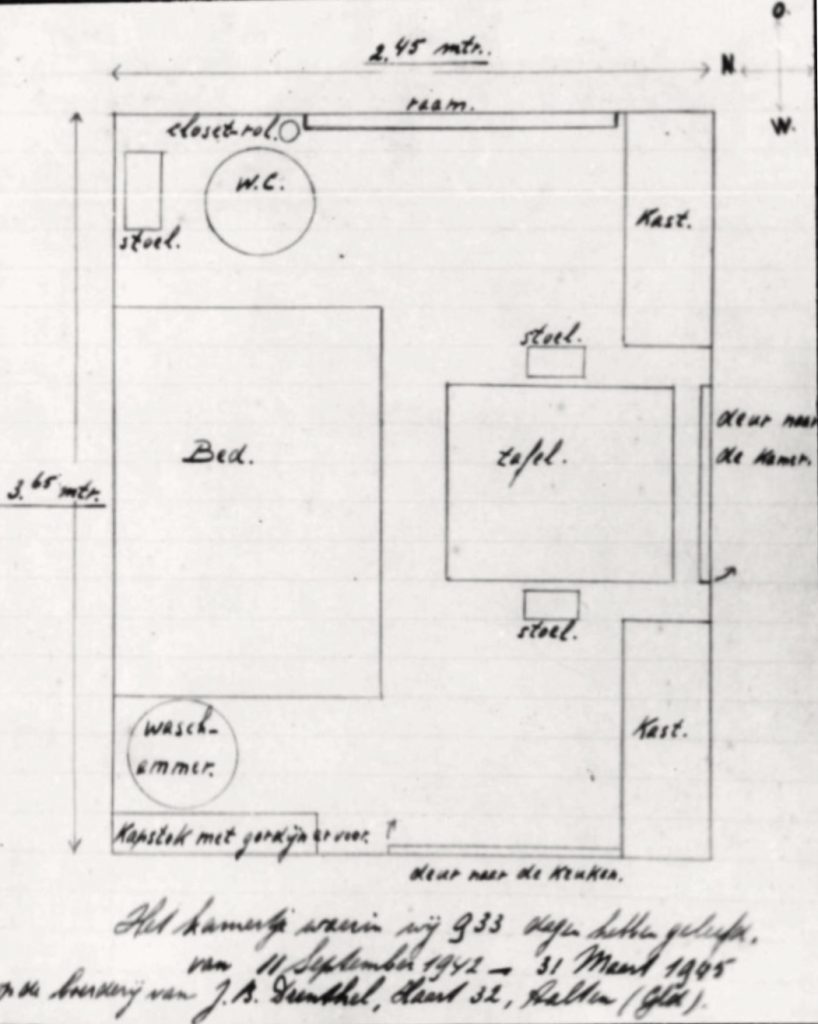

The diary also contains a schematic overview of the room Jaap and Fientje, as well as her brother Miel, hid out in for more than two and a half years.

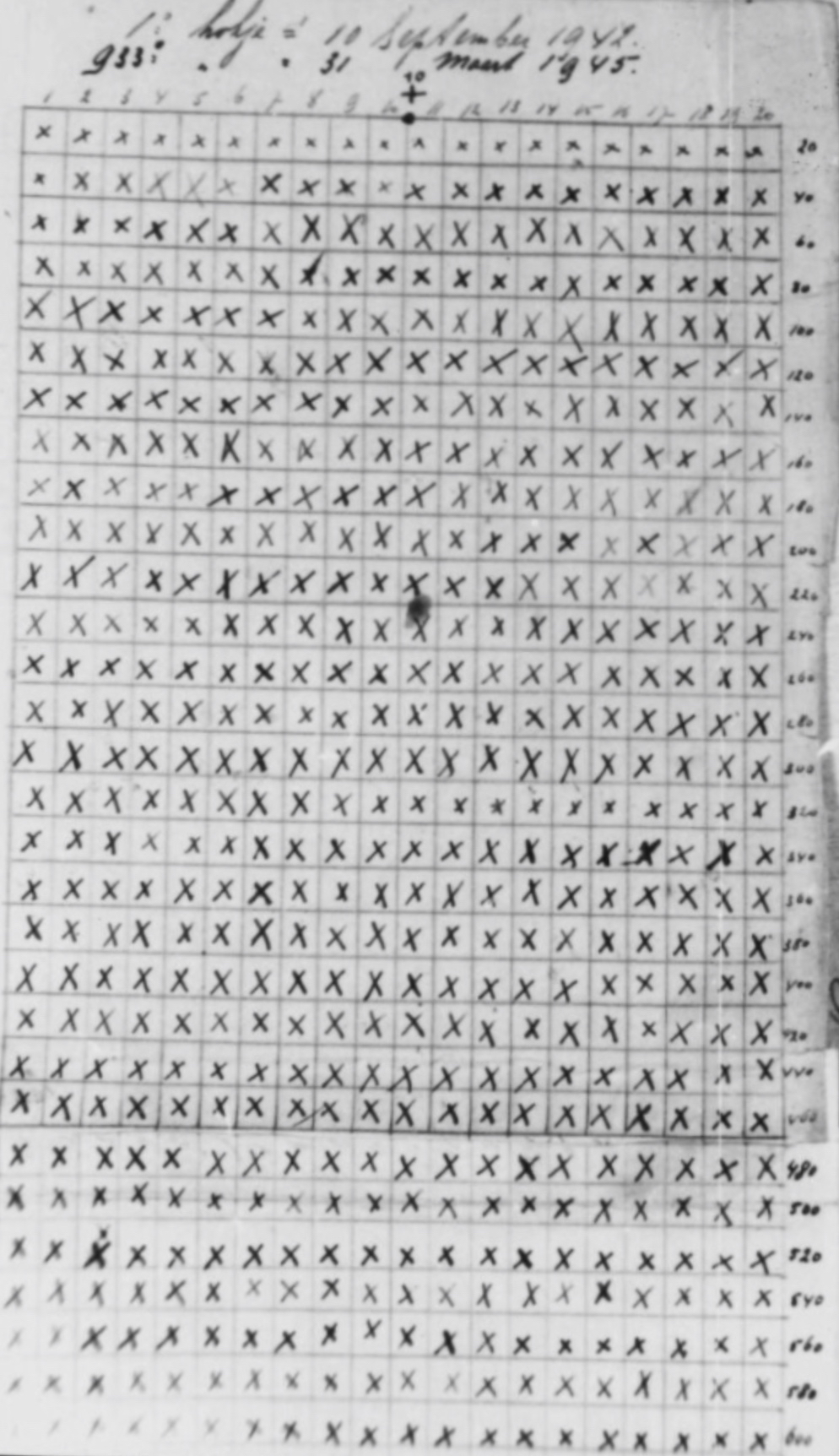

It also includes two sheets on which the two presumably mark the days they spend in hiding.

As previously mentioned, husband and wife alternate writing entries. The reader will notice that their diary entries differ thematically. Fientje tends to express both positive and negative emotions more strongly. Generally, she writes more elaborate and lengthy entries, while Jaap keeps his writing shorter and rarely expresses his worry about the unknown fate of family members. The couple refers and reacts to the other’s entries, meaning that the diary will sometimes take a dialogical form. However, there is hardly a change noticeable in the handwriting, which may lead to the conclusion that the diarists attempted to copy most of their diary legibly and neatly before donating it.

We know that the Weyel-Alengs, at least partially, rewrote their diary. They make this clear in the foreword. Here, they describe that for “safety reasons”, they would bury their full notebooks in an empty milk can. In May 1944, noticing that some of the writings they had so far collected had extensive water damage, they now began to rewrite these parts. Furthermore, they add, “we would have liked to rewrite the entire diary, but this was impossible because of paper scarcity”.

Finding a way into the NIOD’s archival collection

Because of the amount of documents turned in (these included not only diaries, but also memoirs and other reports), the employees at RIOD could make decisions on what to include in their collection. After creating a special section dedicated exclusively to the collection of diaries, the employees began to carry out a selection of donated documents on the basis of quality. Their goal was to curate a collection that would cover as many war experiences as possible, including writings from concentration camps as well as daily life under occupation. Also, because of paper scarcity, the RIOD’s archivists preferred those documents donated to them, rather than having to carry the cost of copying themselves.

Weyel-Aleng’s diary went through this process as well. Attached to the file, as present in NIOD’s archives, is a collection of the correspondence related to the diary. This includes a letter confirming RIOD’s acceptance of the document as well as letters, spaced over the next one and a half years, in which the couple Weyel-Aleng demands the return of their diary, and RIOD, arguing that they face a serious backlog, preventing them from copying and then returning the diary.

Finally, the original diary was returned to its authors after a year and four months. Today, the document is present in NIOD’s archive as printed photographs of handwritten pages. This means that some documents are hardly legible, due to bad quality photographs, which impede the reading process.

Processes of digitalization

Recently, the diary of Jaap and Fientje Weyel-Aleng has been digitalized and is openly accessible through NIOD’s archival interface . Part of Projekt Metarmorfoze, funded by the Dutch government, this partial digitalization of NIOD’s collection is an initiative “to preserve paper heritage”. It is meant not only to heighten visibility and accessibility of documents seen as important to national history, such as the Weyel-Alengs’ diary, but also to guarantee their preservation. Digitalized documents can no longer be accessed in their physical form by researchers or archive guests: access is now exclusively online.

The process of digitalization also illuminates the rights of writers and their work, and the interaction between a public institution and the individuals that donate their possessions to its collections. Jaap Weyel died in 2004, Fientje Weyel-Aleng in 2011. That their diary was digitalized and became accessible online in 2018 shows us that NIOD is in contact with their heirs, who have given their consent that the document be publicly accessible. Following EU copyright law, in the case of lacking consent, there is a 70-yearwaiting period after the author’s death before one can make the document publicly accessible.

We are lucky that this did not happen with the diary of Jaap and Fientje Weyel-Aleng and that it is available digitally to us. It offers insight into what their experience as persecuted Jews during the Holocaust was like: full of daily frustrations and grievances, with instances of hope and excitement as well as fear, sorrow and disappointment, but above all, as relatably human in an unrelatable situation. Most importantly, this diary shows us how important it was, in a situation such as the one that played out on a small farm in the eastern Netherlands, for those who found themselves in a situation almost entirely out of their control, to be able to record and interpret their experiences through their diary.

Thank you to Dr. René Pottkamp, coordinator of archive management and digitalization at NIOD, for taking the time to share his expertise on the process of digitalization. A special thanks also to Sacha van Leeuwen, who allowed me to use her master’s thesis “Selecting the past: the relationship between archives, memory and history investigated through NIOD’s war diary collection (1944 – 2010)” (University Utrecht, 2016) for this article. Thanks also to the staff of the Onderduikmuseum in Aalten, particularly Gerda and Ina Brethouwer, as well as Jan Drenthel, for their help and additional material.

Notes