Officially censored postcards addressed from or to the Terezín (Theresienstadt) Ghetto, are items that are well-represented in the collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague. Correspondence, which was the only option inmates had of communicating with the outside world, was highly controlled and supervised by the SS command. At different times in the ghetto’s history, correspondence was either severely restricted or forbidden by the SS as a form of punishment.

The Terezín Post Office and Transport Department was part of the organisational structure of the “Jewish self-administration” and subordinate to the Department for Internal Administration, which was one of the biggest departments of the ghetto and controlled important areas of everyday life. One of the heads of the Post Office and Transport Department was Philipp Kozower, a former member of the board of the “Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland” and deputy chair of the Jewish Community Berlin.

Ghetto inmates were only allowed to write on official postcards, and at set intervals. Postcards were written to or received from family members and friends, but could also be used as confirmation receipts for packages or permits to send packages. Especially for Jews from Germany and Austria, receiving parcels was very important as they often included food to supplement what they received in the ghetto. Although parcels were more important to the inmates, the number of preserved postcards reveals the scale of the mail system in Terezín. The content of the postcards was strictly regulated and censored. The messages on the postcards had to be written in block letters in German and couldn’t exceed 30 words. Later on, the rule regarding the word limit was abolished.

Some of the inmates tried to contact their relatives through letters and messages that were illegally smuggled from the Terezín Ghetto in order to bypass the strict censors from the “Jewish self-administration” and the SS.

This article includes examples of an officially censored postcard and an illegal letter, revealing the two different faces of the ghetto – the official one, which was supposed to support the illusion of Terezín as a place where the Jews could live peacefully, and the second face – Terezín as a major site of suffering and death for the Jews from the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia and other European countries.

For further information on the Terezín Ghetto visit the Terezín Research Guide.

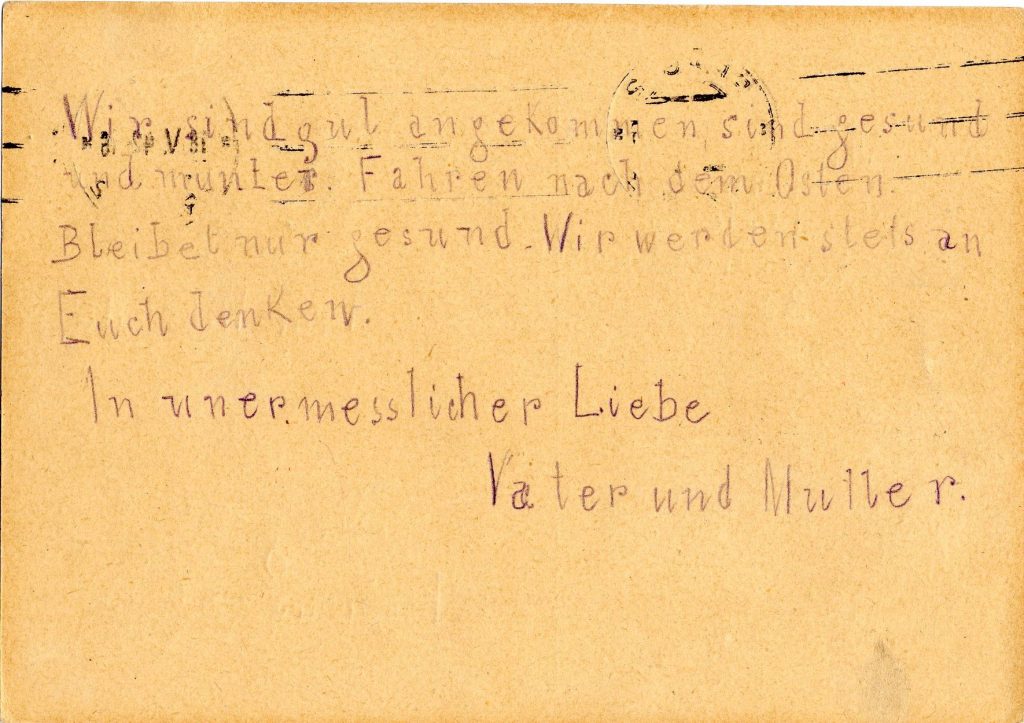

Officially censored postcard from Adéla and Jindřich Kohn

Adéla and Jindřich Kohn were deported to the Terezín Ghetto on May 7th 1942 from Prague. Two days later, they were placed onto the transport to the extermination camps in the Lublin area, where they were murdered at the age of fifty-nine. During their short time in Terezín, they wrote a brief official postcard to their daughter Anna Mikendová, who lived in Prague. Among other things, this postcard shows the inmates’ strategy of condensing information into a very limited amount of words, something they were forced to do.

Translation of the first letter:

We arrived well, we are healthy and vivid. We will go to the East. Just stay healthy. We will always think of you.

With endless love

Father and mother

Censored postcards were usually written in a quite terse style, which can be seen in the text written by Adéla and Jindřich Kohn. It appears that this particular postcard was meant to be a farewell letter to their daughter Anna. Besides the messages relayed in them, the postcards also reveal general information related to the individual Ghetto inmates. Click on the highlighted information on the postcard:

See fullscreen visualisation of the postcard

Mapping the documents was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

Alongside the official and censored postal communication, illegal correspondence occurred throughout the Ghetto existence. Illegal letters were frequently the only way to freely communicate with loved ones outside of Terezín and the only possibility to reveal at least a small fragment of the inmates’ everyday reality and the harsh living conditions in the ghetto. There were various ways to smuggle letters out of Terezín. In the beginning, before the inhabitants of the city were moved out, some inmates succeeded in sending messages with their help. Later on, some correspondence was smuggled out with the help of Czech gendarmes or rail workers. The civilian population as well as the gendarmes often provided these services in exchange for payment. When the smuggling of letters was exposed, severe punishment could be expected. For example, Terezín prisoners were placed onto the next transports to the East, often together with their family members. Some inmates were executed. Despite these threats, the prisoners continued in their illegal efforts to get in touch with their relatives and friends outside the ghetto’s walls.

Rudolf Zenker’s letter addressed to his non-Jewish wife Bohumila is an example of the illegal correspondence from Terezín. Rudolf Zenker was born on September 9th 1886. He had three sisters and three brothers, none of whom survived the war. His sisters and older brother were killed in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Younger brother Emil perished in the Raasiku camp in Estonia. His third brother, Karel, was arrested for illegal activities in 1939 and died two years later in the Buchenwald concentration camp. The lives of the members of the Zenker family reveal how the events of the Holocaust broke up families and their connections with one another, hence the significance of correspondence, especially the illegal kind, in which they could speak freely about their situations.

Before his deportation, Rudolf Zenker lived in Prague together with his non-Jewish wife Bohumila and their adopted daughter Květoslava. As the situation of the Jews in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia deteriorated, pressure on the non-Jewish partners in so-called “mixed marriages” increased as well. Many married couples decided to get a divorce, some of which were real, and others merely formal, which was the case of Bohumila and Rudolf Zenker. We can assume that the purpose of this legal act was to protect the family. Available archival sources don’t reveal any information related to their adopted daughter Květoslava, but it is possible that she would have been considered “mixed race” according to the Nuremberg laws. This might have been one of the reasons why Rudolf and Bohumila decided to divorce. Their correspondence shows that their bond remained strong despite being formally divorced.

Rudolf Zenker was deported to the Terezín ghetto with the H transport, departing from Prague on November 30th 1941. He succeeded in getting in touch with Bohumila and some of his siblings who still hadn’t been deported at the time. In the Archives of the Jewish Museum in Prague, three illegal letters from Rudolf addressed to his “wife” sent from Terezín and one illegal letter from his siblings to the ghetto are preserved.

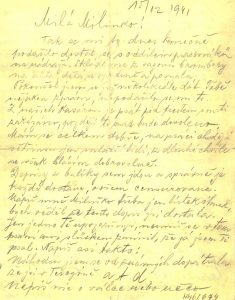

The first letter addressed to his “wife” Bohumila and sent most likely with the help of a rail worker is dated shortly after his arrival in Terezín – December 15th 1941. In it, Rudolf mentions his earlier unsuccessful attempts to send a note to Bohumila. He assures her that he is feeling well and that the camp inmates are permitted to receive parcels, even though some of the content is usually confiscated. Rudolf asks his wife to send some food and begs her not to disclose that he has contacted her. He explains that writing letters in the Ghetto is strictly forbidden and punishable by death. Rudolf gives his “wife” instructions on how to correspond with him across ghetto walls. Several times, Bohumila is sternly warned not to mention the war or the current political situation. He finishes by instructing her to pay 50 crowns to the person who will deliver the letter to her.

Please follow the link for the EHRI collection description:

Translation of the first letter:

15.12.1941

Dear Milinka,

So I finally managed to get to the train station with the workers’ group. We’re unloading potatoes from railway cars and loading them onto cars carefully and slowly. I tried several times to pass on a message to you, but I wasn’t able to. In our barracks, writing is forbidden and punishable by death. Hopefully, they will allow it later. I’m doing fairly well. Mostly young people work, but I volunteer whenever I feel bored.

Letters and packages do get to us and are distributed to the right people, but they are censored. Miluška, write me a note as soon as you can so that I can know that you’ve received this letter. But I must warn you about one thing: you mustn’t mention that I’ve written to you in your letter. Write something like this: My friends told me in passing that you are in Theresienstadt, etc.

Could I ask you please to send me Christmas bread for Christmas? Put it in a

package that weighs about 2-3 kg. Don’t pack cans or other such things into it, they’ll seize those. I still have some bread. We receive 25 dkg per day. It’s not much, but it’s enough for me. Don’t be alarmed by my bad handwriting, I’m writing this inside a freight train. Once more, I must insist: not a single word about my letter.

Miluška, give 50 K (fifty crowns) to the person who will deliver the letter to you. I will find another way to write to you soon.

News about the war reaches us here sometimes.

Give my heartfelt greetings to all of our relatives and friends and for you, a kiss.

Your Rudla

Address: RZ, Sudetenkaserne, no. 55, Theresienstadt, H46/677

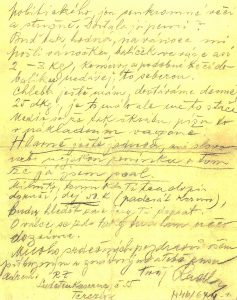

Another two undated illegal letters from Rudolf are preserved in the Archives of the Jewish Museum in Prague. In a short note written on a small piece of paper, Rudolf confirms that he has received a parcel containing bread. He briefly expresses his hope that maybe someday Bohumila could come to the railway station near the ghetto, where Rudolf is working alongside other ghetto prisoners and where they may have a chance to see one another.

Please follow the link for the EHRI collection description:

- Terezín/Theresienstadt (EHRI portal)

Translation of the second letter:

Theresienstadt, Sunday

Dear Miluška,

I am glad that I made it to the train station today with the workers’ group so I can write to you and confirm that I received the bread you sent me yesterday. Thank you from the bottom of my heart, but it wasn’t necessary, I’m fine with the bread I receive. I hope that you’ve already received the letter I sent yesterday. I’m looking forward to the Christmas bread. Don’t send anything else, they’ll only steal it. When it’s nice sometime on Sunday, you’ll come by and see us, right? Greetings to you all, Your Ruda H46/677

The last preserved illegal letter is addressed to Bohumila and Květoslava. Based on its contents, it had to have been written between the second half of December 1941 and January 6th 1942. Among other things Rudolf writes, he asks his “wife” to instruct all of their Jewish friends and relatives who are supposed to be deported to Terezín not to take canned food with them, because all of the cans will be confiscated. He also mentions ghetto rumours that Prague is supposed to be completely free of Jews by the end of February 1942. He again warns Bohumila to reply only in German.

Please follow the link for the EHRI collection description:

- Terezín/Theresienstadt (EHRI portal)

Translation of the third letter:

Dear Miluška and Květuška!

Thank you so much for the Christmas bread and the regular bread. It arrived on time before the holidays, I just wasn’t able to let you know earlier. It’s very dangerous to write here, the punishment for these kinds of offenses is harsh. I heard they won’t be handing out packages until January 6th, so after that please regularly send a two kilo loaf of bread every 14 days, and if possible some pastry. I’m convinced, dear Milunka, that you’ve saved some crackling for me, so please send it. Wrap it tightly in paper without the lard. If you’ve already eaten all of it, so much the better. Tell everyone who is to be transported not to take any cans, not ones with meat, fish, or any other kind. They confiscate them all. Here, anyone who still had any cans left over had to hand them in. Tell them to bring with them instead 50 packages of solid alcohol, a small cooker, and various foodstuffs (barley, rice, and various ingredients to make soup with) because there isn’t much food here. It’s enough for me, but most people are hungry. I think about you every minute. I don’t work and so I’m often bored. How I could be at home shoveling snow, etc. Yesterday, I asked one of the policemen about your visit to Theresienstadt, and he told me that it’s not allowed for anyone to call on us here, so don’t bother coming, it would be in vain. It might be possible later, I’ll let you know. I also hope that they’ll allow us to write someday, but that’s far from certain.

One more thing: Czech letters aren’t delivered to us, only letters in German, so write a couple lines in German. Among other things, mention why you haven’t written. I think they wrote to me from Tábor in Czech and I didn’t receive anything. It would be better if they wouldn’t write, then there would be nothing to fear. Miluška, dont’ shovel the snow by yourself. Get help and pay for it, don’t needlessly overexert yourself.

I still have some crackling and biscuits. I’m saving them and haven’t gone hungry. I even have a piece of Christmas bread left.

Milinka, would you please regularly send me every 14 days starting on January 10th the bread and some pastry, or ¼ kg of salami, but no more than that. The censors steal everything. I’ll let you know in advance if possible.

There is a rumor going around here that Prague should be empty of its Jews by the end of February. I don’t know if there’s any truth to it, but there probably is. Write to Tábor and Budějovice and tell them to prepare themselves and follow my instructions as I have written. The Praguers, too, should get ready. I think it will be peaceful by fall. I so wish we could meet soon.

Greetings and kisses to you both. Ruda

Please say hello to all of our relatives, neighbors, and friends!

If you write, be very careful!!!

I thank Otla for the Christmas bread, it was delicious!

Rudolf Zenker did not remain in the Terezín ghetto much longer. Approximately one and a half months later, he was placed on a transport to Riga that departed on January 9th 1942. With his deportation to the “East,” his correspondence was interrupted and Bohumila never received another word from her husband. She was informed about his death in a letter written to her by Rudolf’s fellow inmate in December 1945.

Literature

ADLER, H. G.: Terezín 1941–1945. Tvář nuceného společenství. Díl II. Sociologie. Brno 2006.

BENEŠ, František – TOŠNEROVÁ, Patricia: Monografie československých a českých známek a poštovní historie. Poště v době nesvobody. 11. díl, svazek II – Pošta v ghettu Terezín. Prague 2004.

BENEŠ, František – TOŠNEROVÁ, Patricia: Pošta v ghettu Terezín. Prague 1996.

LAGUS, Karel – POLÁK, Josef: Město za mřížemi. Praha 2006.

SUŠILOVÁ, Radana – SEDLICKÁ, Magdalena: Ilegální korespondence českých a moravských Židů z koncentračních táborů, in: PÁLKA, Petr (ed.): Židé a Morava XIX., Kroměříž 2013.

Arnoud-Jan Bijsterveld

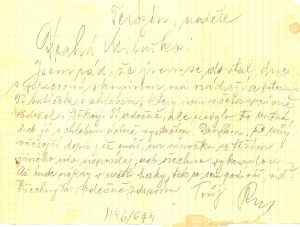

Through her son, I have the contents of letter sent from Theresienstadt by Lore Samson and her father Joseph Samson on April 20, 1945 to her mother and brother in The Netherlands. Their relatives understood they had to take its contents with a grain of salt:

Theresienstadt 20 April ’45

Dearest Mummie and Alfred

How are you doing? If we could just know this. From us you will now get some news at last. Vati and I are doing excellently, really, do believe this literally. Papa looks completely unchanged, as people say who have not seen him in years. He is head in a shoemaker’s workshop and for that reason we are not hungry. Dearest, when you would see me, I am 1.71 m. and weigh 62 kilos. Fine. My red cheeks are still there and often I even put on lipstick! Vati and I really are a handsome couple. Often people call me: Mrs. S., to which our Dad then answers: my daughter! Do not believe that I think the world of myself. I also have a pleasant job. Every day something else, wherever they need us at the moment. We are a bunch of young girls and they call us management! The best Hachsharah job. [other side]

We are also living well. I live with 10 young girls, also in the management in one room bigger that our three together. Lovely. And Vati 2 minutes from there, also nice. Our household is at his place. We eat and cook there. A thousand things I would like to write to you. But what first? I will save it. Hopefully we will be able to tell it orally soon. How is everybody doing? We talk so much about you. I only have a small bad picture of you, Mummie, and of Alfred none. Vati has of you two only bad ones. But this doesn’t matter. Theresienstadt is a little town, 1 square kilometre and we can go walking freely. Nature here is very nice, we sometimes go outside to the farm. We are also going very often to concerts or theatre plays. Also I have been seeing operas here, however not really in costumes. And cooking I also learnt. Well dressed are we also. We have bought things here.

[second leaf]

But to learning one cannot get here. For a while I have been learning [letters in Hebrew] and I already had advanced pretty far, then something interferes and – bang – already one has lost one’s concentration. Mummie, I have to think of your advices so often, and follow them always. When Vati and I deliberate something, we always think what you would have said. We already passed our birthdays. We only cooked a festive meal and we both received nice presents. Also Pesach was good. Vati has offered the Seder. If you want to know more from us, write to the sender of this letter, they are acquaintances of me and the son is a good friend. We would love to get some mail from you. All, all good things and until a soon reunion. A thousand kisses and for all acquaintances many regards from

Your Lore

[other side]

My dear good Mutti [Mother], dear Alfred, from everything Lore wrote to you see that we are healthy and that we are doing fine. Often I say: I wish I only knew that the two of you are doing as well as we, then I would be calmed. You won’t recognize our child anymore, doubtlessly a lady! And she is taking care of me, everyone admires it. We live well, thanks to God, have enough to eat, nothing fails us, only the two of you, but hopefully we will be together again soon. How did things work out for you and what you must have gone through? Until these lines reach you, we certainly have been apart for two years! We wouldn’t have dreamt this. If I only knew where you are and how you are doing and I only hope this letter reaches you soon, so that you know that we are doing fine, believe so, dear Mutti, don’t worry about us! Healthy…. we have, thanks to God, and I am, praise to God, healthy too and able to work and joyful. Bread is baked everywhere and also for us. We are now hoping for a soon and healthy reunion and have yourselves kissed a thousand times. Your Vati [Father]