Introduction

The following document is part of The Wiener Library’s collection entitled ‘Eyewitness reports regarding the November Pogrom’, consisting of 365 eyewitness testimonies collected in the days, weeks, and months following the November Pogrom of 1938, alternatively known as ‘Kristallnacht’ or the ‘Night of Broken Glass’. At the time, Alfred Wiener, the German-Jewish founder of The Wiener Library, operated the Central Jewish Information Office (JCIO) in Amsterdam, which was founded in 1933. Although records about the methodology for gathering this specific set of testimonies don’t exist, Wiener Library staff speculates that they were sourced using the JCIO’s usual modes of data collection: face to face interviews, telephone conversations, letters and written reports, selecting and cropping newspaper articles, and obtaining informal intelligence via conversations and correspondence with other organisations and contacts.

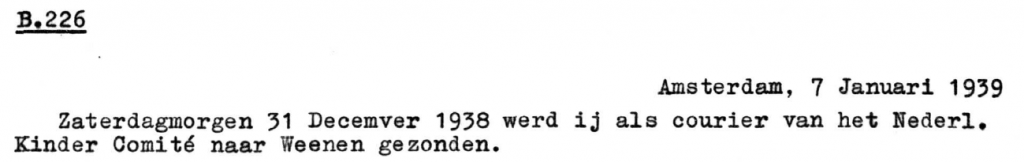

The particular document that will be discussed in this blog, B.226, is an eyewitness report from a courier of the Dutch Kindercomité, predominantly concerning various organisations in Vienna assisting the Kindertransport in December 1938. This account, written on 7 January 1939, stood out from other Dutch-language reports in the Library´s collection due to its unique, critical, and very rich description of several Vienna-based organizations supporting the emigration of Jewish children. Additionally, the report provides a comprehensive picture of the city of Vienna in very turbulent times, right after the November Pogrom in 1938.

Background Information – Vienna 1938

Before 1938, Austria’s capital Vienna was home to approximately 185,000 people who were counted as Jews according to the Nuremberg Laws, making up almost 10% of the city’s population. Vienna had a sizable infrastructure of Jewish organizations, associations, and synagogues, and the well-integrated Jews compromised a substantial percentage of the city’s doctors, lawyers, businessmen, and bankers. All of this changed, however, in March 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed Austria – the so-called ‘Anschluss‘. Once in power, the Nazis quickly applied anti-Jewish legislation, excluding the Jews from Austria’s economic, cultural, and social life. Among other things, Jewish organizations were disbanded, Jewish assets were looted, and the anti-Jewish discrimination increased. Accordingly, Jewish emigration soared and, with the great majority of Jews living in Vienna, the country’s capital became the principal point of emigration from Austria. In spite of the Nazi government’s desire to make Austria ‘Judenfrei’ (lit: ‘free of Jews’), the process of emigration was made very difficult and time-consuming, with Jews, among other things, being forced to stand in long lines and to pay associated fees and migration taxes in order to require the necessary documents.

After the November Pogrom in 1938, which was especially brutal in Vienna, the number of Jews seeking to flee Nazi persecution proliferated. At the same time, the events of ‘Kristallnacht’ raised awareness among the general public and humanitarian aid organizations about the deteriorating situation of European Jews. Accordingly, various humanitarian and private organizations, both Jewish and non-Jewish, used the pre-existing rescue network and started organizing a series of rescue efforts for Jewish children known as the Kindertransport. The first Kindertransport from Berlin departed on 1 December 1938, and the first from Vienna on 10 December. In total, the Kindertransport, which ran until September 1939, saved approximately 10,000 children from the Nazis.

Map Visualisation

Below is a visualisation using a map to show the locations of rescue organisations referenced in the report. Click on a highlighted organisation in the text to see where it was located in 1939.

See fullscreen visualisation of the eyewitness report by a courier of the Dutch ‘Kindercomité’ regarding the situation in Vienna

Mapping the documents was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

Please follow the links for full collection descriptions in the EHRI Portal and Wiener Library Collections Catalogue, as well as the original text and translation of the document:

EHRI collection description:

Wiener Library catalogue description: Eyewitness reports regarding the November Pogrom

Full text and translation can be found on The Wiener Library’s digital resource: Pogrom – November 1938: Testimonies from ‘Kristallnacht’

Cooperation of Rescue Organisations

As mentioned earlier, the eyewitness report discussed in the present blog discusses a variety of interesting topics related to the Holocaust, such as the economic situation of the Viennese Jews and the emigration system in Vienna. The part of the report which appears to be particularly interesting, is the part in which the Kindercomité courier shares his and others’ thoughts on the organization of the Kindertransport. Accordingly, the cooperation between and the selection processes of various rescue organizations assisting the Kindertransport were fairly inequitable and unorganized. As stated by the Head of the Gildemeester-Aktion, for instance, the IKG seemingly preferred Polish and Zionist Jewish children. They gave them preferential treatment by securing a place on the transport for them, while ignoring children from other backgrounds. In a similar manner, as described by the Head of the Society of Friends, the selection processes of the Gildemeester-Aktion were improper, since, among other things, the children of the organization’s staff were selected before others. Altogether, when reading the report, it becomes clear that the various Vienna-based organizations assisting the Kindertransport in the last weekend of December 1938, only regarded themselves, and not the other organizations, as trustworthy. Due to this lack of trust, the organizations limited their cooperation as much as possible and only worked together if needed.

The fact that the Kindertransport from Vienna proved to be so greatly successful, in spite of all of this, leaves one wondering what the experienced rescue organizations could have achieved if they did indeed work together. Could more cooperation between the organizations, have resulted in better insights on the now, often confusing, transports lists for refugees? Could an increase in cooperation have resulted in more equitable selection processes? And, perhaps most importantly, could even more children have been saved?

Interesting Use of Language

Another very interesting aspect of the report written by the courier of the Dutch Kindercomité is the language used in the original report. While the original report was written in Dutch, it was later translated into German for a 2008 publication of the entire collection of (majority German) reports: Novemberpogrom 1938 – Die Augenzeugenberichte der Wiener Library, London. This report, along with the other reports in this collection, were subsequently translated into English by a team of volunteers and edited by Wiener Library Research Fellow, Ruth Levitt, for publication in a 2015 English-language book and companion website entitled Pogrom – November 1938: Testimonies from ‘Kristallnacht’. It is unclear whether the translator based the translation on the original Dutch text, or translated German text.

In January 1939, at the time the original report was written, the so-called ‘Marchant-spelling’ was the official spelling in the Netherlands. The language used in the report, however, is not conform to the guidelines of this spelling. First of all, a great deal of words that are supposed to contain a single vowel, are written with double vowels. For example, ‘Vienna’ is supposed to be written as ‘Wenen’ but is spelled as ‘Weenen’ in the report. Likewise, the Dutch word for ‘only’ is written as ‘eenige’ instead of ‘enige’ Secondly, a number of words are written with ‘sch’ instead of just ‘s’. ‘Oostenrijksche’ (Austrian) and ‘Zweedsche’ (Swedish), for instance, are written in this way instead of ‘Oostenrijkse’ and ‘Zweedse’. Due to the frequency and consistency of the misspellings in the report and the specific time in which the report was written, I believe that the use of language in the report can be understood as intentional, rather than simply the result of inaccurate writing. Accordingly, studying the author’s use of language might give us some insight into the process of creating the eyewitness report, as well as the background of the author.

One possible explanation for the particular usage of language could be that the report wasn’t directly written by the Dutch courier him or herself, but by a non-Dutch, for instance German, staff member at the JCIO. Like all reports in this collection, the author supplied the text by letter, telephone conversation, or other form of communication. The report was then typed by a member of the JCIO staff. The discussed misspellings might have therefore been introduced by the member of staff who typed the report, rather than coming directly from the author’s pen.

Other possible explanations can be found against the backdrop of the great Dutch ‘spelling conflict’ which took place between 1891 and 1940 in the Netherlands. In 1897, an association of Dutch citizens, called the ‘Association for the Simplification of Our Spelling’ (Vereniging tot Vereenvoudiging van onze Spelling) started demanding a simplification of the Dutch language and its spelling. According to the Association, which was led by the linguist Roeland Anthonie Kollewijn, the present spelling – the so-called ‘De Vries and Te Winkel-spelling’ – was too difficult and improbable; thus simplification, whereby unnecessary letters such as ‘sch’ would be deleted, was needed. The demand on the simplification, however, wasn’t received positively by the whole of Dutch society and consequently the great Dutch ‘conflict’ on spelling began. After years of conflict, in 1934, a new simplified spelling, called after the Minister of Education, Arts, and Sciences H.P. Marchant, was partly adopted and implemented; whereas the new spelling became obliged within the educational system, the Dutch government itself still wrote according to the old spelling. Finally, in 1947, the Marchant-spelling was adopted and implemented throughout Dutch society.

Correspondingly, the struggle for and the implementation process of the Marchant-spelling, potentially provides us with explanations for the use of language in the report. First of all, the author could have been of age and more reluctant to adopting a new spelling that was fairly different than what he/she has been using for years. Secondly, the usage of the old spelling could possibly be explained by the author being an opponent of the new, simplified Marchant-spelling. Thirdly, the author could have been living abroad, for instance in Vienna, and therefore was not informed of the (confusing) changes in the Dutch spelling and consequently still wrote according to the old one. On the other hand, the author could have also been a native German speaker, coming from a German-speaking country such as Austria, which preferred a style, like the old spelling, of Dutch closer to German. Lastly, and in my opinion the most likely, the author could have been a government official or someone who worked closely together according to the ‘old’ spelling; the author would write conforming to the De Vries and Te Winkel-spelling when reporting to the government and/or other government officials.

Concerning the proposed questions and explanations in the section above, I would like to emphasize the fact that I only conducted a basic level of research for this blog and, therefore, the blog might be lacking important information. Naturally, in order to answer and find explanations for the previously proposed and akin questions, more research is needed. Nevertheless, I do believe that asking questions and being critical remains important, not only because a more comprehensive historical background of the event is needed, but also because a better understanding of this great rescue mission could potentially provide rescue organizations nowadays with important tools.

As I’m very interested in learning more about the topic and hearing the opinions of others on my thoughts and findings, please feel free to use the comment section below.

Last fall, as part of my studies, I undertook an internship at The Wiener Library in London. After getting to know the Library and its important collection, I worked on various projects, one of them being November Pogrom 1938: Testimonies from ‘Kristallnacht’. While carrying out work on the collection’s Dutch testimonies, I got to know the eyewitness report discussed in the present blog and, needless to say, I became immediately interested. Accordingly, I started researching the information discussed in the report, and, finally, wrote this blog. I enjoyed the process of writing this blog greatly and would like to thank The Wiener Library’s staff for their enormous help. A special thanks to Wolfgang Schellenbacher for his great advice and pictures, and to Jessica Green for her tireless guidance and assistance in editing and formatting this blog and accompanying visualizations.

Bibliography

Bergen, P., “The Gildemeester Organization for Assistance to Emigrants and the Expulsion of Jews from Vienna, 1938-1942” in Terry Gourvish, ed., Business and Politics in Europe, 1900-1970: Essays in Honour of Alice Teichova, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 215-245.

Cohen, D., Zwervend en dolend: de Joodse vluchtelingen in Nederland in den Jaren 1933- 1940: met een inleiding over de jaren 1900-1933, Haarlem, Bohn, 1955.

Dwork, D. and R. J. van Pelt. Flight from the Reich: Refugee Jews, 1933-1946, London, Norton, 2009.

Fast, V.K., Children’s Exodus: A History of the Kindertransport, London, I.B. Tauris, 2011.

MacDonogh, G., 1938: Hitler’s Gamble, London, Constable, 2009.

Michman, J. and B.J. Film (eds.), The encyclopaedia of the righteous among the nations: rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. The Netherlands, (2. Vol), Jerusalem, Yad Vashem, 2004.

Permentier, Ludo, Instituut voor Nederlandse Lexicologie, Nederlandse Taalunie, and Nederlandse Taalunie (eds.), Het Groene Boekje: Woordenlijst Nederlandse Taal, Utrecht, Van Dale Uitgevers, 2015.

Rabinovici, D., Eichmann’s Jews: The Jewish Administration of Holocaust Vienna, 1938-1945, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2011.

Schmitt, H.A., Quakers and Nazis: Inner Light in Outer Darkness, Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 1997.

Wasserstein, B., The Ambiguity of Virtue: Gertrude van Tijn and the Fate of the Dutch Jews, Cambridge, U.S.A, Harvard University Press, 2014.

Wilder-Okladek, F., The return movement of Jews to Austria after the Second World War: with special consideration of the return from Israel, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff, 1969.

Woordenlijst van de Nederlandsche taal, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff, 1954.

![SS-Razzia at the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien, March 1938; Bundesarchiv, Bild 152-64-40 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blog.ehri-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Bundesarchiv_Bild_152-64-40_Wien_SS-Razzia_bei_jüdischer_Gemeinde.jpg)

Judith Haran

What a fascinating discussion! I had no idea about the changeover in spelling. But what I find most comment-worthy is what you pointed out about the relative lack of cooperation among the rescue agencies. In retrospect, knowing what we now know, it seems absurd to think that infighting, resentment, or other such obstacles to cooperation existed — but we know from watching how nonprofits operate in the current day that these irrational factors often get in the way of productive cooperation. (For example, think of the many nonprofits, small and large, that are combatting climate change from various approaches — I don’t see a high level of interoperability/cooperation among these groups.) If only there were some way to give people an “aerial view” of the conflict they are trying to address — a perspective by which they could see exactly how bad things could get in the future, and how trivial or meaningless their inter-agency conflicts truly are. Of course, this would mean coming up for an antidote to human nature, I suppose!!

Micha Knoester

Dear Judith Haran, many thanks for your comment and kind words!

When reading the document for the first time, I was very surprised by the lack of cooperation between the organizations and their reasons for it too. And yes, providing people with such a view could potentially result in resolving conflicts much quicker, but, as pointed out by you as well, the question remains how?

Michaela Raggam-Blesch

Thanks for drawing attention to a subject which has been scarcely noticed! The cooperation and distrust between different aid organizations is worthwhile to observe. In fact, I have have worked on non-Jewish aid organizations in Vienna during the Nazi era in the course of a book (Topographie der Shoah, Jüdische Gedächtnisorte des zerstörten jüdischen Wien, Mandelbaum 2018 / together with Dieter J. Hecht, Eleonore Lappin-Eppel) and an article on this topic should hopefully appear in Yad Vashem Studies some time this year. As to interpreting this document, one needs to be aware that the representative of the Dutch Kindercomité was also confronted with prejudices the different organizations had about each other. In particular, the accusation that Josef Löwenherz, leader of the Jewish community, as a Zionist of Eastern Jewish background would mainly aid children of Zionist or Polish families was a persistent prejudice that lacked historic evidence. Interestingly, in spite of the existing mistrust that this document bears witness to, these non-Jewish organizations also cooperated on various levels, particularly as the persecution of people defined Jewish intensified.

Micha Knoester

Dear Michaela Raggam-Blesch, many thanks for your comments and thoughts! Your work sounds very interesting too, and I will keep an eye out for your article in Yad Vashem Studies. Being aware of the fact that the many existing prejudices between the various organizations could have been unfounded, is indeed of great importance – especially since I did not find any evidence that Löwenherz acted in that way either.

Jorinde

Thank you for this blog. What happened over 75 years ago must never be forgotten!

I have to point out though that there is a simple explanation for the double vowels and the “sch” instead of the letter “s;” that used to be the correct way of spelling Dutch words. Some old letters from my great-grandmother had words spelled like that. I am not sure whether that was still the case during the eye witness report, but the only thing it seems to point to in my opinion is that the person who wrote it was not young and preferred the old spelling.