For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

The development of “witnessing theory”1 and “ego-documents”2 studies in Western academia has stimulated publications3 and online archives4 dedicated to Soviet Jewish life and different types of Jewish identity in post-Soviet countries. In the context of the contemporary relevance of ego-documents studies, I would like to offer my personal experience of studying the Holocaust and Jewish culture in Ukraine. Although each scholarly biography is unique, we can find certain typical strands for the post-Soviet generation of Ukrainian scholars whose “academic youth” came in the 1990s. My personal academic “growing up” in the 2010s coincided with the active development of Jewish and Holocaust studies in Ukrainian academia.

Kharkiv as a multinational city and a centre of Jewish culture in Ukraine

Being born in Kharkiv has very probably influenced my desire to connect my academic career with studies of Holocaust history and World War II in a certain way. Kharkiv was one of the centres of Jewish pre-revolutionary life in the Russian Empire. From 1919 to 1934, Kharkiv served as the capital of Soviet Ukraine, and its socialist history was controversial for several reasons: the Stalinist repressions of the 1930s affected many Kharkiv residents, even famous scientists, intellectuals and poets. On the other hand, before World War II, Kharkiv became the “third city” of the Soviet territory after Moscow and Leningrad in terms of industrial and scientific significance. Many Kharkiv scientists in medicine, engineering, the military arts, and pharmacy were Jewish. Among them, the world-famous nuclear physicists Lev Landau (the Nobel Prize laureate), Anton Valter, Lev Shubnikov, and other reputable scientists worked in Kharkiv research institutes.

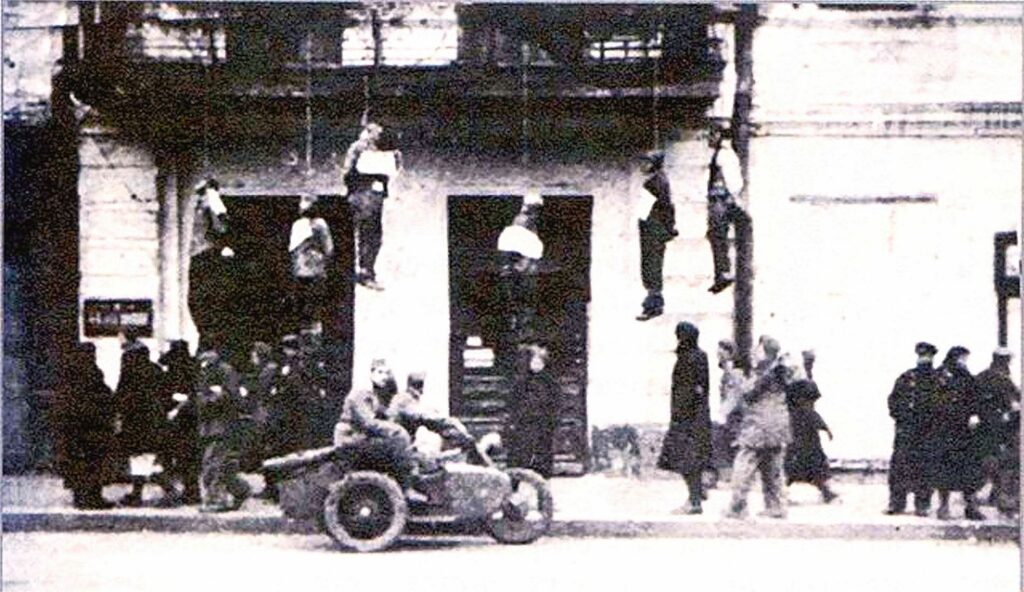

During World War II, Kharkiv struggled with the disastrous Nazi occupation (1941-1943). The Nazis associated the big industrial city of Kharkiv with the technological and academic potential of Soviet Ukraine. During the two years of the occupation, the Nazis widely used a policy of intimidation against Kharkiv locals. In particular, the corpses of executed hostages were hung on the balconies of the central houses of the city. The Kharkiv scientific libraries and physical labs were looted and the socialist monuments were destroyed.5 Every Kharkiv family had relatives who perished during the war, as soldiers or as victims of the Nazi extermination camps or as forced labour in Germany. The population of Kharkiv had decreased by more than a million by the time of the Red Army’s liberation of the city in August 1943. As historian Wendy Lower wrote,6 nearly 4,100,00 Ukrainian citizens died in Ukraine under Nazi rule. Although more than 80 years have passed, some witnesses of those years are still alive, or their children and grandchildren have preserved the memory of the Holocaust and the Nazi occupation within Kharkiv families.

Jewish people constituted up to 19% of the pre-war population of Kharkiv, and Jews composed a significant part of the Kharkiv intelligentsia: scientists, artists, composers, teachers and university professors. During the Nazi occupation, according to various estimates, about 15 thousand Jews were killed by the Nazis in Drobitsky Yar on the outskirts of Kharkiv. This terrible experience was reflected in the shared cultural memory of the war-time generation of the Kharkovites as well as in the attitude of the majority of the inhabitants of Kharkiv to the tragedy of World War II and the Holocaust. Many Kharkiv locals preserved the memories of World War II, the Holocaust and the Nazi occupation as a part of their “family history”.7 That is why the memory of the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust became, in many senses, a kind of “ postmemory” (in Marianne Hirsch’s term8) of the post-war Kharkiv generations, including people of my school age. During the late socialist times, war veterans went to the schools and told the schoolchildren about the everyday experience of the war. Even if some war details were incomprehensible to the children, the schoolchildren could feel the narrators’ emotional state, which impressed them. My grandmother also survived the Nazi occupation in Kharkiv, and, despite the painful memories of the war, she sometimes recalled those years. My scholarly career started at the end of the 1990s. This was a time of significant political and social transformations in post-Soviet society, when Ukrainians chose a new destiny for themselves and were searching for new sources of national and cultural identity. The issues that were absent or prohibited during the Soviet time became more open after Ukrainian independence in 1991. In my circles, many philologists, historians, writers, and journalists became connected to dissident circles of the Soviet times through “tamizdat” and “samizdat” literature. Many people started to attend open lectures and seminars on the Bible, Kabbalah, Jewish history, and Old Testament studies (which were not welcomed in Soviet times).

During my last year of university, I started to learn the Yiddish language and culture in newly launched courses. Yiddish was a spreading language in Kharkiv in the 19th century and even in Soviet times before World War II. Before World War II, several schools and kindergartens in Yiddish existed in Kharkiv, as well as a Hebrew secondary school. Books and newspapers in Yiddish and Hebrew were published in Kharkiv, including the daily Der Shtern (The Star) in 1925–1941 and the journals Di Roite Welt (The Red World) and Sovetishe Literatur. In 1925, the All-Ukrainian Jewish State Theater was opened and performed there until it was moved with the capital to Kyiv in 1934. Additionally, my grandmother had six volumes of works by Sholem Aleichem, which I have also enjoyed reading since childhood.

Despite the high percentage of the Jewish population and the significant impact of Yiddish culture in Ukraine, the Yiddish language was not included in the educational programs of the later Soviet era. I began to study Yiddish in the private courses that emerged in Kharkiv in the post-socialist times, along with a Hebrew language course. While the students on the Hebrew courses had pure pragmatic goals, the teaching of Yiddish had a more cultural character: not only did it involve the study of an almost “lost” language but it was also an introduction to the traditions, cuisine, holidays, music and songs of Eastern European Jews. Short stories by Sholem Aleichem in Yiddish usually served as reading texts in class. The teacher was an associate professor at one of the Kharkiv universities, for whom Yiddish was his family language.

Reflections on the Holocaust in Soviet times

At the same time, the 1990s was the period when the films on the Holocaust, which were semi-banned in Soviet times, were first screened publicly. For example, the prominent film Commissar by Aleksandar Askoldov was shot in 1967 and was banned for twenty years. The premiere was in 1987 made a strong impression on the post-Soviet audience. The traditional point of view was that the tragedy of the Holocaust was not reflected in Soviet public memory. But, in fact, the situation was more complicated. Many Soviet war veterans knew about the genocide of Jews, and the Soviet journalists and cameramen of Jewish origin fixed the tragedy of the Jewish people in the Soviet media of the war time; the famous Soviet writers and poets, such as Illia Ehrenburg, Vassily Grossman, Valentin Kataev, Boris Sluzky, Semen Lipkin, and others wrote about the Nazi genocide of Jews in their works.

The first Soviet literary works devoted to the extermination of the Jews were written in a documentary style and published in the first decade after the end of the war, such as Boris Gorbatov’s story The Unconquered, which was screened in 1945. Evgeni Yevtushenko’s poem Babi Yar became widely known in the Soviet Union and abroad in 1961. At the same time, the Holocaust was not at the centre of attention in Soviet academic history and official commemoration, the Holocaust issue was absent in Soviet school and university teaching. Thus, the Holocaust existed as the Jewish personal, family, and community memory and even artistic memory of the Holocaust (in poetry, films, and literature). On the other hand, it was marginalised in the Soviet public culture.

The significant event that affected the Kharkiv local community was the unveiling of a memorial to the Holocaust in Drobitsky Yar. The tragedy of Babi Yar was widely known among the international academic community, thanks also to the tragic and emotional images in Yevtushenko’s poem, which has been translated into dozens of foreign languages. Unfortunately, the tragedy of Drobitsky Yar in Kharkiv during World War II is still underrepresented in international Holocaust studies, even though this was the place of one of the biggest mass executions of the Jews in Ukraine. Just after the liberation in 1943, the Extraordinary State Commission for the Investigation of the Crimes of the German-Nazi Invaders (created in 1942) and the Jewish Antifascist Committee examined the situation regarding the Nazi crime in Drobitsky Yar. Proof of the massacre came from various Soviet and Nazi sources, interrogations of witnesses, documentary materials and examination by Soviet forensic experts of all the sites of execution and exhumation of the bodies of the Soviet citizens who were shot or burned. Examination of all territories on which bodies of the Soviet people were burnt or buried provides grounds for estimating that the total number of murdered citizens in Kharkiv was about 33,000. Except for Drobitsky Yar, the places of the mass executions in Kharkiv included the site of the mass shooting of children from an orphanage in Sokolniki forest park, the mass graves in Lisopark, the hospital for mentally ill people in Strelechje, the building of the hospital near Sumskaya Street, where wounded Soviet soldiers and officers were burned alive, and many other graves9. Such experience of the war made the memory of the Holocaust and the Nazi occupation the important determining aspect of the cultural memory of Kharkiv locals even many decades after the war.

Over the past three decades, Ukrainian and foreign researchers have done much work to restore the history of the Holocaust in Ukraine. In my opinion, the most comprehensive research focusing primarily on the history of the Holocaust in Kharkiv is the brilliant monograph by historian Anatoly Skorobogatov.10 In his book, Skorobogatov analyses the everyday life of Kharkiv locals during the Nazi occupation, the Holocaust in Yar, the Nazi genocide against the Soviet prisoners of war, the underground resistance fighters, and the Jewish rescuers and post-war memory in Kharkiv. Other informative scientific researches that are more or less related to the history of the Holocaust in Kharkiv, such as the publications by Aleksandr Kruglov,11 the studies by Izhak Arad,12 and a collective monograph by Aleksandr Kruglov, Andrei Umansky, Igor Shchupak13 on the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Ukraine.

The first centres of Holocaust studies in post-Soviet Ukraine

I came to the study of the Holocaust after the defence of my Ph.D. thesis. My main interest was an analysis of how the memory of the Holocaust developed in Soviet and post-Soviet culture. I focused on the fates of the victims of violence and the resistance fighters against the Nazis in images of public memory, literature, cinema and commemoration in the city. Ukrainian scholarly publications in this field were rare in the early 2000s, and the established Ukrainian centres for Holocaust studies started introducing the Ukrainian audience to this area of research through translations of mostly Western authors, as well as the publication of conference proceedings (which were already being held in Ukraine in the early 2000s). Kharkiv was the first city in Ukraine where, in 1996, a city Holocaust Museum was established in the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The founder and director of the Museum for more than twenty five years was Larisa Volovik (1939-2023).14 Volovik was a Ukrainian Jewish community activist, journalist and chief editor of the newspaper “Digest E”, an Honoured Worker of Culture of Ukraine (2004), and a member of the National Committee of Journalists of Ukraine. The museum collection is constantly being updated with materials from personal and family archives, preserving the memory of the crimes against humanity committed during the war.

In 1992, Larisa Volovik initiated the “Righteous Among the Nations” program in Kharhiv. Based on the documents she prepared, approximately 90 residents of Kharkiv were awarded the honorary title of Righteous Among the Nations of Ukraine.15 Volovik also organised screenings of films on the Holocaust and a book exhibition on Jewish culture in the museum. She conducted guided tours of the museum for all types of audiences, and particularly for schoolchildren, students, military personnel, and city guests. For many years, I knew and was friendly with Larisa Volovik. When I worked as a Docentin (2002-2011) and then as a full Professor at the V. Karazin Kharkiv National University (2012-2022), I took my students to the Holocaust Museum in Kharkiv on an excursion, as part of the course “History of 20th-Century Culture”. In 1999, the Tkuma Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies was founded under the leadership of Dr. Igor Shchupak. It evolved into the first national centre for the study of the history of the Holocaust in Ukraine,16 which fruitfully cooperates with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, universities, research, and scientific and educational institutions of Ukraine. It also works with Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Israel, as well as with scientific centres in Canada, France, Israel, Moldova, Germany, Poland, Romania, and the USA. A significant achievement of Tkuma was the creation of the Museum of Jewish Memory and Holocaust in Ukraine in the city of Dnipro in 2012, with a rich exhibition and original objects.

Igor Shchupak, the founder and director of Tkuma, made a major, unprecedented contribution not only to preserving the memory of the Holocaust in Ukraine but also to the institutionalisation of Holocaust studies in the country: as part of school textbooks, scientific publications, conferences, seminars for school teachers, research competitions for schoolchildren and students. Moreover, the Tkuma Institute has translated and published many books on Holocaust history by foreign scholars as well as Ukrainian monographs.17 Dr. Shchupak is the author of over 150 scientific works on the history of the Holocaust, the history of the Jews and the problems of interethnic conflicts in Europe, and an author of history textbooks for secondary schools that are recommended by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine.18 Dr. Shchupak frequently organised educational seminars for Ukrainian historians, journalists, and teachers at Yad Vashem in Israel and the International Research Center “Yahad-In Unum” in Paris. Since 2007, I regularly presented at conferences devoted to Holocaust studies held at the Tkuma Institute. Since 2011, I have also recommended that my students and postgraduates participate in the conferences on Holocaust studies organised by Tkuma.

In 2002, the Ukrainian Centre for Holocaust Studies was founded in Kyiv, 19 under the direction of Anatoly Podolsky, who defended the first doctoral dissertation in Ukraine on the history of the Holocaust.20 The main topics of scholarly research at the Centre are the regional features of the Holocaust in Ukraine, reflections on Holocaust in media, problems of anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial, and comparative studies of the Holocaust and other genocides. The Centre holds conferences, seminars and summer schools for Ukrainian teachers and students. Since 2005, the Centre has published the scientific journal Holocaust and Modernity: Studies in Ukraine and the World and the information and educational bulletin Lessons of the Holocaust. As part of its scientific and educational programme, the Centre translates and publishes books on the history of the Holocaust and genocides.21

Since the mid-2000s, there has been a network of Holocaust researchers in Ukraine, with Semion Orlyansky (1928-2013) of Zaporizhzhia making a significant contribution to the development of Holocaust studies.22 For over fifteen years, he regularly organised a conference over two to three days on Jewish and Holocaust studies in collaboration with the Zaporizhzhia University. It was the first annual conference on Holocaust studies in Ukraine and it was particularly prestigious and of great interest as it was attended by many scholars of Holocaust and Jewish studies as well as poets, writers, social activists, and journalists. At this conference, graduate students had the opportunity to present their first research on Jewish topics. The most interesting presentations of this conference were published.23 Orlyansky himself studied different problems of the Holocaust in Ukraine, Jewish history and memory of the Holocaust.24 After Orlyansky’s passing, Igor Shchupak continued to organise the conference on Holocaust and Jewish studies for Ukrainian scholars, where I took part many times. It was a significant contribution to the development of Holocaust studies in Ukraine.

My contribution to Jewish, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

I started my research in the field by familiarising myself with foreign historiography and methodology of the Holocaust. I was awarded several fellowships at international centres and Western universities that impacted on my scholarly approach. In particular, during my fellowship at the Kennan Institute in 2001, I had the opportunity to visit the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC and to study the scale of the Holocaust and the specifics of the Holocaust in different regions of Europe, as well as the social and national composition of the victims of the Nazis in addition to Jews (Soviet prisoners of war, Roma, homosexuals, disabled people, representatives of the East Slavic race, communists and members of the anti-Nazi resistance, black people, and others). I have published the materials and ideas collected during the fellowship in several papers.25

One of my most inspiring experiences was the three-month fellowship at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam, working with historian Karel Berkhoff. As part of this fellowship, I took an intensive German course, which enabled me to work with German sources, and participated in weekly seminars for postdoctoral scholars organised by Karel Berkhoff. I also visited museums connected with Holocaust history, particularly the Anne Frank Museum and the Dutch Resistance Museum in Amsterdam. After this fellowship, I published several papers, in particular on Jewish themes in Sergei Eisenstein’s films26 and on philosophy after Auschwitz.27

The fellowship at the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich in 2016 significantly impacted my studies, thanks to the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) fellowship programme. I was given the opportunity to work with German, Czech, Polish, Ukrainian, Russian and English-language sources and testimonies of the former victims of the Nazi concentration camps, Jewish ghettos, and camps for the prisoners of war. As a result of this fellowship, I published several papers on the cultural and religious understanding of the Holocaust.28 In addition, of great importance for me in gaining new knowledge and introducing new directions of research into the history of the Holocaust and its memory in Ukrainian education were fellowships at Yad Vashem as well as international conferences, which provided the opportunity to hear presentations by colleagues from different countries.

Seldom-studied materials

In 2010, I defended my second doctorate for the Habilitation in the philosophy of the Other and racial, gender and national Otherness in culture. The problem of Jewish Otherness, the status of Jewish emigrants and victims after the Holocaust and in the second half of the 20th century, was one of the aspects of my dissertation and of my ensuing monograph, The Face of the Other: Images of the Others in Cultural Anthropology.29 This monograph and several subsequent chapters in collective monographs were published in Germany and the Czech Republic where I focused on constructing the Soviet and American post-war memories in the context of the Cold War ideologies30 and on the contribution of scientists in the anti-Nazi resistance.31

As part of my most recent focus on the participation of scientists in the anti-Nazi resistance, I have started to study the early Soviet sources on the history of the Nazi occupation, which were published in a small quantity and are now a bibliographical rarity now. In particular, the witness material of Soviet medics regarding their activity during the war and the Nazi occupation in Kharkiv, through memoirs devoted to the doctor Aleksandr Meshchaninov (1869-1969).32 Meshchaninov was a surgeon and directorof a civilian hospital during the Nazi occupation in Kharkiv, who secretly provided medical treatment to Kharkiv Jews and wounded Soviet prisoners of war despite the personal risk to his life and the lives of his family and the hospital staff. Meshchaninov provided not only the required medical treatment but also had false passports made for these people and helped them to escape from captivity and thus to survive. The memorial bust to Aleksandr Meshchaninov was unveiled in 2006.

Another critical but understudied source on the Nazi occupation and the Holocaust in Ukraine is the book by Albert Tsessarsky, Notes of a Partisan Doctor,33 based on his military diary, published in 1956. Albert Tsessarsky was a Soviet Jew and a chief doctor in a Soviet partisan unit in the Western Ukraine during World War II and the Soviet struggle against Nazi Germany. His book was not a subject for analysis in Soviet times. Nonetheless, it stimulated my research interest, so I analysed Tsessarsky’s book at several levels: as a testimony of the Holocaust and as the medical and fighting experience of a Soviet Jewish doctor.34

Holocaust Memory: Drobitsky Yar

Also I have investigated development of memory of the Holocaust during Soviet and post-Soviet times.35 The traditional point of view is that the Holocaust was not reflected in Soviet public memory. But, in fact, the situation was more complex, and contemporary scholars wrote about the “memorial activism” of Holocaust survivors who took the initiative for the installation of the first memorial signs on the sites of the murders of Jews in the Soviet territories. In Kharkiv, the first commemorative sign to the Jewish victims of Drobitsky Yar was a small obelisk with the inscription “To the victims of fascist terror”, which was erected by the architect Aleksandr Kagan in 1955. This obelisk was officially established after Kagan’s numerous appeals to the state authorities for the state’s permission to erect it. However, the official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Nazis was built in Kharkiv only after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In 1988, Yevgeny Lysenko and Viktor Boiko founded the Drobitsky Yar Program at the Kharkiv branch of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.36 They collected letters from relatives of the victims and created a Holocaust card index of the Victims of the Holocaust. On May 9, 1989, a big rally took place at the site of the tragedy, where a decision was made to form the Drobitsky Yar Organizing Committee and create a Monument in memory of the Jewish victims of the Nazis. The rally was attended by the city authorities and the famous Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, who at that time was a People’s Deputy of the Soviet Union for Kharkiv.37 In 1991, the first president of independent Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk, apologised to the Jewish people for the participation of some Ukrainians in the Holocaust. In 1991, the organising committee made a decision “on perpetuating the memory of the victims of fascism buried in Drobitsky Yar” and announced an open competition for a memorial complex. The winners were the co-designers Alexandr Leibfreid and Viktor Savenkov Aleksandr Tkach. A large Memorial Menorah was erected in Drobitsky Yar in 2002. On the front of the Menorah is inscribed: “In Drobitsky Yar from December 1941 to January 1942, the Nazis killed more than 16 thousand prisoners from the Kharkiv Jewish ghetto – the elderly, women and children – just because they were Jews.”

In 2005, on the eve of the anniversary of Kharkiv’s liberation from the Nazis, the Hall of Names was opened, where the names of the dead Jews were placed on the walls. Among the 16,000 dead, the names of 4,000 killed were investigated. Along with Jewish people, Soviet prisoners of war and mentally ill people were also shot in Drobitsky Yar. In total, according to the State Archives of the Kharkiv Region, about 16-20 thousand people were shot in Drobitsky Yar. It is important to note that both the Chief Rabbi of Kharkiv and the Kharkiv Orthodox priest consecrated the construction of the Drobitsky Yar Memorial in 1994, in this way emphasising that both the Jewish and non-Jewish communities of Kharkiv recognised the Holocaust as a great tragedy. Thus, the establishment of a memorial in Drobitsky Yar was a commemorative expression on the part of Kharkiv’s official, national, regional, Jewish and Christian communities.

(Source: author)

(Source: Wikimedia)

To summarise, the strand of memory does not stop at the memorial place devoted to Drobitsky Yar. Since the mid-2000s, the issue of the Holocaust as a national tragedy of the European Jews has been slowly introduced into the public culture and teaching in Ukraine. Many Kharkiv schools and universities have introduced courses on the Holocaust and genocide history in their curriculum. In particular, during my lectures on the history of the 20th century, I organise visits for my students to the Kharkiv Holocaust Museum and the Drobitsky Yar memorial as a place of Holocaust tragedy. I also give a lecture on the Holocaust and anti-Nazi resistance and on the memory of the Holocaust in contemporary culture. Some of my students have expressed a desire to further their studies and have prepared papers on the topics of “Holocaust Memory in Art”, “Rescuers of Jews in Kharkiv”, “Images of the Holocaust in Cinema (of different countries)”, and more.

It should be noted that significant changes have taken place in contemporary Ukraine compared to the Soviet period: the tragedy of the Holocaust has become a part of the national public memory in Ukraine, and commemorations for mourning the victims of the Holocaust take place at the state level. The topic of the Holocaust has been incorporated into many school textbooks. School teachers can participate in the seminars and summer schools on the memory of the Holocaust, which are organised by both the Israeli Yad Vashem Center and Ukrainian public educational organisations, such as the Tkuma Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies under the direction of Igor Shchupak, the Ukrainian Center for the Study of the History of the Holocaust in Kyiv under the direction of Anatoly Podolsky, as well as regional community centres in Kharkiv (Beit Dan), Chernihiv, Lviv, the Holocaust Museum in Odesa under the direction of Pavlo Kozlenko, and elsewhere. Holocaust studies are developing in state universities, such as V. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Zaporizhzhya State University, and Odesa State University. Of course, in many respects, this is happening due to the personal initiative of the most active professors. However, if in the 1990s Holocaust studies in Ukraine were represented mainly by translated foreign academic works, now, after a quarter of a century, a generation of independent researchers has developed in Ukraine who dedicate their papers and monographs to the acute topics of the Nazi occupation, the Holocaust in Ukraine, and post-Holocaust memory.

It can thus be said that the Ukrainian academic community and society as a whole have made a big step towards accepting and studying the memory of the Holocaust. The most indicative example of this is the fact that it continues even during the current Russian-Ukrainian war. Despite the constant shelling, problems with electricity and the internet, the staff of the Ukrainian Holocaust study centres in Dnipro, Kyiv, and Odesa continue to carry out their educational tasks in Ukraine heroically, prepare textbooks for schoolchildren, hold seminars and conferences for teachers, and organise memorial events dedicated to important dates in history.

- Wieviorka, Annette, The Era of the Witness (Translated by Jared Stark). Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2006; Hellbeck, Jochen Revolution on My Mind: Writing a Diary under Stalin, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006. ↩

- Fitzpatrick Sheila and Slezkine Yuri, In the Shadow of Revolution: Life Stories of Russian Women from 1917 to the Second World War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000; Fulbrook Mary and Rublack Ulinka, “In Relation: The ‘Social Self’ and Ego-Documents”, in German History, Vol. 28, no. 3, 2010, 263–272; de Jong, Steffi, The Witness as Object. Video Testimony in Memorial Museums. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2018; Haim Sperber, “The Usage of Ego-documents in Jewish Historical research”, in Jewish Culture and History, Vol. 24, no. 2, 2003, 123–127; Sepp, Arvi, and Augustyns, Annelies, “Jewish ego-documents in Holocaust studies: the use of the diary as a genre and a source” in Jewish Culture and History, Vol. 24, no. 2, 2003, 232–250. ↩

- Altshuler Mordehai, Religion and Jewish identity in the Soviet Union, 1941-1964 (Translated from Hebrew by Sternberg Waltham). Massachusets: Brandeis University Press, 2012; Kliueva Vera, “‘Of course, I’m a Jew, but I’m a Soviet Jew’: Multiple Identities in the Memoirs”, in Quaestio Rossica,Vol. 9, no. 4, 2021, 1187–1204. ↩

- For example: Digital Archive of Soviet Jewish ego-documents: Zemelah.online; https://www.blavatnikarchive.org/collection/veteran-testimonies (collection of 1,200 video interviews with Jewish men and women who fought in the Soviet armed forces and partisan detachments during World War II). ↩

- Скоробогатов Олександр, Харків у часи німецької окупації (1941-1943). Харків: Прапор, 2006, 66. ↩

- Lower Wendy, Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine. University of North California Press Chapel Hill and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2005, 2. ↩

- The personal stories and documents of Kharkiv locals during the Nazi occupation and Holocaust can be found in the Kharkiv Holocaust Museum, opened in 1996 by founder and director Larisa Volovik (http://holocaustmuseum.kharkov.ua/index.php/smi-o-nas-pishut) and in the Kharkiv Historical Museum, named after N. Sumzov (https://museum.kh.ua/eng.html). ↩

- Hirsch Marianne, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012. ↩

- Ляховицкий Юрий, Попранная мезуза. Книга Дробицкого Яра: Свидетельства, факты, документы. Харьков, 1991; Скажи, Дробицкий Яр…: Очерки. Воспоминания. Документы. Стихи, Edited by В. Лебедева, П. Сокольский. Харьков: Прапор, 1991; Круглов Александр, Хроника Холокоста в Украине. Днепропетровск: Ткума; Запорожье: Премьер, 2004; Скоробогатов Анатолий, Харків у часи німецької окупації (1941-1943). Харків: Прапор, 2006; Sukovata Viktoria, “The Holocaust in South-Eastern Europe: The Case of the Ukrainian Kharkiv Region”, in Holocaust: Studies and Cercetari. Bucharest: Elie Wiesel National Institute for Studying the Holocaust in Romania, 2015. vol. 7, Issue 1, 137-156. ↩

- Скоробогатов Анатолий, Харків у часи німецької окупації (1941-1943). Харків: Прапор, 2006. ↩

- Круглов Александр, Истребление еврейского населения на Левобережной Украине (зона военной администрации) в 1941–1942 гг. In: Катастрофа і опір українського єврейства (1941–1944 рр.): Нариси з історії Голокосту і Опору в Україні / Ред. та упоряд. С. Я. Єлісаветський. К., 1999. С. 172–201; Круглов Александр, Хроника Холокоста в Украине. Днепропетровск: Центр «Ткума»; Запорожье: Премьер, 2004. ↩

- Aрад Ицхак, Катастрофа евреев на оккупированных территориях Советского Союза (1941–1945). Перевод с англ. Днепропетровск: Центр «Ткума»; ЧП «Лира ЛТД»; М.: Центр «Холокост», 2007 (Arad Y. History of the Holocaust. Soviet Union and Annexed territories in 2 volumes. Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2004). ↩

- Круглов Александр, Уманский Андрей, Щупак Игорь, Холокост в Украине: немецкая военная зона, румынская военная зона, дистрикт «Галичина», Закарпатье: монография. Днипро: Украинский институт изучения Холокоста «Ткума», 2017. ↩

- Бойченко Наталья, Померла харків’янка, яка присвятила життя вшануванню та збереженню пам’яті загиблих in https://gx.net.ua/obshhestvo/region/pomerla-harkivyanka-yaka-prisvyatila-zhittya-vshanuvannyu-ta-zberezhennyu-pamyati-zagiblih-foto.html (Accessed: 23. 10. 2024). ↩

- “Основатель Харьковского музея Холокоста Лариса Воловик награждена за сохранение наследия“ in Евреи Евразии: http://jewseurasia.org/page6/news69546.html (Accessed 23. 10. 2024) ↩

- Український Інститут Вивчення Голокосту „Ткума“: https://tkuma.dp.ua/ru/pro-nas. ↩

- For example: Еврейское сопротивление в Украине в период Холокоста: Сборник научных статей / Под ред. Михаила Тяглого. Днепропетровск: Центр «Ткума», 2004; Михман Дан, Историография Катастрофы. Еврейский взгляд: концептуализация, терминология, подходы и фундаментальные вопросы. Translated from English. Вып.1. Днепропетровск: Ткума, 2005; Воспоминания „детей войны“ о войне и Холокосте, ed. by Лариса Пелюх, Днепропетровск: Ткума, 2016; Давлетов Александр, Подготовка “поколения волков”: выучка будущих исполнителей Холокоста (Очерки молодежной политики НСДАП в 1922-1939 гг.) Днепропетровск: Ткума, 2017; Холокост: художественные измерения украинской прозы ed. by І. Павленко, Днепропетровск: Ткума, 2019, and others. ↩

- For example: Щупак Игорь, “Феномен спасителей евреев в современной украинской политике памяти и сфере образования“ in Ежегодник 5781, Институт Евро-Азиатских Еврейских Исследований: https://institute.eajc.org/ ; Щупак Ігор, Голокост в Україні. Випуск № 2.: Мультимедійний посібник. Дніпропетровськ: Ткума, 2009; Щупак Ігорь, Евреи в Украине: Вопросы истории и религии с древнейших времен до Холокоста: учебное пособие для учащихся старших классов среднеобщеобразоват. учеб. Заведений. Днепропетровск: Украинский институт изучения Холокоста. «Ткума», 2015, etc. ↩

- Український Центр Вивчення Історії Голокосту: https://holocaust.kyiv.ua/. ↩

- Подольский Анатолий. Нацистский геноцид евреев Украины (1941-1944) : автореферат дис. кандидата исторических наук : 07.00.09. Киев, 1996. ↩

- Лауер Венді. Фурії Гітлера. Німецькі жінки у нацистських полях смерті, пер. з англійської В. Іваненко. Київ : Укр. центр вивч. історії Голокосту, 2020; Кувалек Роберт, Табір смерті у Белжеці, Пер. з польської О. Колесник. Київ: Український центр вивчення історії Голокосту, 2018; Переслідування та вбивства ромів на теренах України у часи Другої світової війни: Збірник документів, матеріалів та спогадів, Авт.-упор. Михайло Тяглий. Київ: Український центр вивчення історії Голокосту, 2013; Злочини тоталітарних режимів в Україні. Київ: НІОД; Український центр вивчення історії Голокосту, 2012, etc. ↩

- Щупак Игорь, “Семён Федотович Орлянский: учёный и организатор науки“ in Запорожские еврейские чтения. Днепропетровск: Институт «Ткума», 2013, 4-20. ↩

- For example: Суковатая Виктория, “Еврейская идентичность и исследования иудаики в западных университетах” in 11-ые Запорожские еврейские чтения, Запорожье: Запорожский национальный университет, 2007, 341-347. ↩

- Орлянский Семен, Орлянский Семён, История евреев Запорожья. Книга 1 : 1780 – февраль 1917 г., Харьков-Запорожье: Еврейский мир, 1997; etc. ↩

- Суковатая Виктория, “Гендерные и сексуальные политики в дискурсе послевоенной антропологии” in Философские науки, 2006, № 5, С. 54-74; Суковатая Виктория, “Образ еврея как национально-гендерного Другого в русских общественных дискуссиях конца Х1Х века” in Евреи и славяне. Киев-Иерусалим, 2008. Том 19, 266 -287. ↩

- Суковатая Виктория, “Другой” Эйзенштейн: “Основатель большевистского кино”, или “Еврей из Риги”? in Евреи в меняющемся мире. Рига: Центр иудаики Латвийского университета, 2009. С. 240-247. ↩

- Суковатая Виктория, „Философия после Освенцима“: рефлексии военного насилия в западном и постсоветском сознании“ in Социология: теория, методы, маркетинг. 2010. № 2. С.112-132. ↩

- Суковатая Виктория, „Еврейская тема“ в творчестве Ж.-П.Сартра“ in Запорожские еврейские чтения. Днепропетровск: Ткума, 2012. С. 213-224; Sukovataya V. “Perception of the Holocaust as a Source of ‘the Other’ Philosophy in the Second Half of the 20th Century” in: Holocaust Studies: A Ukrainian Focus. Dnipro: Tkuma, 2019. p. 132-143; Суковатая Виктория, “Память о Холокосте и ее философское осмысление в западноевропейском и советском обществах” in Евреи Европы и Ближнего Востока: наследие и его ретрансляция. Петербургский институт иудаики, 2017. Вып. 12. С. 219-225. ↩

- Суковатая Виктория, Лицо Другого: телесные образы Другого в культурной антропологии. Харьков: ХНУ, 2009. ↩

- Sukovata Viktoriya,“The Holocaust Response in American and Soviet Cultures as a Reflection of the Different War Experiences and the Cold War Politics.” In: Hans Krabbendam/Derek Rubin (eds.), American Responses to the Holocaust. Translatlantic Perspectives, Frankfurt a. M.: Peter Lang Verlag 2017, pp.131–150. ↩

- Sukovata Viktoriya, “Scientists-Emigres in the Anti-Nazi Resistance. Fate and Fame”, in Michal Šimůnek (ed.), Science, Occupation, War: 1939–1945. Prague: Czech Academy of Sciences 2021, 437-459. ↩

- Лесовой В., Перцева Ж. “Харьковские медики в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг” in: Вустами спогадів і пам´яті. Вища медична школа Харківщини в роки Другої світової війни : мемуари та публіцистика, Харків. : ХНМУ, 2015, 118-132. ↩

- Цессарский Альберт, Записки партизанского врача. Москва: Советский писатель, 1956. ↩

- Суковатая Виктория, “Рецепции войны и Холокоста в советской послевоенной литературе: документальная повесть А. Цессарского «Записки партизанского врача»” in Проблемы истории Холокоста: украинское измерение. Днепр: Ткума, 2018. Вып. 10, 94-126. ↩

- Суковатая Виктория, “The Holocaust in South-Eastern Europe: The Case of the Ukrainian Kharkiv Region.” In: Holocaust Studies, Vol. 7 (2015), № 1, pp. 137–156. ↩

- Карпюк Геннадий, “Трагедия, о которой кое-кто не очень хотел знать” in Зеркало недели, 22.12.2006: https://zn.ua/SOCIUM/tragediya,_o_kotoroy_koe-kto_ne_ochen_hotel_znat.html. ↩

- Заир-Бек Якуб, Вассерман Михаил, “ Земля дышала, земля стонала…Дробицкий Яр. К 80-летию трагедии в Харькове“ in ИСРАГЕО Журнал географического общества Израиля, 28.10.2021: https://www.isrageo.com/2021/10/28/drobi430/. ↩