The annual Workshop on the History and Memory of National Socialist Camps and Killing Sites, previously known as the Workshop zur Geschichte und Gedächtnisgeschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, has been convened since 1994. Originating in Germany, the workshop has progressively expanded both its geographic and thematic reach in recent years. This international gathering, led by emerging scholars and practitioners, offers a collaborative and interdisciplinary platform for the study of Nazi camps and killing sites. Key topics include persecution, forced labor, mass murder, and the Holocaust, along with their representation and commemoration across diverse historical contexts. Designed for scholars and practitioners who do not yet have a PhD, the workshop aims to foster a collective and supportive environment for the exchange of ideas, methodologies, and research findings, drawing on a wide array of sources. As the workshop’s emphasis on sources aligns with the EHRI Document Blog, the 26th Workshop team and EHRI are joining forces for the first time to publish a special issue showcasing papers presented at the last workshop held in Łódź in September 2023, focusing on the themes of “Bodies and Borders.” In addition to this special issue, a conference volume featuring a selection of chapter-length papers from the 26th Workshop will be published in the series of workshop proceedings with Metropol Verlag, Berlin.

Bodies and Borders

The 26th Workshop focused on the analytical categories “Bodies and Borders” to critically assess spaces of Nazi ghettoization, concentration, and killing sites. These themes can be understood in physical form as well as in abstract terms. The spatial boundaries of concentration camps and killing centers were clearly demarcated whereas other sites of murder and mass violence were often more open and accessible geographical spaces. Bodies were at the heart of these places: the physical bodies of victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. With these themes in mind, the papers transgressed established frontiers between disciplines and were organized into four distinct panels: Sealing, Crossing, Transcending Borders; Materialities of Bodies; Negotiating Bodies: Friendship, Sexual Violence, and Social Dynamics in the Holocaust; and Proximities to Violence. The below contributions are derived from individual presentations which represent the scope of the workshop’s interwoven themes of “Bodies and Borders.” (For the full conference report, see: Hannah Sprute and Aliena Stürzer, “Conference Report: Bodies and Borders. 26th Workshop on the History and Memory of National Socialist Camps and Killing Sites,” H-Soz-Kult, 4 December 2023, http://www.hsozkult.de/conferencereport/id/fdkn-140279)

This article analyses the auditory experiences of the Warsaw Ghetto inhabitants to understand what they reveal about life within the ghetto. Grounded in a vast array of personal testimonies, this research provides a more nuanced understanding of the ghetto auditory daily realities. The focus on the Warsaw Ghetto presents an opportunity to examine how its inhabitants navigated and made sense of their auditory world under extreme circumstances, offering insights into the intricate interplay between sound, silence, and survival.

This approach allows a multifaceted exploration of the ghetto’s soundscape, from the omnipresent noise of overcrowded streets and the melodies of hope and despair performed by musicians to the oppressive silences that marked the end of this period of Shoah. Through these lenses, the article explores how sound served as a medium of resistance, a marker of community, and a harbinger of doom, thereby enriching our understanding of the ghetto inhabitants’ embodied experience. It invites the reader to consider the profound ways in which sound can shape our perception of space, identity, and community, especially in contexts of violence and persecution.

This approach contributes to the field of Holocaust Studies and sheds light on the sensory dimensions of historical experience. It underscores the importance of auditory perception in constructing social and cultural environments. In doing so, I aim to offer a critical contribution to our understanding of the Warsaw Ghetto, illuminating the roles of sound and silence in the struggle for survival and the construction of memory in the face of atrocity.

Soundscape or soundscapes of the ghetto?

Soundscape is a term coined in 1968 by Canadian composer and music theorist R. Murray Schafer. He advocated the perception of surrounding sounds as a form of music1 and encouraged conscious and critical listening to the world as a sound environment.2 Scottish anthropologist Tim Ingold critiqued the concept of soundscapes as artificially separating aspects of the landscape into layers that are in fact inextricably linked. In his view, Shafer’s concept leads to treating sounds as objects, while according to Ingold they are rather a media for our perception. Just as light allows us to see objects, sound allows us to hear phenomena.3 Therefore, the sounds are the building blocks of experience rather than independent entities that, when combined in collections, form a specified and unambiguously describable soundscape of a particular space at a given time.

My research is guided by Schafer’s and Ingold’s understanding of soundscapes. I study the soundscapes of the Warsaw Ghetto. A critical reading of testimonies of the ghetto inhabitants allows us to decipher their sensory experiences as they recorded them in their writings, and thus to gain a better understanding of the wartime reality of Holocaust victims. I am not interested in the sounds themselves but their meaning to the contemporaries. I do not aim to present an overall sound panorama of the Warsaw Ghetto. In addition, I also do not believe it would be possible to recreate in words the sensescape of the enclosed district and a single, unequivocal answer to the question, “What did the ghetto sound like?”

Instead, I am concerned with questions of the music played in homes, entertainment venues and concert halls, the sonic aura of apartments and shelters, as well as what was heard on the streets. I use the term soundscapes to refer to the complex acoustic environments, constructed from a rich mixture of sounds, each of which contributes to the construction of an overall experience of a place at a given time and for a given person.

Perceiving soundscapes is determined by the physiology of each individual, their life experiences, and the cultural environment that has shaped them. Therefore, I am writing about many soundscapes (plural) of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Biographies

I build my research on ego-documents written by contemporaries in the ghetto, in hiding on the “Aryan” side, or in the immediate postwar years. These sources make it possible to read experiences that were still fresh in the memory of eyewitnesses. This blog is grounded in the testimonies of Ludwik Hirszfeld, Henryk Makower, Stanislaw Adler, and Adam Czerniaków, as well as the notes of Stanislaw Gombiński and Stanislaw Rożycki. They all were educated middle-aged men, belonging to the middle-class intelligentsia before the war. Except for Różycki, of whom we know little, these men were in a privileged position in the ghetto with respect to the majority of the Jewish population imprisoned there.

Ludwik Hirszfeld was a world-renowned microbiologist and serologist who had discovered the ABO blood types. In the ghetto, he organized secret training courses for doctors and pharmacists. Moreover, as chairman of the Board of Health, he worked to combat the typhus epidemic. Before the war, he lived with his family in the villa quarter of Saska Kępa in Warsaw.

Henryk Makower, a microbiologist and internal medicine physician, lived and worked in Łódź before the outbreak of war. He then moved to Warsaw, where he was forced to live in the ghetto. He became head of the infectious ward of the Bersohn and Bauman Hospital. He collaborated with Hirszfeld on the Board of Health and on secret teaching in the ghetto. The two men became close friends during this time.

Adam Czerniaków, a chemist by training, was a Jewish activist and local politician before the war. In September 1939, the Polish authorities appointed him as the commissary chairman of the Jewish community. After the capitulation of Poland, the Germans made him chairman of the Judenrat. He was a controversial figure in the ghetto, pursuing a pragmatic policy toward the Nazis and avoiding confrontation while, as far as possible, relaxing its orders. He personally got Hirszfeld involved in fighting the typhoid epidemic. Unwilling to participate in the mass deportation of Jews from the ghetto, he committed suicide on the second day of the deportation campaign, on 23 July 1942.

Stanisław Adler, born into a Warsaw merchant family, studied philosophy and law. He lived in Warsaw until the war where he built a promising legal career as an attorney. Adler fled to Lvov following the outbreak of the war but returned to Warsaw in March 1940 for personal reasons. In October, he found employment with the Jewish police as a member of its Recruitment Committee. Subsequently, he became head of the Organisational and Administrative Department. In practice, he was a legal advisor to this ghetto institution. Thanks to his position, he was perfectly familiar with the organisational dynamics of the ghetto.

Echoes of Hardship: Noise and Distress in the Warsaw Ghetto

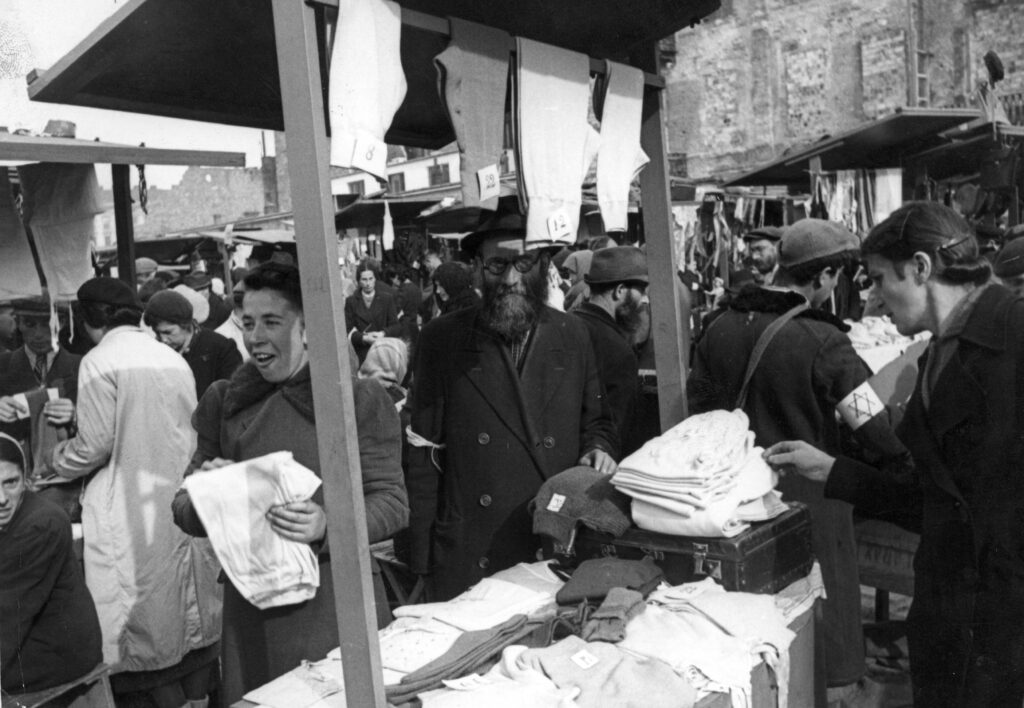

The ghetto’s congestion, pervasive poverty, and hunger drove people to its streets in search of money, alms, or just any food. The result was a constant noise, a recurring theme in numerous accounts. An outstanding physician-immunologist and a member of the (ghetto, Polish, and international) elite, Ludwik Hirszfeld initially ended up with his family in the apartment of his friends on Grzybowska Street in the small ghetto. Forced by the Germans, the move from a secluded villa with a garden came as a shock to him due to both the violence of the resettlement and the radical change of environment. Hirszfeld went from his dream home amid the “blossoming orchards of Saska Kępa”4 to a neighborhood that even before the war was among the most densely populated and built-up areas of Warsaw. After the ghetto was closed, it became even more overcrowded. He wrote: “Not only the incessant noise of the street, but the incredible scenes seen from the windows made staying there an ordeal. We did not have a moment’s rest, and our daughter became increasingly depressed.”5

Hirszfeld described the nearby area – Twarda Street and Grzybowski Square – as an abyss into hell full of “disgusting odors and screaming people.”6 Through his connections, however, he managed to obtain an apartment in a Christian enclave inside the ghetto. This place of residence gave the Hirszfeld family relative comfort that most of the residents of the “quarter” could not count on. He described that one went from the epicenter of overwhelming sensory experiences – the squeeze, noise, and stench – to the starkly different environment in which they were fortunate to live:

“(…) one entered a church courtyard that resembled the courtyards of Italian monasteries. A narrow passage, a church wall on the side, and a beautiful tall acacia tree in the courtyard. To the right behind the church were the ruins of a fantastically huge demolished house. Between the church and this house, a piece of land was torn out of the ruins and vegetables were planted. This was how life was born on the ruins. In the moonlight it looked like Pompeii, destroyed not by lava, but by human hatred. The windows of our apartment overlooked a small but lovely church garden. There is a strange charm to these church gardens surrounded by walls. We had the feeling that we were in a corner of thoughtfulness, silence, and kindness preserved in hell.”7

These were special circumstances. The majority of the inmates of the enclosed district had no chance for such living standards. Despite his privileged position and excellent and exclusive housing conditions, even the chairman of the Judenrat himself, Adam Czerniaków, suffered from the sounds of hunger and poverty. He noted on 9 June 1941: “After lunch, work at home – punctuated by the moans of beggars at the window‚ ‘bread, bread! I’m hungry! hungry!’“.8 Some two months later, he stressed with irritation the impossibility of focusing on performing professional duties under such conditions: “The scourge of the street are beggars. Among them are many professionals and children who lament monotonously without letting anyone work. In order to curb this, the Jewish Ghetto Police had set up posts. Yesterday, after lunch, I saw how a constable handles the situation. Most simply, he chases the beggars away from under my windows with handouts. This is something no policeman of any other nationality would do.“9 It is hard to imagine that in any other neighborhood the representatives of the Jewish Ghetto Police would make such zealous attempts to fight the noise as they did under the windows of the President’s apartment. While one could sometimes give one’s eyes a rest from the images of poverty, one could no longer close one’s ears to it.

An officer of the Jewish Ghetto Police, Stanislaw Gombiński wrote about the beggars’ sounds: “Their march doesn’t stop, they keep going incessantly, by the dozens, by the hundreds. They go around the houses, knock on windows, on doors, walk the streets in the evenings, after curfew, calling out in a monotonous voice: ’Hot rachmunes, Yiddish kinder, hot rachmunes! Yiddish hercer, shenkt a neduwe!’ (Have mercy, Jewish children! Jewish hearts, offer support!).”10 As the beggars were omnipresent, for the majority it was impossible to deal with them in the way Czerniakow described. Most of the ghetto inhabitants had to accustom themselves to seeing and hearing them.

Music of Respite, Music of Survival

These cries for help were not the only strategies of the destitute, deprived of work and livelihood, that manifested themselves in the soundsphere of the ghetto. Ludwig Hirszfeld’s friend and collaborator, microbiologist Henry Makower noted:”There were a lot of adult beggars, and even more children. On the corner of Żelazna and Krochmalna streets there used to be a little boy, maybe 7 years old, with a terrible squint, who endlessly repeated one and the same melody, it still sounds in my ears! However, the most popular were the ’singers’. They had one song that took the ghetto by storm, like fire flying from street to street, from yard to yard, attacking poor ears from everywhere. These children sang, or rather wailed: Oy, di bones / I don’t want to give back the ‚bones’ [ration cards].”11 “To give away ration cards” meant to die in the ghetto slang. Stanisław Adler, a lawyer and officer in the Jewish Ghetto Police, commented on this phenomenon: “As one looked at these poor, hoarse ‘singers’, one could see that they really did not want to give back the ration cards, but that unfortunately this would not help them at all. Likewise, not giving the alms did not help in any way those who could and should have given them.”12 He noted that in this and every other field, too, there is predatory competition: ”Only the one who stands out with something will raise enough.”13

The exhortations and chants of beggars, the sounds of traffic on crowded streets and the omnipresent commerce are recurring motifs in numerous survivor accounts. Still, the ghetto air was also filled with sounds that were much more harmonious. Makower recalled a first-class violinist who played on the corner of Elektoralna Street.14 He also mentioned a boy of about 16 years old “who sang Jewish and Hebrew melodies exceedingly beautifully”,15 and an older man (”You could tell by his face and demeanor that he was an intellectual”)16 who played the violin on Solna or Orla Streets while his wife collected donations at the time. Adler also wrote about philharmonic musicians who were forced to play concerts in the backyards of tenements and earn their living this way.17

Music provided ghetto residents with sustenance and respite from the grim realities of everyday life. Classical musicians and other artists found employment at, among other places, the Melody Palace, “a European-style dancehall (…) frequented by the ghetto’s rich, speculators, bribers, wheeler-dealers, those doing business with and for the Germans, smugglers, enriched gentlemen from the Jewish Ghetto Police with their damsels”,18 as Makower emphasized. He recalled that not only the rich were attending philharmonic concerts: “The tickets were quite expensive, the hall was large, almost always heavily packed. Jews like music, among the listeners one saw, next to wealthy people, a lot of poor officials, miserable youth, representatives of the proletarian world.”19 Still, it seems that only the better-off could afford this form of relaxation.

Stanisław Adler described the cultural life in his tenement house on Sienna Street which, as he emphasized, was dominated by “professional intelligentsia”20: “Almost every week gramophone concerts were held on the premises of the house, in which the most beloved virtuosos performed their showpiece numbers alongside orchestras under the baton of the best conductors.”21

From Privilege to Survival: The Role of Silence in the Warsaw Ghetto

Silence was a privilege and a luxury for both ordinary residents and the elite, as the writings of Ludwik Hirszfeld and Adam Czerniaków demonstrate. This can also be observed in the account of Stanisław Różycki, a collaborator of Oneg Sabbath of whom we know almost nothing, who stated critically that due to the German policies, streets of a Western European character had changed into an Oriental one – concurrently in visual appearance and acoustic aura.This, he wrote, gave antisemites the impetus to compare Jews to”savage Berbers”.22 Henryk Makower, on the other hand, enjoyed strolling along Sienna Street -a nice, clean, and quiet street of wealthy people where the great waves of ghetto traffic did not reach23 – and enjoyed the privileged access to the quiet and sunny terrace of the Bersohn and Bauman Hospital.24

The silence that had been craved in the earlier period became something disturbing over time, just as noise and shouting ceased to be a daily inconvenience. These sounds transformed into much more special phenomena: their decline indicated the end of the ghetto which became discernible during the deportation action (Grossaktion). Between 22 July and 24 September 1942, the ghetto population shrunk by 300,000 people, according to Jewish sources.25 People were lured with promises of a better life, caught in roundups in the streets or forcibly taken from their homes and led to the Umschlagplatz (Collection Point), where they were later transported by trains to annihilation camps – mainly to Treblinka.

Numerous authors, including Henryk Makower, described how the streets sounded at that time. One could hear the shots and screams of soldiers, the barking of dogs, yet the population of the “district” was surprisingly quiet: “(…) there were daily blockades in the ‘cauldron’ area, often involving dogs. Street after street, house after house were swept through. Shots were constantly heard, groups of captured people were constantly carried out to the Umschlag. Outside the ‘cauldron’, however, it was quiet, blockades were not made. Only at night did a lot of soldiers roam around, robbing whatever they could under the pretext of a leaky blackout or even without pretext.”26

The previously noisy crowds, preoccupied with the struggle for survival disappeared. Their silence was an expression of surrender to the ruthless Nazi violence: “The large crowd, lined up on the street in fours, waited in eerie silence for their fate. At first, the SS on the spot inspected the certificates: those with good ones went to one side and then to ‘freedom’, those with bad or no certificates went to the other side and to the Umschlag. But very often the Ausweise and work permits were disregarded, and selections were made by the staff by eye. Whoever they liked won temporarily, whoever did not went to his death. These were incredible, horrible scenes. Complete silence, thousands of resigned people and a handful of masters of life and death. No hint of rebellion, no struggle, no attempt to break out,” as Makower wrote.27

Depopulated by the Germans, the ghetto became empty and quiet – the absence of the cacophony of everyday life, apart from the obvious sights of the streets, was the clearest indication of the scale of the deportation. Previously crowded and bustling places remained dead most of the day, such as the corner of Leszno and Żelazna Streets. These sites only became alive in the mornings and evenings, when organised groups of Jews working outside the ghetto passed through that area.28

At the next stage, the final period of the “residual ghetto”, silence became a matter of life and death. The remaining residents of the “district” were already fully aware that they would not survive other than by fleeing to “the other side” or by hiding from round-ups in specially prepared shelters. Those in the latter situation had to maintain complete silence so as not to draw the attention of the Nazis searching the buildings. The slightest noise could bring death to anyone in hiding. For this reason, silence was ruthlessly enforced on everyone – regardless of age or health. Stanisław Adler described this type of event as follows:”During the ‘resettlement action’ shelters were sometimes discovered as a result of the irresponsible behavior of just one person. In the aftermath, there were incidents of poisoning of the mentally ill and killing of the wounded who moaned too loudly. There was a story about a mother suffocating her child, and thus saving others and herself. R[osa) Z[ajtman) was strangled in a storage room when she began to scream in terror at the sight of an approaching Ukrainian. For the safety of the general public and for fear of a criminal backlash, we propose a gardenal for parents of screaming children.”29 Thus, silence has ceased to be a luxury and became a prerequisite for survival.

Sound in Holocaust Narratives and Memory

The analysis of sound as a tool to understand the horrors of the Shoah has gradually been recognised in past years across different fields.30 Although we cannot hear the sounds of the Warsaw ghetto as its prisoners did, we can investigate their writings in search for their sonic insights, which allows us to better understand their experiences and the Holocaust in general.

Through critically examining the sounds of the Warsaw Ghetto, this article has ventured into an exploration of how sound, music, noise, and silence were not merely background elements but active constituents of the embodied experience of ghetto life. The auditory experiences of the ghetto, as drawn from personal testimonies, illustrate a dynamic acoustic environment where sound served as a medium of identity, social stratification, personal resistance, and survival. From the incessant noise of overcrowded streets to the strategic silences during deportations and roundups, the inhabitants of the Warsaw Ghetto navigated a complex sonic landscape that shaped their perceptions and experiences of confinement. Music emerged as a poignant element of this soundscape, offering solace and a semblance of normality amid chaos. In addition, it served both to uplift spirits and as a grim reminder of prewar life and the ongoing Nazi atrocities.

Furthermore, the investigation into the ghetto’s soundscape underscores the broader implications of sound in understanding social and cultural dynamics under oppressive regimes. It reveals that soundscapes can function as powerful indicators of community resilience and the human condition, as well as it reflects the social hierarchy among the ghetto inhabitants.

This article contributes to Holocaust studies and enhances the interdisciplinary dialogue between history, anthropology, and acoustic ecology. By delving into the sensory dimensions of historical experiences, it enriches our understanding of how profoundly sound and silence can impact human lives, particularly in contexts marked by extreme persecution and violence. Thus, it calls for a deeper engagement with the sensory histories of past events to gain a fuller appreciation of their complexity and lasting impact on individual and collective memories.

- Schafer, R. Murray (1969). The New Soundscape: A Handbook for the Modern Music Teacher. New York: Associated Music Publishers, p. 5-6. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 49. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 11. ↩

- Hirszfeld, L. (1957). Historia jednego życia. (Wydanie II.), p. 157. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 253. ↩

- Ibidem. ↩

- Ibidem. ↩

- Fuks M. (Ed.) (1983), Adama Czerniakowa dziennik getta warszawskiego, Warszawa: PIW, p. 191. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 202. ↩

- Gombiński (Mawult) S. (J.) (2012), Wspomnienia policjanta z getta warszawskiego, Warszawa, p. 47. ↩

- Makower H., op.cit., p. 199. ↩

- Adler, S. (2018). Żadna blaga, Żadne kłamstwo…, Warszawa: Biblioteka Świadectw Zagłady, p. 199-200. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 85. ↩

- Makower H., op.cit., p. 199. ↩

- Ibidem. ↩

- Ibidem. ↩

- Adler, S., op. cit., p. 289-290. ↩

- Makower H., op. Cit., p. 196. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 196-197. ↩

- Adler, S., op. cit., p. 104. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 107. ↩

- Różycki S., Obrazy getta (in:) Archiwum Ringelbluma t. V, Getto Warszawskie. Życie codzienne, p. 30. ↩

- Makower H., op. Cit., p. 176. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 177. ↩

- Engelking B., Leociak J. Getto warszawskie. Przewodnik po nieistniejącym mieście, Warszawa 2013, p. 753. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 131. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 68. ↩

- Ibidem, p. 185. ↩

- Adler, S., op. cit., p. 374-375. ↩

- The film “Son of Saul” serves as an excellent example of operating with auditory means of narration. In the movie, the sound environment within the Auschwitz concentration camp provides a visceral, immersive experience for the viewers. The film’s use of diegetic sound serves to authenticate the setting and to envelop the viewer in the protagonist’s journey, making the auditory cues central to the narrative. Similarly, Jonathan Glazer in “The Zone of Interest” employed a meticulously crafted soundscape to make present what the visuals deliberately obscured.The curators of the “Around Us a Sea of Fire” exhibition in Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, on the other hand, used soundscapes as an integral part of the exhibition. They chose to tell a story about civilians’ perspective of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising with exhibition architecture, photographs, maps and texts, as well as with fragments of original diaries from the ghetto read by actors, accompanied with music “inspired by 11-year old pianist who died of pneumonia in a hideout on the ‘Aryan’ side on the third day of the Uprising”. Those are valuable examples of contemporary sound design used as narrative tool for depicting Holocaust in a more comprehensive manner to the modern audience. ↩