For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

First of all, let me start with a historical digression, by way of introduction. At the start of the German-Soviet war, Galicia was occupied by Nazi Germany. In the first days of the occupation, a wave of anti-Jewish violence took place in the cities, shortly after which all anti-Jewish laws entered into force on the territory of the Governor-General Hans Frank. The first ghettos were created in the cities and towns of Galicia. The resettlement of Jews to ghettos was accompanied by plundering and confiscation of Jewish property. After the ghettos were created, the most pressing issue for Jews was the question of labor. The Germans established a structure in which the guarantee of life for Jews was work at enterprises and documents certifying this. People who did not have appropriate job documents were targeted in “actions” that the Germans conducted periodically. Those detained were shot or deported to the Belzec death camp.1

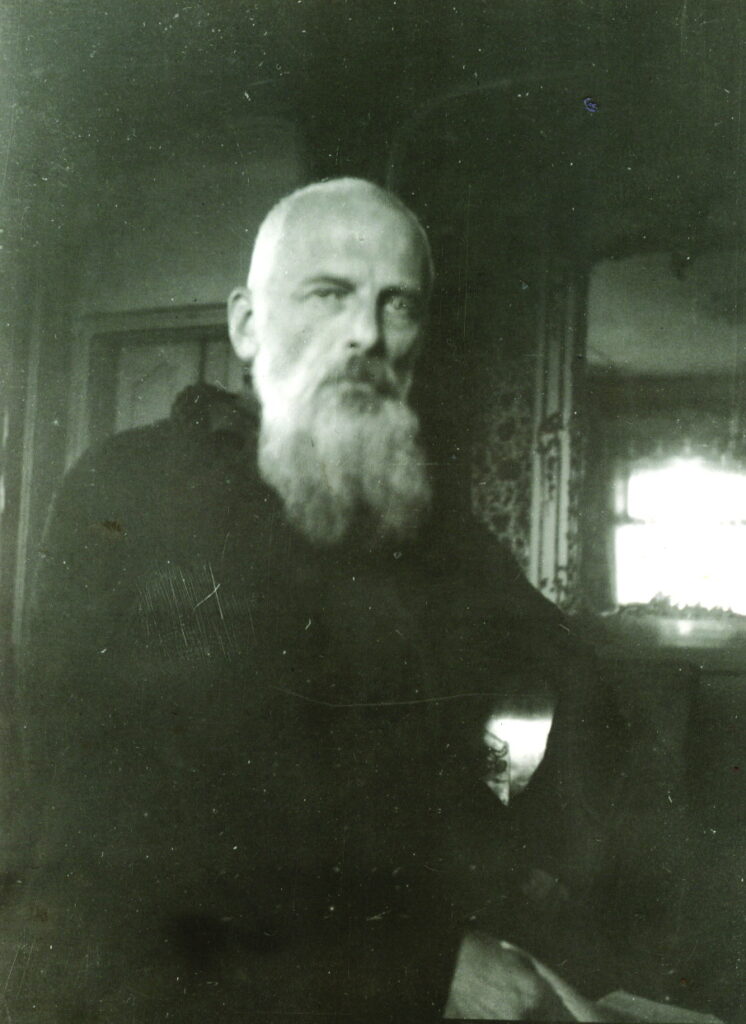

From the first days of the occupation, the head of the Greek Catholic Church, Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky (1865-1944), to the best of his ability, tried to counteract the violence that befell the Jews. Initially, he did so by means of pastoral messages to Ukrainians who belonged to the Church he led. In these messages, he gave his followers moral and practical guidance on how to act in the face of growing evil. The pinnacle of this was the message “Thou Shalt not Kill” of November 21, 1942.2

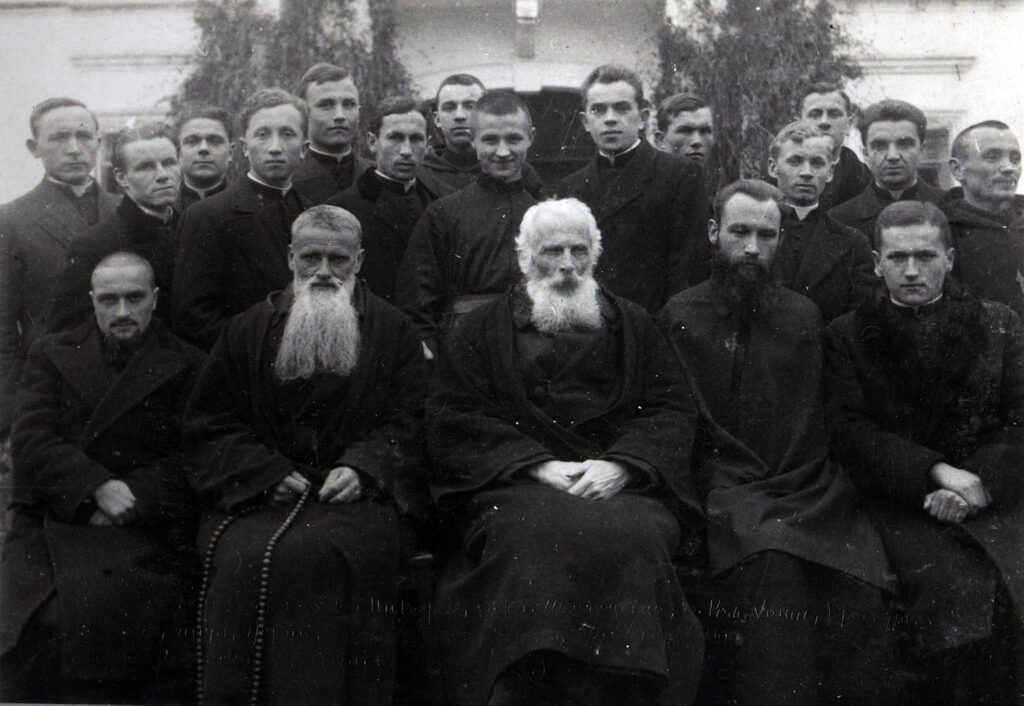

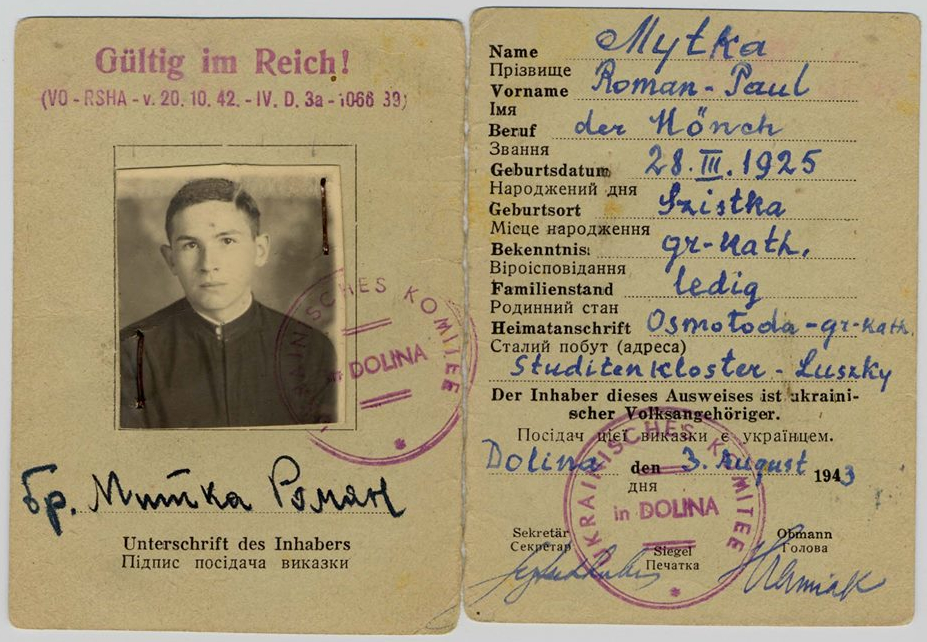

The turning point that brought Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky to a new level of resistance and assistance to the Jews was the August 1942 operation in Lviv. A number of Jews from the Lviv ghetto approached the head of the GCC with the request to hide them. The Metropolitan agreed to this. Thus began the rescue operation. The coordinators were the abbot of the Univ Holy Dormition Lavra of the Studite Rule, Hieromonk Klymentii (Kazymyr Sheptytsky, 1869-1951) and the abbess of the Holy Protection Monastery of the Studite Rule, Mother Iosyfa (Olena Viter, 1904-1988). First, the Studites began to rescue children, later they would help adults, too. The main places of refuge were the orphanages at the St. Ivan’s and Holy Dormition Lavras, the Holy Protection Monastery, and the orphanages of the Studite sisters in Briukhovychi and Lviv. People were also hidden in the monastery of St. Josaphat in Lviv, which belonged to the Studites, in parishes served by Studites or clerics related to them through family ties, and in daughter houses of the Studite sisters.3 As a result, we can say that a whole system of locations and involved actors took shape.4

In parallel to this initiative of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, situational assistance to Jews developed. The Studites who hid Jews passed on to them by Sheptytsky’s group also hid Jews who approached them outside of this initiative. Examples of this are cases from the Univ Holy Dormition Lavra (the story of Adam Daniel Rotfeld) and the Solid shoe factory in Lviv.5 This factory, located at 16 Trybunalska St., was owned by the Studion company, which in turn belonged to the Lviv Archdiocese of the Greek Catholic Church. The director and founder of this enterprise was Hieromonk Ioan (Jozef Peters, 1905-1995), who founded it in the fall of 1941. Its workers were both laymen and monks of the Studite Order, to which Father Ioan (Peters) belonged. The produce went to the Wehrmacht, the profits were intended for projects of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. The head of the GCC used these funds to support his entourage and directed them to the needs of Jews, whom he began actively rescuing in the summer of 1942. Soon, the factory became one of the locations in Lviv where the Studites hid people. Hiding could be either stationary or transitional – until a more reliable shelter was found. In order to streamline the process, well-trusted women were engaged in preparing food, after which the monks would take the packages and hand them over to the Jews hiding at the Solid factory. Among the survivors, the Fink family (consisting of four people) left the most extensive testimonies about the factory. Due to the constant threat of exposure, they were gradually separated. The children had to hide separately from adults. This family faced manifold adversities – illness of the daughters, moving to a new location, and the inconvenience of their shelters. But in the end, the whole family survived. Three of their main rescuers from the Solida factory would receive the title of Righteous Among the Nations.6

Situational assistance and shelter were provided by various priests and monks of the Order of St. Basil the Great and the Order of the Most Holy Redeemer. In particular, the hegumen of the Holy Dormition Monastery, Hieromonk Vasylii Velychkovsky (1903-1973), provided active support to Jews in Ternopil. In doing so, he sought active cooperation with the Sisters Servants of the Immaculate Virgin Mary.7

The greatest contribution to the hiding of Jews in the territory of the Galician Metropolis was made by women’s congregations. To be specific, the Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Family, the Congregation of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent Paul, the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, the Society of Sisters of St. Josaphat, the Congregation of Sisters Servants of the Immaculate Virgin Mary, monasteries of the Studite Rule, monasteries of the Order of St. Basil the Great. These Orders and Congregations already oversaw an impressive system of orphanages before the war (to grasp its scale, it suffices to glance at the yearbooks of the Archdiocese during the interwar period). During the Holocaust, these orphanages provided both situational assistance and some of their representatives joined the initiative of Metropolitan Sheptytsky. Most of the children they saved were Jewish. One of the best examples of this is the orphanage of the Sisters of the Servants in Przemyśl.8

A question that still provokes both debate and speculation is the number of those rescued. As of the moment of writing this text, it is impossible to indicate a number based on the available source material. The reason is the secretive measures undertaken by the rescuers. From what I know, no records were kept about the reception of people, their names, and so on. However, there is reason to believe this issue might yet be cleared. After the end of the German occupation, according to the testimonies of surviving Jews rescued by Sheptytsky’s group, a list of about 150 survivors was compiled. Another such list was compiled of Jews rescued with the participation of Mother Iosyfa (Viter). It used to be part of the criminal case conducted against her by the Soviet state security apparatus. However, these documents are presently missing from the archives. Perhaps someone will find them someday and they will become a valuable source to answer the question of how many people were rescued. As for my research, I identified 19 Jews rescued by Studite monks and 7 Jews rescued by Studite nuns. Moreover, I identified 29 Studite monks who participated in the rescue of Jews. These data are not final and reflect the state of research at the time of publication of my monograph in 2019.9

The Source Base

During my postgraduate studies, I soon realized that I had set myself a very difficult task in terms of available source material. Still, by gradually working through various archival collections, I managed to overcome this challenge. As of today, a researcher who wants to study this topic should pay attention to the materials stored in the following source bases: the Archive of the Institute of Church History of the Ukrainian Catholic University; the Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center; the Archive of the Univ Holy Dormition Lavra of the Studite Rule; the Archive of the Sisters Servants of the Province of the Compassion of the Mother of God in Ukraine; the Branch State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine; the Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine, Lviv; Archive of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw; the USC Shoah Foundation Institute’s Visual History Archive; the State Archive in Przemyśl, Poland; the Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine Office in Lviv Oblast; the Lviv Oblast State Archive; the Arolsen Archives; the International Center on Nazi Persecution; the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) Archives.

Useful materials available in these archives can be divided into three groups:

1) Information about the context of events. It is important to consider how the monasteries fared before World War II and how they developed. This is best reflected in the collections of the Central State Historical Archive of Ukraine, Lviv. In particular, attention should be paid to fonds 201, 377, 408, 409, 525, 577, 684, and especially to fond 358 – concerning Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky.

2) Information about the rescued. Valuable sources are the testimonies and interviews stored in the Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, the Archive of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, The USC Shoah Foundation Institute’s Visual History Archive, and the USHMM Archives. Working through these materials, it is even possible to trace which aspects survivors of various ages highlighted when describing rescuers and circumstances of rescue. Examples of this are the cases of Lili Pohlmann-Stern (1930-2021) and Sister Maria (Faina Liakher, 1917-2005). Lili Pohlmann gave the first testimony about her experiences in 1945 in Krakow to representatives of the Central Jewish Historical Commission10 and the last one in 2016.11 Sister Maria (Liakher) wrote down her first testimony in 194812 and gave her last interview in 2001.13

Contributions by individual survivors are also of interest. Kurt Levin (1925-2014), the son of the Lviv rabbi Ezekiel Levin (1897-1941), stands out in this regard. He and his brother Nathan (born 1932) were saved by Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. After the war, Levin wrote his first memoir Przeżyłem. Saga Świętego Jura spisana w roku 1946 (I Survived. The Saga of Saint Jura Written in 1946).14 Later he would write Journey through Illusions as a summary of his career and life.15 Together with the memoirs of Rabbi David Kahane (1903-1998), Diary of the Lviv Ghetto,16 These books are key sources for understanding the scale, participants, methods, and dangers of sheltering Jews during the rescue operation of the Head of the GCC. In fact, Kurt Levin not only described his own experiences but spent his whole life collecting testimonies and documents about the hiding of Jews by the Metropolitan’s entourage. This endeavor resulted in a collection which is now stored in the USHMM Archives (copies of it were transferred to various archives by Kurt Levin himself).

The vast majority of sources from various archives were collected in the context of the recognition procedure revolving around the issue of whether Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky should be granted the title of Righteous Among the Nations. As a matter of fact, this process has been a determining factor for preserving the memory of the rescue of Jews by the clergy and monastics of the Greek Catholic Church.

It began on May 5, 1964, when Rabbi David Kahane spoke at a meeting of the Commission at the National Institute of Holocaust Remembrance and Heroism of Yad Vashem with a proposal to confer the title of Righteous on the Metropolitan. Another hearing was held the same year, but during the third hearing on December 12, 1967, Eliyahu Yones (1915-2011), a member of the commission, raised doubts with the chairman of the commission, Moshe Landau (1912-2011). Subsequently, the case entered a state of debate that continues to this day. Over the years, the commission has met 12 times years regarding the Metropolitan. The last such occasion was in 2012.17

Jews rescued by Metropolitan Andrei actively participated in the discussion. Their testimonies are stored both in the Yad Vashem Archive and in the USHMM Archives.

Despite the fact that the case of the Head of the GCC remains unresolved, his closest associates have already received this title. There are 1 nun and 6 monks of the Studite Order.

3) Information about the rescuers. The largest pool of information is stored in church archives. It should be said at once that these archives began to take shape in the 1990s with the emergence of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church from the underground and the re-establishment of monasteries. The richness of these archives is striking, but when it comes to World War II, they exhibit one peculiarity. Since 1989, historians of the Church in Ukraine, as well as the leaders of the Congregations and Orders, have focused most of their attention on unravelling and preserving the memory of the persecution of the Church by the communist regime, studying the phenomenon of active religious life within the totalitarian reality of the Soviet Union. Therefore, the topic of resistance to the national socialist regime has remained secondary. This asymmetry is reflected by the collections of interviews with clergy and monastics in the Archive of the Institute of Church History of the Ukrainian Catholic University. It can also be observed in the Archive of the Univ Holy Dormition Monastery of the Studite Rule, the Archive of the Sisters Servants of the Province of the Compassion of the Mother of God in Ukraine.

Some autobiographical information can be retrieved from the postwar criminal cases conducted by the Soviet state security agencies against the clergy and monastics of the GCC. These are stored in the Branch State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine and the Archive of the Office of the Security Service of Ukraine in the Lviv region. However, working with these files requires highly critical scrutiny and a profound understanding of the contexts, in view of the falsifications, distortions and additions made by the employees of the punitive structures in order to prove the guilt of the prisoners.

In addition to documents stored in various institutions, the experience of interviews with witnesses of the events, as well as with their relatives, acquaintances, brothers and other people, proved highly valuable for me. Sometimes it was the only available option to clarify past events. Such interviews allowed me, for example, to research the circumstances under which Jews were rescued in the village of Univ and neighboring villages. This helped me better understand the sheltering of people in the Univ Holy Dormition Studite Lavra.

Prospects for Research

In my opinion, historians in Ukraine are still in the early stages of researching the rescue of Jews by the clergy and monastics of the GCC during the Holocaust. There are still many blank pages that require our attention.

In August 2022, I, together with fellow researchers from Lviv and Kyiv, created the NGO Eastern Catholic Churches History Study Center 18. The purpose of our organization is to unite researchers of the history of the Eastern Catholic Churches with the aim of exchanging experiences, writing joint studies and popularizing the topic in the scientific world. In the near future, we plan to initiate a project that will show how different Eastern Catholic Churches under the German occupation reacted to the Holocaust.

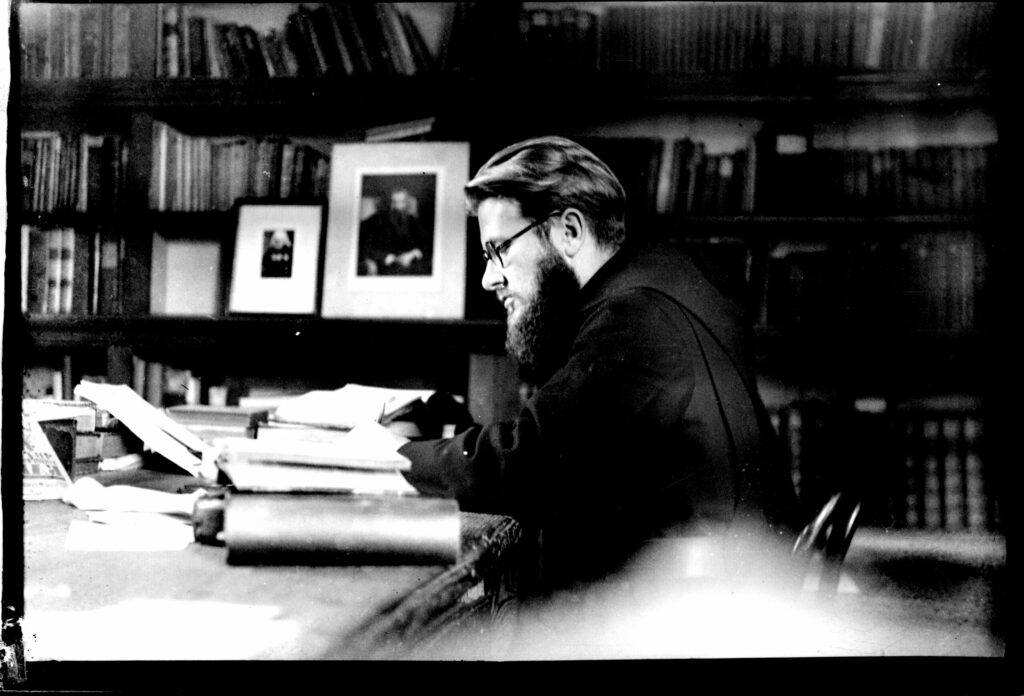

As for my research: despite the war, I continue to work actively. I received a Ukrainian Emergency Scholarship from the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture (2022) and Research Stipend for Mandel Center Alumni of the Ukrainian Summer Programs (The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, 2023), which allowed me to complete the monograph, titled Solid: The Shoe Factory of Life, and prepare it for publication. The book will be about the hiding of Jews by Studites at their Lviv shoe factory Solid in 1942-1944. The only thing I would still like to do in this direction is to publish the writings of the monks and nuns of the Studite Charter recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. In 2020, I published the writings of the Righteous Among the Nations Hieromonk Daniil (Dmytro Tymchyna, 1900-1972).19 But there are still other sources that beg to be processed and published. Moreover, I am shifting my focus to the rescue of Jews by women’s congregations during the Holocaust.

In this vein, I have already begun working on my next project, Prayer and Violence: Greek Catholic Nuns and the Holocaust, made possible by a Fellowship of the Shevchenko Emergency Fund (The Shevchenko Scientific Society in the U.S., 2022) and Research Stipend for the IU-Ukraine Nonresidential Scholars Program (R.F. Byrnes Russian and East European Institute, Indiana University, 2023).

My first cursory research on this topic dates back to 2019 when I was one of the co-organizers of the International Academic Conference Dedicated to the 100th Anniversary of the Passing of the Venerable Mother Josaphata Hordashevska.20 Back then, I wrote an article titled “A Forgotten Page of Human Help: The Congregation of the Servant Sisters of the Immaculate Virgin Mary and the Holocaust”.21 My work on this article made it clear to me that the topic is under-studied, complex and requires elucidation. Gathering sources on this topic is more complicated than, for example, in case of the Studites. But there are several key historical figures (Mother Iosyfa Viter, Monika Polianska, etc.) who offer starting points. A number of survivors have also been identified (Faiga and Anna Fink, Lili Pohlmann, with whom I had the pleasure of corresponding, and others). I think that this work will be an important link in filling so far understudied aspects of Ukrainian history of World War II. After all, to this day, there is no work uncovering the female side of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky’s designs.

In the future, I would also like to write a reference work, The Greek Catholic Church and the Holocaust: Lines of Resistance and Rescue. In this study, I would like to answer three research questions: how resistance to the Holocaust spread among the clergy, monastics and episcopate of the GCC; how the situational and organized rescue of Jews by representatives of the clergy and monastics developed; how the historical memory of these events was formed.

In broader terms, I think that in the coming years, historians of the Ukrainian GCC will focus on processing collections from the Vatican archives that cover the period of the pontificate of Pius XII (1939-1958).22 I believe that the introduction of new source materials from these collections will allow for a deeper understanding of the final years of Metropolitan Andrei’s activity. In 1912, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky established the Historical and Ecclesiastical Mission in Rome to research, catalogue and copy documents from the Vatican archives and public libraries in order to accumulate a source base on the history of the Ukrainian Church. I believe the present-day Ukrainian GCC needs to continue this work in the light of new opportunities.

This could also prove to be a new impetus to the recognition of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky as the Righteous Among the Nations. In this matter, regardless of possible findings in the Vatican archives, we still have a long way to go. First of all, based on the experience of previous decades, it is necessary to develop an “action plan”. This requires combined efforts of the GCC, the Ukrainian state and the Ukrainian academic community. I think it would be a good idea to start the practice of round tables between Ukrainian and Israeli historians to discuss pressing issues of the past. It would even be possible to create a joint historical commission with a separate chapter devoted to the case of Metropolitan Sheptytsky. In my opinion, only step-by-step work on the historical dialogue between Ukraine and Israel will be able to bring progress in this case, as well as many others.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Tobias Wals

- https://zbruc.eu/node/76461 ↩

- http://www.ji.lviv.ua/n28texts/ne-ubyj.htm ↩

- https://synod.ugcc.ua/data/proty-techiy-yak-ukraynski-monahy-studyty-vreyv-ryatuvaly-3688/; https://www.vaticannews.va/uk/church/news/2020-09/urok-lyudyanosti-yurij-skira-pro-ryatuvannya-yevreyiv-studytamy.html ↩

- Skira Iu., Poklykani: MonakhyStudiis’kohoUstavutaHolokost(Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2019), 53-61. ↩

- Skira Iu. P., “Perekhovuvannia ievreïv monakhamy Studiis’koho Ustavu na vzuttievii fabrytsi ‘Solid’ u L’vovi v 1942-1944 rr.”, Naukovyizhurnal “Istoryko-kul’turnistudiï”, 2016, No. 1 (3), 113-117. ↩

- https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/en/he-is-our-ukrainian-schindler-yuriy-skira-on-the-monks-who-rescued-jews-during-the-holocaust/ ↩

- Skira Iu., “Zabuta storinka liuds’koï dopomohy: Zhromadzhennia sester sluzhebnyts’ Neporochnoï Divy Mariï i Holokost”, MaterialyMizhnarodnoï naukovoï konferentsiï do 100-littiaviddniaperekhodudovichnostiPrepodobnoï MateriIosafatyHordashevs’koï (Lviv: KnyhoVyr, 2019), 47-67. ↩

- http://archiwum.polradio.pl/5/123/Artykul/296283 ↩

- Skira Iu., Poklykani: MonakhyStudiis’kohoUstavutaHolokost(Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2019), 253-256. ↩

- Relacje ocalonych z Zaglady. Stern Lilith. Archiwum żydowskiego instytutu historycznego w Warczawie. Z. 301. T. 1181. 18 s. ↩

- Skita Iu., “Poriatunok rodyny Shtern mytropolytom Andreiem Sheptyts’kym u svitli spohadiv Lili Pol’man”, VisnykKyïvs’kohonational’nohouniversytetuim. T. Shevchenka, 2017, vyp. 2 (133), 68-70. ↩

- Sister Mariia (Liakher), “Nekhai slavyts’sia im’ia Mariï!”, Velykoprepodobnomu Ottsiu Ihumenu, Naidorozhchomu moiomu Dukhovnomu Bat’kovi, 1. August 1948, Archive of the Univ Holy Dormition Lavra, f. 15, op. 1, spr. 43, t. 1 (14 ark.). ↩

- Interview with sister Mariia (Liakher), Studite nun, 2 February 2001, Lviv, conducted by brother Irynei-Ivan Voloshyn, Archive of the Institute of Church History at the Ukrainian Catholic University, f. P-1, op. 1, spr. 743.10 (16 ark.). ↩

- Lewin K. Przeżyłem. Saga Świętego Jura spisana w roku 1946. Warszawa: Fundacja Zeszytów Literackich, 2011. 188 s. ↩

- Levin K., Mandrivkakriz’ iliuziï (Lviv: Svichado, 2007). ↩

- ShchodennykL’vivs’kohohetto. SpohadyrabynaDavydaKakhane(Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2003). ↩

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VQxPFDfL6XA ↩

- https://opendatabot.ua/c/44785479; https://www.facebook.com/ecchsc ↩

- https://svichado.com/svyati_i_vyznachni_postati/postati/ya-dlya-vas-gotoviy-i-jittya-viddati—-tvori-pravednika-narodiv-svitu-iyeromonaha-daniyila-(timchini)- ↩

- https://synod.ugcc.ua/data/stala-vidoma-programa-konferentsiy-do-100-richchya-vid-dnya-smerti-prepodobnoy-yosafaty-gordashevskoy-611/ ↩

- Skira Iu., “Zabuta storinka liuds’koï dopomohy: Zhromadzhennia sester sluzhebnyts’ Neporochnoï Divy Mariï i Holokost”, MaterialyMizhnarodnoï naukovoï konferentsiï do 100-littiaviddniaperekhodudovichnostiPrepodobnoï MateriIosafatyHordashevs’koï (Lviv: KnyhoVyr, 2019), 47-67. ↩

- Athanasius D. McVay Vatican Archives and Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky: Discoveries and Future Perspectives. Presentations from the International academic online conference dedicated to the 155th anniversary of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptyskys birth / compiled by Yuriy Skira, edited by Hanna Dydyk-Meush. Lviv: Koleso, 2021. 195-205 pp. ↩