Introduction

“We all have a duty to fulfil towards our past,” implored Dr Eva Reichmann, former Director of Research at The Wiener Library, in a short front-page appeal in the journal of Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain in 1954. Reichmann’s impassioned article launched the Library’s ambitious effort in the mid-1950s to record testimonies about the Holocaust, a project that would successfully gather more than 1,300 reports in seven different languages over the following seven years.

The Wiener Library was founded by Dr Alfred Wiener, a German Jewish intellectual who campaigned from 1919 to alert German society to the threat of impending Nazism. He collected materials about and disseminated warnings against the dangers of antisemitic extremism. Wiener moved the collection, formed by the creation of the Library’s predecessor organisation, the Jewish Central Information Office (JCIO), to Amsterdam in 1933 and then to London in 1939. The British government used Wiener’s collection to inform its intelligence on Nazi Germany, and then after the war, for the prosecution of Nazi criminals at Nuremberg.

The Wiener Library became a unique forum for the study of Nazism as the fledging field of study emerged along with the remnants of documentary evidence.

The 1950s testimonies project grew out of these efforts, but turned in a concerted way to the perspectives and experiences of the victims. Over a period of about seven years, and with financial support from The Conference on Jewish Material Claims against Germany, Reichmann and her team gathered reports from refugees and survivors in Britain and abroad. The interviewees recounted their experiences of events from 1933 through the end of the war as well as its aftermath. Calls for interviewees were issued in the British and continental European press, and many were found through networking and word-of-mouth, as the example below indicates. Trained interviewers – many of whom were often survivors or spouses of survivors – recorded, transcribed, edited and indexed the accounts under Reichmann’s direction. In addition to survivors’ testimonies, the collection also includes contemporary documents and letters.

Visualising Methodology in the Testimonies

Taking a close look at the reports themselves reveals fascinating aspects of the methodology Reichmann and her associates used in gathering the testimonies. By visually annotating one example, we can see the different layers of interaction that the Library had with the survivor and her narrative during the duration of the project, and suggests details about the process in which the reports were collected and introduced into the Library’s collection. The annotations and the methodology embed The Wiener Library’s testimonies project within the historiography of historical commissions after the war and the long tradition of Khurbn-forschung (See, for example, Laura Jockusch, Collect and Record!).

The annotations visually represent different layers of mediation and bring attention to the textuality of the document.

While the provenance of each testimony is still being traced in correspondence held in The Wiener Library’s institutional archives (which is in the process of being catalogued) and other sources, we have established that Reichmann led a small group (of at least four-five) paid staff members to collect reports from survivors, with interviewers located throughout Europe involved in tracing, contacting and persuading potential interviewees to take part.

The project began in the mid-1950s and continued on until the 1960s, proceeding in a concentric and centrifugal direction: they started close to London and gradually spun out further and further as the network of interviewers and interviewees widened. The methods were described in The Wiener Library Bulletin in autumn 1955:

Only occasionally the reports will be drawn up by the authors themselves; usually the eye witnesses are visited by one of the Library’s interviewers for one or more conversations. During these the interviewer tries to elicit as much information as possible and, on the strength of it, writes the report. This is submitted to the interviewed person to ensure that it contains no mistake or misunderstanding, and is subsequently incorporated into our archives. For the purposes of reference, it is analysed, catalogued and cross-indexed.

The visual annotations below reveal Reichmann’s consideration for the veracity of the specific details of the testimony and her goal to convey historical ‘truth’ – a practice that may seem surprising in relation to later methodologies of recording testimonies (Wievorka, Era of the Witness). In later decades, testimony projects tend to keep for posterity on film or audio the exact words of the survivor without further editing, even where information (such as dates or place names) may be inaccurate or uncorroborated. It is clear from correspondence among the team working with Reichmann that they returned frequently to an individual to clarify and corroborate particular aspects of their stories, and in some cases, the information was not verifiable and the testimony possibly excluded from the collection. The individual was then asked to sign the updated report.

At the same time, correspondence indicates that Reichmann and her colleagues tried to preserve as much as possible the character and meaning of the author of the report, particularly where they could not verify particular details or were unclear about certain forms of expression, especially for those who were writing in German but whose first language may have been something else.

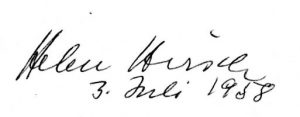

The interview annotated below illustrates the methodology effectively. The report was submitted in July 1958 and was provided by Mrs Helen Hirsch (née Meyer), originally from Teplitz-Schönau (Teplice-Šanov, in Czech). Nelly Wolffheim, a German Jewish expert on psychoanalytic pedagogy and early childhood development and who fled Nazi Germany to London in 1939, recorded the report. This was one of 35 such reports Wolffheim contributed to the project.

Click on a highlighted element of the text below to learn more.

See fullscreen visualisation of the Annotated Interview with Helen Hirsch, page 1

See fullscreen visualisation of the Annotated Interview with Helen Hirsch, page 3

Annotation of the documents was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

Please follow the links for a full collection description in The Wiener Library Collections Catalogue, as well as the full original text and translation of the document:

Wiener Library catalogue description: Eyewitness reports regarding the November Pogrom

Omeka description, scan of original document, transcription and English translation: Gestapo insists on divorce of a mixed marriage

Supporting Documentation and Verification

The correspondence in The Wiener Library shows that Reichmann paid closed attention to the veracity of details and themes in the reports, and understood the individuality and particularity of each report, but also the report’s place within the larger collection of testimonies and the Library’s collections as a whole. One can assume that most of the adjustments were done by Reichmann’s own hand, but it is interesting to note that these marked up reports were the final versions left in the record – i.e., at least some of the typed reports with handwritten annotations were not re-typed before they were acquisitioned into the collection. The extent to which multiple versions, or at least annotated versions, are kept within the testimonies collection requires further research.

Here we can see that although the report was not written in the first person by Hirsch, she signed off on the changes that were made to the document. This verification was part of the acquisition process for the testimonies.

The annotations are thus invaluable for unlocking clues about the methodology of the project, the motivations of the interviewer and the interviewee, as well as the original words of the survivor – whether ‘accurate’ or not. As noted above in the visualisation, the report by Helen Hirsch was recorded in the third-person, authored and arguably, further mediated by the interviewer, Nelly Wolffheim. In this and other interviews conducted by Wolffheim, it is sometimes difficult to determine where the voice and intentions of the interviewer has superseded that of the interviewee. Visualisation of the changes made to the report, coupled with close analysis of related correspondence, may reveal further insight.

Digital Testimonies

Finally, the visual annotation raises important considerations about the historical value of versions, and what is potentially lost in the process of digitisation if multiple iterations of a digital document are not preserved.

As this discussion shows, visualisation and digitisation often (and should) raise more questions and prompt further analysis, using both digital humanities and more ‘traditional’ research methods. Further questions for consideration include:

-

- How does an understanding of the particular methodology of the project, the history of the Library and key individuals involved, and the collections strategy at the time helps us read the testimony?

- To what extent do the annotations and different versions of the testimony need to be preserved within the historical record (and thereby any online publication of the source)?

- How does visualisation draw attention to and raise further questions about the roles of the interviewer and editor in the process of transmitting memory?

- How do we preserve the individual and unique voice of survivor(s) involved in each report?

- And finally, what is lost if a testimony, such as this one, is published out of context and separately from the collection for which it was recorded?

The testimonies form the basis of a major digitisation initiative The Wiener Library is currently undertaking, titled Testifying to the Truth. A planned web resource will be published in 2018 featuring the translated testimonies, as well as supporting research from the Library’s other collections. The Library aims to make these rare testimonies accessible to students, researchers and scholars.

With special thanks to Jessica Green and Wolfgang Schellenbacher for the visualisation, Torsten Jügl for help navigating The Wiener Library archive, and Shoshanah Hoffman for the translation of the testimony.

Sources

- Jockusch, Laura. Collect and Record! Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe (Oxford UP, 2012).

- Kerl-Wienecke, Astrid. “Nelly Wolffheim.” Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. 1 March 2009. Jewish Women’s Archive. (Accessed on January 7, 2018) <https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/wolffheim-nelly>.

- Wievorka, Annette. The Era of the Witness (Cornell UP, 2006).

- Wiener Library Archives 70