For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

The Babi Yar tract in Kyiv is well-known as a site of murder and burial of Holocaust victims. During the Second World War, it was located on the outskirts of the city; now, it is part of the urban metropolis. In the Ukrainian intellectual community, Babi Yar has long been not only an object of memory, but also a subject of reflection, reminiscence, and scientific research. The location of the mass extermination of Jews of Kyiv was even known during the Second World War. The first information about the victims appeared in November of 1941 in the Izvestiya newspaper (which included references to US news agencies). At the time, the publication spoke of the more than fifty thousand killed. Between 1943 and 1945, in Penza, Moscow, and Kyiv, the works of the Soviet historian Kuzma Dubina concerning the German atrocities in Kyiv were published.1 It was then, for the first time, that the topic of the executions at Babi Yar was raised at a scientific level using eyewitness testimony. Between 1944 and 1946, in the published materials of the Extraordinary State Commission (ChGK) to establish and investigate the atrocities of the Nazi invaders and their accomplices, the total number of victims in occupied Kyiv was listed as more than 195 thousand “Soviet citizens”, of which at Babi Yar there were over 100 thousand people. The number of exterminated Jews was not identified separately.

The area became world famous in the postwar period. This was facilitated by the testimony of Kyiv’s residents at the Kyiv trial (1946). The collected materials and prose of the Soviet writer, publicist, and front-line correspondent of Jewish origin Ilya Ehrenburg (some of which were included in the Black Book),2 and the ChGK materials made public at the Nuremberg trials (1945–1946). In the 1960s, the topic of Babi Yar was raised in the poetry of Yevgeny Yevtushenko (Babi Yar, 1961), whose poems were set to music by composer Dmitry Shostakovich (13th Symphony, 1962) and in Holocaust witness Anatoly Kuznetsov’s eyewitness documentary story (Babi Yar, 1966) was republished several times, including in Kyiv in 1991.3 Testimony and interviews were often given by survivors of one of the “execution actions,” in particular Holocaust victim Dina Pronicheva (né Mstislavskaya) testified at the trial in Germany (1967) and appeared on Ukrainian radio.

Until the end of the 1980s, the Jewish tragedy was kept quiet. Soviet historians were busy tallying the total number of dead “civilians,” and fundamental science at the state level ignored the “Jewish question” for many years. Only on the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union historians, journalists, and public figures, especially those of Jewish origin, had the opportunity to “loudly” declare the tragedy of their co-religionists during the years of the Nazi occupation.

In 1990, a former military prosecutor, Julian Shulmeister, published a book indicating that Babi Yar, a former military shooting range with deep ravines, was not selected by the Germans by chance but because it could accommodate hundreds of thousands of corpses. He claimed that on September 29–30, 1941, the occupiers killed about 35 thousand people. In total, 150 thousand Jews died in the ravine.4 Subsequently, the figures of this non-professional historian have been corrected somewhat by professional research. To date, the number of Jewish victims at Babi Yar ranges from 39 to 45 to 70 thousand people. The gap in the numbers is due to different methodological approaches to the calculations, mainly whether the numbers are for individual “actions” in 1941 or are based on eyewitness testimony.

Sources

This article focuses on materials about Babi Yar published in Ukraine, mainly by Ukrainian scholars and witnesses of the Holocaust. Although, materials published abroad are mentioned. All known evidence about the crimes at Babi Yar can be divided into several typologies:

- Trial materials

- Collections of German documents and materials about events in Ukraine, including Babi Yar

- Reports from representatives of Soviet state security agencies on the situation in occupied Kyiv;

- Protocols of interrogations of surviving victims of the executions, eyewitnesses to the extermination of Jews, and participants in the burning of corpses

- Collections of memoirs of survivors of the Nazi occupation

Eyewitness accounts began to appear in 1946, although many of them were recorded immediately after the liberation of Kyiv in the fall of 1943. The first materials were published by the periodical press (Pravda Ukrainy and other Soviet newspapers). In the early 1990s, similar articles appeared in newspapers and magazines like Evreiskie Vesti and Kyiv. Since Ukrainian independence, the historiography of Babi Yar has expanded significantly using documents from National Socialist and Soviet periods, as well as memoir collections. These materials were published both in Ukraine and abroad, primarily thanks to the social activities of Ukrainian Jews in Israel, as well as the scientific staff of the Yad Vashem memorial complex. Among the earliest works, are the collections of Shmuel Spector and Mark Kipnis, historian Itzhak Arad, and Ephrem (Ephraim) Bauch, the head of the Union of Russian-language Writers of Israel, stand out.5 In 1993 and 1997, the memoirs of the former prisoners of the Syretsky concentration camp, who participated in the burning of corpses in the fall of 1943, were published abroad in separate publications.6

In Ukraine, the first collections of Soviet documents and Kyiv residents’ memoirs began appearing between 1995 and 2001, compiled by Leonid Abramenko and Ilya Levitas.7 They were followed by the publication of documents by local Kyiv historians Vitaly Nakhmanovich and Tatiana Evstafieva.8 Kharkiv researcher Alexander Kruglov carried out the important, painstaking, and necessary work of collecting, processing, and publishing German documents from the period of National Socialism. The historian and philosopher has published several collections of documents, which are currently one of the main sources for the study of the executions of Jews at Babi Yar.9 Among the memoirs, one can highlight the work of Andrey Kravchuk (excerpt from the book Memoirs of Kravchuk). The author recorded and published his first-hand accounts. In a small brochure, his grandfather, who lived near the ravine during the war, talked about the fate of some Jews in Kyiv and Proskurov (now Khmelnytskyi).10 In general, there are few separately published memoirs about the executions of Jews at Babi Yar.

In 2012, the Soviet journalist of Jewish origin Elena Rybina-Kosova, who was nine years old in 1941, published a book. She lived in the center of Kyiv, but with the advance of German troops, she was evacuated to Kuibyshev (now Samara). After the liberation of the Ukrainian capital, she returned home. In 1975, she was commissioned to write an essay about the Jewish tragedy in her hometown. Rybina found survivors of the executions of Kyivian Jews and surviving prisoners of the Syretsky camp and interviewed them. The memoirs of Dina Pronicheva and her son, as well as other testimonies, appear in Kuzma Dubina’s publication During the Years of Difficult Trials. In 2015, the second edition of the book was published, supplemented by the Kyivian woman’s memories in the essay We Could Not All Exist.11

For many years, Kyivian historian Boris Zabarko, a former prisoner of the Shargorod ghetto and the chairman of the All-Ukrainian Association of Former Jewish Prisoners of Ghettos and Nazi Concentration Camps, has been collecting evidence. Several collections of Jewish memoirs were published under his editorship. Among the published stories are some that relate to occupied Kyiv. Some of the memoirs had previously been published in Jewish and other newspapers, after which they were included in the first collections.12 Among the latest published sources, one can point to the books of Kyivian historians, which collected memoirs of Kyiv’s residents about the executions at Babi Yar,13 also the memoirs of the Righteous Sofia Yarova.14

Literature

The collapse of the USSR triggered a gradual shift away from the party nomenklatura influence on the methodology and topics of scientific research. This contributed to the fact that Babi Yar became a place of close and constant attention from scientists, religious and public organizations. Scientific publications that appeared after 1991 opened new horizons for further research on the topic. The first books on Holocaust commemoration were published, execution sites began to be studied, and calculations were made of the number of victims.

The project of two members of the Union of Artists of the Ukrainian SSR, Ada Rybachuk and Vladimir Melnichenko (who worked in the genre of sculpture, painting, graphics, and architecture), has been known since 1965. Twenty-five years after the tragedy, it was planned to create a monument to the “Victims of Fascism in the Shevchenkovsky district of Kyiv.”15 However, in 1976, the world-famous “Monument to Soviet Citizens and Prisoners of War, Soldiers and Officers of the Soviet Army, Shot by the German Fascists at Babi Yar” was opened, not based on the results of a competition, but on an ordered project.

There are more than thirty monuments installed around the site. At least six of them relate directly to the topic of the extermination of Jews (the latest installations include the “Crystal Wailing Wall” and the “Symbolic Synagogue,” near the Menorah). In the last years, the irregular and chaotic development of former cemeteries in Babi Yar has been discussed among scientists and religious, government, and public figures. The situation surrounding Ukrainian policies concerning the Holocaust, including the example of Babi Yar, is most fully reflected in the articles of Kyivian historian Yana Primachenko.16

Returning to the early 1990s, I would like to note that among professional historians, Felix Levitas was the first to write about the tragedy in Kyiv. He authored several books and articles devoted to the places of executions and the number of Jewish victims.17 The author’s latest book is based on materials from the family archive, memories of close relatives (father, aunt, himself), and documents from the archives of the Council of National Societies of Ukraine and the Museum of the History of the Nuremberg Trials. The publication also contains fragments from the author’s and co-author’s works Babi Yar. Pages of Tragedy, The Jews of Ukraine during the Second World War, and A History of the Holocaust.18 In 2022, Felix Levitas published a new article (co-authored) about the Soviet state policy of memory, which was characterized by a ban against covering the events of the Holocaust. It focuses attention on the Stalinist system’s struggle with the objective memories of people and the memory of society, which the totalitarian government tried to distort via silencing and creating ideological patterns and stereotypes. Only with the declaration of Ukraine’s independence did objective scientific research on the history of the Holocaust, the crimes of totalitarianism, and Nazism in Babi Yar become possible.19 The second person who drew attention to the silencing of the tragedy at Babi Yar was the historian Michael Koval, who devoted several specialized articles to the topic.20 In 1994, alongside the first publications of Felix Levitas and Michael Koval, the work of the German revisionist Herbert Tidemann was published; he questioned the executions at Babi Yar, the testimony of witnesses, and the vast number of victims.21

Monument “Menorah” to the executed Jews Source: Wikimedia

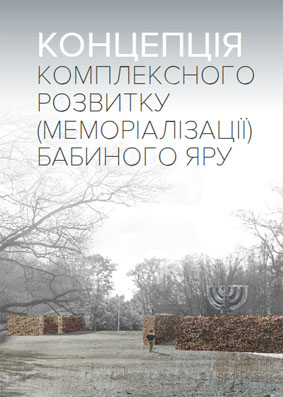

Among the latest scholar publications, one can highlight the memorialization concept for the landscape space in Babi Yar, prepared by the Institute of Ukrainian History of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in collaboration with various Kyivian researchers. The concept presents a holistic vision of perpetuating the memory of Babi Yar as a special place in the history of the Holocaust in Ukraine. The authors of the concept proposed the creation of a memorial park and museum complex, which will consist of the Babi Yar Memorial Museum and the Ukrainian Holocaust Museum. Propositions regarding the solution of legal, administrative, financial, and urban planning problems are outlined. Proposals were submitted regarding the thematic structure of future museum exhibitions, thematic maps of the memorial space, and explanations of key terms.22

By the end of the 1980s, the Jewish publicist, film director, and member of the International Anti-Fascist Committee, Alexander Shlaen, collected significant material about the events at Babi Yar. The researcher studied the testimonies of Jewish survivors. However, his work was published only in 1995. At the same time, one of the martyrologies of the victims of the Nazi genocide was published under his editorship.23 A significant contribution to the development of the historiography of Babi Yar was made by Ilya Levitas, Vitaly Nakhmanovich, Tatiana Evstafieva, Dmitry Malakov, Natalia Bernik, Sergey Karamash, and other Kyiv historians, archivists. Most of the works (journalistic, scientific, local history, historical, and archival) are united by a focused study of the area as a place of Jewish tragedy during the occupation and commemorative practices.

As the President of the Jewish Council of Ukraine and Chairman of the Babi Yar Memorial Foundation, local historian Ilya Levitas has devoted a significant part of his life to this topic. He carried out public, scientific, journalistic, and educational work. The Foundation he headed, in collaboration with various organisations, published a massive amount of generalised materials related to these events. As a schoolboy, Ilya Levitas began collecting the belongings of exterminated Jews. Over time, his collections formed the basis of the Babi Yar Museum, which was created under the Jewish Council of Ukraine. Some of the exhibits were transferred to the Museum of the History of Ukraine during the Second World War and other institutions. Separately, we can highlight the books published under the editorship of Ilya Levitas in memory of those killed at Babi Yar. The Foundation has identified the names of more than 23 thousand victims of genocide. In addition, the Foundation has published many collected materials about the rescued and their rescuers. The number of “Righteous of Babi Yar” (the title has been awarded by the Jewish Council of Ukraine since 1989) is more than six hundred people. In 2007, another title, “Children of the Righteous,” was established for individuals born before 1943 who were also at risk of destruction.24 Back in 1991, a book of memory, edited by Ismail Zaslavsky, was published based on materials by Ilya Levitas.25

Using German documents, Alexander Kruglov reconstructed events and counted the number of Jewish victims in Kyiv several times.26 According to his latest data, 37–38 thousand Jews were killed in the capital of Ukraine at the end of September – beginning of October 1941, and 39–40 thousand during the entire period of occupation. Kruglov considers the remaining known figures (from 50-55 to 150 thousand people) to be overestimated and unrealistic.

Many publications on the history of Babi Yar belong to the staff of the Kyiv History Museum. Local historian, Dmitry Malakov, has repeatedly described the work of German, Soviet, American, and British correspondents in Kyiv during the war, and published some of their photographic materials.27 Tatiana Evstafieva, based on archival documents, studied the history of the area and the Jewish tragedy for many years. The result of this was several articles.28 Vitaly Nakhmanovich consistently analyzes military events, carefully studying the history of the area, its execution sites, the biographies of participants and eyewitnesses, calculates the number of victims, compares witness testimony given in different years, and initiates projects to perpetuate the memory of victims of the Holocaust.29

Back in 2006, a brochure by the author Tatyana Tur was published in Kyiv, in which the territory of Babi Yar was explored and the crimes of the Soviet and Nazi authorities of the 1930s and early 1940s were analyzed. The author claims that the Nazis did not shoot at first but took Jews out of Kyiv.30 In general, the argumentation of Tatiana Tur is in agreement with the statements of Herbert Tiedemann, so her book can be classified as a revisionist publication that caused a lot of noise in Ukraine. In 2007, a monograph by the Israeli historian Itzhak Arad, dedicated to the fate of Soviet Jews during the war, was published in Dnepropetrovsk (now Dnepr). The section “The Ghetto and the Murder of Jews in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine” analyzes the events in occupied Kyiv and the executions at Babi Yar.31

Historian and archivist Michael Mitsel devoted one of his articles to the analysis of the Soviet government’s postwar prohibition of publicity about the tragedy; the collective, state memory of the Jewish tragedy; and the general lack of perpetuation of the memory of the victims of the Holocaust as a consequence of the fight against the “threat of Jewish bourgeois nationalism.” The ban on any form of Holocaust remembrance during the Stalinist period was effectively lifted during the Perestroika era. The collapse of the system contributed to the fact that the ideological apparatus began to listen to the opposite side’s arguments, which led to changes in the landscape of Babi Yar.32

The location of the executions and commemorative practices became a stumbling block in Lev Drobyazko’s publications. The researcher advocated for the creation of a national memorial in Babi Yar while arguing that the location of the Syretsky concentration camp and, accordingly, the place of executions and burials of Jews was incorrectly determined. He criticized Alexander Shlaen for creating a myth about the executions at the Jewish cemetery, and Ilya Levitas for the implausibility of the location of the Babi Yar tract.33

In 2012, a collection of materials from an international conference organised by the Kyiv Center for Holocaust Studies was published to mark the 70th anniversary of the shootings. It includes articles by famous Ukrainian and foreign scholars: Arkady Zeltser, Karel Berkhoff, Tatiana Evstafieva, Sergey Kot, Alexander Kruglov, Dmitry Malakov, Jurgen Matteus, Tanya Penter and others. All of the published materials to the history of Babi Yar. Only a few articles are devoted to analyzing the depiction of the Jewish tragedy in literature.34 In 2017, the Center republished the conference materials, supplementing them with materials by Vitaly Nakhmanovich.35 One of the authors of the collection, the Dutch historian Karel Berkhoff, has been researching the Holocaust in Ukraine for many years, in particular, the tragedy of Kyiv’s Jews, analyzing the number of victims and the memories of those who escaped after the executions, for example, the artist Dina Pronicheva.36

In 2013, Natalia Bernik published a book about Kyiv during the war years, in which one of the sections is devoted to the mass extermination of Jews at Babi Yar. In it, the author listed the names of representatives of the occupation authorities who were involved.37 At the same time, a worktitled Touching History (republished in 2017), by the famous Ukrainian scholar Yuri Shapoval was published. Written in a scientific and journalistic style, it covers various aspects of twentieth-century Ukrainian history. One of its sections is devoted to Babi Yar, the problem of silencing the Holocaust during the Soviet period, the displacement of Jewish victims’ memories to the margins of public consciousness, as well as the collective memory of the tragedy. The work analyzes the practice of separate memory and its fragmentation. This led to a competition of “victims” and a competition of “memories” and monuments.38 Similar material on the topic of Holocaust commemoration is in the article by Olga Kolesnik.39

Local historian Sergey Karamash has written a lot about the history of Kyiv. In his work, he cites the total figure of 39-40 thousand murdered Jews, citing Soviet archival documents and published German data. He describes the liquidation of Jews in different areas of the city, considering all those killed as victims of Babi Yar. The author tells the story of the establishment of all existing monuments to the victims of Nazi tyranny.40

On September 29-30, 2016, Ukraine held state-level commemorative events for the 75th anniversary of the mass shootings at Babi Yar. By this date, publications dedicated to the Jewish tragedy were published in Kyiv. One of the books was published as a collective monograph in Ukrainian and English, although it is more reminiscent of a collection of articles united by one topic. Researchers from Ukraine, Israel, Canada, the USA, and the Netherlands participated in its writing. This scientific work traces the history of Babyn Yar from ancient times to the present and the features of state memory policy in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods.41

Oral history remains a separate area of research. The processing of interviews with eyewitnesses and victims of the Holocaust continues to generate greater interest. Kharkov historian Gelinada Grinchenko (currently lives in Germany) analyzed some of the memories of contemporaries of pre-war and wartime Kyiv, which are stored in various video collections in the United States.42

Several articles on the Holocaust and the problem of preserving the memory of Babi Yar were published by the director of the Tkuma Institute, historian Igor Shchupak. The historian noted that the state policy of memory concerning the Jewish tragedy has undergone a serious test of awareness: from silencing the topic and terminology of the “Holocaust” to open discussion about repentance.43 A similar evolution is analyzed in dissertation researcher Tkuma Anna Medvedovskaya. The young scientist proves that the depiction of the Jewish tragedy by the Soviet creative intelligentsia in literature, music, and cinema had a more significant effect on Western audiences because it was openly discussed and not banned or censored there. In 2023, a monograph was published based on the dissertation.44

Among Ukrainian scholars who continue to be interested in the tragic history of Babi Yar and the perpetuation of its memory are Yuri Radchenko, Stanislav Sergienko, Nikolay Borovyk, Vladislav Hrynevych, and Olga Radchenko.45 Studied various aspects of historical, cultural, and ideological layers surrounding the memory of Babi Yar in the publications of foreign researchers.46

Since 2022, the International Memorial Center of the Holocaust “Babyn Yar” (Kyiv) has begun to publish the electronic English-language journal Eastern European Holocaust Studies, in which the topic of Babi Yar occupies a special place. The journal publishes both Ukrainian and foreign scientists. From the first articles, one can highlight the material by Arleen Ionescu on the analysis of the memoirs of Holocaust witnesses Anatoly Kuznetsov and Zakhar (Ziama) Trubakov.47

Conclusions

This brief historiographic review, which does not pretend to be an absolute or exhaustive selection of works, demonstrates the main directions of scientific research: local history (studying the history of the area and places of executions), archival (publication of German and Soviet archival documents), oral historical (analysis and publication of interviews), ego-documentary (publication of ego-documents, mainly memories), statistical (counting victims), and commemorative (Holocaust memorialisation). All directions continue to develop, so it is too early to draw an end to the research into the history of Babi Yar.

The analysis of the published materials testifies to the multifaceted nature of the Jewish history of Babi Yar. It is full of events, different interpretations of these events, in particular, many years of research into the places where Jews were shot. And the memory of the events of September 1941 is multi-layered, tragic and sad. Thanks to the publication of the memoirs of Holocaust eyewitnesses, modern historians are able to accurately reconstruct the events of past years and understand the reasons for the help or lack of help to Jews by different strata of Ukrainian society, as well as representatives of the occupations structures, the methods of the struggle of Jews for their own survival during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine. Among the prospects for further research, which have not yet received serious scientific implementation in the form of separately published books, one can highlight the analysis of the memories of representatives of the occupation structures about the tragedy at Babi Yar; materials from the postwar trials of Nazi criminals, especially those who were direct participants in the “special actions” in occupied Kyiv.

Translated from Russian by Amber N. Nickell

Elements from this article have been previously published:

- Mykhailiuk, M. (2016). Ukrainian historiography of Babi Yar: main directions, trends, research prospects, Proceedings of the international scientific conference “Jews of Europe and the Middle East: tradition and modernity. History, languages, literature” (St. Petersburg, April 17, 2016). St. Petersburg, 233-239 [in Russian]. Михайлюк, М. (2016). Украинская историография Бабьего Яра: основные направления, тенденции, перспективы исследования, Материалы международной научной конференции «Евреи Европы и Ближнего Востока: традиция и современность. История, языки, литература» (г. Санкт-Петербург, 17 апреля 2016 г.). Санкт-Петербург, 233-239.

- Mykhailiuk, M. (2017). The Newest Historiography of Babi Yar: An Analysis of Recent Publications, Jews of Europe and the Middle East: Heritage and Its Retransmission. History, Languages, Literature, Culture: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference in Memory of E. Bramson-Alpernene April 23, 2017 St. Petersburg, 39-47 (in Russian). Михайлюк, М. (2017). Новейшая историография Бабьего Яра: анализ последних публикаций, Евреи Европы и Ближнего Востока: наследие и его ретрансляция. История, языки, литература, культура: Материалы международной научной конференции памяти Э. Брамсон-Альпернене 23 апреля 2017 г. Санкт-Петербург, 39-47.

- Mykhailiuk, M. (2016). Babyn Yar yak memuarno-doslidnytske pole zakhidnoi istoriohrafii (do 75-i richnytsi yevreyskoi trahedii) [Babi Yar as a memoir-research field of Western historiography (to the 75th anniversary of the Jewish tragedy)]. Military-historical meridian: electronic scientific journal, 3(13), Retrieved from http://vim.gov.ua/images/sbor/VIM_13_2016_5-18.pdf (in Ukrainian). Михайлюк, М. (2016). Бабин Яр як мемуарно-дослідницьке поле західної історіографії (до 75-ї річниці єврейської трагедії), Військово-історичний меридіан: електронний науковий журнал. 3(13). URL: http://vim.gov.ua/images/sbor/VIM_13_2016_5-18.pdf.

- Mykhailiuk, M. (2023). Reflection of the Babyn Yar tragedy in domestic historiography and published sources (1991-2022), Scientific works of the Kamianets-Podilskyi National University named after I. Ohienko. Series: Historical Sciences, (40), 9-28 (in Ukrainian). Михайлюк, М. (2023). Відображення трагедії Бабиного Яру у вітчизняній історіографії та опублікованих джерелах (1991-2022 рр.), Наукові праці Кам’янець-Подільського національного університету імені І. Огієнка. Серія: Історичні науки, (40), 9-28.

- Dubyna, K. (1945). 778 Tragic Days of Kyiv. Kyiv: Ukrderzhvydav, 95 p. (in Ukrainian). Дубина, К. (1945). 778 трагічних днів Києва. Київ: Укрдержвидав, 95 с. ↩

- Grossman, V. & Erenburg, I. (Ed.). (2020). The Black Book: About the Criminal Mass Extermination of Jews by German-Fascist Invaders in the Temporarily Occupied Areas of the Soviet Union and Extermination Camps in Poland During the War of 1941-1945. Kyiv: Spirit and Letter, 520 s. (in Ukrainian). Гросман, В. & Еренбург І. (Ред.). (2020). Чорна книга: про злочинне повсюдне знищення євреїв німецько-фашистськими загарбниками в тимчасово окупованих районах Радянського Союзу та таборах знищення в Польщі під час війни 1941-1945 років. Київ: Дух і Літера, 520 с. ↩

- Kuznetsov, A. (1991). Babyn Yar: Novel-document. Kyiv: Soviet Writer, 352 s. (in Ukrainian). Кузнецов, А. (1991). Бабин Яр: Роман-документ. Київ: Радянський письменник, 352 с. ↩

- Schulmeister, Y. (1990). Hitlerism in Jewish History. Kyiv: Politizdat, 133–135. (in Russian). Шульмейстер, Ю. (1990). Гитлеризм в истории евреев. Киев: Политиздат, 133–135. ↩

- Spektor, S. & Kipnis, M. (1991). Babi Yar: On the 50th Anniversary of the Tragedy (September 29-30, 1941). Jerusalem: Aliya Library, 184 p. (in Russian); Cпектор, Ш. & Кипнис, М. (1991). Бабий Яр: К 50-летию трагедии (29-30 сентября 1941 г.). Иерусалим: Библиотека «Алия», 184 с.; Arad, I. (Ed.) (1991). The Destruction of the Jews of the USSR during the German Occupation (1941-1944): A Collection of Documents and Materials. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 424 p. (in Russian); Арад, И. (Ed.) (1991). Уничтожение евреев СССР в годы немецкой оккупации (1941-1944): Сборник документов и материалов. Иерусалим: Яд Вашем, Тарбут, 424 с.; Bauch, E. (Ed.) (1981). Babi Yar. Israel: Bat-Yam, 100 p. (in Russian); Баух, Е. (Ed.) (1981). Бабий Яр. Израиль: Бат-Ям, 100 с.; Bauch, E. (Ed.). (1993). Babi Yar: Documentary Materials. 2nd ed. Tel Aviv: Moria, 172 p. (in Russian). Баух, Е. (Ed.). (1993). Бабий Яр: Документальные материалы. 2-е изд. Тель-Авив: Мория, 172 с. ↩

- Budnik, D. & Kaper, Ya. 1993. Nichto ne zabyto. Evreyskie sudby v Kieve 1941–1943 (Nothing is forgotten. Jewish destinies in Kyiv 1941–1943). Konstants. (in Russian). Будник, Д. & Капер, Я. (1993). Ничто не забыто. Еврейские судьбы в Киеве (1941-1943). Констанц: Chartung-Gorre Verlag, 318 с.; Trubakov, Z. (1997). The Secret of Babi Yar. Documentary Chronicle. Tel Aviv, 184 p. (in Russian) Трубаков, З. (1997). Тайна Бабьего Яра. Документальная повесть-хроника. Тель-Авив, 184 с. ↩

- Abramenko, L. (Comps.). (1995). The Kyiv process. Documents and materials. Kyiv: Lybid, 208 s. (in Ukrainian). Абраменко, Л. (1995). Київський процес. Документи і матеріали. Київ: Либідь, 208 с.; Levitas, I. (Comps.). (2001). Memory of Babi Yar: Memoirs, Documents. Kyiv: Jewish Council of Ukraine, 256 s. (in Russian). Левитас, И. (Сост). (2001). Память Бабьего Яра: Воспоминания, документы. Киев: Еврейский совет Украины, 256 с. ↩

- Evstafieva, T. & Nahmanovich, V. (Comp.). (2004). Babi Yar: man, power, history: Documents and materials. Book 1: Historical topography. Chronicle of events. Kyiv: Vneshtorgizdat, 597 s. (in Russian). Евстафьева, Т. & Нахманович, В. (2004). Бабий Яр: человек, власть, история: Документы и материалы. Кн. 1: Историческая топография. Хроника событий. Киев: Внешторгиздат, 597 с. ↩

- Kruglov, A. (Comps.) (2002). Collection of documents and materials about the destruction of the Jews of Ukraine by the Nazis in 1941-1944. Kyiv: Institute of Jewish Studies, 486 s. (in Russian). Круглов, А. (2002). Сборник документов и материалов об уничтожении нацистами евреев Украины в 1941–1944 гг. Киев: Институт иудаики, 486 с.; Kruglov, A. (2011). The tragedy of Babi Yar in German documents. Dnepropetrovsk: Tkuma, 140 s. (in Russian). Круглов, А. (2011). Трагедия Бабьего Яра в немецких документах. Днепропетровск: Ткума, 140 с.; Kruglov, A. & Umansky, A. (2019). Babi Yar: Victims, Saviors, Executioners. Dnipro: Tkuma; Lira LTD, 280 s. (in Russian). Круглов, А. & Уманский, А. (2019). Бабий Яр: жертвы, спасители, палачи. Днипро: «Ткума»; ЧП «Лира ЛТД», 280 с. ↩

- Kravchuk, A. (2004). Babi Yar. Kyiv: Veta-copyservice, 38 s. (in Russian). Кравчук, А. (2004). Бабий Яр. Киев: Вета-кописервис, 38 с. ↩

- Rybina-Kosova, E. (2012). We might not all be! Babi Yar. Feature article. Eyewitness accounts. Documents. Kyiv: Poetry, 112 s. (in Russian). Рыбина-Косова, Е. (2012). Нас всех могло не быть! Бабий Яр. Очерк. Свидетельства очевидцев. Документы. Киев: Поэзия, 112 с.; Rybina-Kosova, E. (2015). We might not all be! Babi Yar: essay, eyewitness accounts, documents. (2th ed.). Kyiv: Poetry, 2015. 127 s. (in Russian). Рыбина-Косова, Е. (2015). Нас всех могло не быть! Бабий Яр. Очерк. Свидетельства очевидцев. Документы. Изд. 2-е. Киев: Поэзия, 127 с. ↩

- Zabarko, B. (Comps.). (1999-2000). Only we remained alive…: Evidence and documents. Kyiv: Zadruga, 578 s.; 2nd ed., 578 s. (in Russian). Забарко, Б. (1999). Живыми остались только мы…: Свидетельства и документы. Киев: Задруга, 578 с.; Забарко, Б. (2000). Живыми остались только мы…: Свидетельства и документы. Изд. 2-е. Киев: Задруга, 578 с. ; Zabarko, B. (Comps.). (2006-2007). Life and Death in the Age of the Holocaust. Certificates and documents. In 3 books. Kyiv: Spirit and Litera. Book 1, 523 s.; Book 2, 539 s.; Book. 3, 699 s. (in Russian). Забарко, Б. (2006-2007). Жизнь и смерть в эпоху Холокоста. Свидетельства и документы: в 3 х кн.: Кн. 1. Киев: (б. и.), 523 с.; Кн. 2. Киев: Дух и Литера, 539 с.; Кн. 3. Киев: Дух и Литера, 699 с.; Zabarko, B. (Comps.). (2013-2014). We wanted to live. Certificates and documents. In 2 books. Kyiv: Spirit and Litera, 592 s.; Book 2, 792 s. (in Russian). Забарко, Б. (2013-2014). Мы хотели жить. Свидетельства и документы: в 2 х кн. Киев: Дух и Литера. Кн. 1. 592 с.; Кн. 2. 792 с. ↩

- Kot, S. (Comps.). (2019). Kyiv, 1941. Babi Yar: Memories of contemporaries. Kyiv: Institute of History of Ukraine, 53 s. (in Ukrainian). Кот, С. (2019). Київ 1941 р. Бабин Яр: Спогади сучасників. Київ: Інститут історії України, 53 с.; Borovyk, M., Drobkova, N. & Pastushenko, T. (Comp.). (2020). The Second World War and the Nazi occupation in the memories of Kyivans. Kyiv: Salit-knyga, 352 s. (in Ukrainian). Боровик, М., Дробкова, Н. & Пастушенко, Т. (2020). Друга світова війна та нацистська окупація у спогадах киян. Київ: Саліт-книга, 352 с. ↩

- Yarova, S. (2022). My life during the occupation. Kyiv: Dmytro Burago Publishing House, 70 s. (in Ukrainian). Ярова, С. (2022). Моє життя в період окупації. Київ: Видавничий дім Дмитра Бураго, 70 с. English version available online: https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/media/sofia-yarova-book-eng.pdf. ↩

- Rybachuk, A. & Melnychenko, V. (Ed.). (1991). Babi Yar: book-requiem – book-monument (for the 50th anniversary of the tragedy). Kyiv, 79 s. (in Ukrainian). Рибачук, А. & Мельниченко, В. (Ed.) (1991). Бабин Яр: книга-реквієм – книга-пам’ятник (до 50-річчя трагедії). Київ, 79 с. ↩

- Primachenko, Y. (2018). Ukrainian historical politics and the Holocaust: problems of historical understanding. Forum of Recent Eastern European History and Culture (Russian Edition), (1-2), 280–297 (in Russian). Примаченко, Я. (2018). Украинская историческая политика и Холокост: проблемы исторического осмысления, Форум новейшей восточноевропейской истории и культуры (Русское издание), (1-2), 280-297; Prymachenko, Y. (2021). Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial between third memory boom and hybrid war, Baltic Rim Economies Review, (2), 27. ↩

- Levitas, F. & Shimanovsky, M. (1991). Babi Yar: pages of tragedy. Kyiv: Sled, 54 s. (in Russian). Левитас, Ф. & Шимановский, М. (1991). Бабий Яр: страницы трагедии. Киев: След, 54 с.; Levitas, F. (1997). Jews of Ukraine during the Second World War. Kyiv: Vyriy, 272 s. (in Ukrainian). Левітас, Ф. (1997). Євреї України в роки Другої світової війни. Київ: Вирій, 272 с.; Levitas, F. (1999). Babi Yar (1941-1943), The Catastrophe and Resistance of Ukrainian Jewry (1941-1944): Essays on the History of the Holocaust and Resistance in Ukraine. Kyiv: Institute of Political and Ethnonational Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 88–117. (in Ukrainian). Левітас, Ф. (1999). Бабин Яр (1941–1943), Катастрофа та опір українського єврейства (1941–1944): Нариси з історії Голокосту і Опору в Україні. Київ: Інститут політичних і етнонаціональних досліджень НАН України, 88–117. ↩

- Levitas, F. (2016). Babi Yar. Fate and memory. Kyiv: Our hour, 144 s. (in Russian). Левитас, Ф. (2016). Бабий Яр. Судьбы и память. Киев: Наш час, 144 с. ↩

- Ramazanov, Sh. & Levitas, F. (2022). Babyn Yar. The Holocaust is a taboo topic in Soviet historiography, Pages of history, 53, 113–130. (in Ukrainian). Рамазанов, Ш. & Левітас, Ф. (2022). Бабин Яр. Голокост – табуйовані теми радянської історіографії, Сторінки історії, (53), 113–130. ↩

- Koval, M. (1991). Babi Yar (September 1941 – September 1943), Ukrainian Historical Journal, 9, 80–86; 12, 53–62. (in Ukrainian). Коваль, М. (1991). Бабин Яр (вересень 1941 – вересень 1943), Український історичний журнал, (9), 80–86; (12), 53–62; Koval, M. (1998). The tragedy of Babi Yar: history and modernity, New and Recent History, 4. (in Russian). Коваль, М. (1998). Трагедия Бабьего Яра: история и современность, Новая и Новейшая история, (4); Koval, M. (2001). The pain doesnt subside, Memory of Babi Yar: Memoirs, Documents. Kyiv: Jewish Council of Ukraine, Babi Yar Memory Foundation, 25–35. (in Russian). Коваль, М. (2001). Боль не утихает, Память Бабьего Яра: Воспоминания, документы. Киев: Еврейский совет Украины, Фонд «Память Бабьего Яра», 25–35. ↩

- Tidemann, G. (1994). Babyn Yar: Critical Questions and Comments. URL: http://babiyarkiev.blogspot.ru/2011/09/blog-post_03.html (in Ukrainian). Тідеманн, Г. (1994). Бабин Яр: Критичні питання та коментарі. URL: http://babiyarkiev.blogspot.ru/2011/09/blog-post_03.html. ↩

- Boryak, G., Lysenko, O., Nahmanovych, V. & Podolsky, A. (Comps.). (2021). The concept of comprehensive development (memorialization) of Babi Yar with the expansion of the boundaries of the National Historical and Memorial Reserve «Babyn Yar». Kyiv: Institute of History of Ukraine, 200 s. (in Ukrainian). Концепція комплексного розвитку (меморіалізації) Бабиного Яру з розширенням меж Національного історико-меморіального заповідника «Бабин Яр». Вид. 2-ге. Київ: Інститут історії України, 2021. 200 с. ↩

- Schlaen, A. (1995). Babi Yar: Artistic journalism. Kyiv: Apricos, 414 s. (in Russian). Шлаен, А. (1995). Бабий Яр: Художественная публицистика. Киев: Абрикос, 414 с.; Schlaen A. & Malicka A. (1995). Forever in memory: Martyrology of the victims of the Nazi genocide at Babi Yar. Kyiv: Apricos, 168 s. (in Russian). Шлаен, А. & Малицкая, А. (Ed.) (1995). Навеки в памяти: Мартиролог жертв нацистского геноцида в Бабьем Яру. Киев: Абрикос, 168 с. ↩

- Levitas, I. (Comps.) (1999). Memory book. Babi Yar. Kyiv: Jewish Council of Ukraine, Babi Yar Memory Foundation, 300 s. (in Russian). Левитас, И. (Ed.) (1999). Книга памяти. Бабий Яр. Киев: Еврейский совет Украины, Фонд «Память Бабьего Яра», 300 с.; Levitas, I. (Comps.). (2001). The Righteous of Babi Yar. Kyiv: Jewish Council of Ukraine, 256 s. (in Russian). Левитас, И. (Ed.) (2001). Праведники Бабьего Яра. Киев: Еврейский совет Украины, 256 с.; Levitas, I. (Comps.). (2005). Babi Yar. Memory book. Kyiv: Steel, 570 s. (in Russian). Левитас, И. (Ed.) (2005). Бабий Яр. Книга памяти. Киев: Сталь, 570 с.; Levitas, I. (Comps.). (2005). Babi Yar. Saviors and salvation. Kyiv: Steel, 576 s. (in Russian). Левитас, И. (Ed.) (2005). Бабий Яр. Спасители и спасенные. Киев: Сталь, 576 с.; Levitas, I. (Comps.). (2008). The Righteous of Babi Yar. Kyev: Ethnos, 368 s. (in Ukrainian). Левітас, І. (Ed.) (2008). Праведники Бабиного Яру. Київ: Етнос, 368 с.; Levitas, I. (Comps.). (2008). Children of Babi Yar. Kyiv: Jewish Council of Ukraine, Babi Yar Memory Foundation, 67 s. (in Russian). Левитас, И. (2008). Дети Бабьего Яра. Киев: Еврейский совет Украины, Фонд «Память Бабьего Яра», 67 с.; Levitas, I. (Comps.). (2011). Babi Yar: Tragedy, History, Memory (1941-2011). Kyiv: National Historical and Memorial Reserve «Babi Yar», 617 s. (in Russian). Левитас, И. (2011). Бабий Яр: Трагедия, история, память (1941–2011). Киев: Национальный историко-мемориальный заповедник «Бабий Яр», 617 с. ↩

- Zaslavsky, I. (Comps.). (1991). Memory book. Dedicated to the victims of Babi Yar. Kyiv: Oberig, 134 s. (in Russian). Заславский, И. (1991). Книга памяти: имена погибших в Бабьем Яру (Посвящается жертвам Бабьего Яра). Киев: Обериг, 134 с. ↩

- Kruglov, A. (2001). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Kyiv, Memory of Babi Yar: Memoirs, Documents. Kyiv: Jewish Council of Ukraine, 36–42 (in Russian). Круглов, А. (2000). Энциклопедия Холокоста. Киев, Память Бабьего Яра: Воспоминания, документы, 36–42. ↩

- Malakov, D. (2004). Kyiv and Babi Yar on German photographic film in autumn 1941, Babi Yar: man, power, history: Documents and materials (Book 1: Historical topography. Chronicle of events). Kyiv: Vneshtorgizdat, 164–170 (in Russian). Малаков, Д. (2004). Киев и Бабий Яр на немецкой фотопленке осени 1941 г., Бабий Яр: человек, власть, история: Документы и материалы. Кн. 1: Историческая топография. Хроника событий, 164–170; Malakov, D. (2007). Once again about Babi Yar in photographs, The Second World War and the Fate of the Peoples of Ukraine: Materials of the Second All-Ukrainian Scientific Conference (Kyiv, October 30–31, 2006). Kyiv: Zovnishtorgvydav, 279–283. (in Ukrainian). Малаков, Д. (2007). Ще раз про Бабин Яр на фотознімках, Друга світова війна і доля народів України: Матеріали Другої Всеукраїнської наукової конференції (Київ, 30–31 жовтня 2006). Київ: Зовнішторгвидав, 279–283. ↩

- Evstafieva, T. (2004). The tragedy of Babi Yar in 1941–1943 (according to the documents of the Branch State Archive of the SBU), From the archives of the VUCHK-GPU-NKVD-KGB, 1/2 (22/23), 354–386. (in Ukrainian). Євстафьєва, Т. (2004). Трагедія Бабиного Яру у 1941–1943 рр. (за документами Галузевого державного архіву СБУ), З архівів ВУЧК-ГПУ-НКВД-КГБ, (1/2), 354–386; Evstafieva, T. (2007). The tragedy of Babi Yar (1941-1945), The Second World War and the Fate of the Peoples of Ukraine: Materials of the Second All-Ukrainian Scientific Conference (Kyiv, October 30–31, 2006). Kyiv: Zovnishtorgvydav, 263–278. (in Russian). Евстафьева, Т. (2007). Трагедия Бабьего Яра (1941–1945), Друга світова війна і доля народів України: Матеріали Другої Всеукраїнської наукової конференції (Київ, 30–31 жовтня 2006). Київ: Зовнішторгвидав, 263–278; Evstafieva, T. (2011). The tragedy of Babi Yar through the prism of archival documents of the Security Service of Ukraine, Archives of Ukraine, (5), 137–158. (in Ukrainian). Євстафьєва, Т. (2011). Трагедія Бабиного Яру крізь призму архівних документів Служби безпеки України, Архіви України, (5), 137–158. ↩

- Nachmanovich, V. (2004). Sources and literature. Problems of systematization and features of the study. Babi Yar: man, power, history: Documents and materials (Book 1: Historical topography. Chronicle of events). Kyiv: Vneshtorgizdat, 21–65. (in Russian). Нахманович, В. (2004). Источники и литература. Проблемы систематизации и особенности изучения, Бабий Яр: человек, власть, история: Документы и материалы. Кн. 1: Историческая топография. Хроника событий. Киев: Внешторгиздат, 21–65; Nachmanovich, V. (2004). Executions and burials in the area of Babi Yar during the German occupation of Kyiv in 1941-1943. Problems of chronology and topography, Babi Yar: man, power, history: Documents and materials (Book 1: Historical topography. Chronicle of events). Kyiv: Vneshtorgizdat, 84–163. (in Russian). Нахманович, В. (2004). Расстрелы и захоронения в районе Бабьего Яра во время немецкой оккупации Киева 1941–1943 гг. Проблемы хронологи и топографии, Бабий Яр: человек, власть, история: Документы и материалы. Кн. 1: Историческая топография. Хроника событий. Киев: Внешторгиздат, 84–163; Nahmanovych, V. (2007). To the question of the composition of the participants of punitive actions in occupied Kyiv (1941-1943), The Second World War and the Fate of the Peoples of Ukraine: Materials of the Second All-Ukrainian Scientific Conference (Kyiv, October 30-31, 2006). Kyiv: Zovnishtorgvydav, 227–262. (in Ukrainian). Нахманович, В. (2007). До питання про склад учасників каральних акцій в окупованому Києві (1941–1943), Друга світова війна і доля народів України: Матеріали Другої Всеукраїнської наукової конференції (Київ, 30–31 жовтня 2006). Київ: Зовнішторгвидав, 227–262; Nahmanovych, V. (2007). Bukovynsky kurin and mass executions of Kyiv Jews in the fall of 1941, Ukrainian Historical Journal, 3, 76–97. (in Ukrainian). Нахманович, В. (2007). Буковинський курінь і масові розстріли євреїв Києва восени 1941 р., Український історичний журнал, (3), 76-97; Nahmanovych, V. (2011). Babi Yar: History, modernity, future? (reflections on the 70th anniversary of the Kyiv massacre of September 29–30, 1941), Ukrainian Historical Journal, 6, 105–121. (in Ukrainian). Нахманович, В. (2011). Бабин Яр: Історія, сучасність, майбутнє? (роздуми до 70 річчя київської масакри 29–30 вересня 1941 р.), Український історичний журнал, (6), 105–121; Nahmanovych, V. (Comps.). (2017). Babi Yar: memory against the background of history. Album-catalogue of the multimedia exhibition for the 75th anniversary of the Babi Yar tragedy. Kyiv: Laurus, 252 s. (in Ukrainian). Нахманович, В. (2017). Бабин Яр: пам’ять на тлі історії. Альбом-каталог мультимедійної виставки до 75-річчя трагедії Бабиного Яру. Київ: Laurus, 252 с.; Nahmanovych, V. (2021). Babi Yar: problems of urban space formation, Kyiv and Kyivans. Materials of the annual scientific and practical conference. (Vol. 13). Kyiv: Institute of History of Ukraine NAS, 223–228. (in Ukrainian). Нахманович, В. (2021). Бабин Яр: проблеми формування міського простору, Київ і кияни. Матеріали щорічної науково-практичної конференції. Вип. 13. Київ: Інститут історії України НАН України, 223-228. ↩

- Tur, T. (2006). The Truth about Babyn Yar: Documentary Research. Kyiv: MAUP, 23 p. (in Ukrainian). Тур, Т. (2006). Правда про Бабин Яр: Документальне дослідження. Київ: МАУП, 23 с. ↩

- Arad, I (2007). The Catastrophe of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Soviet Union (1941-1945). Dnepropetrovsk, Moskva: Tkuma; Lira LTD; Tsentr «Holokost», 816 s. (in Russian). Арад, И. (2007). Катастрофа евреев на оккупированных территориях Советского Союза (1941-1945). Днепропетровск-Москва: Центр «Ткума»; «Лира ЛТД»; Центр «Холокост», 816 с. ↩

- Mitsel, M. (2007). The ban on perpetuating memory as a way of hushing up the Holocaust: the practice of the Communist Party of Ukraine in relation to Babi Yar, The Holocaust and modernity. Studios in Ukraine and the World, 1(2), 9-30 (in Russian). Мицель, М. (2007). Запрет на увековечение памяти как способ замалчивания Холокоста: практика КПУ в отношении Бабьего Яра, Голокост і сучасність. Студії в Україні і світі, 1(2), 9-30. ↩

- Drobyazko, L. (2009). Babyn Yar. What? Where? When? Kyiv: Kiy, 55 s. (in Ukrainian). Дроб’язко, Л. (2009). Бабин Яр. Що? Де? Коли? Київ: Кий, 55 с. ↩

- Podolsky, A. & Tyagly, M. (Comps.). (2012). Babyn Yar: mass murder and its memory: Proceedings of the international scientific conference (Kyiv, October 24-25, 2011). Kyiv: UCVIG, Gromad. to honor the memory of the victims of Babyn Yar, 256 s. (in Ukrainian). Подольський, А. & Тяглий, М. (Упорядн.). (2012). Бабин Яр: масове убивство і пам’ять про нього: Матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції (Київ, 24-25 жовтня 2011 р.). Київ: УЦВІГ, Громад. к-т для вшанування пам’яті жертв Бабиного Яру, 256 с. ↩

- Podolsky, A., Tyagly, M. & Nakhmanovych, V. (Comps.). (2017). Babyn Yar: mass murder and its memory: Proceedings of the international scientific conference (Kyiv, October 24-25, 2011). (2th ed.). Kyiv: UCVIG, Gromad. to honor the memory of the victims of Babyny Yar, 288 с. (in Ukrainian). Подольський, А., Тяглий, М. & Нахманович, В. (Упорядн.). (2017). Бабин Яр: масове убивство і пам’ять про нього: Матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції (Київ, 24-25 жовтня 2011 р.) (2-ге вид.). Київ: УЦВІГ, Громад. к-т для вшанування пам’яті жертв Бабиного Яру, 288 c.; Nahmanovych, V. (2017). History. Modernity. Future? (reflections on the 70th anniversary of the Kyiv massacre of September 29-30, 1941), Babyn Yar: mass murder and its memory: Proceedings of the international scientific conference (Kyiv, October 24-25, 2011). Kyiv: UCVIG, Gromad. to honor the memory of the victims of Babi Yar, 221–244. (in Ukrainian). Нахманович, В. (2017). Історія. Сучасність. Майбутнє? (роздуми до 70-річчя київської масакри 29-30 вересня 1941 р.), Бабин Яр: масове убивство і пам’ять про нього: Матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції (Київ, 24-25 жовтня 2011 р.). Вид. 2-ге. Київ: УЦВІГ, Громад. к-т для вшанування пам’яті жертв Бабиного Яру, 221-244; Nahmanovych, V. (2017). Catalog of security and information boards, monuments and memorial signs related to the history of Babyn Yar (as of June 1, 2017). Babyn Yar: mass murder and its memory: Proceedings of the international scientific conference (Kyiv, October 24-25, 2011). Kyiv: UCVIG, Gromad. to honor the memory of the victims of Babyn Yar, 245–280. (in Ukrainian). Нахманович, В. (2017). Каталог охоронних та інформаційних дощок, пам’ятників і пам’ятних знаків, пов’язаних з історією Бабиного Яру (станом на 1 червня 2017 р.), Бабин Яр: масове убивство і пам’ять про нього: Матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції (Київ, 24-25 жовтня 2011 р.). Вид. 2-ге. Київ: УЦВІГ, Громад. к-т для вшанування пам’яті жертв Бабиного Яру, 245–280. ↩

- Berkhoff, K. (2011). Harvest of despair. Life and death in Ukraine under Nazi rule. Kyiv: Kritika, 455 p. (in Ukrainian). Беркгоф, К. (2011). Жнива розпачу. Життя і смерть в Україні під нацистською владою. Київ: Критика, 455 с.; Berkhoff, K. (2012). The Holocaust in Ukraine, Modern discussions about the Second World War: a collection of scientific works and speeches of Ukrainian and foreign historians. Lviv: ZUKTS, 66-81(in Ukrainian). Беркгоф, К. (2012). Голокост в Україні, Сучасні дискусії про Другу світову війну: збірник наукових праць та виступів українських і зарубіжних істориків. Львів: ЗУКЦ, 66-81; Berkhoff, K. (2012). Babyn Yar in Western cinematography. Materials of the international conference «Crimes of totalitarian regimes in Ukraine: Scientific and educational perspective» (Vinnytsia, November 21-22, 2009). Kyiv: UCVIG, 101-106 (in Ukrainian). Беркгоф, К. (2012). Бабин Яр у західній кінематографії, Матеріали міжнародної конференції «Злочини тоталітарних режимів в Україні: Науковий та освітній погляд» (Вінниця, 21-22 листопада 2009 р.). Київ: УЦВІГ, 101-106; Berkhoff, K. (2012). Babyn Yar: the site of the largest mass shooting of Jews by the Nazis in the Soviet Union, Babyn Yar: mass murder and its memory: materials of the international scientific conference (Kyiv, October 24–25, 2011). Kyiv: UCVIG, 8-20 (in Ukrainian). Беркгоф, К. (2012). Бабин Яр: місце наймасштабнішого розстрілу євреїв нацистами в Радянському Союзі. Бабин Яр: масове убивство і пам’ять про нього: матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції (Київ, 24–25 жовтня 2011 р.). Київ: УЦВІГ, 8-20; Berkhoff, K. (2015). The story of Dina Pronicheva, who survived Babyn Yar: German, Jewish, Soviet, Russian and Ukrainian documents, The Shoah in Ukraine: history, testimony, perpetuation. Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 397-432 (in Ukrainian). Беркгоф, К. (2015). Історія Діни Пронічевої, яка пережила Бабин Яр: німецькі, єврейські, радянські, російські та українські документи, Шоа в Україні: історія, свідчення, увічнення. Київ: Дух і Літера, 397-432. ↩

- Bernyk, N. (2013). Kyiv in the Great Patriotic War. Kyiv: Universe, 800 s. (in Ukrainian). Берник, Н. (2013). Київ у Великій Вітчизняній війні. Київ: Всесвіт, 800 с. ↩

- Shapoval, Yu. (2013). Babyn Yar: life and death nearby. Touch history. Kyiv-Dnipropetrovsk: Parliament Publishing House, Lira, Tkuma, 13-17 (in Ukrainian). Шаповал, Ю. (2013). Бабин Яр: життя і смерть поруч, Торкнутись історії. Київ-Дніпропетровськ: Парламентське видавництво, Ліра, Ткума, 13-17; Shapoval, Yu. (2017). Babyn Yar: life and death nearby, Touch history (2th ed.).Kyiv, 13-24 (in Ukrainian). Шаповал, Ю. (2017). Бабин Яр: життя і смерть поруч, Торкнутись історії. Изд. 2-е. Київ, 13-24. ↩

- Kolesnyk, O. (2014). Babyn Yar as a place of remembrance: an overview of commemorative practices and memorials, Acta studiosa historica: collection of scientific works (Part 4). Lviv: Ukrainian Catholic University, 146–167. (in Ukrainian). Колесник, О. (2014). Бабин Яр як місце пам’яті: огляд комеморативних практик і пам’ятних знаків, Acta studiosa historica: збірник наукових праць. Ч. 4. Львів: Український католицький університет, 146–167. ↩

- Karamash, S. (2014). Babyn Yar – in the tragic events of 1941-1943. History and modernity: historical and archival research. Kyiv: KMM, 256 s. (in Ukrainian). Карамаш, С. (2014). Бабин Яр — у трагічних подіях 1941–1943 років. Історія і сучасність: історико-архівне дослідження. Київ: КММ, 256 с. ↩

- Hrynevych, V. & Magochi, P.-R. (Ed.). (2016). Babyn Yar: history and memory. Kyiv: Spirit and Letter, 352 s. (in Ukrainian). Гриневич, В. & Магочій П.-Р. (Ed.). (2016). Бабин Яр: історія і пам’ять. Київ: Дух і Літера, 352 с. ↩

- Grinchenko, G. (2016). Oral stories about the Holocaust in Ukraine and peculiarities of their interpretations, Oral history of the (un)overcome past: event – narrative – interpretation: Proceedings of the international scientific conference (Odesa, October 8-11, 2015). Kharkiv: KhNU named after V. N. Karazina, 83–91. (in Ukrainian). Грінченко, Г. (2016). Усні історії про Голокост в Україні та особливості їхніх інтерпретацій, Усна історія (не) подоланого минулого: подія – наратив – інтерпретація: Матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції (Одеса, 8-11 жовтня 2015 р.). Харків: ХНУ ім. В. Н. Каразіна, 83-91; Grinchenko, G. (2016). Babyn Yar in oral history, Babyn Yar: history and memory; V. Hrynievych, Magochi P-R (Ed.). Kyiv: Spirit and Letter, 191–216. (in Ukrainian). Грінченко, Г. (2016). Бабин Яр в усній історії, Бабин Яр: історія і пам’ять. Київ: Дух і Літера, 191-216. ↩

- Shchupak, I. (2016). Lessons of the Holocaust in Ukrainian historical science and education: from narrative to understanding and raising the public question of repentance (to the 75th anniversary of the Babyny Yar tragedy), Ukrainian Historical Journal, 4, 152–172; 5, 176–201. (in Ukrainian). Щупак, І. (2016). Уроки Голокосту в українській історичній науці та освіті: від наративу до осмислення й постановки суспільного питання про покаяння (до 75-ї річниці трагедії Бабиного Яру), Український історичний журнал, (4), 152-172; (5), 176-201. ↩

- Medvedovska, A. (2016). The Holocaust in Ukraine in public opinion of the late 20th – early 21st centuries (Extended abstract of Candidate’s thesis). Dnipro, 20 s. (in Ukrainian). Медведовська, А. (2016). Голокост в Україні в суспільній думці кінця XX – початку XXI ст.: автореф. дис. канд. іст. наук: 07.00.01. Дніпро, 20 с.; Medvedovska, A. (2023). Is there no such thing as someone else’s pain? The Holocaust in Ukraine in public opinion in the second half of the 20th – early 21st centuries. Dnipro: Tkuma; “Lira LTD”, 276 p. (in Ukrainian). Медведовська, А. (2023). Чужого болю не буває? Голокост в Україні в суспільній думці другої половини XX – початку XXI ст. Дніпро: Ткума; «Ліра ЛТД», 276 с. ↩

- Radchenko, Yu. (2016). Babyn Yar: a site of massacres, (dis)remembrance and instrumentalisation, New Eastern Europe, (1), 160–171 or URL: https://neweasterneurope.eu/2016/10/11/babyn-yar-a-site-of-massacres-dis-remembrance-and-instrumentalisation; Sergienko, S. (2019). Babyn Yar: gender and age aspects of survival, Holocaust and Modernity, (1), 75-101 (in Ukrainian). Сергієнко, С. (2019). Бабин Яр: гендерні та вікові аспекти виживання, Голокост і сучасність, (1), 75-101; Borovyk, M. (2018). «Our Golgotha»: The tragedy of Babi Yar in the «Kyiv notes» of Iryna Khoroshunova, Bulletin of KNU, series: History, (137), 5–8. (in Ukrainian). Боровик, М. (2018). «Наша Голгофа»: Трагедія Бабиного Яру у «київських записках» Ірини Хорошунової, Вісник КНУ. Серія: Історія, (137), 5–8; Hrynevyс, V. (2021). A disputed historical site Babi Yar as a Ukrainian memorial landscape, Osteuropa (Stuttgart), (1), 63-86; Radchenko, O. (2022). Dr. Arthur Boss: “I had to translate near the site of the shootings in Babyn Yar”, From the archives of the VUCHK-GPU-NKVD-KGB, (2), 177-201. (in Ukrainian). Радченко, О. (2022). Доктор Артур Босс: «Я повинен був перекладати поблизу місця розстрілів у Бабиному Яру», З архівів ВУЧК-ГПУ-НКВД-КГБ, (2), 177-201. ↩

- Mankoff, J. (2004). Babi Yar and the Struggle for Memory, 1944-2004, Ab imperio, (2), 393–415; Clowes, E. (2005). Constructing the Memory of the Holocaust: The Ambiguous Treatment of Babi Yar in Soviet Literature, Partial Answers Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, (3), 153–182; Lower, W. (2007). From Berlin to Babi Yar: The Nazi War against the Jews, 1941-1944, Journal of religion & society, (9). URL: https://cdr.creighton.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/4c532395-9f24-4ef4-badf-e16533421004/content; Peterson, J. (2011). Literations of Babi Yar, Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 46(4), 585–598; Hausmann, G. (2016). 75 Jahre Babyn Jar: Sowjetische und postsowjetische Kontroversen um einen Gedenkort in Kiew von 1945 bis heute, Erinnerungskulturen: Erinnerung und Geschichtspolitik im östlichen und südöstlichen Europa. URL: https://erinnerung.hypotheses.org/647; Naimark, N. (2017). The many lives of Babi Yar: one of the blackest chapters of World War II: the German massacre of Kyiv’s Jews. The horror of Babi Yar, suppressed in the Soviet era, may be finding its proper place in European memory at last, Hoover digest, 176; Martin, B. (2018). Babi Yar, Emulations (Imprimé), (12), 67–79; Davies, F. (2021). Babyn Jar vor Gericht Juristische Aufarbeitung in der UdSSR und Deutschland. Osteuropa (Stuttgart), 1(2), 23-40; Berkhoff, К. (2021). Aussage in der Heimat der Täter Dina Proničeva im Callsen-Prozess, Osteuropa (Stuttgart), 1(2), 41-46; Petrovsky-Shtern, Y. (2021). Ein Tag, der die Welt veränderte: Ukrainer, Juden und der 25. Jahrestag von Babyn Jar. Osteuropa (Stuttgart), 1(2), 87-115; Altares, G. (2022). La matanza de Babi Yar, el momento en que el Holocausto avanzó hacia el exterminio total, Raíces: revista judía de cultura, (131), 68–69. ↩

- Ionescu, А. (2022). Layers of Memory in Kuznetsov’s and Trubakov’s Babi Yar Narratives, Eastern European Holocaust Studies. URL: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/eehs-2022-0012/html?srsltid=AfmBOoqs4XrQkSjVTETPe3WcNIhAqJz3CMcLdC-YcfcbURwn0rZTmqzq, https://doi.org/10.1515/eehs-2022-0012. ↩