There’s a hole in one of the socks near where the toes should be. Is that where an elderly female prisoner deliberately knitted a defect? Is it traces of use? Or is it just because the socks were knitted eighty years ago? Other than the hole, the socks have held up well. They are a little dirty, perhaps, but that’s understandable considering what they went through to get here. Knitted in a Nazi concentration camp in the early 1940s, smuggled out of the camp by a prisoner liberated by the Red Cross in the spring of 1945, before the war was officially over, and carried to Sweden, where they were kept and carefully preserved at various locations, and for the last 30 years, displayed in a glass case, as a museum artefact. Even now, looking at them through the glass, they appear soft and warm rather than coarse and uncomfortable. It’s hard to imagine they were knitted in such a way to cause pain to the wearer. How could these socks have sabotaged the Nazi war effort, as the cards in the display case explain? If only we could pull on one of the frayed ends of the black and white yarn around that hole and unravel the story of this pair of socks – “sabotage socks,” as they have been called. Our purpose in this blog post is to begin to do just this, at least metaphorically.

In the following, we will examine the socks – which are part of the so called “Ravensbrück collection” at the local history museum Kulturen in Lund (hereafter Kulturen) in southern Sweden, where they are on display as part of a permanent exhibition – as a primary source, focusing as much on what we can learn from their materiality as what we can learn from other kinds of sources. Considering physical objects in relation to sources such as archival documentation, oral histories, and secondary literature, we stress the significance of the socks as sources of knowledge beyond the meaning inscribed on them. As museologist Susan M. Pearce writes, the naming of objects is typically understood as what brings them into being and defines them in relation to social reproduction. She argues, however, that material culture “has an independent social existence of its own which contributes to social reproduction.”1 Without contesting or attempting to refute the contextualization of the socks in the Kulturen collection as sabotage socks, we are interested in what insight their “social life” can give us that naming has not.2 Our findings provide insight into the layers of meaning behind this and other material artefacts in museum collections related to the Holocaust.

What is Said About the Socks

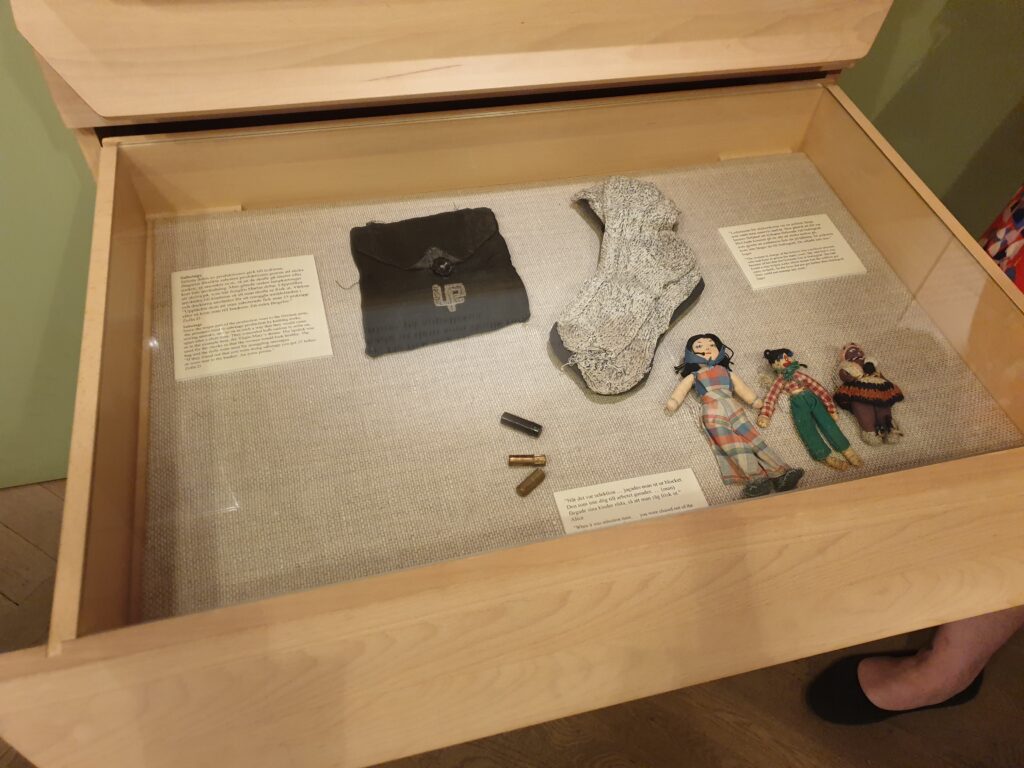

The socks in question are part of the Kulturen exhibition titled, in Swedish, Att överleva – Röster från Ravensbrück (To survive – Voices from Ravensbrück). The small but poignant exhibition features objects smuggled out of Nazi concentration camps by liberated concentration camp prisoners who were brought to Sweden by the Red Cross for medical care in the spring of 1945.3 Most objects are in drawers that visitors can pull out to reveal objects placed together thematically, divided into nine themes The drawer labeled “Sabotage” reveals a dark fabric pouch with the embroidered initials “LP,” three metal lipstick tubes, three small dolls made of scrap fabric, and a pair of knitted socks. The main description card in the drawer – also titled “Sabotage” and written in Swedish and English – includes a statement made by Zofia D., a former political prisoner, in an interview made by the museum in the late 1990s: “Since the major part of the production went to the German army, the prisoners tried to sabotage production by knitting socks, sewing anoraks, and so on in such a way that they would come apart after a short time.” Next to the socks is a description card with a quote in Swedish and English, attributed to a Swedish woman named Inger, also dating to the late 1990s, which reads:

The leader of the knitters was a political prisoner, who had been in prison for many years. She said that it was because of her that the Germans lost at Stalingrad. She had found a way to knit the socks which meant the soldiers got sores on their heels. So the boys did not get further than Stalingrad. They could not manage any more.

These statements begin to provide visitors to the exhibition an understanding of one aspect of women’s resistance in Nazi concentration camps. We know from a variety of sources that knitting socks – or stockings, as they are usually referred to in the accounts of former concentration camp prisoners – for SS soldiers was a form of forced labor assigned to women known as Strickerinnen, who were typically elderly or otherwise unable to do more strenuous forms of forced labor.4 In this way, the skill of knitting could be deployed as a survival tactic. As with all forced labor, the knitters were generally closely supervised by guards, worked long hours, and were expected to fulfill quotas.5 They also found subtle ways to sabotage production. While knitting socks for the SS, they did this by making the socks defective with the aim of creating wounds to the feet of marching soldiers that would disable them, up to the point of causing lethal infections.6

Knitted goods and other items intended for the SS are parts of other museum collections. However, in the other examples, the yarn used was typically wool.7 This is where the materiality of the socks in the Kulturen collection begins to speak for itself. An inventory in the archive describes the socks in the collection as, “SOCKOR stickade, svart och vitt silke??” (translation: SOCKS knitted, black and white silk??).8 The question marks remind us that we do not know for sure whether the material is silk, only that it is soft and silky. But other questions are raised by this aspect of the socks’ materiality, not to mention their contextualization as sabotage socks.

Another piece of archival evidence raises additional questions about the socks. An undated, handwritten note reads (in Swedish translation), “Sabotage socks from Ravensbrück 1943. Gift for the name day of Mrs. Ludwika Broel Plater given by French ‘Strickerinnen’, whose boss she [Broel-Plater] was.”9 This note gives us a tantalizing glimpse of the social life of these socks, especially when considered alongside the material from which they were made. Between these two contextual clues, we begin to see a different aspect of the socks than the type of sabotage described in the exhibition. This is the thread we will pull to start unraveling the social life of the socks.

What the Socks “Say”

Without any context, the socks are rather unremarkable. But, of course, in their present form, as knitted socks, they are already part of a context. Knitting is commonly associated with a simple everyday life, femininity, and – often – old age. Then there is their physical appearance: black and white mélange, fraying at the toes, a bit dirty, and relatively small. A skilled knitter might say that the quality of the knit is quite good, though perhaps a bit loose, and maybe also tell us about the stitches used. Since neither of us are knitters – skilled or otherwise – we cannot provide this type of expert insight. But we can unravel their materiality in other ways. To begin with, we know that they were knitted using a soft yarn, possibly silk, rather than a more durable wool. This aspect of the socks’ materiality is documented in the written source material but is also sensually and visually obvious. The socks’ material speaks to us of warmth and comfort, not pain.

Writing about the material artefacts in the Kulturen collection, scholar Johanna Bergqvist Rydén has drawn attention to how female prisoners of the Nazis would have understood sabotage in the same sense as did the Nazi administrators, as “behavior or actions which were not sanctioned.”10 In this sense, sabotage would not be limited only to disrupting production or causing pain to SS soldiers. It could also mean using materials meant to benefit the Nazi war machine for some other purpose – particularly one that did not help the Nazis. Various sources tell us that prisoners involved in the production of clothing and other goods intended for the Nazi war machine sometimes diverted the materials they worked with for some other purpose.11 Likewise, as Rydén emphasizes, clothing and shoes – including socks – sourced in a variety of clandestine ways were also a form of sabotage since the prisoners were denied these basic and crucial necessities.12

Considering the quantity of clothing and other material taken from prisoners entering Nazi concentration, labor, and extermination camps that the prisoners were forced to sort for Nazi use, luxury textiles such as silk would not have been outside the reach of prisoners willing to risk their lives to smuggle these items into the camp population. In addition, some prisoners working in textile production would even have had access to raw materials such as the fur from Angora rabbits, a very soft type of wool with what is described as a silky texture.13 Taking into consideration former prisoners’ accounts that supervision of forced labor was sometimes lax, it is easy to see how materials could be diverted for purposes other than the Nazi war machine. In other words, sabotage in the sense of creating something that defies dehumanization – a silky pair of socks.

The Social Life of Socks

Zofia’s and Inger’s statements that contextualize the socks in the Kulturen exhibition were inspired by looking at them many years after they were knitted in Ravensbrück. They are inscriptions that are part of the social life of the socks. By “the social life of the socks,” we mean how “objects work to create our understanding and response – in a word, our social selves.”14 The socks worked affectively on Zofia and Inger, who associated them with a particular type of sabotage, either through firsthand experience as a Strickerin in Zofia’s case or secondhand knowledge in Inger’s. Their response to the socks provided the social context that framed them in the exhibition. However, as Pearce emphasizes, “material culture does not match language in a one-to-one sense, still less in a one-in-relation-to-one sense.”15 This can be seen in how another Polish Strickerin, Elżbieta Popowska, referred to knitting and knitted socks in a poem she wrote during her imprisonment in Ravensbrück called Knitter in Despair (Sztrikierynka w rozpaczy). The first six rhymes read in translation:

Would I know

When I’d die

Would I buy

An oak coffin.

On this coffin.

Tiny garlands, little stockings,

So they may know

That I’m a tiny little knitter.

I leave the knitting needles

In the will,

To a stocking unfinished

At the heel.

None of them will cry

At my funeral.

She will have the whole bed

To herself now.

The poor woman died

In the prime of her life.

She will be better off

In that other world.

And when her ashes

Rest in a pit

All over the world

We will knit!

(…)16

Popowska’s poem draws out other aspects of the social life of knitted socks, or “stockings,” in Nazi concentration camps. The “little stockings” decorating her imagined coffin symbolize her identity as a “little knitter” condemned to death by labor. She bequeaths the unfinished socks and her knitting needles to the surviving Strickerinnen, who must complete her unfinished work and ultimately perish similarly. This example emphasizes how socks knitted by forced laborers were (and still are) meaningful in various ways.

Through the metaphorical unraveling of the socks at Kulturen, we can begin to understand them beyond their current contextualization as “sabotage socks” of a specific type. That they were made of a silky material and were given as a gift, provides alternative contextual clues as to the social life of these socks and raises questions like: Would socks intended for the SS – with or without defects – be knitted using silk or something akin to it? Would socks intended to injure the wearer be given as a gift? Our point, however, is not to argue against the contextualization as “sabotage socks” but rather to tease out layers of meaning.

Although we do not have at our immediate disposal Ludwika Broel-Plater’s thoughts or feelings about the socks and their meaning as a gift to her, we do know that the socks are in the Kulturen collection because she preserved them, along with many other material objects.17 Broel-Plater’s part in the social life of the socks can be partly understood by how she kept them safe throughout her imprisonment and after. In doing so, she ensured they would outlive her. But why? What knowledge did she think they would convey? Why did she make sure they became part of a collection?

To suggest that she kept them only because they were a gift seems to us too simple an explanation. Even the word “gift” risks banality as it conceals all the complexities and risks of the action to make, give, receive and preserve something so valuable. In circumstances where prisoners of Nazi concentration camps typically wore wooden clogs in summer and winter and rarely socks, a pair of silky socks would have been a valuable gift that could save your life. One could argue that making the socks was a form of sabotage as great as knitting a pair of defective wool socks for a member of the SS.18 Each form of sabotage had its place: the defective wool socks for the SS and the silky, functional socks for the fellow inmate. Each form of sabotage was also equally risky. Accordingly, we also must consider what it means to give and receive the socks under such conditions. A gift can be given out of love and respect or gratitude, but it can also be a transaction for security for oneself or one’s loved ones. We do not know the details of the social dynamics in gifting the socks to Ludwika Broel-Plater, only that they were an important part of social interactions in a place of despair.

The only thing we know for certain is that Broel-Plater went to great lengths to ensure the preservation of these socks. Perhaps she understood what Pearce articulates about the centrality of objects to human social life: “Society as we understand it would not exist without them.” At the same time, “objects are meaningless without social content.”19 The preservation of the socks provides a wormhole to life in Nazi concentration camps. A sensory portal that differently affects those who gaze through it. The social life of the socks in the Kulturen collection, like all other materiality, is infinite and, therefore, never fully knowable. This is partly because, as anthropologist Webb Keane argues, “the qualities bundled together in any object will shift in their relative salience, value, utility, and relevance across contexts.”20

Reassembling the Socks

Considering the materiality of the “sabotage socks” in the Kulturen collection alongside the sources, we have demonstrated that they have more to tell us about their social life. Without contesting that they were almost certainly knitted in Ravensbrück by Strickerinnen, who knitted defective wool socks intended for the SS, we argue that these socks served other purposes besides deliberately injuring Nazis. Given as a gift, these socks were knitted from the finest material that concentration camp inmates could illicitly procure. In a sense, they preserve not only the person who knitted them but also all the Strickerinnen. Moreover, they preserve the act of knitting them, a lasting impression of hands in motion, hands forced to labor and create for evil but also hands determined to create something that resists that evil. Received as a gift, they may have been worn despite the dangers involved in doing so. They survived destruction because they were valued by both the giver and the receiver. As the “little stockings” that keep the memory of the “little knitters” alive, they are both memorial and testimony to suffering, resistance, survival, and death. In short, everything about these socks was not sanctioned by the Nazis, making them sabotage socks of the highest order.

This research was conducted as part of the project Swedish Remembrance of the Holocaust: Museums, Materiality and Politics, funded by the Swedish Research Council (Project-ID 2022-02011_VR).

- Susan M. Pearce, Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study, (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), 21-22. ↩

- Ibid 22. ↩

- A historical overview may be found in, e.g., Steven Koblik, The Stones Cry Out: Sweden’s Response to the Persecution of the Jews, 1933-1945 (New York: Holocaust Library, 1988). ↩

- See, e.g., Archive of the Pilecki Institute, Chronicles of Terror, (Zeiske) Wojciecha Buraczyńska, Testimony from court/criminal proceedings from 01.10.2640, https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=1364 (Accessed 06.09.2024), original: Institute of National Remembrance, GK 182/164, 4. ↩

- See, e.g., ibid, (Wilgat) Krystyna Czyż, Testimony from court/criminal proceedings from 01.10.2420, https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=1370 (Accessed: 06.09.2024), original: Institute of National Remembrance, GK 182/164, 5-6. ↩

- Jack G. Morrison, Ravensbrück: Everyday Life in a Women’s Concentration Camp 1939-1945 (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2010), 233. ↩

- See, e.g., Yad Vashem, “Sweater that Gucia Wald Teiblum knitted in the Bergen-Belsen DP camp,” https://www.yadvashem.org/artifacts/featured/liberation/sweater-bergen-belsen.html (Accessed 06.09.2024). ↩

- Kulturen Arkiv, “Deposition på Kulturen, Lund, hösten 1966,” 8. ↩

- Translated from the Swedish original: “Sabotage socker från Ravensbrück 1943. Gåva till namnsdagen av Ludwika Broel Plater, gåva av franska ’Strickerinnen’, vars chef hon var.” Kulturen CCIX:20. ↩

- Johanna Bergqvist Rydén, “When Bereaved of Everything: Objects from the Concentration Camp of Ravensbrück as Expressions of Resistance, Memory, and Identity,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22, 511–530 (2018), 517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-017-0433-2. ↩

- See, e.g., Morrison 144; Krzysztof Dunin-Wąsowicz, Resistance in the Nazi Concentration Camps 1933-1945 (Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers, 1982), 250. ↩

- Rydén, When Bereaved of Everything, 517. ↩

- See, e.g., Interview, Alice Wolfhörndl, Kulturen Arkiv 209.1.17. ↩

- Pearce, Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study, 23. ↩

- Ibid 22. ↩

- Elżbieta Popowska, “Knitter in Despair,” Translated from Polish. Voices from Ravensbrück: An Art, Memorial and educational project by Pat Binder, https://universes.art/en/voices-from-ravensbrueck/forced-labor/popowska-strickerin (Accessed 05.09.2024). ↩

- See, e.g., KM 88992, Carlotta: Databasen för museisamlingar, Kulturen, https://carl.kulturen.com/web/object/186658 (Accessed 06.09.2024). There may be such a description in her extensive but unfinished witness testimony and other personal materials held in the Lund University Library’s archive. However, these documents are in Polish and require professional translation. We are among those who would like to see these materials digitized, transcribed, and translated. ↩

- Rydén, When Bereaved of Everything, 519. ↩

- Pearce, Museums, Objects, and Collections: A Cultural Study, 21. ↩

- Webb Keane, “Signs Are Not the Garb of Meaning: On the Social Analysis of Material Things,” in Daniel Miller (ed.), Materiality (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2005), 188. ↩

Kate E

This was a fabulous article. There is new information about the “sabotage socks” to help me further contextualize the visual arts project that I am currently working on. I’m a fiber artist and printmaker, among other things, so the women’s work aspect I created a site specific installation based on accounts at Ravensbruck in 2005. I then had the honor of visiting the concentration camp in Furstenburg about a year ago. I feel like things have come full circle. Feel free to get in touch!