When war was declared between Germany and the United Kingdom, September 3, 1939, all Germans and Austrians living in the UK were automatically classified as ‘enemy aliens’.1 For the first time in the historiography of this subject, this article maps where Germans and Austrians over the age of 16 were resident in the United Kingdom in September 1939. This article aims not only to explore where these Germans and Austrians – who were mostly refugees from Nazi oppression – lived in Great Britain, but also to examine the decisions of the tribunals established by the British government to classify ‘enemy aliens’ by their perceived threat to national security. To do this, sources from The UK National Archives 2 have been used to map both where refugees lived in 1939, as well as to see whether or not areas with high concentrations of Germans and Austrians received more generous treatment by the tribunals. Essentially, did where an ‘enemy alien’ live at the outbreak of war affect their wartime experience?

The British government knew the majority of Germans and Austrians in the United Kingdom in the 1930s and 1940s were refugees from Nazi oppression so did not want to institute a policy of mass internment as they had during the First World War, when all male Germans aged 16 to 42 were interned.3 To avoid this, tribunals were created to interview all ‘enemy aliens’ and to put them into three categories:

A – a threat to national security requiring immediate internment;

B – at liberty but placed under certain restrictions including not being able to travel more than 5 miles from their place of residence;

C – Considered a genuine refugee of Nazi oppression and remaining at liberty.

In principle, this was a system to protect refugees from Nazi oppression who had found sanctuary in the United Kingdom from internment.

Category B and C ‘enemy aliens’ were initially left at liberty, however, after German advances across Europe in May 1940 and the threat of a German invasion of the British mainland became a very real possibility, public hysteria demanded a policy of mass internment. On May 12, 1940, ‘enemy aliens’ living near the East or South coast of Britain were arrested, followed by category B men on May 16, 1940, category B women on May 28, 1940, and finally, from June 25 into mid-July 1940, category C men. Tribunal categories determined which camps an individual was taken to and could also affect whether an individual was deported to camps in Canada or Australia, which ultimately affected the amount of time spent in detention.

Governmental guidance to tribunals

All 120 tribunals established in the UK in September 1939 were provided with the same instructions for how they should operate. These were provided in a written document called the “Home Office Memorandum for the Guidance of Persons Appointed by the Secretary of State to Examine Cases of Germans and Austrians”.4 This guidance noted that:

1. Germans and Austrians in this country, being nationals of a state with which His Majesty is at war, are liable to be interned as “enemy aliens”, but most of the Germans and Austrians now here are refugees from the regime against which this country is fighting, and many of them are anxious to help the country which has given them asylum. Others have been here a long time and have formed such ties and associations here that their sympathies are with this country rather than their country of origin. Some of them have British-born wives and British-born children. It would, therefore, be wrong to treat all Germans and Austrians as though they were enemies.

2. There are, however, Germans and Austrians who are not friendly to this country and might, if they had the opportunity, act in a manner prejudicial to the public safety or the defence of the realm. Those whose suspicious activities have been under observation have been already interned, but to avoid risks and to supplement the information already available to the authorities, it has been decided to review the case of every German and Austrian over the age of 16 for the purpose of considering whether on grounds of national security he or she ought to be interned.5

Tribunals were expected to assess information provided by the police, the Home Office, the Security Services (MI5) and refugee charities based at Bloomsbury House in London. Officially, the tribunals were advisory rather than legal bodies, meaning they did not have to work under the constraints of evidence and could use their own judgement for assigning categories to ‘enemy aliens’. This created a huge amount of inconsistency depending on those in charge of the tribunal and how they interpreted the guidance.

Tribunals did not have to interview every individual in person, but they were advised that in any case “where the tribunal thinks internment may be necessary, the alien should be interviewed before a decision to intern is endorsed on his certificate”. Furthermore, “unless the tribunal, after considering the information available, decides to exempt the alien both from internment and from the special restrictions applicable to ‘enemy aliens’, the alien should be allowed if he so wishes to appear before the tribunal and to make representations”.6

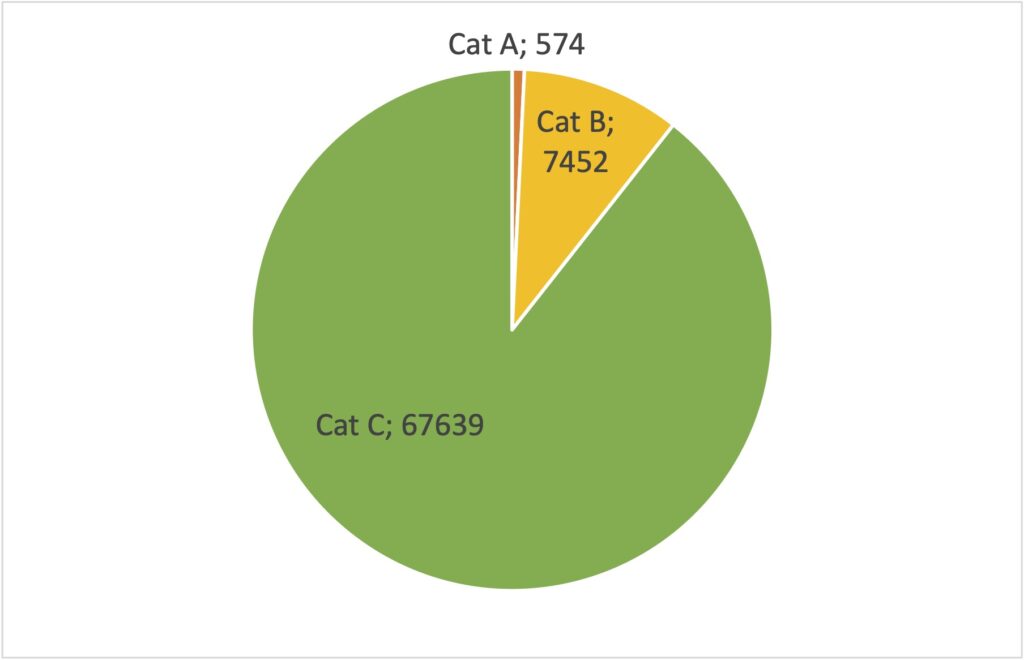

Overall, some 75,665 individuals over the age of 16 went before enemy alien tribunals in the United Kingdom between September 1939 and January 1940. Approximately 22 percent of these were written on lists called ‘non-refugee’ with 78 percent listed as ‘refugee’.7 There were various reasons for these two lists, the main one being that the British generally did not consider Germans or Austrians who arrived in the UK before Kristallnacht to be refugees. This was a flawed premise and, while it was true that not all Germans and Austrians in Britain were refugees, the vast majority had in fact fled the Nazis due to persecution. This classification should, therefore, be treated with a certain degree of wariness. This ‘refugee’ and ‘non-refugee’ classification was a separate listing carried out before the tribunals made their A, B and C categorisations.

Refugee population in the UK in 1939

To map where the refugee population lived in Britain in 1939 I have used data compiled retrospectively by the British government in 1941, and I have created the first visual representation of this data based on how many individuals were seen by the regional tribunals across Great Britain.9 Although not all the data survives, enough data exists to give a strong indication of where these refugees were living on the outbreak of the Second World War. The data that survives comes from British Home Office files. The government kept records of the numbers of foreigners arriving in Britain as well as requiring all foreign nationals to register with their local police force, meaning that they were the most likely to have as complete a set of data regarding Germans and Austrians as possible. Other sources, such as the records of refugee charities, do not survive in entirety and, unlike the government records, only focus on specific groups of refugees, rather than all foreigners. The data used in this study is, therefore, the most accurate that can be gathered on this topic despite its limitations. Government statistics are not an infallible source, and even within Home Office files there are typographical errors and minor inconsistencies in the numbers noted between pages of the same file. Many of the typographical errors are calculation errors, and these have been corrected in this study by recalculating all totals within an Excel spreadsheet.

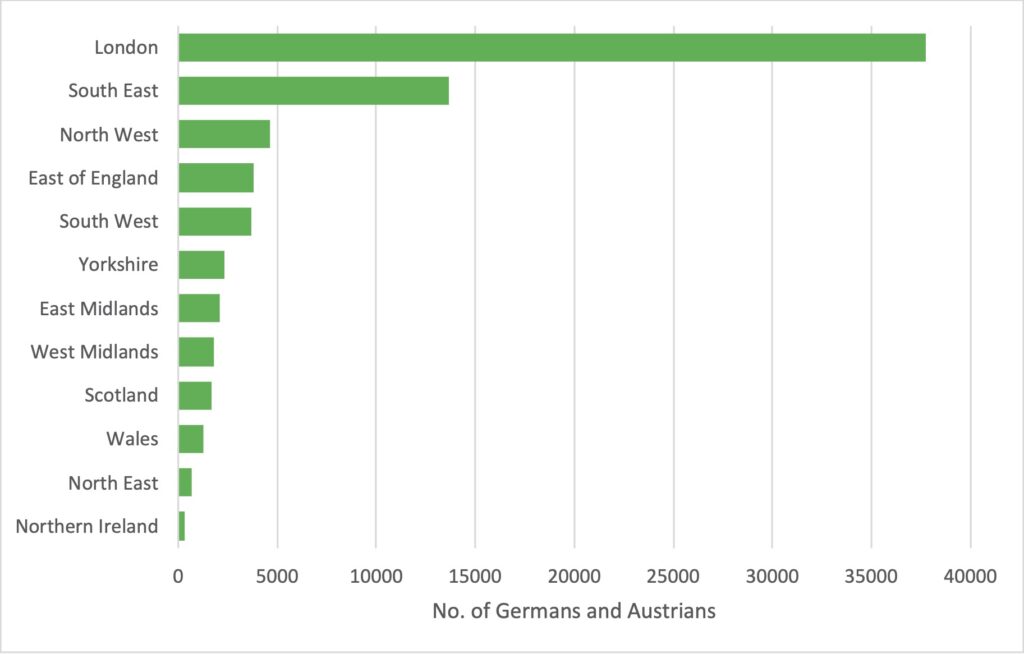

When analysed by UK geographic regions, it is clear to see that the vast majority of Germans and Austrians (51 percent) were located in the Greater London area, with the second largest concentration (19 percent) living in the South East (see Figure 2). Only 30 percent of Germans and Austrians lived further away from London and the South East, with the smallest number (0.4 percent) located in Northern Ireland.

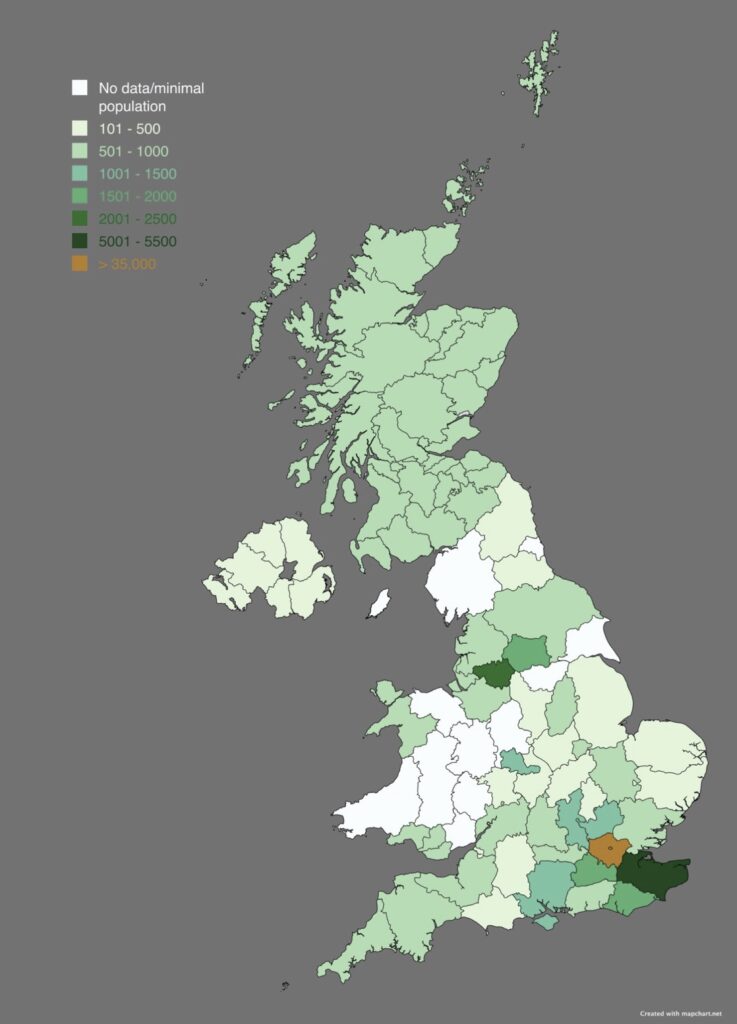

This numerical breakdown is not sufficient to demonstrate where the larger refugee populations were located – were they, for example, evenly distributed across each region or were there areas of higher concentration within the regions? Figure 3 shows in more detail where Germans and Austrians were living in Britain in late 1939.

All foreigners had to register with the police on arrival in the United Kingdom, which is how the British authorities knew how to locate ‘enemy aliens’ and invite them to the tribunals.10 There were approximately 120 tribunals in total, some covering huge areas, while some towns and cities had multiple tribunals. White areas on the map in Figure 3 represent areas where no tribunals were convened, suggesting either no refugees, or such a negligible number they were assigned to other geographic regions; the darker the colour, the more Germans and Austrians who lived in that region. We can see that outside of the highest concentration of Germans and Austrians in Greater London, Kent was the next most populated region, followed by high numbers in Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, Surrey and East Sussex. The high numbers in Kent relate to the Kitchener Refugee Camp in Richborough, near Sandwich. This was a rescue scheme organised through the Central British Fund for German Jewry that brought around 4,000 male refugees to Britain who had been arrested by the Nazis after Kristallnacht.11 Kitchener Camp was so large it had its own tribunals for the 3,303 still living there in September 1939 and 99.5 percent of those who came before them were categorised as C. Excluding Kitchener Camp, Kent would have been likely to have had a similar concentration of Germans and Austrians as Surrey, West Yorkshire or East Sussex.

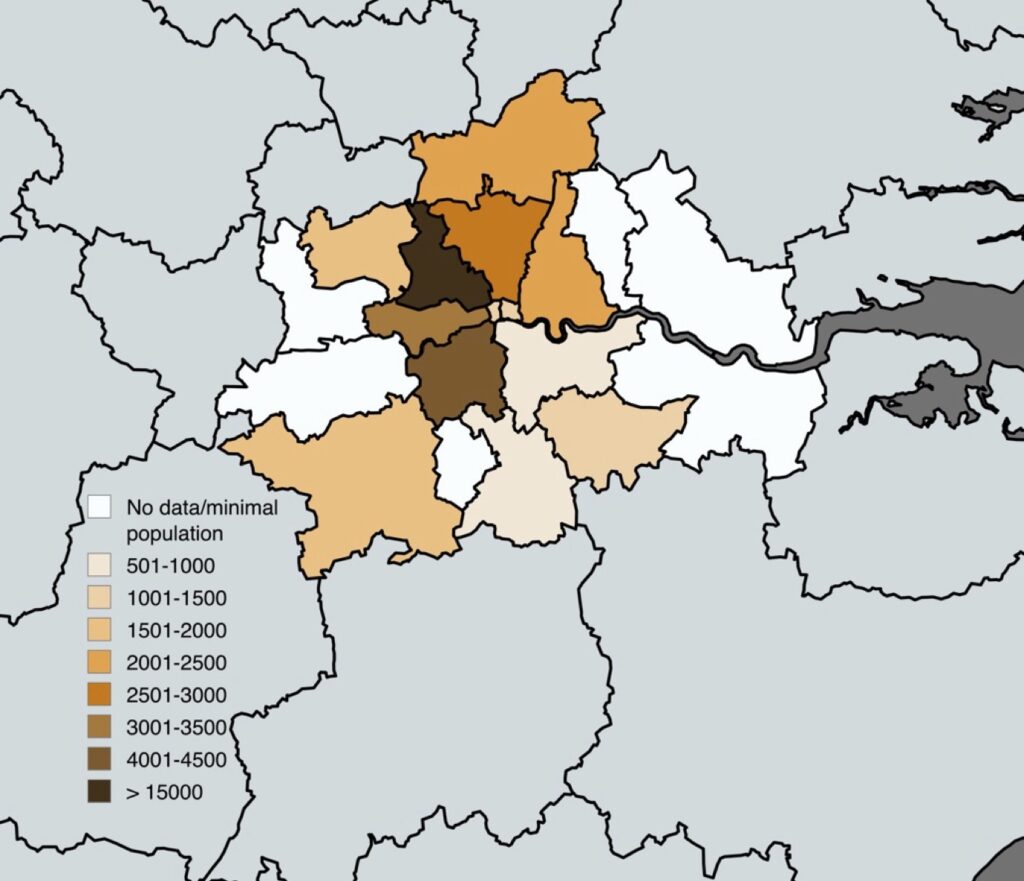

The highest concentration of Germans and Austrians in the Greater London area, as shown in Figure 4, was unsurprisingly located in the North West of London, which had a large Anglo-Jewish population and, therefore, was a natural destination for Jewish refugees from Nazi oppression. The numbers in the North West of London far exceed any other London region, with over treble the number of the next most populated area, the South West of London.

Overall, the maps provide new insights into the population distribution of Germans and Austrians in late 1939. Large concentrations of Germans and Austrians settled in London and the South East, which is to be expected given the locations of the refugee charities and large number of employment opportunities available in this area. The North West of England was also a popular destination, particularly focused around the cities containing large Anglo-Jewish populations including Manchester and Leeds, as well as Birmingham. The distribution of Germans and Austrians in less populated areas was mostly due to refugees finding employment in domestic service, gardening, nursing, agricultural training schemes and other similar work, and it is interesting to see how much these individuals were spread across the country.

Geographical differences in tribunal decisions

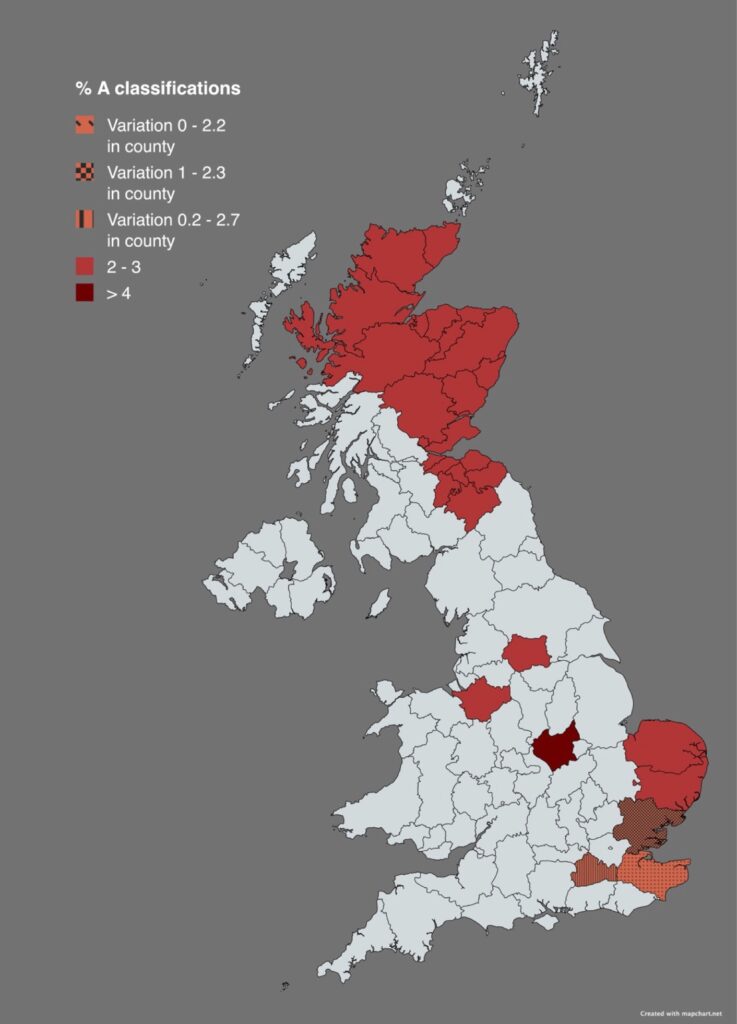

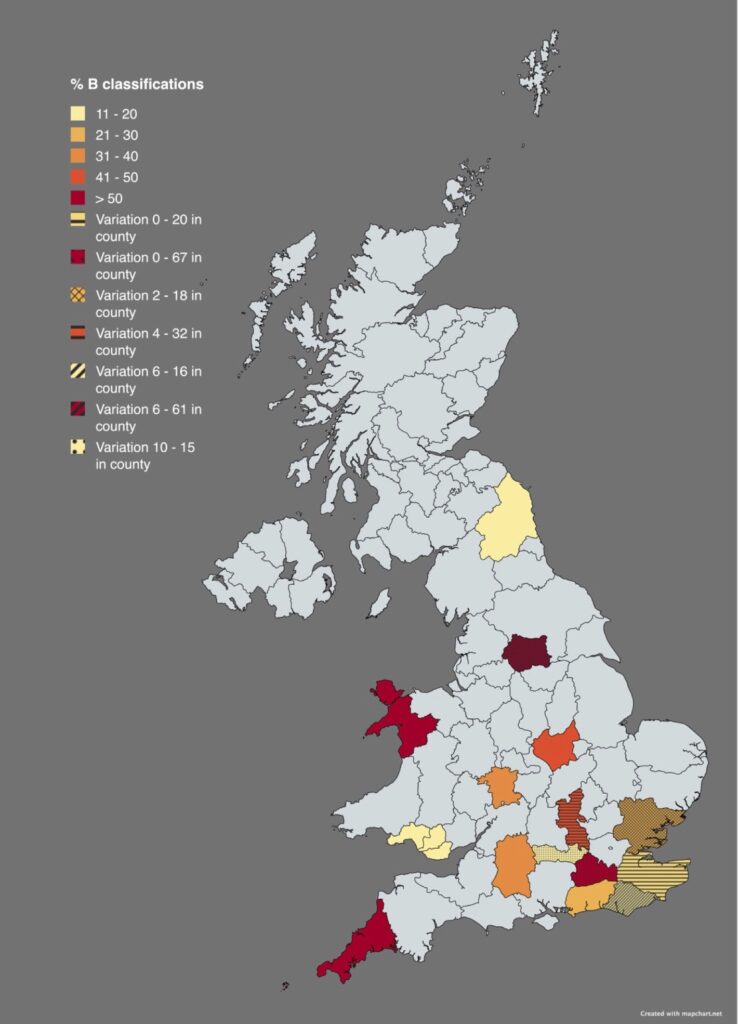

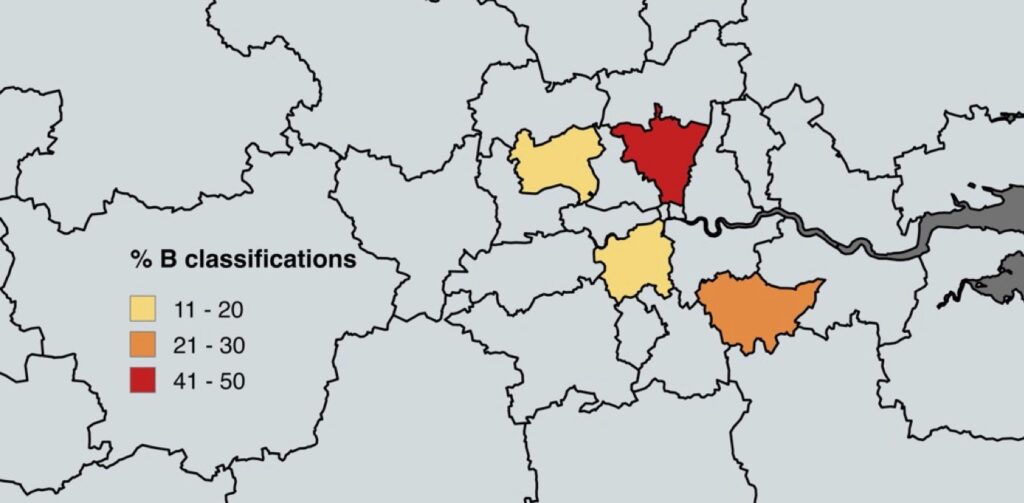

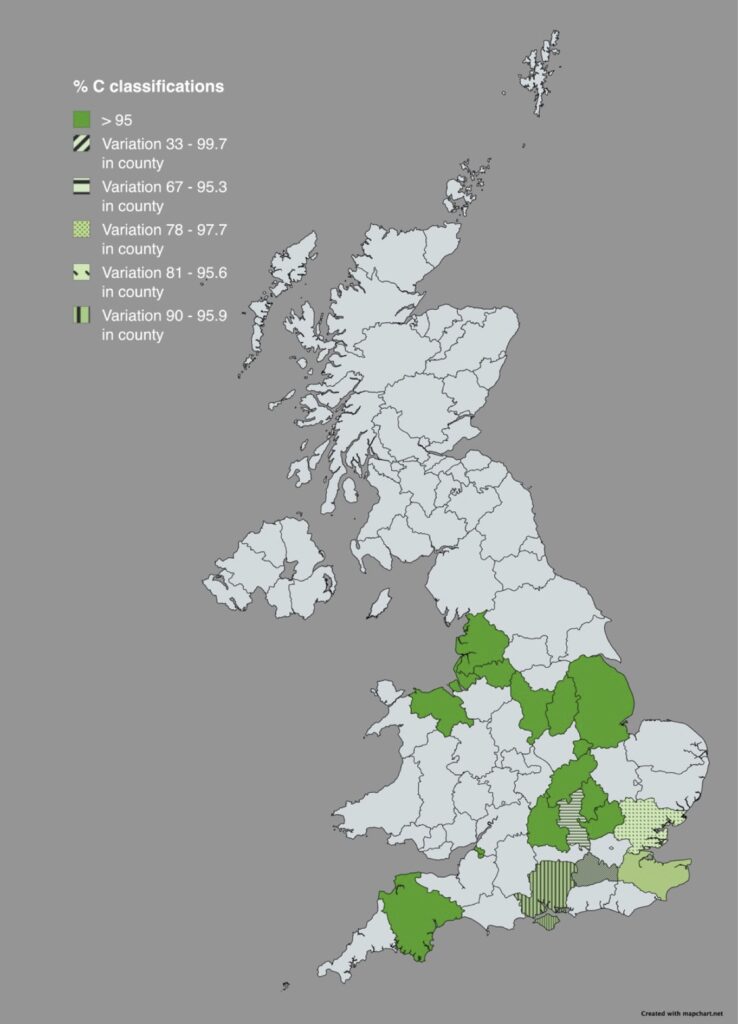

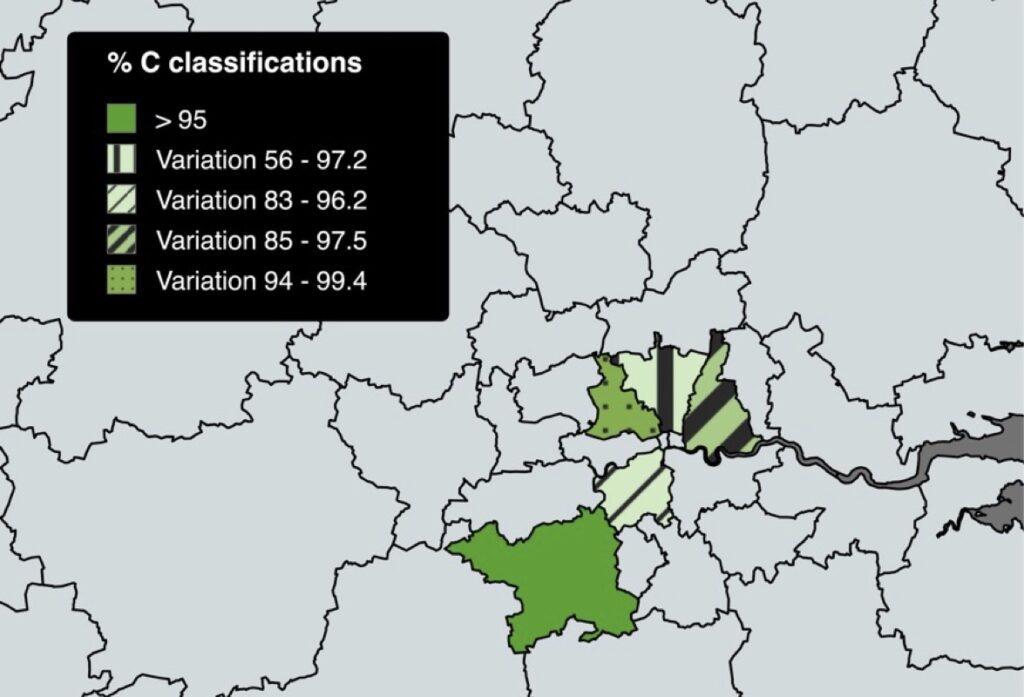

Using the same Home Office data, it has been possible to analyse if the level of refugee population had any influence over the how the tribunals categorised ‘enemy aliens’. Across all tribunals, the average number of category A classifications given was just 0.8 percent, the average number of category B classifications was 11.3 percent, and the average number of category C classifications was 87.8 percent. This article looks at areas which significantly diverged from these averages, specifically tribunals that classified 2 percent or more of ‘enemy aliens’ as category A, who classified 15 percent or more of ‘enemy aliens’ as category B, or more than 95 percent of ‘enemy aliens’ as category C. Some counties had too many ‘enemy aliens’ to go before just one tribunal, which meant there were several in the same county. Areas with multiple tribunals could vary considerably with their decisions, and this is reflected where there are patterns in the colours in the maps, to show this differentiation.

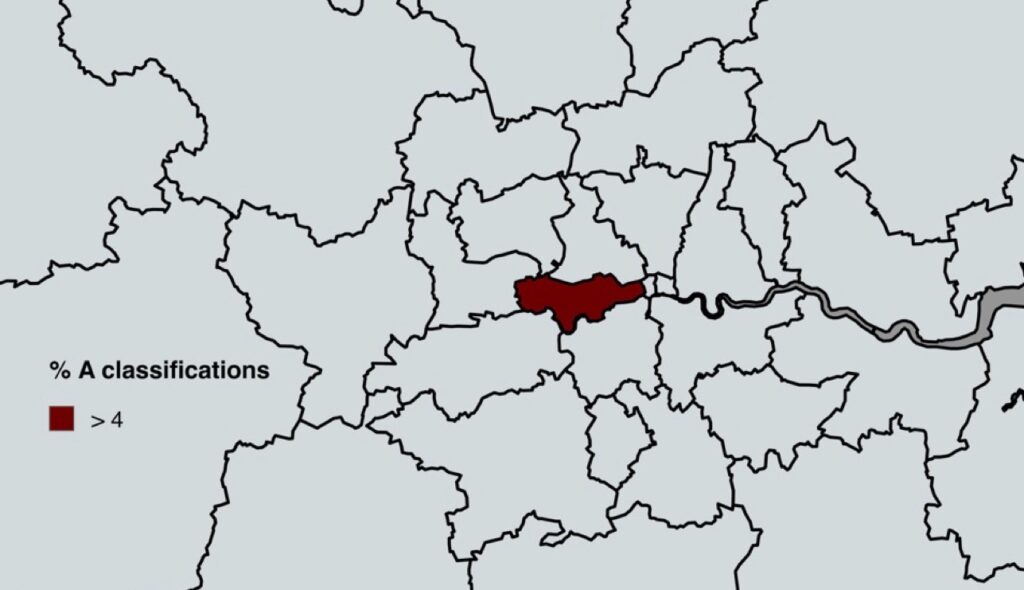

Only two tribunals classified more than 4 percent of those who came before them as category A – Leicester and Metropolitan Police District 5, which covered the area around Paddington in London. Leicestershire contained a very small population of refugees while Paddington contained a large one. Out of the other areas which gave between 2 and 3 percent A classifications, East Scotland, Norfolk and Suffolk housed only a small number of refugees, but Cheshire, West Yorkshire, Surrey, Essex and Kent housed sizeable populations. The only trend in the classifications is that many of these regions were on the East Coast of England and Scotland, areas that became Protected in 1940 because of the likelihood of German invasion in these areas.

In contrast to the category A classifications, there was a lot more variation in areas which gave higher than average numbers of category B classifications. Only 3 areas of the United Kingdom gave significantly higher than average classifications in both category A and B: Canterbury (low refugee population), Leicester (low refugee population), and Leeds (high refugee population). Once again, there were areas in the United Kingdom which housed relatively low numbers of refugees and yet gave out high numbers of B classifications, as well as areas that housed high numbers of refugees and gave out similarly high numbers of B classifications. Areas particularly worth mentioning in terms of the elevated numbers of B classifications include Canterbury (20 percent), Chichester (25 percent), Wiltshire (31 percent), Wycombe (32 percent), Worcester (38 percent), Stoke Newington (42 percent), Leicester (43 percent), Cornwall (51 percent), Gwynedd (55 percent), Leeds (61 percent), and Reigate (67 percent). In these areas it can be seen that the magistrates in charge exercised a considerable amount of caution in how they interpreted the Home Office tribunal guidelines, preferring to be safe rather than sorry, which ultimately led to many more being interned earlier and for longer. In the Greater London area, it is notable that the areas with the highest concentration of refugees did not give excessive A or B classifications.

In regions with large numbers of Germans and Austrians there were usually several tribunals, and the classifications given by these tribunals within a very small geographic area could vary considerably. In Buckinghamshire there were three main tribunals, in Aylesbury, Slough and Wycombe. In Aylesbury, 95.3 percent of those who came before the tribunal were categorised as C, whereas in Slough this figure was 80.4 percent and in Wycombe it was 67.2 percent. In both Slough and Wycombe, the number of B classifications given were significantly above the national average, suggesting that the individual magistrates were more suspicious of foreigners in general. Similarly, in Surrey, there were large discrepancies between the tribunals, the most extreme being from one of the Guildford tribunals classifying 99.7 percent of those coming before it as C while the Reigate tribunal classified a mere 33 percent as C, with 66.8 percent classified as B. The likelihood of ‘suspicious enemy aliens’ being so unevenly distributed within a small geographic area is unlikely and the credible explanation is that these results suggest how widely the tribunals were influenced and led by the magistrate in charge based upon their own personal views and biases. Therefore, as these maps have demonstrated, where an individual lived on the outbreak of war had a significant influence on if and when they were interned, which hugely affected their ultimate internment trajectories.

Tribunal experiences

This type of geographic analysis can also be used as a cross-reference to help anchor personal testimony in the historiography of Second World War internment. How these tribunals were described by Germans and Austrians at the time and in subsequent memoirs sheds light on how the system worked. Combined with the tribunal statistics, it is also possible to now compare these descriptions with the results of the tribunal. Below are four examples to illustrate this point. Opportunities open to Germans and Austrians immigrating to Britain were mostly limited to jobs such as working as domestics or nurses for women (as in the cases of Margot Pottlitzer and Margot Pogorzelski), or as gardeners or agricultural workers for men. For those with money and connections who left Germany in the mid-1930s, it was possible to establish oneself in professional employment, as Ludwig Spiro had done prior to his tribunal. Another way to come to the UK was as a student, such as in Max-Otto Loewenstein’s case. These are a mere sample of tribunal descriptions in order to illustrate how tribunals felt to ‘enemy aliens’ and to compare their experience with tribunal statistics in a given area.

Max-Otto Ludwig Loewenstein, later known as Mark Lynton, was a student in Cambridge at the time of his tribunal. He described his experience as follows:

[The tribunal] was made up of half a dozen reserve officers, all decked out in faded World War I uniforms, and presided over by Judge Thesinger, a reasonably well-regarded judge and brother of a much better known actor. This geriatric gaggle set to in the finest Colonel Blimp tradition: what school had I been to (Cheltenham; very sound), did I play soccer or rugby there (rugby, of course; very good), did I play squash (I did; splendid), was I a member of the Officer Training Corps (forgot it was Cheltenham; silly question, of course, ha-ha)….It went on in that vein until it came to references, and I handed over [General Sir Ernest] Swinton’s [a military historian and the originator of tank warfare in World War I] little note….it was reverently passed from hand to hand…and I was promptly certified as a “friendly alien.” It should perhaps have occurred to me then that a screening process that would theoretically have allowed me to have long telephone chats with Hitler that very night might create problems at some later stage.12Max’s description of the tribunal suggests that the Cambridge tribunal did not look particularly thoroughly into cases and were happy to classify most people as C. However, the statistics show that the Cambridge tribunal was actually below the national average of C classifications with 83.8 percent classified as C, 14.5 percent as B, and 1.6 percent as A.

Margot Pottlitzer, a 30-year-old who had once been a student of journalism, came to Britain on a domestic permit and was working as a governess to “3 very unruly children in Gloucestershire” in 1939. She recalled that when she went before the tribunal she found the judge to be particularly benevolent and who said Margot was the type of person who could help with the war effort. The problem that Margot believed to exist was that the judge created his own subcategories of ‘C(1)’, which Margot assumed caused her to be interned and led her to claim this had happened to many others in her area.13 Looking at Margot’s tribunal record (which she would not have had access to at the time), it is possible to see she was actually classified as B by the judge, along with 8.2 percent of those who lived in her area (52 people including Margot). Such rationalisations were not uncommon when hiding the perceived stigma of being classified A or B.

Ludwig Spiro was living in Kingsbury at the outbreak of war, having come to Britain in 1936 and would have been seen by one of the North West London tribunals. He recalled going before a Mr Sandbach and there also being a representative from Bloomsbury House present, which is something that rarely happened at tribunals outside of London or the South East. Ludwig was asked if he was anti-Germany, to which he replied that he was anti-Nazi. Mr Sandbach classified Ludwig as B but told Ludwig this did not really mean anything to worry about and it was only a few days after the tribunal that Ludwig realised he had been “marked in an unfavourable light”.14 Only a minority of individuals in this region were classified as B, though it is likely that in Ludwig’s case this was because he had been in Britain for a few years which sometimes erroneously led judges or magistrates to believe such an individual was not actually a genuine refugee.

One final example in this small analysis is that of Margot Pogorzelski, later known as Margot Hodge, who came to Britain as a 19-year-old Jewish refugee and started work as a trainee nurse in Leeds. She was asked at her tribunal if she wanted to help Britain during the war to which she replied “Of course, but I think working in hospital is the best way of how I can help.”15 Despite this answer, she was classified B. The tribunal statistics show that Margot was not alone in this situation as the Leeds tribunal was one of the harshest of tribunals for classifications – of the 1,319 who came before the Leeds tribunal, 2.4 percent were classified A, 61.3 percent were classified B, and only 36.3 percent were classified C.

Conclusion

Geographical analysis of British government statistics relating to enemy alien tribunals has the ability to highlight many aspects of the refugee experience in Great Britain. Firstly, it has been possible to map the whereabouts of the adult refugee population, confirming certain expectations such as high concentrations in areas with Anglo-Jewish populations including North West London, Manchester and Leeds, as well as where refugees lived outside of these areas. Given that the majority of refugee charities were based in the Greater London area and that the majority of Germans and Austrians arrived in the UK through ports in Kent, Essex, and London, the concentrations of Germans and Austrians in these counties and those surrounding seems logical.

Secondly, the geographic distribution of adult refugees in Britain is a useful tool for use comparing how tribunals assessed individual cases and whether high concentrations of refugees in an area correlated with above average classifications. As has been demonstrated above, classifications varied considerably by geographic area – some areas with extremely high concentrations of refugees such as Richborough, Kent and North West London had sympathetic tribunals that classified almost 100 percent of Germans and Austrians as category C. Some areas had very low refugee populations and classified the majority of those who came before them as C such as Devon, Lincolnshire, Lancashire and Manchester. By contrast, other areas with relatively low refugee populations, such as Norfolk, Suffolk, East Scotland and Leicester, gave out extremely high classifications of A or B. There does appear to be a correlation of higher A and B classifications on the East Coast of Scotland and England. It is likely that, given that these areas became ‘protected areas’ because of their proximity to coastline that could be used in a German attack, that there was a greater distrust of foreigners in these areas. In areas where there were high levels of interaction between refugees and the local population, such as around Kitchener Camp in Kent, the tribunals appeared to be more favourable, but this did not necessarily extend elsewhere in the county.

Overall, this analysis suggests there may be additional factors at play to explain the diversity of classifications beyond the East Coast. By examining the guidance provided by the Home Office and also taking examples of tribunals as experienced by those who went before them, it is possible to get a fuller picture of what happened at this crucial time in the Second World War. Whilst prepared with the best of intentions, the guidance provided to the tribunals was open to variety of interpretations. The balance of power remained with the magistrate or judge in charge of the tribunal and any preconceived ideas they held relating to refugees is likely to have influenced them to be either extremely cautious or extremely sympathetic. Ultimately, more research is needed on individual tribunal judges to further investigate how political and other views may have influenced tribunal decisions.

- An ‘enemy alien’ is a foreign resident in a country with which his/her country is at war. ↩

- This post links to files held at The National Archives (UK) that EHRI-UK are working on adding to the Portal. This information is expected to be in the EHRI portal in late 2025 or early 2026. ↩

- See Panikos Panayi, “An Intolerant Act by an Intolerant Society: The Internment of Germans in Britain During the First World War,” in The Internment of Aliens in Twentieth Century Britain, ed. David Cesarani and Tony Kushner (London: Frank Cass and Company Ltd., 1993), 53–78. ↩

- TNA, HO 213/231 ‘Tribunals to review cases of enemy aliens: memorandum of guidance of appointees’, 1939. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- TNA, ‘Memorandum for the Guidance of Persons Appointed by the Secretary of State to Examine Cases of Germans and Austrians’, HO 213/231, 1939. ↩

- TNA, ‘HO 213/459 Summary of Cases,’ 1940-1942. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. All maps in this article have been created using MapChart.net ↩

- This was based on principles that had started as early as 1793 with successive Aliens Acts. See Rachel Pistol, Internment during the Second World War: A Comparative Study of Great Britain and the USA (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 9–13. ↩

- Some women and children were also included in this number. To find out more about Kitchener Camp, see Clare Ungerson, Four Thousand Lives: The Rescue of German Jewish Men to Britain, 1939 (Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2014). ↩

- Mark Lynton, Accidental Journey: A Cambridge Internee’s Memoir of World War II (Woodstock: Overlook, 1995), 14. ↩

- IWM, “Margot Pottlitzer Interview” (Held at the Imperial War Museum, 1978), 3816. ↩

- IWM, “Ludwig Spiro Interview” (Held at the Imperial War Museum, 1979), 4343. ↩

- Margot Hodge, “Memories and Personal Experiences of My Internment on the Isle of Man in 1940” (Held at the Manx National Archives, Douglas, Isle of Man, 1999), MS 10119. ↩