In the aftermath of the Holocaust, many Jews in Hungary returned to discover the destruction of their small communities. All Jews outside the capital city, Budapest, had been deported between April and July 1944. This came to approximately 440,000 people, many of whom were murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau. As the few survivors returned to the country, they found that their houses and property had been confiscated. While some of them worked to rebuild their lives in their former towns and villages, many moved to larger cities where there were more opportunities for aid and work, or they emigrated. Provincial Jewish communities, therefore, were particularly badly impacted by the Holocaust. Furthermore, their history has been largely ignored from the histories of the Holocaust in Hungary. Soviet era history removed the Jewish specificity of the Holocaust, replacing it with a political narrative of anti-Fascist struggle. It is only in the years since the fall of the Soviet Union that the Jewish history of the Holocaust has been explored in more depth.

In this blog post, I will showcase a new set of sources that help redress this imbalance, providing a piercing insight into local Jewish histories in Hungary. I will reveal how Hungarian Jewish community history books expand our knowledge on Hungarian Jewish history, give insight into Jewish and non-Jewish spaces and relations, and provide a springboard for further research. I will also reflect on their nature as sources. Mostly published in the last 30 years (but with some examples dating back to the 1960s), they provide new histories and information not seen before. Their authors are often amateur historians, local citizens, or museum staff, rooting them in the very communities that they seek to chronicle. These books are subjective sources, not professional histories, and need to be treated as such. As a result, I argue that we should consider them as a genre of their own, alongside but separate from the more well-known Yizkor memorial books.

Hungarian Jewish Community History Books

Hungarian Jewish community history books chronicle the local histories of specific areas. Each book is in itself a microhistory. The books form a genre of their own, each following a similar structure. First, they outline the foundation of the Jewish community and situate it within the Hungarian history of the area. They then describe the Jewish institutions and key figures, including rabbis, doctors, schools and synagogues. Often, they chart the history of the community through its chief rabbis, dividing time into the ‘era’ of each rabbi. Through this, they tell a local history of the community and how it was impacted by great events, including the Hungarian War of Independence in 1848–1849, the First World War, and the Holocaust. Many of the books then describe the post-war years, too, outlining both the reconstruction efforts and Soviet persecution. In addition to this history, the books also have a commemorative function, often listing the names of Holocaust victims from their area. In my research thus far, I have identified 25 of these books. They cover localities both inside Hungary’s borders today and in territories the country annexed during the war, including Transylvania and parts of southern Czechoslovakia. The map below visualizes these localities with Hungary’s wartime borders. The majority of the books, however, relate to areas that fall within Hungary’s current borders. This is perhaps unsurprising, given their production by Hungarian Jewish communities and museums today.

Mapping the Hungarian Jewish Community books was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin). See the full screen here.

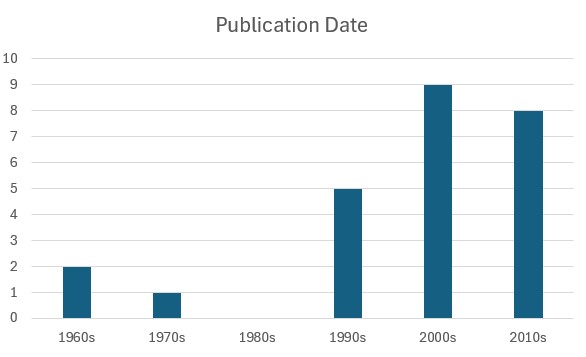

These books are similar to Yizkor books – Hebrew and Yiddish language memorial books that document the Jewish communities destroyed in the Holocaust. Indeed, several of them are listed as Yizkor books in the New York Public Libraries Digital Collections. Unlike Yizkor books, however, these are written in Hungarian and rooted in broader Hungarian history and culture, as well as the singular perspectives of their authors. Moreover, the majority of these books have been published in the last thirty years, as shown in the graph below. While the earlier books were mainly published in Israel, these later ones have been authored by local history museums, as well as Jewish communities and researchers in Hungary. Indeed, while the books do form a memorial to the Holocaust, that is not their sole – or even primary – function. Instead, they chart the longer-term history of the Jewish community as a part of Hungary, from its inception right up to the present. This reflects the deeply assimilated Hungarian Jewish tradition, which understood the Jewish community as a part of the Hungarian nation.

Publication of the Hungarian books has been sporadic. Some of them were written by dedicated amateur historians, such as Dr. Laszlo Szilagy-Windt, who has authored multiple local histories.1 Others have been published by the local Jewish community itself. This was the case for the Jewish Community of Komárom, who published their own history book in 2010, they claimed, as a way of reminding people of ‘what it was like when Hungarians, Slovaks, and Jews lived in peace and friendship’.2 Yet others have been published by local museums, including the municipal museum in Békés, southeastern Hungary, who launched their local Jewish history book in 2010.3 This diversity of authorship highlights one of the challenges of the books as sources. Unlike academic microhistories, these are often not professionally researched analyses. Instead, they are subjective accounts written by those connected to the events. Their perspectives have thus influenced their focus and the way they present their community’s history. Remembering this context is vital for understanding them as a genre, as it frames how we must treat them. Despite their unique characteristics, Hungarian Jewish community history books are not yet recognised as a genre. As such, there are no official collections of them, either by publishers or libraries and archives. In my own research, I have found many of these books in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, the British Library, the Hungarian National Library, the Library of the University of Chicago, and the libraries at Yad Vashem and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. At these institutions, the books are catalogued as Hungarian and Jewish local histories and integrated into wider collections. Instead of recognising them as a thematic collection of similar books, their categorisation has hidden their value to researchers.

An Example: Az Ujpesti Zsidóság Története (The History of Jews in Ujpest)

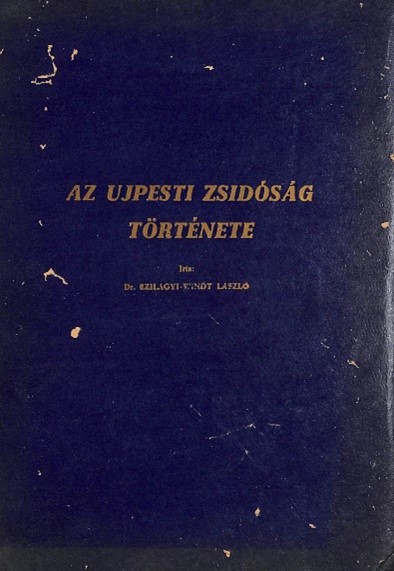

To show how the books contribute to our understanding of the past, I will now focus on one example, written about the Hungarian town of Ujpest. I have chosen this book because it is broadly representative of the genre and, therefore, offers a good case study for wider trends in the local Jewish history books. It is also widely accessible – original copies are available in 30 libraries worldwide, and an online copy is hosted on the website of the Yiddish Book Center. I’m grateful to Holocaust survivor Agnes Kaposi for providing me with her own copy while I researched this post.

Az Ujpesti Zsidóság Története [The History of Jews in Ujpest], is a Hungarian-language book written by Dr. Laszlo Szilagy-Windt and published in Tel Aviv in 1975.4 It charts the history of the Jews of Ujpest, now a district of an expanded Budapest. Until the 1950s, Ujpest was an independent town just outside the city’s borders before the 1950s. It had a Jewish population of approximately 13,000, accounting for roughly 14% of the local population.5 The vast majority (an estimated 12,000) were Neolog (liberal) Jews, while there was an Orthodox population of 460 and a small but growing Zionist community. During the Holocaust, most of its Jewish residents were deported to Auschwitz where they were murdered.

Little is known about the book’s author, Dr. Laszlo Szilagy-Windt. He was born in 1902 in Nagykálló, eastern Hungary and trained to be a lawyer. In 1940, he was conscripted into the Hungarian forced labour battalions known as the Munkaszolgálat and was deployed to several locations within Hungary before being deported to Mauthausen in November 1944.6 After liberation, he lived in Ujpest. In 1957 he emigrated to Israel, where he died in 1982. His interest in Ujpest appears, therefore, to be that of a local resident after the war.

Az Ujpesti Zsidóság Története follows the typical structure of community history books: from the establishment of the Jewish community there in 1835, through the eras of several chief rabbis, to the reconstruction of the community in Soviet Hungary, and with a long list of Holocaust victims. Through this, it contributes a new aspect to our understanding of Ujpest’s Jewish history. It fills gaps left by under-researched aspects of Hungarian Jewish history, provides insight into Jewish and non-Jewish spaces, and opens new opportunities for further research.

Expanding Hungarian Jewish History

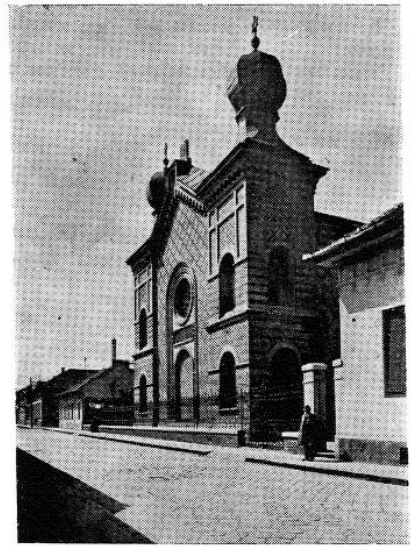

By chronicling the history of the Jewish community in Ujpest, the book gives an overview of the community as a whole. As a result, it details the different Jewish groups that comprised the community, revealing a diversity in political and denominational affiliation. The book contains photographs of both the Neolog (Hungarian liberal) and Orthodox synagogues and describes the different Neolog, Orthodox, and Zionist organisations that operated there.

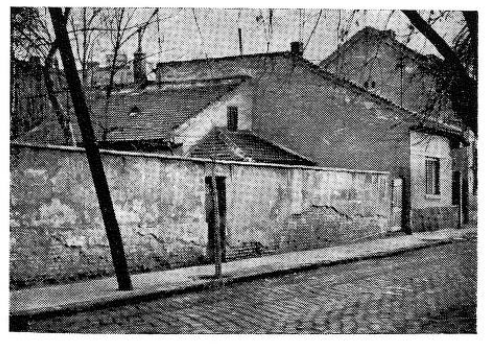

The author’s attention to the Orthodox community is particularly noteworthy, as there was an especially small Orthodox community in Ujpest (460 members, compared to the 12,000 Neolog members in April 1944). Nonetheless, Az Ujpesti Zsidóság Története charts how the Orthodox community was established in 1886 as a breakaway branch of the existing community, appointing their own chief rabbi in 1910.7 They built their own synagogue and mikve (ritual bath) and joined a national Orthodox organisation in 1929.8 After the war, however, only 80 members of the community returned and many ‘could not handle living there anymore’, choosing to emigrate.9 As a result, when the book was published in 1975, there was only one orthodox family living in Ujpest. The synagogue had been turned into the city’s nursery. These details give important insight into the history of the Orthodox community, both in Ujpest and, more broadly, in Hungary. As a minority within a minority, Orthodox Jews are often poorly represented in archives. By providing an outline of Orthodox community institutions and spaces, the local history books thus form a valuable source of knowledge about this under-represented area.

Jewish and non-Jewish Spaces

While the books focus on the local Jewish community, it is important to note that they are rooted in the Hungarian context, too. As a result, they give an insight into Jewish and non-Jewish spaces and relations on a micro level. The Ujpest book, for example, describes how ‘the men who could carry arms enlisted’ into the Hungarian army during the First World War while their families took part in ‘social and humanitarian’ work with their non-Jewish neighbours.10 When a Jewish school was re-established by the community after the Second World War, the Hungarian Polgármester (Mayor), Döbrenti Karolyné, personally visited one of the classes. The activities of the Jewish community were, therefore, often connected to the wider Hungarian community and institutions.

These were not, however, straightforward and unproblematic. The Ujpest book also tells of how the Jewish cemetery was vandalised in 1940.11 Moreover, only one year after the Polgármester visited the Jewish school in 1947, it was ordered to close as the Soviet government exerted its control over education.12 By reporting all of these, seemingly minor, details, the book sheds light on the complex balance of assimilation and antisemitism that so characterised Jewish life in Hungary in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

It also charts the development of Zionism in Ujpest, from a minor and largely irrelevant group before the Second World War to a major part of wartime resistance and rescue and post-war reconstruction. The book outlines how in the 1920s, one family was the ‘center’ of the Zionist movement in Ujpest, holding discussion groups in their own home.13 It was only in 1933 that Ujpest formed a more official Zionist group and joined the Hungarian Zionist Association. During the war, however, it was the “youth groups, with the direction of the Karpathian Chalutz (Zionist youth) [who] took part in the building of secret bunkers, the escape to Romania, and in rescue actions dressed in Nyilas (Arrow Cross) uniforms”.14 After the war, Zionist activity restarted ‘in great measure’, with a large committee organising social and cultural activities.

By recording this history, the book reveals how a local community took part in larger denominational and political trends in Hungary. It shows how they experienced this in their own homes at first, only connecting with a national organisation later. It also links the development of the community’s diversity to their response to the Holocaust, showing how different groups responded in their own ways. The book therefore draws attention to the interaction between the community on a micro scale and the macro ideas and events that it encountered.

New Opportunities for Research

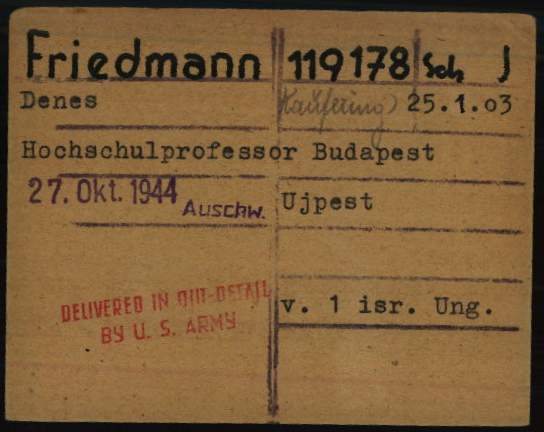

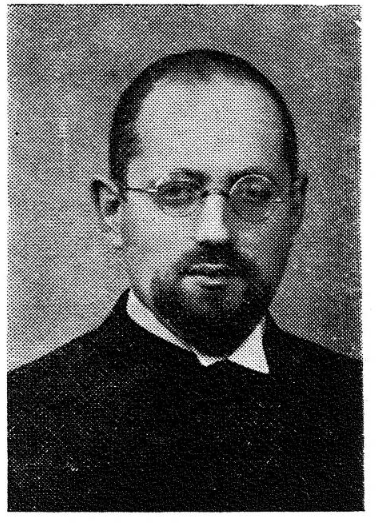

When charting this history, the book often lists the names and biographical details of the Jewish community figures who were involved. Indeed, the wealth of individual biographical detail is a striking aspect of the books in general. This makes further research possible and opens up opportunities for new discoveries. The Ujpest book, for example, describes the life and death of Dr Dénes Friedman (1903-1945), the chief rabbi from 1927 to 1944. It explains how the Ujpest Jewish community was deported to Auschwitz where, after his son was killed, the rabbi “followed his son to death”.15 This gives us details about a victim of the Holocaust, acting as a memorial to his life. It also provides a starting point for further research. In fact, searching for Dénes Friedman in other archives reveals more complexity than the book initially makes out.

According to a Yad Vashem page of testimony filled out in 1998, Dénes committed suicide in Auschwitz after his son was killed. 16 This corroborates the narrative in the Ujpest book, both on place and cause. Documents from the Arolsen Archives, however, suggest a different history. His personal card file from the camp system shows how, after he was deported to Auschwitz in July 1944, he was transferred to Dachau on 29th October 1944, from where he was sent to the Kaufering subcamp. 17 The Dachau entry register also records his transfer, and several survivors recall seeing him in Kaufering in their interviews with the USC Shoah Foundation (Visual History Archive). 18 Here, the trail runs cold, with no further documents about him. It is likely, therefore, that he died in Kaufering rather than Auschwitz.

This example reveals how the community books can provide a starting point for more detailed research. By recording Dénes’s name and year of birth, the book drew attention to a historical figure from the community and provided the necessary information to find him in archival holdings across the world. The results, however, reveal a lack of nuance in the book, which presents an incomplete picture of his fate. This does not invalidate the book itself, which provided otherwise accurate information on Jewish life and the deportations. Instead, it shows its limitations. Especially for some of the earlier books which are less transparent about their sources, they must be read as primary sources themselves, giving detailed insight into the local history, but not always completely accurate in their memory.

Community History Books and Writing History

How, therefore, should we approach these books? As this post has shown, they have a distinct structure and can make important contributions to our understanding of the past. Because of their local focus and encyclopaedic style, they provide information on understudied elements of history. They give us a local perspective on big issues, showing how localities interacted with and responded to larger trends. They also give us a platform from which to embark on further research, providing basic details of people and organisations that were active in each place. For researchers on the history of Jews in Hungary, therefore, these books can form an important reference point for near comprehensive coverage of many local communities across the country. Treating the books as a genre of their own helps us understand their contribution and their limits. They need not be labelled as merely a memorial to the dead, nor expected to make broad arguments on the major historiographical debates. Instead, they contribute to debates by showing how forgotten regions lived, felt, and acted in history. They provide narratives that would otherwise be lost to the destruction of the Holocaust, protecting provincial histories not recorded elsewhere. Yet, they also show how some of these narratives are alive; not ending with destruction but stretching forward to today, placing the Holocaust into the context of an ongoing Hungarian Jewish local history. We need to understand these books in all of this complexity. While they have often been integrated into collections on Hungarian history, drawing them out as a genre of their own recognises their specificities and their contribution. As we seek to uncover new histories from the past, these books are where we should start.

- Laszlo Szilagy-Windt, Az Ujpesti Zsidóság Története (The History of Jews in Ujpest), (Tel Aviv, 1975); László Szilágyi-Windt, A kállói Cádik: A nagykállói zsidóság tortenete (The Cádik of Kálló: The History of the Jews of Nagykálló), (Haifa: a szerző saját kiadása, 1960?). ↩

- László Varga, Velünk éltek: a nagymegyeri zsidóság története (They Lived With Us: The History of the Jews of Nagymegyer) (Komárno : Komáromi Zsidó Hitközség, 2010). ↩

- Ildikó Nagy, A békési zsidóság története (The History of the Jews of Békés), (Békés: Jantyik Mátyás Múzeum, 2010). ↩

- Laszlo Szilagy-Windt, Az Ujpesti Zsidóság Története (The History of Jews in Ujpest), (Tel Aviv, 1975). ↩

- Guy Miron and Shlomit Shulhani (eds.), The Yad Vashem Encyclopedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2009), pp. 858-9. ↩

- Tracing and documentation case no. 934.728 for SZILAGYI, LADISLAUS born 09.08.1902, 6.3.3.2/934.728, ITS Digital Archive, Wiener Library, London. ↩

- Szilagy-Windt, Az Ujpesti Zsidóság Története, pp. 26-7. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 30-1. ↩

- Ibid., p. 33. ↩

- Ibid., p. 41. ↩

- Ibid., p. 50. ↩

- Ibid., p. 235. ↩

- Ibid., p. 237. ↩

- Ibid., p. 239. ↩

- Ibid., p. 49. ↩

- Page of Testimony for Dénes Friedmann, Yad Vashem, Item ID: 567761. ↩

- Dénes Friedmann Personal File from Concentration Camp Dachau, 1.1.6.2/10056534, ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives. ↩

- Dachau Entry Register, 1.1.6.1/130432575, ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives; Sándor Somogyi Interview, USC Shoah Foundation, Visual History Archive (henceforth USC SF VHA)/51232, seg. 51; László Balázs Interview, USC SF VHA/50220, seg. 92. ↩

TZIPPORAH

THIS SEEMS VERY IMPORTANT. I WOULD APPRECIATE THE AUTHOR GETTING IN TOUCH WITH ME, THANK YOU.