“After Ilonka and I were shown to an apartment in a building, we stayed inside with one group of children, huddling because of the cold. […] I was aware of the scary situation we were in, but unlike Ilonka, I did not feel scared. In fact, I did not feel much of anything at all, except cold and hungry.”1

This was how Kitty Salsberg remembered the Pest ghetto in her memoirs – and, in fact, this was also a general experience of those Jews who were forced to live in this ghetto, established in the heart of Hungary’s capital.

The Pest ghetto was the last ghetto to be set up during the time of the Second World War: it was sealed on 10 December 1944, when the Red Army was already advancing on the capital. This was not the only unique feature of this ghetto, though: like many other ghettos in Hungary, it existed only for a bit more than a month – it ceased to exist not because its inhabitants were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau but because the Soviet army liberated them on 17–18 January 1945. Thus, despite the devastating losses, most of those Hungarian Jews who were forced to live in the ghetto survived the Holocaust.

While some basic information about the Pest ghetto is well-known among both researchers and the general public, interestingly, little has been written about its microhistory, despite the abundance of sources and recollections which are available in large numbers due to the high number of survivors. The most important primary collection is the so-called “ghetto documents”: sources produced by the Jewish Council which concern the organization of the ghetto’s administration and its everyday functioning. Additionally, Jenő Lévai2 collected and published selected sources with his own commentary in A pesti gettó története (The History of the Pest ghetto)3 – this volume completes the aforementioned, sometimes fragmentary documents with important details. Memoirs of ghetto survivors have been published both in Hungary and abroad. I will mention only two examples: the Azrieli Foundation’s series contains several such recollections and memoirs, and in a recently published collection entitled A Vészkorszak árvái (Orphans of the Shoah),4 the editors included recollections by survivors who were children when taken to the ghetto. In this post, I explore the history of the ghetto area and the connections between microhistorical events and the ghetto’s topography based first and foremost on the so-called “ghetto documents”: sources produced by the Jewish Council. It is my hope that with these topics, I can contribute to a more thorough understanding of the Pest ghetto’s existence. The research done on the Pest ghetto is part of the AR project If these streets.

Mapping the addresses of the Pest Ghetto was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin). See full the screen here.

History and historicity of the “Jewish district”

Pest’s traditional “Jewish district” is part of today’s 7th district called Erzsébetváros. The first Jews arrived here at the end of the 18th century from the Óbuda community when the city of Pest granted them permission to settle. However, they were not allowed to live within the city walls. Therefore, the first settlers looked for a place east of the border and established their own market at a square which is considered Budapest’s center today: Deák Ferenc Square. Appropriately, the square was called the “Jewish market” at the time and tanners, merchants, and weavers worked there.5

Later on, the center of Jewish life moved a bit more to the east, to the so-called Orczy house, which was named after Barons István and József Orczy, who purchased the two buildings and united them. The resulting monumental, two-story baroque building, which stood in the place of today’s Madách houses at Károly Boulevard, was famous for several reasons: first of all, it was built in the place of the König von Engelland Inn, popular among travelling merchants, which gave name to Király (King’s) Street, the center of Budapest’s party zone today. Second, the Orczy house was Pest’s second largest building with apartments, stores, cellars, and shops. It functioned as a city within a city, especially for the Jewish inhabitants who had their own baths,6 synagogues, school, slaughterhouse, and shops in it. Soon, the building became an anchor for newly arriving Jewish families – they could be sure to find a functioning community and all the necessary facilities in it.7

The Orczy house was demolished in 1936 – by that time, Király Street became central to local Jewish life. In the mid-19th century, it counted as a posh street with dense traffic and buildings designed by famous architects. Jewish religious infrastructure thrived in this environment with synagogues, prayer rooms, Talmud Torah, and mikveh. Jewish economic life also concentrated in and around Király Street: bargaining and sales took place in the numerous coffee houses (first and foremost in the Orczy Café); shops, workshops, and small factories lined the street. 8

The mid-19th century saw a boom in Jewish life, especially after the Emancipation Act of 1867. In 1859, the construction of the Dohány Street synagogue, Europe’s largest synagogue, was completed. This monumental, spectacular building is the proud symbol of assimilated Jewish–Hungarian identity, as it resembles a Christian basilica with the traditional embellishments and features of Jewish architecture. The followers of the community’s modern, assimilationist branch (Neológ) used this synagogue, while the Orthodox community also built their own synagogue, mikveh and school in Kazinczy Street in 1913. Finally, a smaller group of conservatives remained in the Orczy house, but soon they bought the plot of a former prayer house in Rumbach Sebestyén Street. This was the place where, based on Otto Wagner’s plans, the Rumbach synagogue was built in 1872. It became the religious center of the so-called Status Quo Ante congregation. These three belong to the famous “synagogue triangle” of the Jewish district, with each of the three major denominations represented by the three buildings.

Other focal points of Jewish life in the district were Síp Street 12, headquarters of the Neolog Pest Israelite Congregation and center of Jewish religious and communal administration, Klauzál Square, where the market operated (both kosher and non-kosher), Wesselényi Street 7, where, in the Goldmark hall, cultural events were held and a Jewish theater operated during the Shoah. During its first 150 years, the district developed into a new quarter of Pest. This historical district not only represented Jewish life in the capital, but it was also home to a variety of unique buildings of historical importance, some of which provided home to the institutions of the Jewish congregations. Even though initially it represented the exclusion of the Jewish population as they were not allowed to move within the city walls nor use the city’s existing infrastructure, they built out their own – and soon they became crucial for Pest’s economic and cultural life.

“Dispersed ghetto” – The yellow star houses

In 1944, after the German occupation of Hungary, regent Miklós Horthy appointed the German-friendly Döme Sztójay prime minister. This was followed by one of the swiftest “dejudaization” operations of the Holocaust: the authorities set up ghettos from mid-April, while during the mass deportation between 15 May and 8 July, entire rural Hungary was emptied, and 437.402 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and Strasshof.

At the same time, ghettoization plans for the Budapest Jews were also formulated. According to the initial plan, Jews would have had to move to the territory between Rákóczi Street and Podmaniczky Street, and their emptied homes would have been given to bomb victims. This was complemented by a number of other small territories – three in Buda and four in Pest. As Tim Cole pointed out, this way, not only would have Jews and non-Jews been separated spatially but the main streets and squares of the capital would have remained “Judenfrei”.9 However, the execution of this plan would have been accompanied by moving too many non-Jews from the area. Therefore, the plan was discarded.10

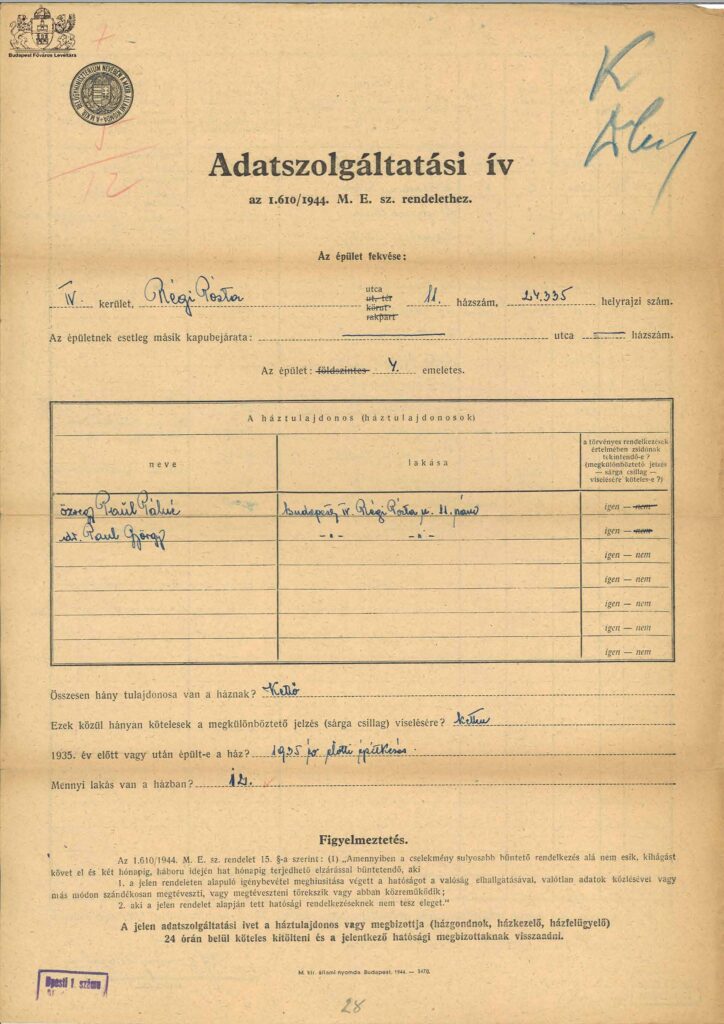

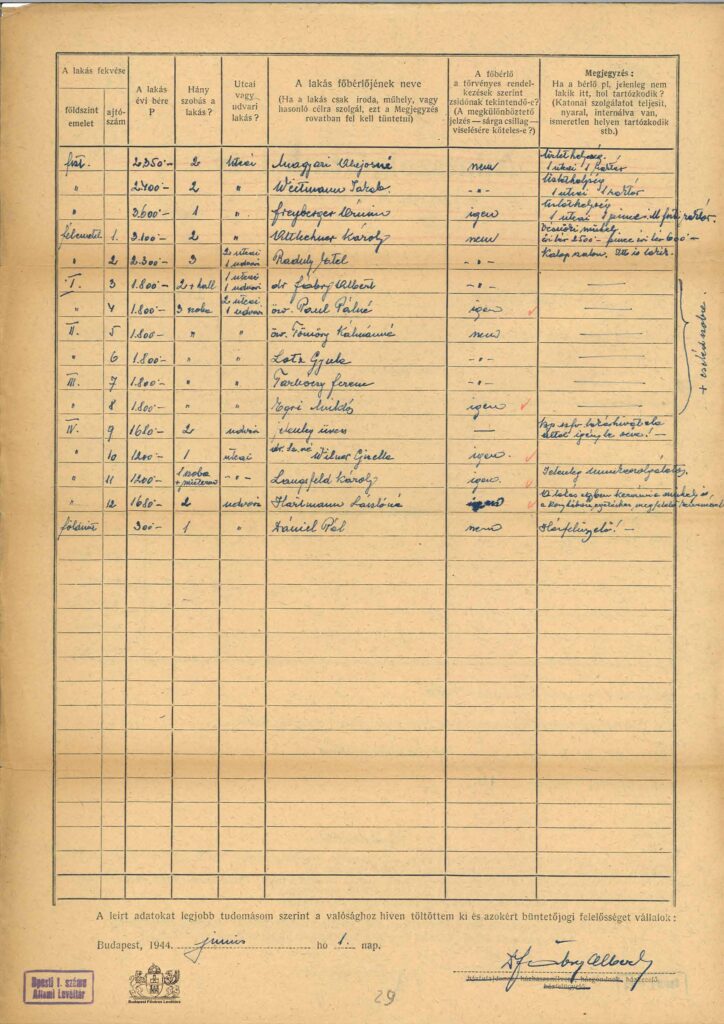

At the beginning of May 1944, the secretary of the state in charge of the “Jewish question”, László Endre, ordered the listing of apartments inhabited by Jews – based on this list, the plan of the so-called yellow star houses was formulated. Instead of a closed-off area, Endre envisioned houses marked with yellow stars dispersed throughout Budapest. This served several goals: first, bombed-out non-Jews could be placed in the emptied Jewish apartments. Second, Jews were concentrated and segregated, which would have eased their planned deportation. Third, the Allied bombing could have been prevented by keeping the Jewish population of Budapest as “hostages”, thus the yellow star houses would have served as a shield.11 The designation of the yellow star houses depended on a variety of factors: the building’s conditions, its location, the number of “Jewish apartments” in it, the person of the building owner, the extent of rental fees and so forth. This provided an opportunity for the officials to reorganize the housing of the majority of Budapest’s population, to place non-Jews in better situated houses with lower fees, while forcing the Jews into unfavorable living conditions. The yellow star houses can also be viewed as a compromise between strategical considerations and the interests of the non-Jewish population, as in many cases the decisive factor whether a building was designated, depended on its majority occupation.12

Initially, the authorities designated nearly 2.700 yellow star houses. The decree about relocations was published on 16 June, and it was complemented by individual lists of yellow star houses in each district. The buildings were to be marked with a 30 cm-large yellow star on the gate. Jews had to find their new apartments and move by 21 June, while non-Jews had a longer deadline for moving (30 June) and were also offered compensation. Each Jewish family was entitled to one room – except if the family consisted of more than five members or the room was smaller than 25 m2.13 The process was hindered by the hundreds of petitions sent to the City Hall, mostly by non-Jews who asked for their houses to be exempted.14 As a result, the authorities reduced the number of designated houses to approximately 2.000, which list was published on 22 June together, and they extended the deadline for Jews to move to 24 June.

We can only imagine the mass scenes of the relocation: most of the 200.000 Jews living in 10.000 buildings dispersed all around Budapest, had to move into the designated 2.000;15 moreover, some had to move twice because in the list of 22 June, the designation of their new apartment was withdrawn. As Ernő Munkácsi, a member of the Jewish Council, described, “24 June was a Saturday. Budapest was the scene of a spectacle which has not been seen for centuries. The children of Israel carried their belongings and the most necessary furniture in carriages, handcarts, wheelbarrows and – those who did not have anything else – on their backs into the »designated« houses.”16

One day after the second deadline, various new restrictions were imposed on the Jews: a curfew which meant that they could leave their homes only between 2 and 5 pm (later this was modified to 11–5), and they were not allowed to visit various institutions such as baths, hotels, restaurants, theaters, unless they were specifically designated.17

While originally the yellow star houses were intended as a temporary accommodation before the deportation of the Budapest Jews, in the end that plan was cancelled and the Jewish population remained in these apartments until late autumn.

The Pest ghetto – Establishment

In the autumn of 1944, after a relatively peaceful period for the inhabitants of the yellow star houses, the anti-Semitic Arrow Cross party came to power. Determined to continue the war until the end and solve the “Jewish question” their own way, party leader Ferenc Szálasi’s final aim was to deport all Jews from the territory of Hungary after the war. However, he could not ignore the international pressure which had also inspired Regent Horthy to stop the mass deportations. Therefore, instead of handing over the Jewish population of Budapest to the Germans, he decided to create various groups based on exemptions, as a result of which a number of “protected houses” were assigned in the 13th district, where those Jews could move who had protective passes from neutral countries. Additionally, through general mobilization, tens of thousands of Jewish men and women aged 16–60 were taken to forced labor.18

On 18 November, the government informed the Jewish Council that they would set up a ghetto in the 7th district. How unequal partner the Jewish Council was during the negotiations can be seen from their memorandum sent to the lord mayor the next day: “Deputy commander [János Solymossy]19 invited the representative of the Temporary Commission of the Alliance of Hungarian Jews to participate at the meeting deciding on the fate of the Jews. Unfortunately, our delegate was excluded from the meeting and he [Solymossy] informed him only after the conference that those Jews who have not yet been deported, […] will be placed in a ghetto.”20 This humiliating treatment was combined with ignorance toward the Jewish Council’s repeated pleas and requests – even though they emphasized that locking up the entire Jewish community of Budapest in such a small space without any infrastructure would be equivalent to their mass destruction, and that they, as a representative body, could not undertake participation in such a project.

Hungarian Jewish Archives, MILEV XXXIII-5-c.

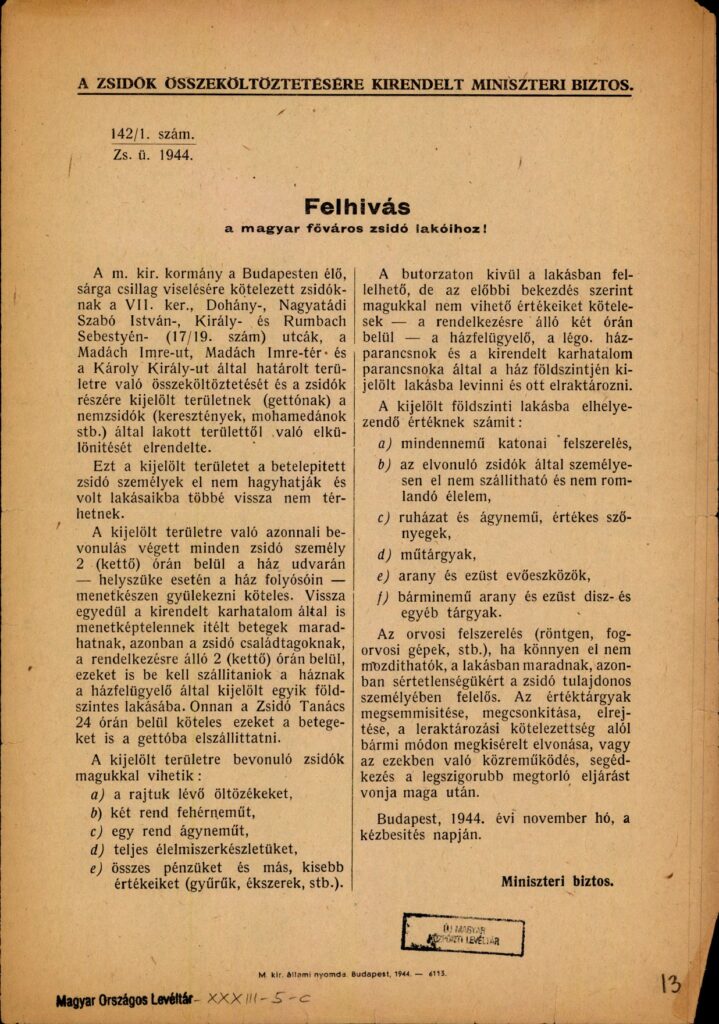

The Arrow Cross government published the ghetto decree on 29 November. The decree issued next contained the following regulations: “Every Jewish individual must gather at the courtyard of the house within two hours. Only those can stay who are deemed unfit to march by the police; but Jewish family members must take them into a ground floor apartment assigned by the concierge within the two hours at their disposal. From there, the Jewish Council is obliged to transport these ill people to the ghetto within 24 hours. The Jews may take with themselves: their clothing, two sets of underwear, one set of bedding, all their money and other smaller valuables. Apart from their furniture, […] they must place the following valuables in the assigned ground floor apartment: all military equipment, whatever food, clothing and bedding they cannot take, valuable carpets, artefacts, gold and silver cutlery, other gold and silver items.”21

This decree reflects the merciless attitude toward the Jewish population: they received merely two hours to pack up their valuables which must not have been sufficient in bigger tenement houses where people most probably queued for a long time until they could place all their belongings in the designated apartments. The decree also does not mention any planned facilities for the ill – indeed, the Jewish Council had to organize the health care network in the ghetto. Additionally, the Szálasi government had already introduced decree no. 3840/1944. ME. on 3 November which declared that all Jewish property “is transferred to the state as national property,”22 but even earlier decrees had decimated the wealth of the Jews. Even so, the Arrow Cross expected to gather artefacts, and gold and silver items in the course of the ghettoization.

Even though there were 162 yellow star houses in the planned territory of the ghetto, a substantial non-Jewish population – approximately 12.000 people – also lived there in the “mixed houses” and the 133 non-yellow star houses. These people would have to leave the ghetto, and more than 60.000 Jews would move in instead.23 According to a 24 November memo, Solymossy declared that the reason why Jews were allowed to take only what they could bring in their hands was to free at least 6000 Jewish apartments for these non-Jews. “We reported that this amount of empty Jewish apartments is already at disposal, to which he said that he did not know where these apartments were located. We offered to write a list within 24 hours to which he stated that the [Arrow Cross] party insists on implementing the announced [decree].”24 This note makes it clear that emptying the apartments was only a pretext for the ghettoization which rather served as a means for “solving the Jewish question”.

In contrast, the non-Jews who moved out, could occupy former Jewish apartments without much administrative effort. Moreover, they could place their “valuable, or particularly beloved furniture” in assigned apartments outside the territory of the ghetto.25 As a result, while the Jews could not take basically any furnishing items, they often arrived in emptied apartments. According to the Jewish Council’s statistics, there were 2.393 Jewish apartments in the ghetto area, with 4.725 rooms, and 3.320 non-Jewish apartments with 5.159 rooms.26 For the planned 63.000 Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto, this meant more than six people per room. The massive population resettlement took place from the end of November: Jews had to start moving in after the ghetto decree was published, at the speed of approximately 10–15.000 people per day. However, at first, they could only stay at the Jewish apartments of the yellow star houses, as the non-Jews moved out only between 2 and 7 December. This also meant that the yellow star houses were excessively overcrowded in the first days; moreover, during those six days while the non-Jews were moving, Jews were allowed to leave their apartments only between 9 and 11 AM. Finally, on 10 December, the ghetto was sealed – from this time, no one was allowed to leave.

The Pest ghetto – Topography and life in the ghetto

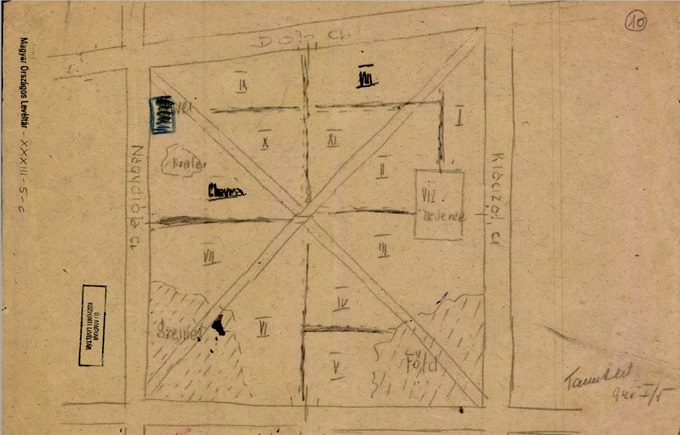

The ghetto territory, which lay at the heart of the Jewish district, incorporated ten streets: Dob, Wesselényi, Rumbach Sebestyén, Síp, Kazinczy, Kis diófa, Nagy diófa, Nyár, Klauzál, and Akácfa streets, as well as two buildings from Csányi Street. As Tim Cole observed, the ghetto boundaries were set in a way that the houses facing the streets bordering the ghetto were restricted for the Jews – therefore, the ghetto became “an island looking in on itself.”27 The 0.3 km2 territory was surrounded by a high fence for whose construction the Jewish Council had to pay.28 The short segment of the ghetto wall which still exists today under Király Street 15 shows that the “Jewish” and “non-Jewish” apartments on the ghetto border stood right next to each other, therefore, despite the wall between them, the non-Jewish tenants could see and hear what was happening on the other side.29 The ghetto initially had four gates: the main gates were next to the Dohány Street synagogue and at the intersection of Wesselényi and Nagyatádi (today Kertész) streets. Two additional gates were at the ends of Kis diófa and Nagy diófa streets. On 10 January the latter were locked up due to the constant Arrow Cross raids.

Arriving Jews had to gather at Klauzál Square, the heart of the ghetto area. Here, at the main market hall, they had to hand over all their valuable property to the authorities, and they were assigned apartments. Until 10 December people could enter and leave the ghetto, however, on that day the gates were closed, and henceforth leaving was allowed only with special permissions. The Arrow Cross and the authorities often dumped bigger groups of people in the ghetto: for instance, in mid-December, several thousand children arrived who had been taken care of in orphanages under the Red Cross’ protection.30 Therefore, the initial number of inhabitants quickly grew from 40–45.000 to close to 70.000. Close to 300 buildings stood in the ghetto area, out of which the Jews could use only 240 with several buildings being locked up by the authorities for various reasons.31

The enormous task of administrating this “city-within-a-city” fell entirely upon the Jewish Council. They had to take care of alimentation, housing, health care, burials, public utilities, and additionally, the mental health of the ghetto dwellers: cultural activities, education, and so forth. In order to keep a basic order, most of these tasks were distributed among smaller units: the ghetto territory was divided into ten districts with one headquarters in each, where the district leader and his two deputies worked. They had to take care of food distribution, administration, keeping the regulations of the Jewish Council, etc.32 Originally, converted Jews – who were not obliged to put out the yellow star – were to be placed in the tenth district (Csányi, Dob, Nagyatádi streets),33 however, according to Miksa Domonkos, “no one took this advantage and the ghetto inhabitants mingled without any distinction.”34

Besides the districts, every building had an appointed commander who had to take care of the building’s order, cleanliness, guarding during the night, and care for the elderly and children. While these tasks seem relatively simple, among the ghetto circumstances, decision-making processes were often complicated. This is reflected in a decree sent by Miksa Domonkos, commander of the ghetto police, at the beginning of January 1945. Domonkos ordered all house commanders to keep the gates open during bombing or other dangers: “it is a fraternal obligation and an air raid regulation that individuals looking for safety could get through the gates in the case of danger,” he warned them.35 This decree implies that it occurred more than once that certain houses were locked up and people died or were injured in the streets while lacking shelter.

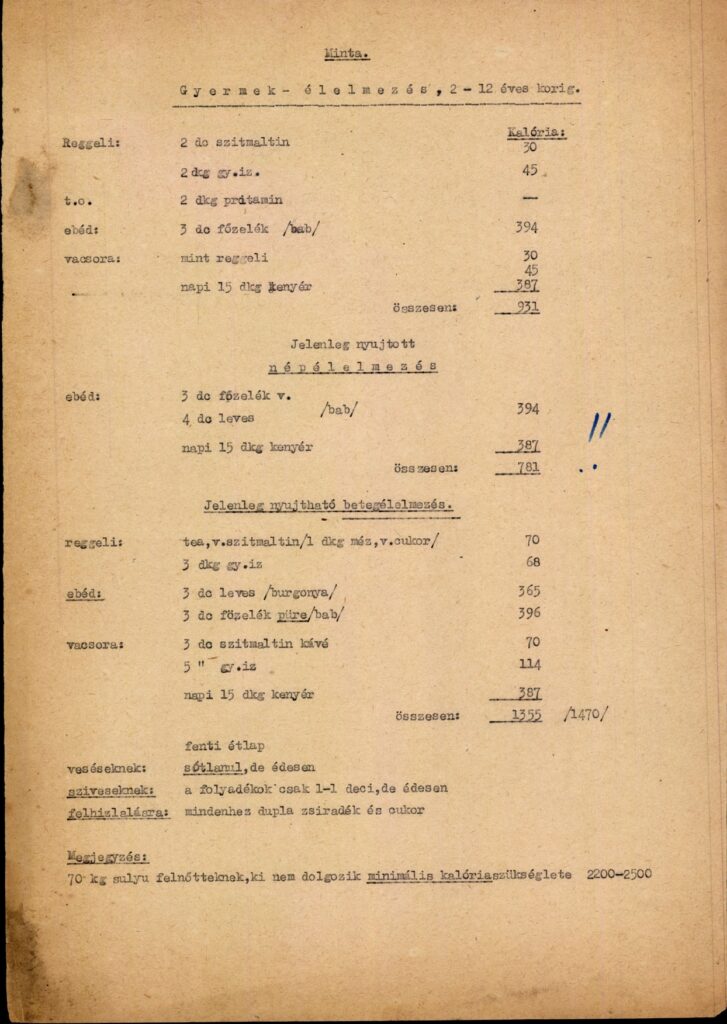

On the top: 931 kcal for children; 781 kcal for adults – marked with two exclamation marks, then 1355 kcal for the sick. On the bottom of the page: “Note: a 70-kg adult who does not work requires 2200-2500 calories minimum”. Hungarian Jewish Archives, MILEV XXXIII-5-c

Each district also had a ghetto police headquarter where Jewish policemen worked. According to the sources, the most important tasks of these policemen were checking the identities and papers of those who wanted to leave the ghetto territory, and control and prevent theft and plunder: in their dire need, the ghetto dwellers often broke into locked-up shops and took whatever they found there.36 Among the ghetto documents, at least three letters report on the death of ghetto policemen: in one case, the policemen were shot by the Germans, while another one died in a bomb attack.37 From the former case – which happened near the Dohány Street synagogue – we may surmise that the environment of the gates were especially dangerous places within the ghetto as the enemy – the Germans and the Arrow Cross – could enter through them anytime.

Since the government did not allow individual cooking,38 the Jewish Council had to take care of alimentation centrally. There were a number of soup kitchens in the ghetto, mostly organized in former restaurants, such as the Stern Kitchen (Rumbach Street 10). Ingredients were provided by the Red Cross, the city government, and the Jewish Council itself.39 Still, the daily intake was merely 931 kcal for children, 781 kcal for adults and 1355 kcal for the ill.40 The food was distributed among districts, and within the districts, among individual houses – another task for house commanders. In the ghetto, obtaining drinking water was also extremely problematic. By the end of the war, most public utilities were destroyed,41 so the ghetto inhabitants had to get water from the wells of ritual baths, such as the one at Kazinczy Street 16. The last working well was under Rumbach Street 10, in the Stern kitchen.42

The ghetto had the same curfew which was in effect in the whole city: for civilians it was prohibited to go out after 5 PM, under the penalty of death. However, certain people – couriers, representatives of the Jewish Council, critically ill, etc. could obtain permits for staying outside. These papers were issued by the Arrow Cross authorities, the state police or the Jewish Council.43 However, as most survivor testimonies emphasize, the people were too afraid to go out and the bulk of the ghetto dwellers spent the entire time locked up in their apartments.

The ill and the wounded were treated in the central hospitals of Wesselényi Street 44 and Bethlen Square 2. Since both were outside the ghetto boundaries, they were more exposed to Arrow Cross attacks and it became increasingly more difficult for the ghetto dwellers to go out if they had to be treated. Within the ghetto, there were several other hospitals and health care facilities, especially around Klauzál Square – some set up by the Swedish Embassy, others by the Jewish Council or the Red Cross, however, most of them struggled with the lack of public utilities, proper beds, medicine and hygienic circumstances.44

In general, the ghetto as a whole suffered from the lack of hygiene: since the garbage was not taken from its territory, soon heaps of rubbish covered the streets, the smell was unbearable.45 The same was true for the dead bodies: initially, the Jewish Council had permission to transfer them to the Jewish cemeteries, however, on 3 January 1945, this possibility ceased. Since approximately 80–100 people died per day due to starvation, diseases, and the Arrow Cross raids, various places were assigned for collecting them: Kazinczy Street 40 (ritual bath), the courtyard of the Dohány synagogue, and Klauzál Square. According to the decree of the responsible ghetto authorities, house commanders were obliged to send a list of the dead to the district leadership and take care of the burials. For this purpose, the territory of the Klauzál Square was divided into ten sections – one for each ghetto district. “The graves must be 2 m deep and without intervals. In each grave, three corpses must be placed with a 10 cm layer of soil dividing them.”46 Despite all efforts, though, the number of dead bodies increased and in the winter weather, under the siege, it was close to impossible to dig up the frozen soil of the square – therefore, piles of bodies soon appeared in the courtyards and gardens of the buildings, in shops, hospitals, and of course at Klauzál Square. When the ghetto was liberated, 3.000 unburied dead bodies were found scattered in its territory.

The Red Army liberated the Pest ghetto on 17–18 January 1945.

This blog post describes only a handful of topics connected to the Pest ghetto’s existence and functioning, however, there are many more issues and sources which could be included in a more comprehensive analysis. Since as of January 2024, this research has been nearly completed, my plan is to write such a paper in the future.

- Kitty Salsberg, Ellen Foster, Never far apart (Toronto: Azrieli, 2015), 38. ↩

- Jenő Lévai (1892–1983) writer, journalist. He survived the Holocaust in the so-called international ghetto of Budapest. ↩

- Jenő Lévai, A pesti gettó története (Budapest: Budapest VII. kerület önkormányzata, 2014). ↩

- Viktória Bányai, Kinga Frojimovics, Eszter Gombocz (eds.), A Vészkorszak árvái. A magyarországi zsidó árvaházak és gyermekotthonok emlékezete (Orphans of the Shoah. The memory of Jewish orphanages and children’s homes in Hungary), (Budapest: NÜB, 2020). ↩

- Kinga Frojimovics, Géza Komoróczy, Viktória Pusztai, Andrea Strbik, A zsidó Budapest (The Jewish Budapest), (Budapest: MTA Judaisztikai Kutatócsoport, 1995), 100. ↩

- On the topic whether this was a bath or a mikveh, see: Gábor Dombi, Rituális fürdők nyomában a régi Pesten (Tracing ritual baths in old Pest). Egység vol. XXXI, no. 139–140 (2021): 17–18. ↩

- Frojimovics, Komoróczy, Pusztai, Strbik, A zsidó Budapest, 101–107. ↩

- Ibid. 118–121. ↩

- Tim Cole, Holocaust City – The Making of a Jewish Ghetto (London, New York: Routledge, 2003), 85–90. ↩

- Randolph L. Braham, A népirtás politikája – A Holocaust Magyarországon (The Politics of Genocide – The Holocaust in Hungary) II, (Budapest: Belvárosi Könyvkiadó, 1997), 810. ↩

- On the fear of concentrating the Jewish population vis-à-vis the Allied bombing, see: Cole, Holocaust City, 83. ↩

- See relevant decrees and sources on the website of the Budapest City Archives: https://holocaust.archivportal.hu/temak/ki-kell-menni-zsidonak-lakasabol-csillagos-hazak-kijelolese-budapesten. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 813. ↩

- Cole, Holocaust City, 131–133. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 814. ↩

- Ernő Munkácsi, Hogyan történt? Adatok és okmányok a magyar zsidóság tragédiájához (How it happened: Documenting the tragedy of Hungarian Jewry), (Budapest: Park, 2022), 227. ↩

- Cole, Holocaust City, 166. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 914–915, 927. ↩

- János Solymossy (1912–?) was a police sergeant who was appointed ministerial commissioner responsible for concentrating the Jews of Budapest on 17 November 1944. In this capacity, he was in direct touch with the Jewish Council and helped with the organization of the ghetto. ↩

- Hungarian Jewish Archives (Magyar Zsidó Levéltár, MILEV) XXXIII-5-c, the Jewish Council’s memorandum, 19 November 1944. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, Call to the capital’s Jewish inhabitants, November 1944. ↩

- Budapesti Közlöny vol. 78, no. 250 (1944): 2–4. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 932. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, note about János Solymossy’s report, 24 November 1944. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, call to the non-Jews moving out of the ghetto territory, November 1944. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, note about János Solymossy’s report, 23 November 1944. ↩

- Cole, Holocaust City, 211. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 937. ↩

- See photos of the wall: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/jewish-ghetto-wall-budapest-hungary. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 938. ↩

- A list compiled by the Jewish Council enumerates 17 such buildings, some of which were factories, non-Jewish institutions, while others were the shops of non-Jewish merchants. MILEV XXXIII-5-c. ↩

- See the addresses of the district headquarters and the list of district leaders among the ghetto documents: MILEV XXXIII-5-c, lists of ghetto districts. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, meeting minutes from 3 December 1944. ↩

- Miksa Domonkos (1890–1954) mechanical engineer, lieutenant, member of the Jewish Council. He received exemption from the anti-Jewish laws from Regent Miklós Horthy. During the Arrow Cross era, he was one of the leaders of the ghetto and he became famous for his courageous behavior while protecting the Jews. His testimony can be read here: http://degob.hu/index.php?showjk=3662. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, decree, 5 January 1945. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, reports of the ghetto police commander to the Jewish Council. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, reports from 6 January 1945 and 17 January 1945. ↩

- See: MILEV XXXIII-5-c, the Jewish Council’s letter to János Solymossy, 25 November 1944. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 943–944. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, dietary norms in the ghetto. ↩

- See the request of the ghetto police headquarters asking for candles and reporting that in seven ghetto districts there is no electricity. 28 December 1944. MILEV XXXIII-5-c. ↩

- Gábor Ács, “Séta az egykori gettó utcáin” (A walk on the streets of the former ghetto), Euronews.com, https://hu.euronews.com/2021/01/27/zarva-a-bulinegyed-most-csendes-setan-emlekezhetunk-a-getto-utcain-a-holokauszt-aldozatair. ↩

- Cole, Holocaust City, 219; MILEV XXXIII-5-c, Miksa Domonkos’s letter to the district leaders, 14 January 1945. ↩

- Braham, A népirtás politikája, 946. ↩

- Ibid. 945. ↩

- MILEV XXXIII-5-c, instructions of the ghetto department for burials, 4 January 1945. ↩

Tzipporah Bat-ami

Thank you for this information. My uncle was still involved in the Budapest area sleeping in the bldg where he made the false passports at night. My father was in concentration camps and survived in part due to American beds where he could rest. He and his brother then made it to meet their brother. Thank you for.your work.

Bori

Thank you! Do you perhaps remember which building this was?

Miriam bak

My late mother lived in 22 Wedselenyi utca renting a room from a non Jewish woman.She left her town of Biel to earn money as a seamstress for the family back home.She was 18 and had false papers hiding her Jewish identity.I would love to know what hat happened to that building.Was told it was bombed?When? And what is the new building number 22 on the site?

Bori

Dear Ms Bak,

I found the following information at https://mierzsebetvarosunk.blog.hu/2016/09/16/wesselenyi_utca_20_22:

“At 22 Wesselényi street, Simon Steiner soap maker’s house stood which was broadened in 1862 with an open shed, based on Károly Hild’s plans. In 1867, a soap factory was built in the courtyard, based on József Limburszky’s plan. The building was dismantled in 1983.”

Today, there is a new building, taking up the plots of 20-22 Wesselényi street, built by OTP.

I don’t have information about the original building being bombed down, but I have the list of tenants from the post-war census of damage assessment: Ferenc Feith, widow Mrs. Ferenc Weber, Mrs. Bernát Geisler, Mrs. Jenő Zucker, László Feith, Mrs. Lajos Fiedler, Jolán Klein, Hermann Grünberger.