For Holocaust history, the territory of Ukraine is one of the crucial spaces. By the middle of 1941, about 2.7 million Jews were living in the territory of what today is the independent state of Ukraine, including the Crimean peninsula. Only about 100,000 of them survived the war in areas under German rule. In less than two years, about 60% of Ukraine’s pre-war Jewish population was murdered.

Taking this into account, already in 2015 the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) devoted a chapter in its Online Course in Holocaust Studies to the Holocaust in Ukraine. This special series of the EHRI Document Blog aims to further advance this research direction and create a space for Ukrainian Holocaust researchers to present their latest results, especially in these extraordinarily tough times.

Immediately after the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, EHRI issued a statement in which it strongly condemned the unprovoked and inexcusable attack on a sovereign country. Simultaneously, EHRI started to explore ways to help Ukrainian scholars at risk and make Ukraine and its researchers more visible in the field of Holocaust Studies, including this special series in the EHRI Document Blog. It works closely together with its Ukrainian partner institution, the Center for Urban History in Lviv.

When German troops occupied the city of Zvenigorodka (Cherkasy Oblast) on July 29, 1941, approximately 1,300 local Jews and refugees from the west lived there, which was just over ten percent of the total population. There were no spontaneous pogroms here; instead, Nazi occupiers forced all Jews to register and sent them to forced labor in the city. They lived in their homes until September, when, on the orders of the military commandant, the German and Ukrainian auxiliary police forces drove all the Jews into the ghetto. The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police guarded them.1

The Krasylovski family was among the forcibly resettled Jews. According to the evidence of their daughter, Liubov Krasylovoska, who was still a child at the time, local non-Jews sometimes came to them to exchange goods or to commit common robbery. One day their prewar neighbor named Hryshko, now a policeman, entered the house. He demanded a new blanket from Liubov Krasylovska’s mother, which she was supposed to knit for him. The woman replied that she did not have anything like that at the moment. The policeman became angry and began beating the woman. When he finished, Hryshko tied the woman up and left the house, but he soon returned with German soldiers and forced Liubov Krasylovska to dig a hole for her own mother. The woman asked to say goodbye to her child, to which the policeman replied: “Shut your Jewish muzzle, you tortured us for 23 years.”2 After these words, he shot the woman with a pistol, and then he decided to “finish” her off with explosive bullets shot from a rifle. The events unfolded before Liubov Krasylovska’s eyes. There was no order, as she claimed during the postwar interview, from the German authorities to shoot her mother.3 This demonstrates the role of the personal initiative of auxiliary policemen in participating in the Holocaust on a local level. During the analysis of thematic sources, such as the testimonies of eyewitnesses and victims of German occupation policy, one often finds information about local perpetrators.

However, in cases when the testimony did not directly provide identifying information about specific perpetrators, only the collective name “policemen” appeared. Turning to the historiography, I was surprised by the variety of different terms that existed to denote the auxiliary police. That is why the problem of determining the definition of the term “auxiliary police” is relevant because there is no universal explanation to date. The name itself hides the variety of military police formations that operated both under the auspices of various German police authorities and outside their influence.

Organization

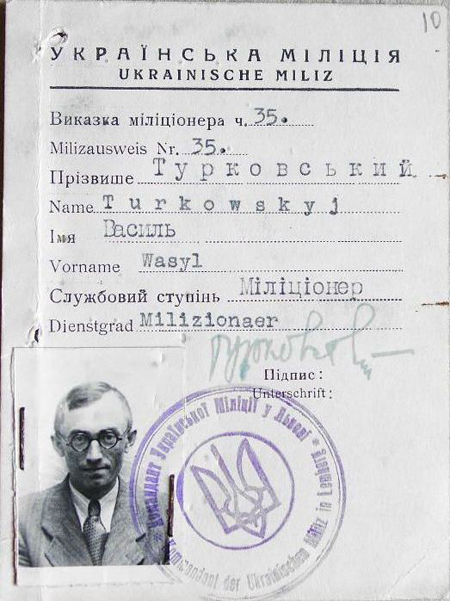

The formation of Ukrainian police units dates back to the Nazis’ campaign in Poland. As a result of repeated requests from representatives of pro-Ukrainian forces, the German authorities established the first police academy in Zakopane in December 1939. However, The Polish police remained the main auxiliary force of the General Governorate (GG). The only region in the GG, where the main institution was the Ukrainian police, was the Distrikt Galizien (now Western Ukraine), which was annexed after the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union.4 At the beginning of their existence in the occupied territories of Ukraine, the local police units were called the Ukrainian National Militia, or simply militia (Miliz). The Ukrainian case was not unique, because, for example, the Lithuanian police, formed by local nationalists from the Lithuanian Activist Front, was initially called the Lithuanian Order Police (litauischen Ordnungsdienst). A few months later it was replaced by German authorities by the Lithuanian Auxiliary Police (Schutzmannschaft).5

The Ukrainian National Militias were created according to three typical scenarios. The first and the most common was the organization of militia by members of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). On the eve of and during the war, the nationalists issued a number of instructions, such as Banderite’s “Struggle and Activity of the OUN During the War.” According to the text, one of the key activities of the organization was to organize the work of the militia. In general, both the OUN, which split in early 1940 between the younger Galicia nationalists (OUN(B), or Banderites) and the older war émigré (OUN(M), or Melnykites), considered the militia to be the core of the future Ukrainian army, the creation of which would help develop an independent Ukrainian state. Strictly speaking, the ultimate ideological goal of Ukrainian integral nationalism was an independent state. There was also a second scenario, according to which the militia was organized by local residents from the region during the period of interregnum, that is, between the retreat of the Soviet government and the arrival of the German army. In this case, the creation of the militia had no political implications and the main reason was the protection of civilians from marauders and bandits. Finally, the third scenario – the formation of the local police force, which took place after the arrival of German troops, by order of the local commandant’s office.6

The announcement by the leadership of the Banderites faction of OUN of the “Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State” on June 30, 1941, provoked the Germans to launch mass repressions against them. As a result, even though the policemen cooperated with the German representatives on the ground, the central leadership of the SS and police apparatus disbanded all active police units and formed auxiliary police on German terms. As John-Paul Himka correctly insists, the OUN militia the German-organized Ukrainian Auxiliary Police that later replaced, it should be distinguished due to the difference in the formation processes and recruitment; the leading personnel of the militia was OUN, which fully determined the tasks of militiamen. However, as the sources and the historiography show, there are practically no real differences between the activities and personnel of both the nationalist militia and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. A significant proportion of former policemen continued their service in the ranks of the police; even Ukrainian nationalists, against whom the Germans launched repressions in the summer and autumn of 1941, sometimes continued to maintain a strong influence on the police. Moreover, not only do the official instructions of the OUN regarding the creation of a local militia not contradict the functions that the Germans entrusted to the auxiliary police, but they almost repeat them completely.

The extensive network of the Third Reich’s police apparatus spread to the occupied territories of the USSR. In particular, the arrests and executions of Jews were carried out by members of the Einsatzgruppen (in the Reich Security Main Office, RSHA), Gendarmerie, or German city police (Schutzpolizei) under the control of the Order Police (Ordnungspolizei), Secret Military Police (GeheimeFeldpolizei), as well as auxiliary police. In each region, the auxiliary police were named differently. An understanding of this can help identify the location of a particular group of auxiliary police and the time and institutional affiliation of the “police” in question. For instance, in the northwestern regions of the occupied regions of the USSR (the area of operation of Army Group “North” and “Center”), which were under the authority of the military administration, the local Belarusian and Russian auxiliary police were called Ordnungsdienst (OD); in the southeastern regions of Ukraine, also occupied by the military administration, the German authority used the term Hilfspolizei (Hipo, UHP).7 In the military administration zone, the auxiliary police were often subordinated to the Wehrmacht security division operating in the area, including local commandants (Ortskommandantur) and Geheime Feldpolizei. In the areas controlled by the civilian administration, namely Reichskommissariat Ostland and Reichskommissariat Ukraine, the police were subordinated to the local SS and police leader (SSPF). Based on the decree of November 6, 1941, the name Schutzmannschaft was finally established for the auxiliary police in these areas, adding geographic prefixes to the name, such as litauische (Lithuanian), weißruthenische (Belarusian), ukrainische (Ukrainian), etc.8 Despite the difference in names, all these formations were de facto “auxiliary police,” as they performed the corresponding functions (from traffic control to direct participation in the Holocaust).

Institutionalization

Historians have frequently focused only on the transformation of the Ukrainian National Militia into Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, ignoring the issue of institutionalization. They often limit themselves to naming “Ukrainian Auxiliary Police,” avoiding deeper investigation of the police structure and assigning duties among different institutions. In the case of auxiliary police in big cities, this is particularly important in precisely identifying the perpetrators of the Holocaust. For instance, after the repression of the Melnykites in Kyiv in February of 1942 and their further removal from the main positions, there was no single Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. Instead, there were three separate institutions that sometimes interacted with each other on official matters.

First of all, the Ukrainian Protection Police (Ukrainska Okhoronna Politsiia, UOP), or Schutzmannschaft des Einzeldienst, was responsible for law enforcement, street patrols, and various auxiliary tasks (e.g., raids to forcibly abduct the local population to work in Germany). When the literature and sources refer to the “Ukrainian police” it most likely means the UOP. Its employees often appear in various photographs, because they were the most numerous branch of the auxiliary police. By July 1943 the UOP forces in Lviv numbered 860 employees; in Kyiv, this figure reached up to 1,400 policemen.9 The UOP in large cities operated under the control of the German city police (Schutzpolizei), and in villages and small towns, under the control of the Gendarmerie. Both the Gendarmerie and the German city police were part of the German Order Police (Ordnungspolizei). In total, as of November 1942, in Reichskommissariat Ukraine approx. 69,000 Ukrainian policemen were supervised by 9,500 Germans.10

Agents and investigators from the Ukrainian Criminal Police (Ukrainska Kryminalna Politsiia, UKP), or Sicherheitsschutzmannschaft, worked closely with UOP officials. However, in small settlements, there could be no UKP at all. Instead, its activities were represented by one or several specially appointed investigators from criminal and political cases. In large cities, the UKP also functioned under other names, such as the “investigative department” or the “Ukrainian Security Police/Ukrainian Gestapo,” which offer eloquent clarity on the nature of its agents and investigators’ activities. As well as the UKP, the employees of the German Criminal Police (Kripo) were involved in the Holocaust as part of various police formations, in particular the Einsatzgruppen. A striking example of this is the head of Kripo, SS Gruppenführer Artur Nebe, who on the eve of the German invasion of the USSR was appointed to the position of commander of Einsatzgruppe B. By November 1941, its members murdered approximately 45,000 people, mostly Jews.11 Therefore, the duties of the UKP included searching, arresting, and interrogating the “political” enemies of Germany—primarily Jews, communists, partisans, and nationalists. The executions of political prisoners were carried out by the UKP’s German-supervising personnel, the German political police (Sipo/SD, which was actually a representation of the RSHA in the occupied territories); in small towns, these responsibilities were assigned to local German institutions (Gendarmerie) or by the auxiliary police. Due to the lack of sources, it is difficult to determine the total number of UKP employees in Ukraine. In the district centers, their numbers were fewer, while in large cities they numbered up to 40 people; in Kyiv, the number was the highest and reached 190 (as of August 1943).12

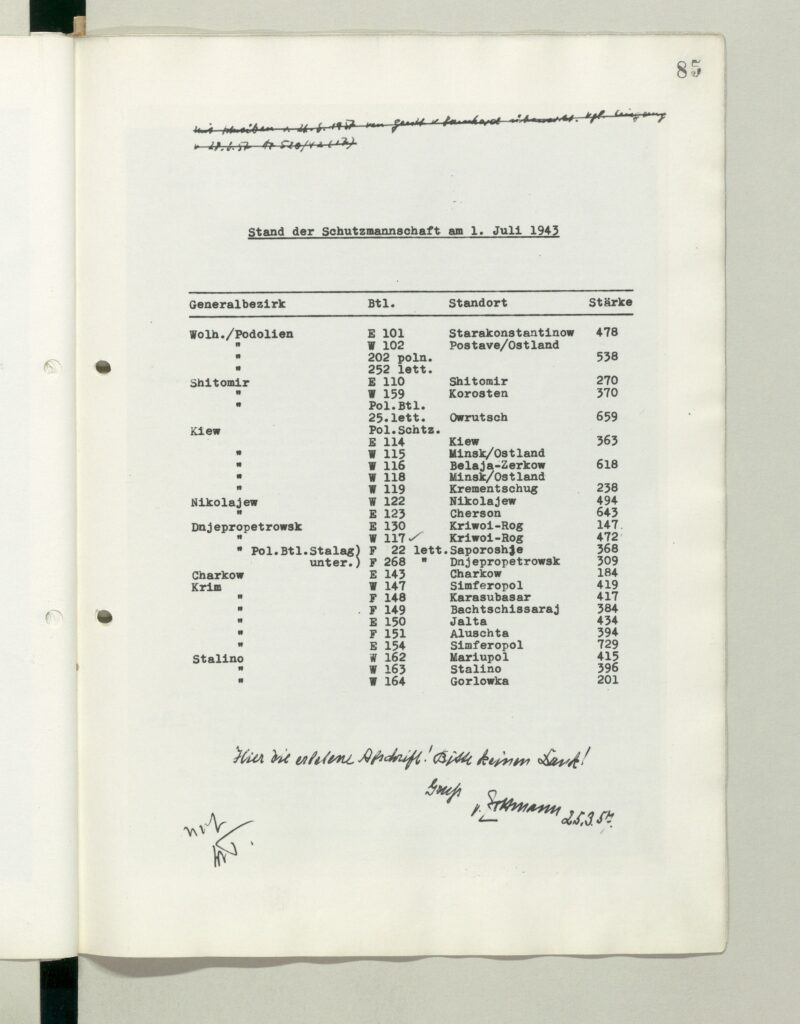

Parts of the so-called mobile police units, or Schutzmannschaft in geschlossen Einheiten, were separated from the UOP and the UKP. The numbering of the auxiliary police battalions (Schutzmannschaft Battalion) indicated the place of their formation or subordination (Reichskommissariat Ostland – No. 1–50; Generalbezirk Weißruthenien – 51–100; Reichskommissariat Ukraine and other territories – 101–200). The vast majority of such units were created under the command of Orpo, but there were also organized a few battalions under Sipo/SD (in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Lutsk). Unlike the UOP and the UKP, whose employees freely returned home during off-duty hours, the fighters of the mobile police units were barracked. As a result, the German authorities could quickly transfer them to different corners of the occupied territories, which made Schutzmannschaft battalions the most movable and combat-ready police institution. Thus, their primary tasks included not only guarding and patrolling tasks but also engaging in anti-partisan warfare.13

Personnel

The first paramilitary units (militia) were mostly organized by both the Bandera and Melnyk factions of OUN. Respectively, Ukrainian nationalists, veterans of the Ukrainian Revolution 1917-21, or anti-Soviet locals were appointed to the main positions. Among the archival collection belonging to the Ukrainian police of one of the villages in the Kyiv region stored instructions, which stated that for the post of commandant, “a well-known nationalist should be chosen,” and all personnel should be recruited exclusively from “conscious Ukrainians.”14 Even though the Germans had already begun reformatting the militia into auxiliary police in the summer of 1941, accompanied by the process of “cleansing” the personnel of nationalists, in some areas their influence spread throughout the whole period of occupation. In Kyiv, almost every employee of the UOP headquarters belonged to the OUN. After two major waves of German repressions toward Ukrainian nationalists, as of July 1, 1942, six of the eleven commandants of the city’s rayons police also belonged to political activists who came from the West.15

In the UOP and some Schutzmannschaft battalions (e.g., the 115th and 118th), so-called “political activists” held management and officer positions (as classified by Alexander Prusin). In addition to the actual members of the OUN, they included representatives of the Ukrainian and Russian war veterans, who emigrated to the West after the Russian Civil War and the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917-21. In the East and South of Ukraine, the Russian right-wing radical National-Labor Alliance (Narodno-Trudovoy Soyuz, NTS) also tried to spread its influence over the auxiliary police. For all the listed groups, police service was a voluntary choice in favor of the fight against the Soviet system and/or a stepping stone in the creation of an independent Ukraine (or Russia in the case of the NTS). Growing up in the context of the general radicalization of political discourse in Europe, their struggle often took place under slogans that identified Jews with Bolsheviks.16

Nevertheless, the vast majority of rank-and-file personnel were not “political activists.” Based on the available literature, it is known that the majority of policemen were local inhabitants – young men of the dominant ethnic origin (Ukrainians) who did not belong to any active political organization.17 There is no single answer to the question of why these people joined the ranks of the auxiliary police. First, it is worth considering the immediate conditions of joining: voluntary or under duress. Voluntary entry was typical for those who saw work in the police as a new social elevator or a way out of the difficult financial situations created by the harsh reality of the occupation.

Many POWs from the Red Army were forced to join the police, trying to save their lives. According to Dieter Pohl’s calculations, between 700,000 and 1,2 million POWs died in the camps for prisoners of war on Ukrainian territory. It meant that, as was the case for the Holocaust, “Ukraine was also the central place of the mass death of Soviet prisoners of war.”18 The lack of alternatives can also be considered a peculiar form of forcing. After the announcement of a campaign for forced mobilization of the population for work in Germany in the spring of 1942, new personnel quickly replenished the ranks of the police. Representatives of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police were present at the points of mobilization meetings of “Ostarbeiters,” who offered the only possible alternative to forced deportation—joining the police service.

Obviously, in conditions where the majority of local collaborators did not belong to “political activists,” it would be wrong to consider the complicity of the local police in crimes only through the lens of Ukrainian integral nationalism ideas. Moreover, motivations for joining the police did not necessarily correspond to policemen’s motives during the service, since the same person during the entire period of occupation could passively observe crimes, actively participate in them, or resist. As for the specific reasons for complicity in mass violence, the subjective side probably consisted of a mixture of ideology (nationalism, antisemitism, anti-Bolshevism), conformity (reluctance to stand out from the crowd, passive compliance with orders), and diversity of personal motivations (hatred toward the exact person). The objective side could be found in the legalization and routinization of crimes (violence against Jews was not punished by the German authorities), as well as in Nazi propaganda (marginalization and dehumanization of Jews). Together or separately, these factors may have guided the choice of police officers to be involved in crimes.19

The collective portrait of the UKP stands in stark contrast to the situation in UOP and mobile units. In the Kyiv example can be noticed three characteristic features of the personnel of the UKP. First, despite the dominance of the Ukrainian population in the city, after registration as a separate institution, official positions in the UKP were partly occupied by persons of non-Ukrainian origin. As it turned out, similar trends can be observed in other large cities: in Lviv, the auxiliary criminal police was almost entirely occupied by Poles; in Zaporizhzhia, one could find a Russian and a Bulgarian among the investigators; depending on the Russian root of the surnames of many investigators, it can be assumed that UKP in Mykolaiv was not an exception either.20 Secondly, a large number of former communists and members of the NKVD were concentrated in the UKP, which is due to the nature of the “political” work (conducting the investigation against the Soviet activists, Jews, and Ukrainian nationalists).21 The Germans were convinced that party membership in the Soviet Union was more a tool for social mobility than an indication of real political convictions. Therefore, in many cities, they used local political assets as unofficial agents or invited them to work with the police. Thirdly, being a part of the German political police (Sipo/SD), the UKP personnel was regularly filtrated and selected. An internal policy in Sipo/SD was designed in such a way as to select the employees most useful to the German authorities. Therefore, among the UKP were proportionally more policemen loyal to the Germans. In those circumstances not surprisingly 16 of 19 leading commanders of the UKP decided to evacuate from Kyiv with the Germans in the autumn of 1943.

Participation of the UOP, UKP, and Police Battalions in the Holocaust

As well as the German-authorized Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, the OUN-controlled Ukrainian National Militia was deeply involved in the Holocaust. As Kai Struve convincingly proved, there was no single scenario for the anti-Jewish violence by Ukrainian nationalists in the summer of 1941.22 It could have been the execution of orders from the German authorities, pre-planned actions by the members of the OUN themselves, or there could have been spontaneous actions of a ritual nature with the support of the local population. The Lviv pogrom is probably the most well-documented case in which militiamen participated. While retreating from Western Ukraine in June 1941, Soviet authorities sanctioned the executions of thousands of “political” inmates at local prisons; some of the victims were OUN members. After the Germans occupied these territories, NKVD crimes were immediately discovered and widely used for propaganda purposes. The Germans artificially increased the antisemitic sentiments of the local gentile population by associating NKVD crimes with Jews. Therefore, mass violence against Jews was conducted under the banner of the struggle against “Judeo-Bolshevism.” Banderites-controlled Ukrainian militia carried out the arrests, physical torture, and murder of Jews during several first days in July 1941.23 Similar cases occurred all the time in the territories of Western Ukraine controlled by German troops, while in the zone of occupation by Hungarian troops the violence did not reach such a scale.24

However, crimes against Jews, committed by militia, were not restricted to Western Ukraine, where the OUN widely penetrated the occupation administration. A well-known source collection of “Messages from the Eastern Occupied Territories” compiled by employees of the Sipo/SD is full of references to the direct participation of the local militiamen in the Holocaust. In Northern Ukraine, for example, on September 6, 1941, in Radomyshl, “1,107 adult Jews were shot by Sonderkommando 4a, and 561 Jewish children were shot by the Ukrainian militia.” Around this same time in Korosten, “238 Jews, who were herded by the Ukrainian militia into special houses, [and] were shot.” Somewhat later, on September 21, members of the Uman militia, together with German soldiers, committed a Jewish pogrom contrary to the plan. “In the course of the events, all Jewish homes were destroyed, from which all valuables were taken.”25 Some literature and sources contain information about the activities of the Ukrainian militia/police in the killing of Jews in Southern Ukraine both under the German and Romanian occupation zone between 1941 and 42.26 Thus, local militiamen were closely involved in mass violence against Jews both under and without control from OUN.

The disbandment of the Ukrainian National Militia departments was finally completed by the end of 1941. In some remote areas, in Eastern Ukraine, this process continued up to the summer of 1942.27 When the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police were finally formed by the German authority, some (or most) of the former militiamen continued to serve. The process of transition of police power from OUN to Germans was accompanied by a decrease in the level of autonomy and the division of responsibilities between the several institutions. This institutional separation was mostly visible in big cities, where the employees of the UOP and UKP were under the constant supervision of German officers, and the violence was clearly regulated. At the provincial level, by contrast, the occupying authorities experienced a critical shortage of German personnel. In other words, the rural auxiliary policemen were given unlimited power, which led to a high level of uncontrolled arbitrariness and violence.28

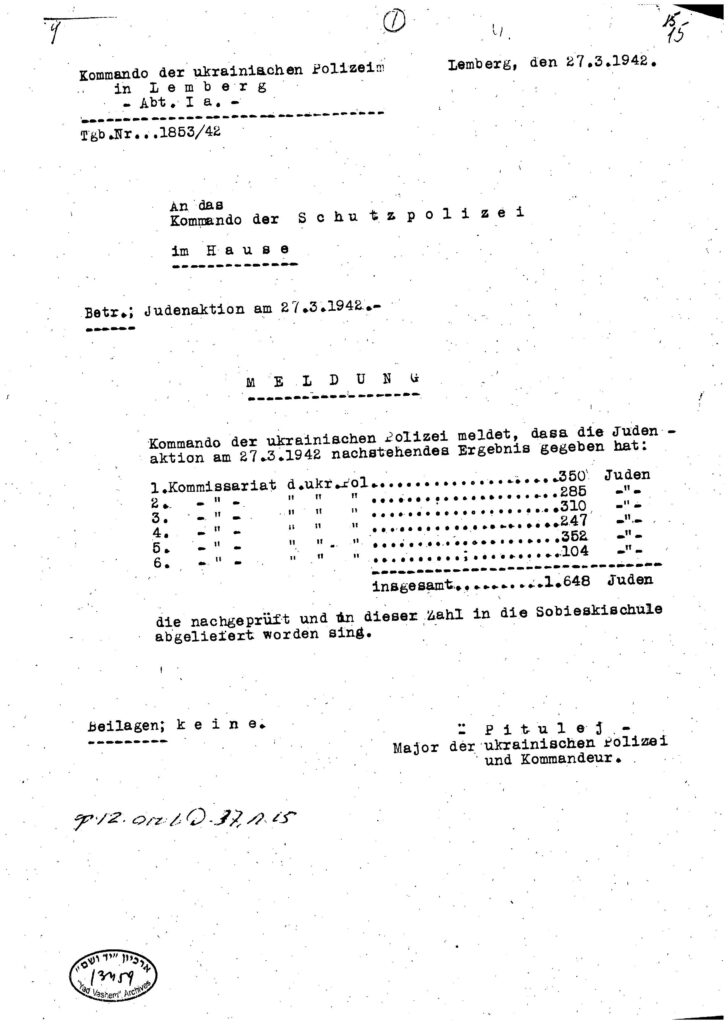

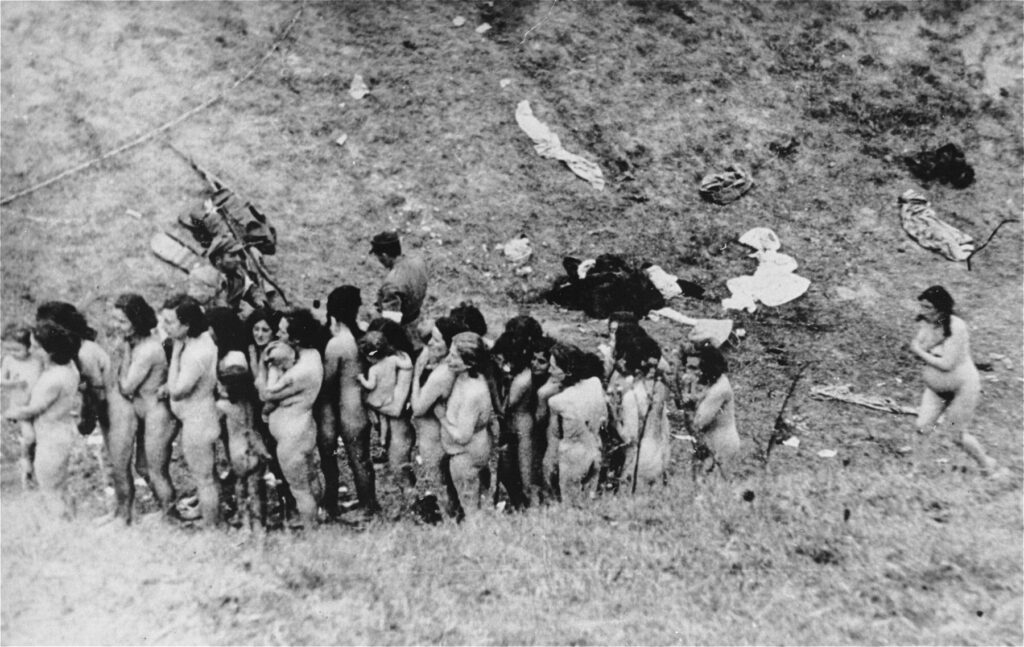

The Ukrainian Protection Police (UOP) officers were entrusted with the task of maintaining law and order, and sometimes, on the orders of the local Sipo/SD branch, they were involved in “political” arrests. This document illustrates the scale of such operations in large cities after the adoption of the “final solution to the Jewish question” (according to the results of the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942). On one day in March 1942 in Lviv, 1,648 Jews were detained. In total, between March and December 1942, about 70,000 Jews were arrested, half of whom were rounded up by the Lviv UOP. Later, the absolute majority of those arrested awaited physical destruction in the Belzec extermination camp.29 It would be wrong to assume that the local collaborators were not aware of what awaited the Jews they detained. Once, during a regular drunken rape by the police, one of them, justifying his own actions, told a Jewish woman imprisoned in the ghetto in Uman, “You all will die here anyway.”30 The members of the UOP took part in rounding up and convoying, as well as in guarding the places of mass executions. For example, the photos below clearly demonstrate the complicity of the Ukrainian police during the shootings of Jews after the liquidation of the ghetto in Mizoch (Rivne region). In total, on October 13-14, 1942, at least 1,700 people were killed. Some of the photographs published in the next part of this contribution display explicit violence primarily to document the crimes committed by the auxiliary police in Ukraine.

The details of local policemen’s participation in criminal activities are best documented by their testimony during (post)war interrogations by NKGB/MGB/KGB. The circumstances of the investigative process, regarding the interpretation of the accuracy of the accused policemen’s words (how “honestly” he recalls, or whether the investigator might blame him for “other people’s” crimes), have repeatedly become the object of criticism by historians.31 Nevertheless, much rarer are the testimonies of local policemen, compiled during the German occupation. A few of them can be found among German captured documentation, for instance, in NARA. In the context of collaborator studies, a noteworthy feature of these sources is confirming the involvement in the mass violence against Jews as an ordinary activity of local policemen. In December 1941, a squad of 35 members of the Chernihiv district police, headed by a commandant named Shylo, went to the nearby village Ponornytsia. One of the policemen stated that “Shylo gave the order to arrest all Jews, confiscate their property, interrogate, search, and shoot them in the basement until 12 o’clock at night. There, Shylo allowed anyone who wanted to take young Jewish women out of our cells and rape them. […] The shooting was immediately carried out after that. […] After the shooting, all goods were collected by [policemen] Borovyk and Shylo, except for gold and watches, and loaded into six wagons. In the morning we left for the village of Korop. The items were deposited in the police warehouse. [Later commandant] Shylo took these goods for himself in unlimited quantities.”32

Other sources and historiography only confirm the symptomatic nature of this case for most of the provincial districts of the occupied territories of the USSR. The policemen from rural areas raped women, appropriated property, and shot Jews without any sanction from above. According to the observations of John-Paul Himka, similar cases were more common in the territory of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine than in Eastern Galicia.33

Among all of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police branches, the historical intelligence situation regarding the UKP is the most critical. Paradoxically, according to the historian Jan Grabowski, the Polish Protection Police (or Policja granatowa) has already been considered by researchers more than once. At the same time, on the Polish Criminal Police (Polnische Kriminalpolizei), whose activities are directly and significantly more related to the extermination of the Jewish population on the territory of the General Governorate, almost nothing is mentioned in historical literature.34 The same unexplored niche can be seen in the example of the Ukrainian Criminal Police (UKP).

The UKP agents were engaged in external surveillance, identification, search, arrests, and escorting detainees to the police station or headquarters. By using all available modus operandi, investigators from UKP tried to force a person to tell whatever was needed. In one of the districts of the Kyiv region in January 1943, an investigator beat up a detainee in order to learn the truth about the origins of his Jewish wife.35 However, the activities of the UKP often did not end with physical violence alone. In Kyiv, the head of the investigative department, Roman Bida (Melykites, pseudonym “Hordon”), was present during the mass shootings in Babyn Yar, and in the midst of active hunting for surviving Jews, he wrote a letter to the city commissar with a request, “to account for the Jewish-Bolshevik danger in the city, to establish a prison and a concentration camp in the city in order to be able to isolate uncertain elements.”36 In Kryvyi Rih, Vasyl Pasternak, the head of the UKP, “actively participated in torture and personally went to the executions of local residents,” as well as kept the looted property of murdered Jews. The senior investigator of the Kamianets-Podilskyi department of the UKP of Ukraine, Persiyanov, was a direct participant in mass shootings of the civilian population, including Jews.37

As in the case of the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police in general, historians were mostly interested in those military-police units whose activities caused a wave of public discussion. In particular, this applies to the 115th, 118th, and 201st Schutzmannschaft battalions, which could have been involved in the Holocaust in Belarus. They suggest that the policemen of the battalions were involved in mass shootings of the civilian population under the guise of bandits or their “helpers.” Moreover, for a while the 115th and 118th battalions were assigned to the infamous combat group “von Gottberg” (Kampfgruppe von Gottberg) under the command of the SS and police leader of the Generalbezirk Weißruthenien, SS-Brigadierführer Kurt von Gottberg.38 Von Gottberg’s chosen methods for conducting anti-partisan warfare were genocidal in nature and are best characterized by his own words: “Bandits, locals suspected of banditry, and loyal to bandits Jews, gypsies, horsemen [sic], and minors should be considered spies.”39 The German term “partisans,” which was replaced with the euphemism “bandits” by Himmler’s order in August 1942, included wide interpretation. In other words, anyone from the civilian population, regardless of age and gender, could actually become a potential candidate for destruction. As Alex J. Kay noted, during anti-partisan operations, “German forces massacred hundreds of thousands of Soviet civilians, destroying thousands of homes and, indeed, entire villages in the process, more than 600 in Belarus alone. The vast majority of the victims of these massacres had little or no connection to guerrilla resistance, and virtually all of these deaths had a racist component.”40

The history of other Schutzmannschaft battalions, such as the 116th and 124th, was researched by Ivan Dereiko. He concluded that the policemen of both were involved in convoying, arrests, and direct executions of both the Jewish and non-Jewish populations of Kyiv and Vinnytsia regions, respectively.41 In addition, according to Dieter Pohl, the 102nd, 103rd, and 117th Schutzmannschaft battalions also took part in mass shootings on the territory of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, in particular in the area of the strategic road Durchgangsstraße IV.42 Crimes of other mobile police units, which were recorded during post-war trials of collaborators, remain uninvestigated. For instance, the 1st company of the 108th Schutzmannschaft battalion took part in the shooting of the Jews of the Korets ghetto (Rivne region), which took place on May 21, 1942. During the post-war Soviet investigation, one of the former policemen of the battalion testified about this in the following way:

“[…] when the entire Jewish population [of Korets] was driven to the square, the Germans selected among them the able-bodied, first of all, men, and then women in the amount of up to 1,000 people. […] Germans and policemen took up to 2,000 women, children, and elderly people unable to work due to age or illness, in groups of 200 people or more, to the forest located 5-6 km away from the district center and they shot them there […] I personally undressed the Jews and shot 5 people with a rifle.”43

In total, about 2,500 Jews were shot that day. The perpetrators of the massacre from among the 108th Battalion are not mentioned in the historiography.44

Finally, it is necessary to say a few words about rescue. Undoubtedly, the historiography describes many cases of help from the police, which they provided to victims of Nazi terror. Nevertheless, ordinary residents’ perception (and even more so of the Jewish nationality), is that this was a deviation from normal behavior. During an interview in 2006, Anatoliy Tymoshenko recalled that during the German occupation in Kyiv, “There was one policeman living in our house, but everyone said he was good.”45 In these words, one can see the existence of a certain degree of “presumption of guilt,” when negative connotations were applied to all police officers a priori. In most cases, this concerns inhabitants’ opinions in the territory of Ukrainian SSR in the borders as of September 1, 1939. According to some historians, the situation in Eastern Galicia was fundamentally different from other regions, not least because of the pre-war radicalism of Polish authority, OUN influence, and a more gentle occupation regime toward Ukrainians. Therefore, the mood of the local population “increasingly resembled a simulacrum of Nazi society, since the cumulative dynamics of this emerging society, like Nazi society, was to unswervingly divide the world into friends and enemies, hunt down these enemies, and redistribute social capital through violence.”46

Conclusions

Several main conclusions can be drawn from the above. Firstly, during the German occupation, there was no single “Ukrainian Auxiliary Police.” Instead, it was divided into UOP, UKP, and mobile police units, which was especially visible in the example of large cities. Each of these institutions had its own range of responsibilities: patrol service in the UOP; investigative, agency, and political work in the UKP; and the anti-partisan activities of the mobile police units. Nevertheless, in small settlements, the division into such institutions could not exist, and the entire executive and judicial power was simultaneously concentrated around the local police department.

Secondly, the pages of pre-war biographies may be important for understanding the motives of the collaborators, but from the perspective of the collective, they did not play a decisive role. After all, a new social category was formed, intermediate between the German authorities and the local non-German population—auxiliary workers of the occupation authorities. The emergence of a new, “corporate identity” can explain the blurring of mental boundaries and allows us to understand why Ukrainian nationalists, Soviet communists, careerists, and ordinary workers and peasants cooperated in the service of the auxiliary police. As can be seen from the sources and literature, all the listed groups were simultaneously involved in the destruction of the “political enemies” of the Third Reich.

Thirdly, both the OUN militia and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police created on its basis are directly and indirectly responsible for the Holocaust at the local level. Cases of mass violence are recorded in all corners of the occupied territories of Ukraine. Members of the UOP were engaged in identification, arrests, guarding, and escorting Jews to places of execution; under the control of the German political police, investigators and agents of the UKP carried out arrests and interrogations of prisoners; policemen of mobile units were involved in shooting Jews, and also went on anti-partisan operations, during which there were precedents of extermination of the local population under the guise of “bandits.” Depending on the local situation, the functions of all three could change, combine, or be replaced.

In general, in the past few decades, the issue of collaboration of the local population in the Holocaust has become increasingly popular among historians. However, taking into account the lack of information on auxiliary police personnel of cities and districts, the study on the micro level looks promising.

Translated by Amber N. Nickell

- Alexander Kruglov and Alexander Prusin, “Zvenigorodka,” in Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Volume II: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe Part B Eastern Europe, Part B, eds. Geoffrey P. Megargee, Martin Dean, and Mel Hecker (Indiana University Press; USHMM, 2012), 1611. ↩

- Lubov Krasilovskaya, United State Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Oral History, 1995.A.1287.16, File RG-50.226.0016, 01:09-01:23. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn511923. Viewed 09.12.2022. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Gabriel Finder, and Alexander Prusin, “Collaboration in Eastern Galicia: The Ukrainian Police and the Holocaust,” East European Jewish Affairs, 34 (2004): 103–105. ↩

- National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), T175, roll 233, frame 2721493-2721498 (“Ereignismeldung UdSSR, Nr. 21, 13 Juli 1941”). ↩

- For the first two scenarios, see.: John-Paul Himka, Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust. OUN and UPA’s Participation in the Destruction of Ukrainian Jewry, 1941–1944 (Ibidem Press, 2021), 219–228. An example of the third: Yuri Radchenko, “«Ukrainische Hilfspolizei» i Holokost na territorii general-betsirka Chernigov, 1941–1943 gg.,” Forum noveyshey vostochnoevropeyskoy istorii i kulturyi. Russkoe izdanie, 1 (2013): 302. ↩

- Example of use: OD: NARA, T175, roll 233, frame 2722155 (“Ereignismeldung UdSSR, Nr. 70, 1 September 1941”); Example of use: UHP: NARA, T175, roll 235, frame 2724061 (“Ereignismeldung UdSSR, Nr. 185, 25 März 1942”). ↩

- The name Schutzmannschaft appears for the first time in the order by the chief of police, Kurt Daluege, dated July 31, 1941: BArch, RW 41/4, Bl. 64 (“Schutzformationen in den neuen Ostgebieten, 31 Juli 1941”). ↩

- Gabriel Finder, and Alexander Prusin, “Collaboration in Eastern Galicia: The Ukrainian Police and the Holocaust,” East European Jewish Affairs, 34 (2004): 106; NARA, T315, roll 1634, frame 958 (“Übersicht aller im Bereich Stadt-Kdtr. Kiew befindlich deutschen Polizeistreifen sowie der ukrainischen Hilfskräfte, 5.03.1943”). ↩

- “Abschnitt 13. Ukraine (Russland-Süd)” in Waffen-SS und Ordnungspolizei im Kriegseinsatz 1939-1945. Ein Überblick anhand der Feldpostübersicht, bearb. G. Tessin, N. Kannapin, B. Meyer (Osnabrück, 2000), 593. ↩

- Michael Wildt, An Uncompromising Generation: The Nazi Leadership of the Reich Security Main Office (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2010), 172. ↩

- Calculated by: Anatolii Pohorelov, “Oblychchia smerti: Teror politsii bezpeky ta SD proty naselennia heneralnoi okruhy ‘Mykolaiv’,” Problemy istorii Holokostu: ukrainski vymir, 11 (2019): 109; HDA SBU, f. 11, spr. 769, t. 14, ark. 127–133 (“Spysok na oderzhannia paika spivrobitnykiv Politsii Bezpeky, Kryminalnyi viddil m. Kyieva z 1 serpnia po 10 serpnia 1943 roku”). ↩

- Learn more about the formation and structure of the OUP and UKP mobile units here.: Ivan Dereiko, Mistsevi formuvannia nimetskoi armii ta policii u Raikhskomisariati ‘Ukraina’, 1941–1944 roky (Kyiv: Instytut istorii Ukrainy NAN Ukrainy, 2012), 64–83. ↩

- DAKO, f. R-2053, op. 1, spr. 3, ark. 24 (“Instrukciia Narodnoi militsii (na seli)”). ↩

- Daniil Sytnyk, “Formuvannia ukrainskoi politsii v Kyievi (1941-1943),” Naukovi zapysky NaUKMA: Istorychni nauky, 3 (2020): 43–44. ↩

- Aleksandr Prusin, “Ukrainskaya politsiya i Holokost v generalnom okruge Kiev, 1941–1943: deystviya i motivatsiya,” Holokost i suchasnist”. Studii v Ukraini i sviti, 2 (2007): 43–46. ↩

- David Rich, “Armed Ukrainians in L’viv: Ukrainian Militia, Ukrainian Police, 1941 to 1942,” Canadian-American Slavic Studies, 3 (2014): 280–281; Aleksandr Prusin, “Ukrainskaya politsiya i Holokost v generalnom okruge Kiev, 1941–1943: deystviya i motivatsiya,” Holokost i suchasnist”. Studii v Ukraini i sviti, 2 (2007): 46–47; Yuri Radchenko, “«We Emptied our Magazines into Them»: The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police and the Holocaust in Generalbezirk Charkow, 1941–1943,” Yad Vashem Studies, 41, 1 (2013): 84–86; Yuri Radchenko, “Ukrainska politsiia ta Holokost na Donbasi,” Ukraina Moderna, 24 (2017): 99. ↩

- For more details, see: Dieter Pohl, “Life and Death of Soviet POWs in Occupied Ukraine 1941-1944” (Paper for the Conference Camps in the Occupied Soviet Union 1941-1944, Paris 19-20 September 2011). ↩

- These conclusions are based on the approaches proposed by Christopher Browning. See: Christopher Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 159–189.

The situation in the UKP (or “investigation department”) was completely different. Their leadership also belonged to the OUN at first, but as a result of German repression, the nationalists became a target of persecution by their former colleagues. In Kyiv, the criminal commissar of the UKP, Mykola Pylypenko, participated in the development of his fellow nationalists, who were shot after mass arrests during the operation on March 3, 1943. Even the chef of Sipo/SD in Kyiv SS Sturmbannführer Erich Erlinger personally took part in this action. In Vinnytsia, Andriy Matkovskyi, head of the political department of the UKP, first joined the Banderites, and later “betrayed” the group by passing information about them to the German leadership. Such cases were observed in other cities, including Mariupol.[20. HAD SBU, f. 5, spr. 56258, ark. 106; “Vytiah iz ahenturnoho donesennia ahenta ‘Tamara’ pro orhanizaciinu strukturu i kadrovyi sklad kryminalnoi politsii periodu tymchasovoi natsystskoi okupatsii m. Vinnytsi, 21 kvitnia 1944 r.,” in Nasylstvo nad tsyvilnym naselenniam. Vinnytska oblast. Dokumenty orhaniv derzhbezpeky. 1941-1944. Upor. Valeri Vasyliev et all (Kyiv: Vydavets V. Zakharenko, 2020), 139; Yuri Radchenko, “Ukrainska politsiia ta Holokost na Donbasi,” Ukraina Moderna, 24 (2017): 81. ↩

- Taras Martynenko, “Ukrayinska Dopomizhna Politsiia v okruzi Lviv-misto: shtrykhy do socialnoho portreta,” Visnyk Lvivskoho universytetu. Seriia istorychna, 48 (2013): 154; Roman Shliakhtych, “Zaluchennia chleniv ukrainskoi dopomizhnoi policii do masovykh ubyvstv ievreiv na terytorii Raikhkomisariatu ‘Ukraina’,” Problemy istorii Holokostu: ukrainski vymir, 13 (2021): 95; Anatolii Pohorelov, “Oblychchia smerti: Teror politsii bezpeky ta SD proty naselennia heneralnoi okruhy ‘Mykolaiv’,” Problemy istorii Holokostu: ukrainski vymir, 11 (2019): 108. ↩

- For example, see: HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 59410, ark. 10–10 zv.; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 59418, ark. 20; HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 53528, t. 3, ark. 145. ↩

- Kai Struve, Nimetska vlada, ukrainskyi natsionalizm, nasylstvo proty ievreiv: Lito 1941 roku v Zakhidnii Ukraini (Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2022), 453–456. ↩

- Ibid., 355–356. ↩

- Ibid., 537. ↩

- NARA, T175, roll 233, frame 2722434 (“Ereignismeldung UdSSR, Nr. 88, 19. September 1941”); Ibid., frame 2722298 (“Ereignismeldung UdSSR, Nr. 80, 11 September 1944”); NARA, T175, roll 234, frame 2722975 (“Ereignismeldung UdSSR, Nr. 119, 20 Oktober 1941”). ↩

- Roman Shliakhtych, Roman Mykhalchuk, “Local Police and the Holocaust in the Genral District ‘Dnipropetrovsk’ (Evidence from the Districts of Kryvyi Rih and Stalindorf),” INTERMARUM: history, policy, culture, 11 (2022): 86–98; Diana Dumitru, The State, Antisemitism, and Collaboration in the Holocaust: The Borderlands of Romania and the Soviet Union (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 227–228. ↩

- Yuri Radchenko, “«We Emptied our Magazines into Them»: The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police and the Holocaust in Generalbezirk Charkow, 1941–1943,” Yad Vashem Studies, 41, 1 (2013): 74. ↩

- Martin Dean, Collaboration during the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941–44 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), 70. ↩

- David Rich, “Armed Ukrainians in L’viv: Ukrainian Militia, Ukrainian Police, 1941 to 1942,” Canadian-American Slavic Studies, 3 (2014): 283. ↩

- Gertruda Mostovaya, USHMM, Oral History, 2005.595.57, File RG-50.575.0057, 01:04:30. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn44965. accessed 09.12.2022. ↩

- For example, see: Ivan Dereiko, “Arkhivno-slidchi spravy iak dzherelna baza doslidzhennia osobystoho vymiru proiaviv zbroinoho kolaboratsionizmu v Raikhskomisariati ‘Ukraina’,” Storinki voiennoi istorii Ukrainy, 13 (2010): 33–39. ↩

- NARA, T501, roll 32, frame 282 (“Pokazania hr. Ovsienko Anatoliia Vasylevicha”) ↩

- John-Paul Himka, Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust. OUN and UPA’s Participation in the Destruction of Ukrainian Jewry, 1941–1944 (Ibidem Press, 2021), 332. ↩

- Jan Grabowski, Na posterunku. Udział polskiej policji granatowej i kryminalnej w zagładzie Żydów (Wołowiec: Wydawnictwo Czarne, 2020), 18. ↩

- Oleksi Honcharenko, Holokost na terytorii Kyivshchyny: zahalni tendentsii ta rehionalni osoblyvosti (1941–1944 rr.). Dysertatsiia na zdobuttia naukovoho stupenia kandydata istorychnykh nauk (Pereiaslav, 2005), 164. ↩

- Citation for: DAKO, f. R-2356, op. 1, spr. 53, ark. 11 (“Zapyt shefa slidchoho viddilu Komandy Ukrainskoi policii do komisara m. Kyieva shchodo stvorennya v misti viaznytsi ta kontstaboru 13 lystopada 1941 r.”). ↩

- Roman Shliakhtych, “Zaluchennia chleniv ukrainskoi dopomizhnoi policii do masovykh ubyvstv ievreiv na terytorii Raikhkomisariatu ‘Ukraina’,” Problemy istorii Holokostu: ukrainski vymir, 13 (2021): 100, 107; “Svidchennia kolyshnoho politseiskoho F. Zalohy pro osobovyi sklad natsystskykh okupaciinych orhaniv na terytorii Kamianets-Podilskoi oblasti,” in Nasylstvo nad tsyvilnym naselenniam. Khmelnytska Oblast. Dokumenty orhaniv derzhbezpeky. 1941-1944. Upor. Valeri Vasyliev et all (Kyiv: Vydavets V. Zakharenko, 2022), 136. ↩

- See more details: Per Anders Rudling, “Terror and Local Collaboration in Occupied Belarus: The case of Schutzmannschaft Battalion 118. Part One: Background,” Historical Yearbook, Nicolae Iorga History Institute, Romanian Academy, Bucharest, VIII, (2011): 195–214.; Per Anders Rudling, “Navuka zabivats: 201-yi batal’en akhounai palitsyi i hauptman Raman Shukhevich u Belarusi u 1942 hodze,” ARCHE, 7-8 (2012): 67–87. ↩

- Citation for: Hannes Heer, “The Logic of the War of Extermination: The Wehrmacht and the Anti-Partisan War”, in War of Extermination: The German Military in World War II, 1941-1944, eds. Hannes Heer and Klaus Naumann (New York: Berghahn Books, 2000), 113. ↩

- Alex J Kay, Empire of Destruction: A History of Nazi Mass Killing (Yale University Press, 2021), 183. ↩

- Ivan Dereiko, “Vid ukrainskoho kurenia Biloi Tserkvy do pozhezhnoi sluzhby Berlina: dolia 116-ho batalionu shutsmanshaftu,” Storinki voiennoi istorii Ukrainy, 17 (2015): 56; Ivan Dereiko, “«Chorna sotnia» Kirovohrada: istoriia 124-ho batalionu shutsmanshaftu,” Storinki voiennoi istorii Ukrainy, 18 (2016): 49. ↩

- Dieter Pohl, “The Murder of Ukraine’s Jews under German Military Administration and in the Reich Commissariat Ukraine,” in The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization., eds. Ray Brandon and Wendy Lower (Indiana University Press; USHMM, 2008), 55. ↩

- HDA SBU, f. 5, spr. 64268, ark. 63. ↩

- Alexander Kruglov and Andrew Koss, “Korzec,” in Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Volume II: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe Part B Eastern Europe, Part B, eds. Geoffrey P. Megargee, Martin Dean, and Mel Hecker (Indiana University Press; USHMM, 2012), 1386. ↩

- Anatoliy Timoschenko, USHMM, Oral History, 2005.595.29, File RG-50.575.0029, 32:51–33:06. For details, see: https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn44936. accessed 15.08.2022. ↩

- Kai Struve, Nimetska vlada, ukrainskyi natsionalizm, nasylstvo proty ievreiv: Lito 1941 roku v Zakhidnii Ukraini (Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2022), 550; Citation for Gabriel Finder, and Alexander Prusin, “Collaboration in Eastern Galicia: The Ukrainian police and the Holocaust,” East European Jewish Affairs, 34 (2004): 112. ↩