In an increasingly digital world, museums and archives have long incorporated the use of digital media technologies, applications, and resources to support research, exhibitions, and education initiatives. As a recipient of the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure’s Conny Kristel Fellowship, I spent four weeks at the Jewish Museum in Prague (JMP), a multi-building site spread across the Jewish Quarter of Prague, the historical origins of which date back to Prague’s first Jewish ghetto in the 13th century. The JMP’s numerous exhibitions span nearly a millennium of Czech Jewish history, and as I conducted my fellowship, I was struck by the fact that digital media applications were largely absent throughout the museum.

Originally opened in 1906, the JMP was taken over by the Nazis during the Occupation of Bohemia and Moravia, and nearly all of the items in its extensive collection—the largest of its kind—were stolen during World War II from Jews across today’s Czech Republic who were then deported to ghettos and camps, many of whom were murdered, their communities often destroyed thereafter.1 The JMP is unique not only for the provenance of its collection of Judaica, but also because of the museum’s unorthodox arrangement in a series of historic synagogues and ceremonial halls. Most of the museum spaces rely on traditional exhibition displays in glass plinths with short but informative text panels; yet, the simple displays are inherently heightened by their location within the beautiful synagogues, and in part, are intentionally understated in order to preserve the integrity of the spaces within which they are housed.2

The JMP’s few digital applications, which are present, are heavily concentrated in the Pinkas and Spanish Synagogues—the two museum spaces which engage with Holocaust history. While the objective to preserve architectural integrity extends to both the Pinkas and Spanish Synagogues, these spaces have nonetheless been equipped with digital technologies absent elsewhere in the JMP, reflecting broader turns towards the digital in Holocaust memory and representation. This article explores the use of digital technologies within the JMP as a case study for the museological memorialization of the Holocaust in the digital age, exploring the narrative demands of attempting to communicate the Holocaust—its precedents, implementation, and aftermath—and preserve the voice of survivors as we move towards a post-witness world.

The Pinkas Synagogue

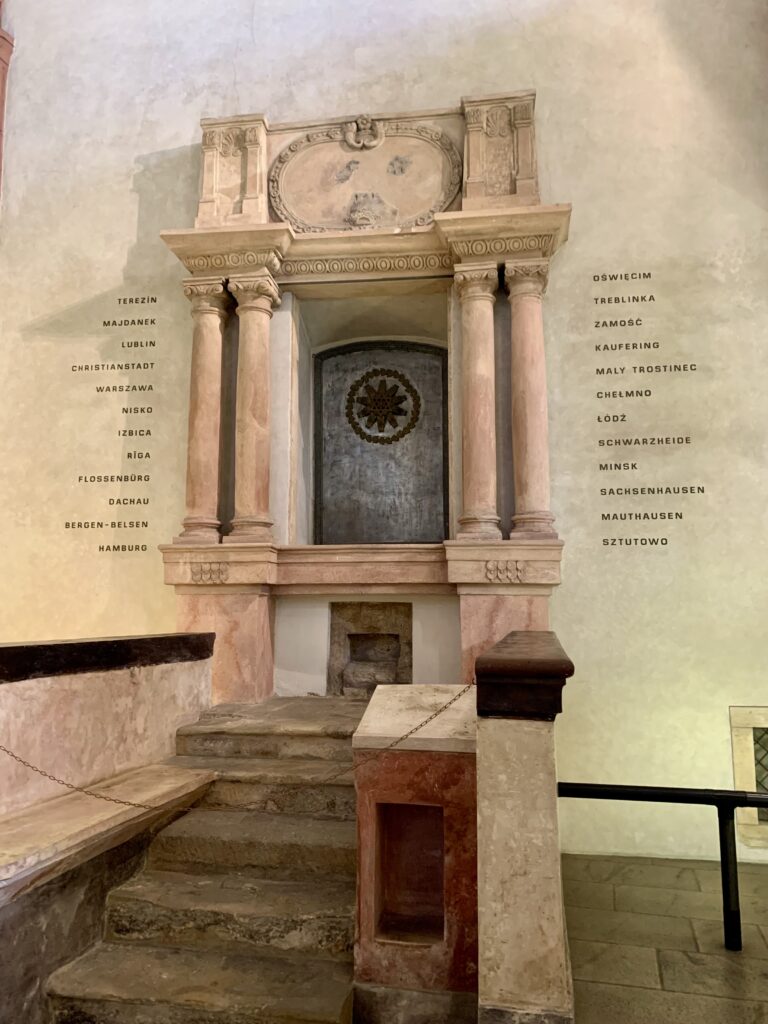

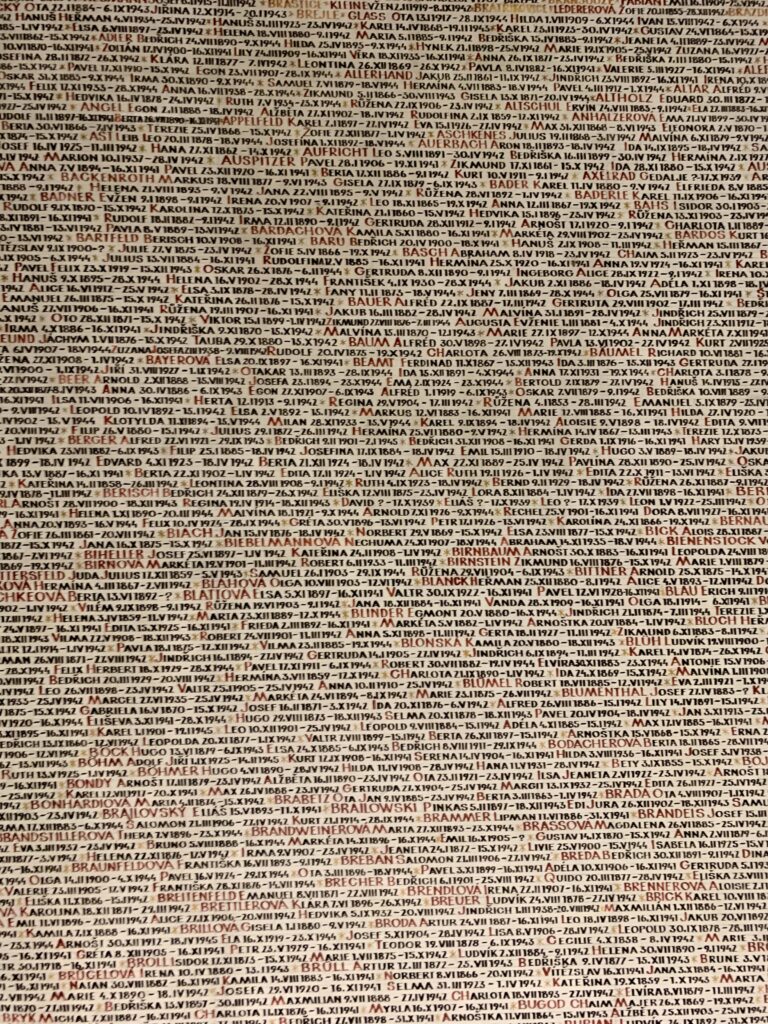

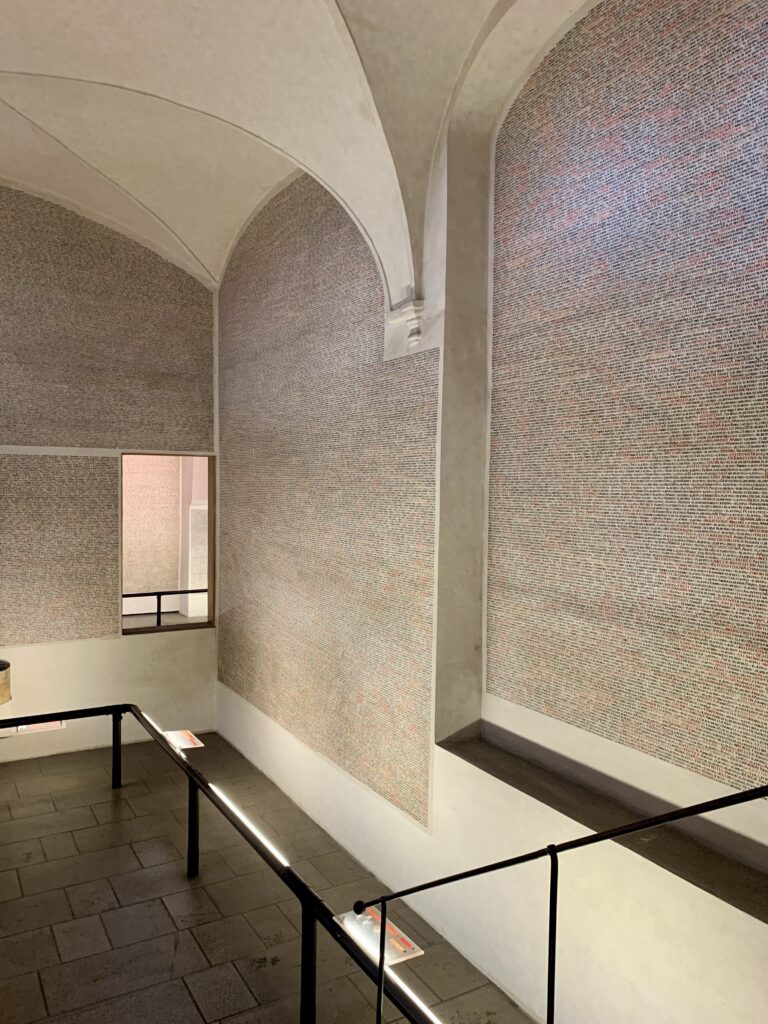

Built in 1535, the Pinkas Synagogue is the second oldest synagogue from the historic ghetto and is buttressed by the Old Jewish Cemetery, one of the most important sites in Prague’s Jewish community, which contains over 12,000 tombstones, the earliest of which dates back to the early 15th century.3 Today, the Pinkas Synagogue contains the JMP’s Memorial to the Victims of the Shoah from the Czech Lands. Designed and implemented in the 1950s, the memorial is one of the earliest of its kind with over 80,000 names inscribed on the interior walls of the synagogue.4 The names of the victims in the memorial are arranged according to the communities to which they belonged across Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia prior to their deportation to the ghettos and camps, and the list of names spans the vestibule, main nave, and women’s nave and gallery.5 The synagogue’s Holy Ark is also inscribed with the names of ghettos and camps where Czech Jews were transported and where many were murdered.6

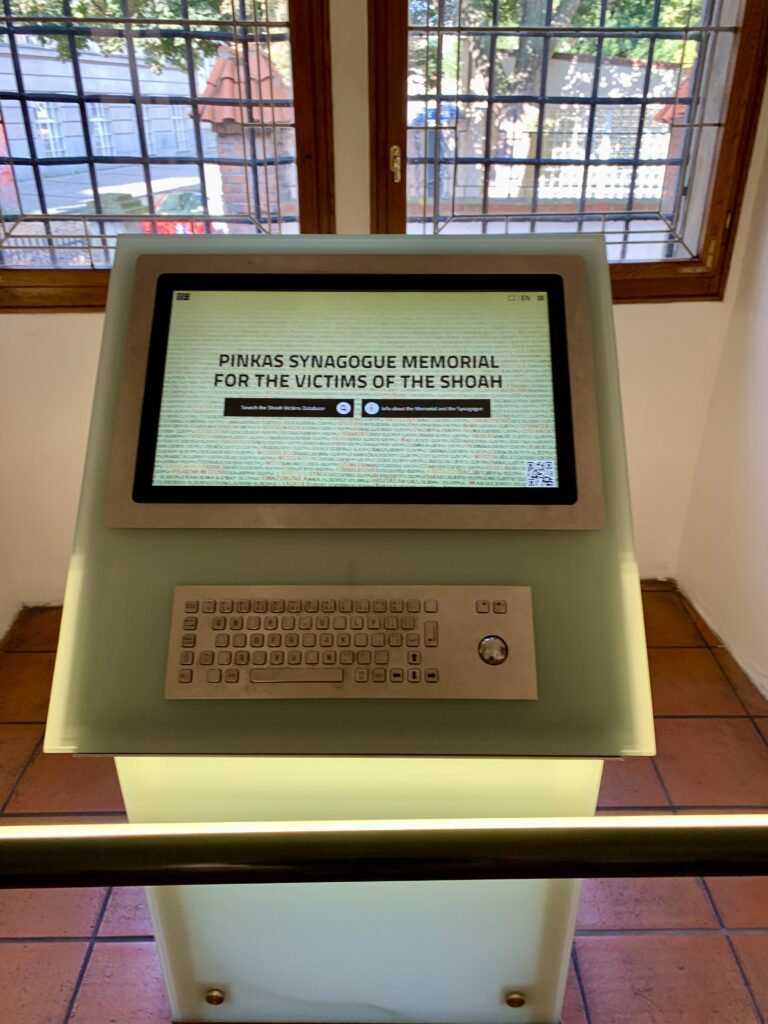

The names of these victims have been collected in a digital database, which visitors can access online or via an interactive kiosk from inside the synagogue. Visitors can search for victims by name and choose from a resulting list. The amount of information available about the victims—such as birth and death dates, any related digitized documents, etc.—varies based on the individual entry; however, all entries contain a navigation map, so that visitors might locate the victims’ names within the memorial. In addition to the database, the kiosk and website also provide a series of articles on the history of the Pinkas Synagogue, the memorial, and the temporary and permanent exhibitions, as well as a three-dimensional video tour. The accessibility of the database within the synagogue is intended to complement the visitor experience; not only does it afford visitors contextualization for the exhibitions which they are visiting, but it also allows them the opportunity to learn more about individual victims and to locate the history of the Nazi Occupation and the Holocaust within the Pinkas Synagogue’s—and by extension, the Jewish community of Prague’s—much longer history.

Moreover, the presence of the digital kiosk within the physical museum space indicates the popular turn in Holocaust memory and education in which technology is used to supplement the physical and archival. The kiosk—and the database and articles within—is a tool intended to be driven by the visitor for the purposes of his or her needs (e.g. learning more, finding a relative’s name, etc.). The focus, therein, is not on the victim, but rather on the visitor. This shift in focus reflects the critical move in the new millennium from what Holocaust historian Annette Wieviorka famously dubbed the “Era of the Witness” into what cultural historian Susan Hogervorst calls the “Era of the User”.7 Contemporary Holocaust media, such as relevant video games and social media, place increasing emphasis on user agency when it comes to engagement with the Holocaust, and this trend is being echoed in museology, wherein technologies are incorporated into the museum space in order to more critically engage the visitor. The Anne Frank House offers a virtual reality tour; Yad Vashem has the interactive IRemember Wall; the Museum of Tolerance, LA, has the Simon Wiesenthal Multi-Media Learning Center and the Social Lab; and museums such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Holocaust Galleries at the Imperial War Museum, London, and the Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne, have all employed interactive displays throughout their Holocaust exhibitions. Moreover, sites of terror, like the Dachau Concentration Camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, and the Bergen-Belsen Memorial are utilizing digital technologies, such as smartphone applications and virtual tours, to allow in-person visitors and online users a participatory, immersive, and interactive role. These efforts within the museum space are said to increase visitor engagement and access to the sites and often include digital tools for education.

However, there has been some debate “about the extent to which these phenomena activate critical and affective engagement, or interpellate the subject and encourage passivity”.8 Some critics have argued that visitor activity is not the same thing as visitor agency.9 Agency requires participation beyond scrolling through digital screens of content and clicking in or out of videos and articles. Traditional forms of visitor engagement with Holocaust history and testimony can include Q&A’s with historians or survivors, co-creation as in gaming, and pilgrimages to sites of terror—and it is the lack of agency offered by many digital installations which some argue inhibits true and affective engagement in the Holocaust museum. In taking a more critical approach to visitor agency, we may view the preservation, presentation, and (co-)creation of digital Holocaust memory as a collaborative process with the limits and possibilities of digital technologies as important as the curators’ and designers’ input and the users’ engagement. The articles and other digital media provided via the Pinkas Synagogue memorial kiosk, therefore, might not serve as a tool for effective engagement with visitors. However, the primary function of the kiosk is to act as a searchable database to navigate names within the memorial, and is, as noted above, intended to be driven by visitor interest and need. The kiosk then has the capacity to be both a tool for passive engagement and for visitor agency.

The Spanish Synagogue

Built on the site of the historic Old Shul in 1868, the Spanish Synagogue is so-called due to its lavish, Moorish style, designed after the Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain.10 The synagogue is richly gilt with elaborate ornamental features, carved wooden decorations, and stained-glass windows. After closing for religious services in 1941, the Spanish Synagogue was used as a warehouse for stolen Jewish property by the occupying Nazi forces.11 Currently, the Spanish Synagogue is home to the “Jews in the Bohemian Lands, 19th-20th Centuries” exhibition, which spans from the reformations of the late 1700s to the Velvet Revolution of 1989. The upstairs galleries focus on the Nazi Occupation of Prague, the Holocaust, World War II, and the post-war period, and it is here where the JMP’s application of digital resources and media feature most prominently.

The winter prayer room contains a series of large, rounded glass platforms with screens which play a continuous audio-visual presentation on Czech life from liberation in 1945 to the new millennium, and free-standing and hanging screens show looped archival photographs and film footage throughout the exhibition.12 One such screen features a slideshow which attempts to “convey the atmosphere and events of 1938–1945”, whereas another presents a different slideshow of photographs from the infamous Auschwitz Album, the only surviving visual evidence which details the mechanized process of mass murder at Auschwitz-Birkenau (digitized version available here).13 The JMP purchased glass-plate negatives of the album in 1947 from Lilly Jacob, who discovered the album in an abandoned SS barracks; Jacob used the money for the negatives to immigrate to the United States and eventually donated the original photo album to Vad Vashem.14

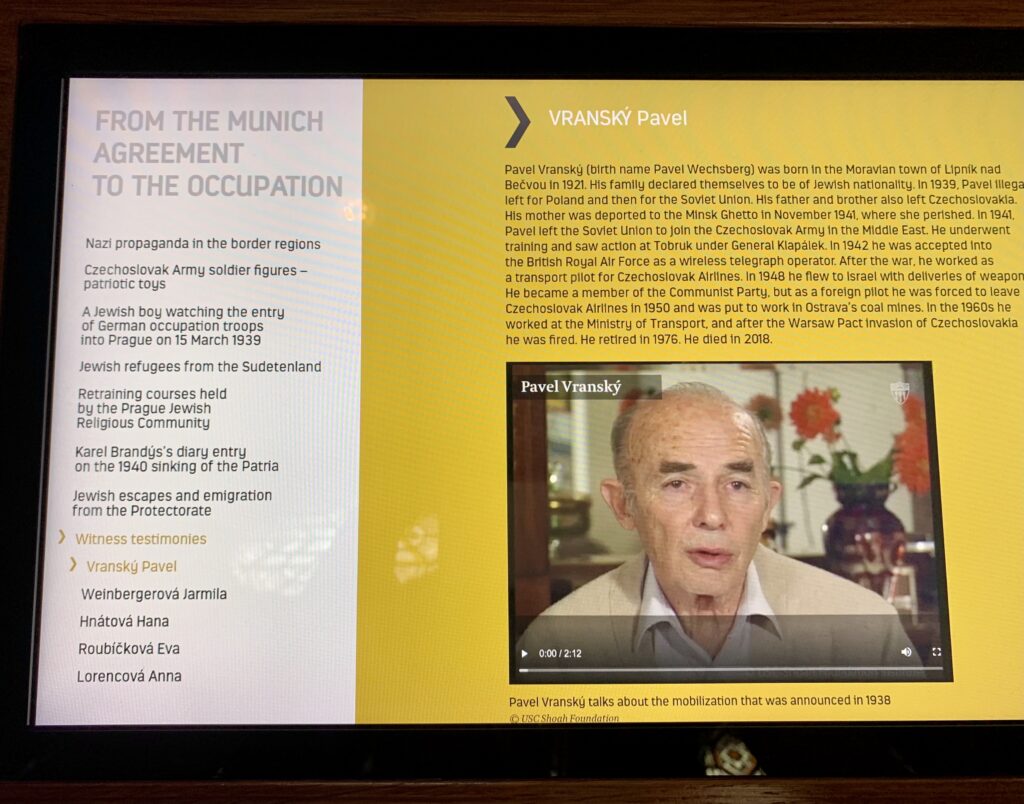

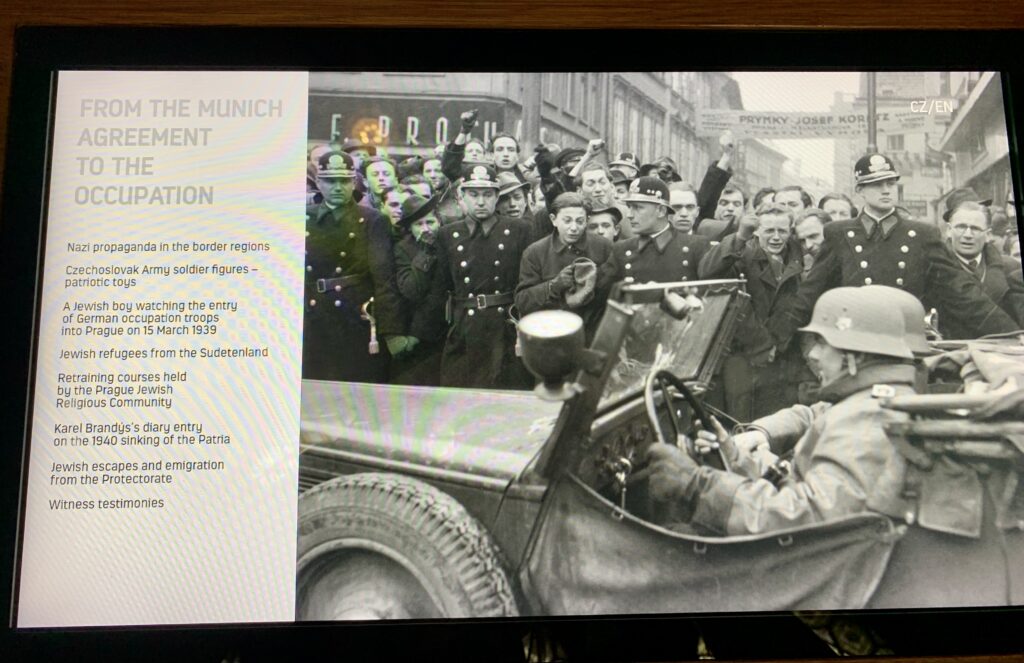

A series of wooden pews along the upstairs balcony of the Spanish Synagogue are equipped with touchscreens that allow visitors to engage with digital media, including digitized archival items and short articles, grouped thematically, which correspond to the surrounding exhibition. One such pew, titled “From the Munich Agreement to the Occupation”, displays a children’s scrapbook, photographs from a Jewish refugee camp in the Sudetenland, diary entries, and so forth. The pews are also equipped with headphones which allow visitors to interact with oral history testimonies from the Holocaust. The “Munich Agreement” pew includes the testimonies of Czech survivors Pavel Vranský and Anna Lorencová, among others. Vranský escaped the German occupation in 1939, fleeing first to Poland, then the Soviet Union, before he eventually joined the British RAF, working as a telegraph operator during the war. Lorencová was interred at Terezín concentration camp, along with her mother and siblings, and went on to work for the JMP, when it was under Communist State control. The presentation of Vranský’s and Lorencová’s testimonies alongside objects like the refugee photographs is intended to not only provide visitors with eyewitness accounts, but to contextualize and more wholistically convey the archival items, all while complementing the physical exhibition.

While many of the oral history testimonies come from the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive (VHA), the JMP’s own Shoah Documentation Department has contributed a number of testimonies to its Oral History Collection.15 The Department’s Jewish memory project, ongoing for nearly three decades, has recorded over 1,800 oral histories from survivors, as well as their descendants and relatives. The testimony archive is available to researchers in the JMP library, and as noted, a small sample of the collection can be accessed in the Spanish Synagogue’s exhibition.16

The importance of eyewitnesses in Holocaust memorialization and education well-known, and as we move towards a post-survivor age, many official Holocaust institutions are calling for contemporary generations to be secondhand witnesses to preserve Holocaust memory for future generations. The inclusion of survivor testimony within exhibitions has become common practice and signifies the modern phenomenon of digital witnessing. Museums, educators, and media content creators are turning to digital technologies to allow for the preservation, and often co-creation, of contemporary Holocaust witnessing and memorialization. Interactive oral testimonies, as with the USC Shoah Foundation’s IWitness program, provide digital touchpoints for Holocaust memory for those who otherwise will have little-to-no contact with survivors. Yet, while the interactive nature of the JMP’s oral testimony touchscreens provides visitors with an active role as they pursue what most interests them, the work is minimal and affords more performative action rather than authentic engagement. Moreover, some issues arise when survivor testimony is presented in pieces—the oral history testimony clips at the JMP are roughly two minutes or less—, often without context, and is then used to frame a specific narrative; in this case, to complement the archive objects on digital display and the greater exhibition setting. Nonetheless, it can be argued that it is better for the JMP’s visitors to have limited, curated access to survivor testimony than to have an absence of survivor voices throughout the Holocaust exhibitions.

HOLOCAUST.CZ PROJECT

Along with digital technologies in the museum spaces themselves, the JMP also has partnerships with sites like the Holocaust.cz project, which offers digital resources for visitors and the general public. Launched in 2001, the portal provides “a comprehensive history of Nazi racial persecution and genocide with a focus on the territory of today’s Czech Republic”. 17 The purpose of the project is to locate this period of Czech history within the broader historical and European context with a focus on those persecuted by Nazi racial policy, including Jews, Roma, and Sinti, through the use of personal stories.18 The website includes a victims database created by the Terezín Initiative Institute, the Terezín Memorial and the JMP, along with a digitized documents database and a variety of articles on the history and terminology of the Holocaust in the Czech Republic. Such databases offer a more critical form of testimony witnessing, wherein users are able to encounter multiple testimonies which can both support and contradict each other, providing at once both more nuanced and more holistic narratives of the Holocaust. Though such databases are becoming increasingly more popular—both for scholarly research and for public use—, some debate has arisen regarding the dangers of searchable survivor databases. Scholars like Hogervorst acknowledge that allowing users to search and compare different testimonies can obscure “the focus on emotional identification and empathy as has become ubiquitous in oral history and Holocaust education”.19 But as we move towards a reality in which eyewitness accounts are only available in mediated forms, publicly searchable databases—much like oral testimony archives—will likely become the standard as Holocaust institutions continue their efforts to preserve and honor the lives and voices of survivors.

CONCLUSION

A sprawling museum which encompasses the Czech Republic’s oldest surviving Jewish neighborhood and whose exhibitions span centuries of Czech Jewish life, the Jewish Museum in Prague offers a unique perspective on the Holocaust and museum culture. A largely traditional museum, the entirety of the JMP’s digital applications are located in the two spaces which feature the Holocaust as a result of emerging trends in Holocaust memory and representation in the “Era of the User”. The digital resources and applications explored above provide the JMP’s visitors, both in-person and online, with a connection to the stories of survivors, such as Vranský and Lorencová, and a touchpoint for everyday objects of the past. While some debate remains regarding the truly affective nature of the digital installations, these virtual materials nevertheless evidence efforts towards accommodating a visitorship which is becoming increasingly more technology-literate and media-focused. As technology advances, the museum space will continue to reflect these changes alongside the evolution of Holocaust memory and memorialization in the digital age.

- Leo Pavlát, “The Jewish Museum in Prague during the Second World War”, European Judaism 41(1) Mar 2008: 124. DOI:10.3167/ej.2008.410115; “Old Jewish Cemetery”, The Jewish Museum in Prague (2023), https://www.jewishmuseum.cz/en/explore/sites/old-jewish-cemetery/ ↩

- Michaela Sidenberg, Iveta Cermanová, and Jana Šplíchalová, “Jews in the Bohemian Lands, 19th–20th Centuries: New Permanent Exhibition of the Jewish Museum in Prague at the Spanish Synagogue”, Judaica Bohemiae 1 2021: 95. ↩

- Arno Pařík, Jewish Prague, 5th Ed, Trans. by Stephen Hattersley, The Jewish Museum Prague (2007), 10. ↩

- Pařík, 11; “Pinkas Synagogue”, The Jewish Museum in Prague (2023), https://www.jewishmuseum.cz/en/explore/sites/pinkas-synagogue/ ↩

- Pařík, 11; “Pinkas Synagogue”. ↩

- “Pinkas Synagogue”. ↩

- Annette Wieviorka, The Era of the Witness, trans. by Jared Stark, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006; Susan Hogervorst, “The Era of the User: Testimonies in the Digital Age”, Rethinking History 24 (2), 2020: 169-183. ↩

- Victoria Walden, “Afterword: Digital Holocaust Memory Futures: Through Paradigms of Immersion and Interactivity and Beyond”, in Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research, ed. Victoria Walden. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021, 269. ↩

- See Janet H. Murray, Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018; Anna Reading, “Digital Interactivity in Public Memory Institutions: The Uses of New Technologies in Holocaust Museums” Media, Culture, and Society 25, 2003: 67-85. ↩

- Pařík, 30; “Spanish Synagogue”, The Jewish Museum in Prague (2023), https://www.jewishmuseum.cz/en/explore/sites/spanish-synagogue/ ↩

- Pařík, 31. ↩

- Sidenberg, Cermanová, & Šplíchalová, 97. ↩

- Sidenberg, Cermanová, & Šplíchalová, 110. ↩

- Sidenberg, Cermanová, & Šplíchalová, 110; “Lilly Jacob”, Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center (2023), https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/album_auschwitz/lili-jacob.asp. ↩

- Jana Šplíchalová, “The Stories behind New Acquisitions in the Collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague”, Judaica Bohemiae 2, 2022: 97; Sidenberg, Cermanová, & Šplíchalová, 100. ↩

- Šplíchalová, 97. ↩

- “Information about the Holocaust.CZ Project”, Holocaust.cz, Dec 2021, https://www.holocaust.cz/informace-o-projektu-holocaust-cz/. ↩

- “Information about the Holocaust.CZ Project”. ↩

- Hogervorst, 176. ↩