On February 16, 1947, Pinus Rubinstein a Holocaust survivor from Cernăuți (Ukr. Chernivtsi), then living in Romania, was preparing to leave for Palestine. He wrote in his diary:

Today is probably the hardest day of my life. Put my files and documents in order. With a bleeding heart, I must sacrifice and destroy dear, expensive books, files, documents, and important letters that have been my pride and joy all my life—as if they were living friends that I am sacrificing to death. Who can understand my pain? However, it had to happen—and it did happen—for the sake of my children.

These lines might seem rather surprising when read today. By 1947, Pinus Rubinstein, who survived the Holocaust in Cernăuți, had gone through a series of hardships and ordeals: consecutive antisemitic regimes, successive military invasions and occupations, ghettoization, the threat of deportation, bombardments, and displacement from his hometown and native region. And yet, in spite of this, he chose to describe this winter day, almost two years after the end of the war and almost three years after his “liberation” by the Soviets, as “probably the hardest” of his life.

The history of the Holocaust in Romania and in Cernăuți, and what Rubinstein experienced in the years leading up to this moment in 1947 are all but unknown.1 But this post sets out to explore through Rubinstein’s diary what we might call the “lived experience” of this period. Lived experience can be understood as a self-conscious historiographical approach.2 And while such an approach can be applied to other kinds of documents, for this purpose, diaries constitute a privileged source. Indeed, diaries are less about what happened and more about how what happened was processed subjectively. As such, they require a specific kind of reading and interpretation: The document’s form, for example, is almost as important as its content; the silences are as telling as the statements. But they thereby also make it possible to explore and trace beliefs, emotions, and social responses through time – to create what Amy Simon has called “a taxonomy of perception.”3 And when it comes to Holocaust research, this has proved especially fruitful.4

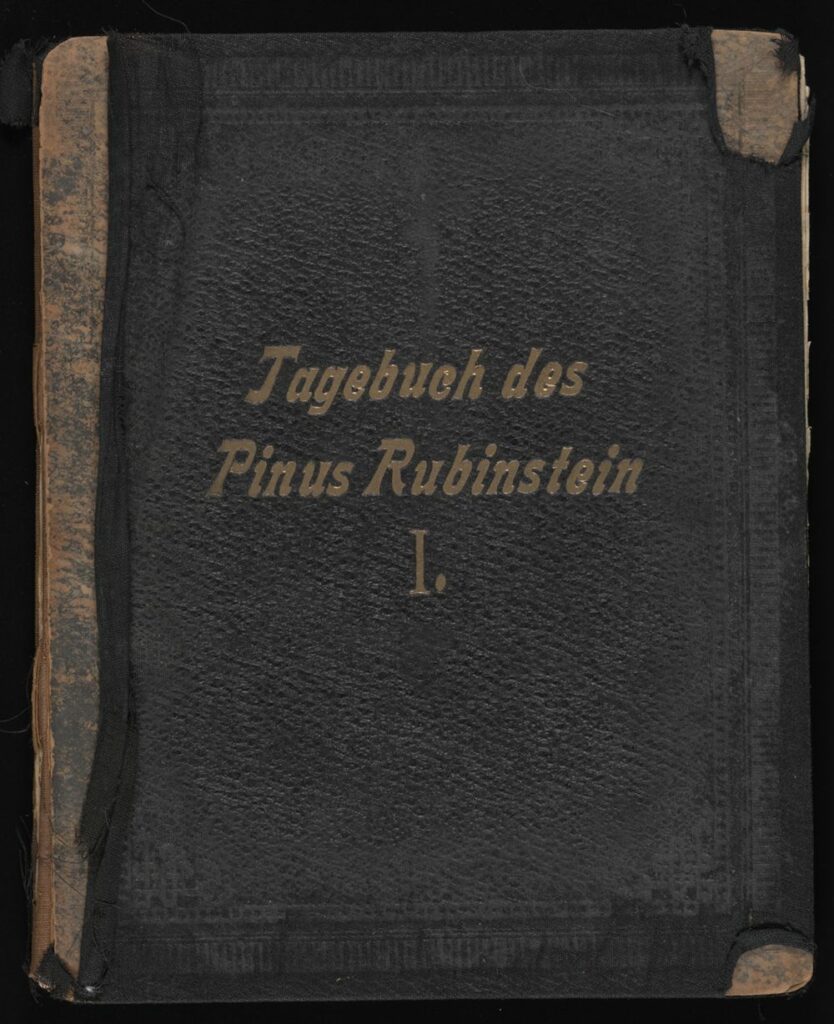

With this in mind, the diary of Pinus Rubinstein (1888–1963) constitutes a unique resource. Rubinstein, a barber who lived in the city of Cernăuți with his wife Peppi and two sons, Edi (Eduard) born 1916 and Bubi (Mordechai) born 1918), kept a diary for almost five decades, from 1900 to 1949—most of his adult life—including throughout the war and the Holocaust.5 The three handwritten notebooks, amounting to hundreds of pages, survived the years of persecution as well as Rubinstein’s emigration and are now held by the USHMM and have been fully digitized.6 While I focus below on the third booklet and the period of the Holocaust, the availability of the earlier sections makes possible a deeper contextualization and interpretation of the years of persecution, and these would also be worthy of further exploration. The language of the original diaries is German. All translations are my own.

Jewish Life in Interwar Cernăuți: An Ambivalent Experience

The years between the wars were an ambivalent time for Jews in Cernăuți. On the one hand, Cernăuți, at the time the second largest city in Romania, was very much a Jewish city and an exciting place to be.7 On the other, antisemitism had been a longstanding feature of Romanian political life, and, particularly in the country’s newly acquired borderlands such as Bukovina, efforts to “Romanize” always went hand in hand with antisemitic discrimination.8 Historians have pointed to various turning points in the history of Romania’s right-wing radicalization after World War I. Yet looking at how people at the time experienced and interpreted events can help complete the picture.

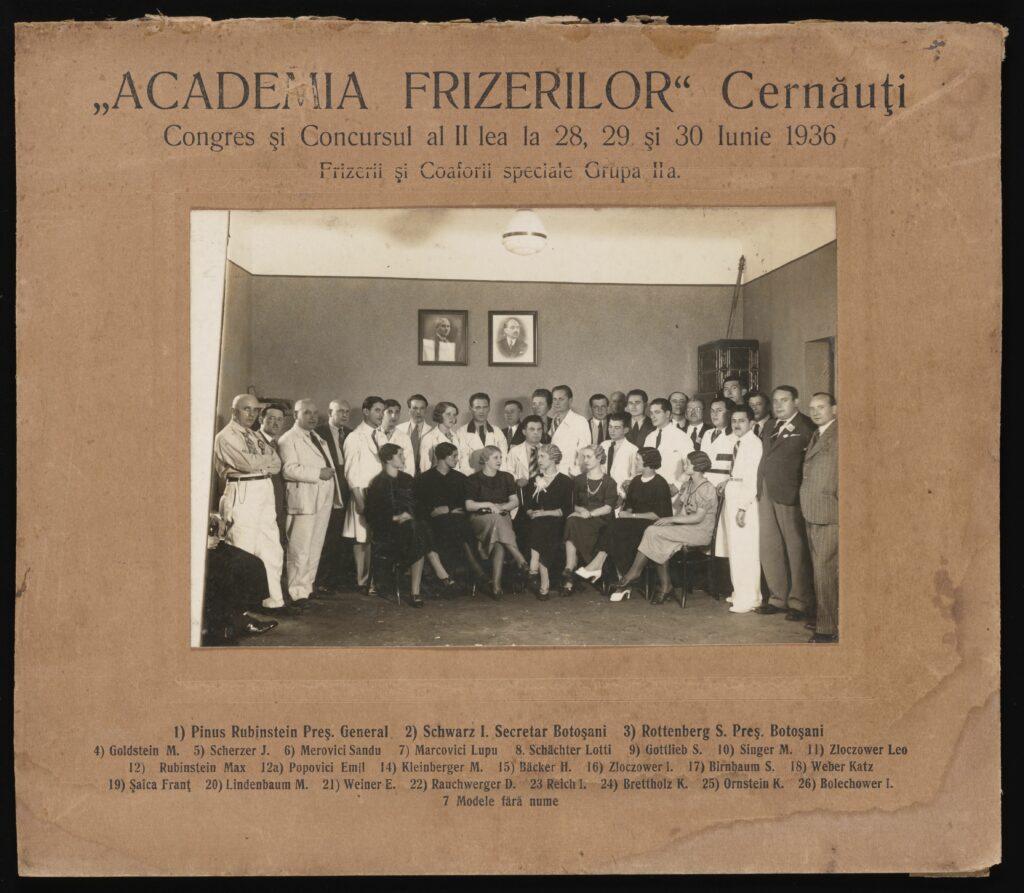

For Rubinstein, in the first years after the end of World War I, life seems to have gone on with rather common ups and downs. Though he did experience some financial problems in the early 1920s and occasionally cursed the country’s politics,9 he also described enjoying life more as he aged and achieved a great deal professionally. He not only had his own business but headed several charitable and professional organizations, including the city’s Hairdressers’ Academy of which he was the founder and long-term president.

Rubinstein’s first longer mention of politics and personal struggles in the diary dates from late 1930. By then, the worsening economic situation, inflation, and the deteriorating political climate in Romania were impacting his life significantly. On December 12, 1930, he noted that he would like to live less far away from his shop because he no longer felt safe in the evenings when walking home. In the next entry, dated January 24, 1931, he noted that for the first time since they married 16 years earlier, his wife had to work—something he regarded as embarrassing.

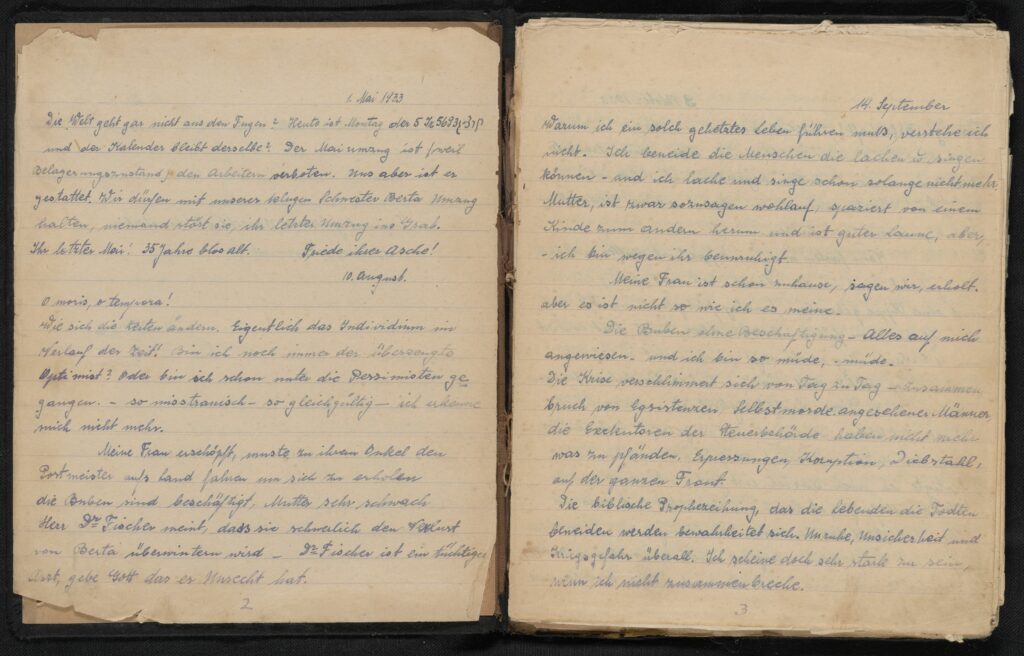

This marked the onset of a difficult few years. On July 15, 1931, he commented on the consequences of the global economic crisis, which had hit Romania with some delay, but especially hard. The situation was causing huge distress and an “epidemic of suicides.” Two years later, in 1933, the situation had still not improved, and it was wearing him down. On September 14, 1933, he wrote:

The boys [his sons] without work. Everyone depends on me, and I am so tired, tired. The crisis worsens day by day. The destruction of livelihoods [,] suicides of respected men[,] there is nothing for the bailiffs of the tax authority to seize. Extortions, corruption, theft, across the board. The biblical prophecy that the living will envy the dead is coming true. Unrest, insecurity, and the threat of war everywhere. I must be very strong after all, to not break down.

The diary does not mention the election of Hitler in Germany in January 1933. That year, Rubinstein’s sister got sick and both she and Rubinstein’s mother later passed away, so he had other things on his mind. But the entries from this time nevertheless capture a growing pessimism, which contrasts sharply with his earlier hopefulness.

The Goga-Cuza Government: A Watershed Moment

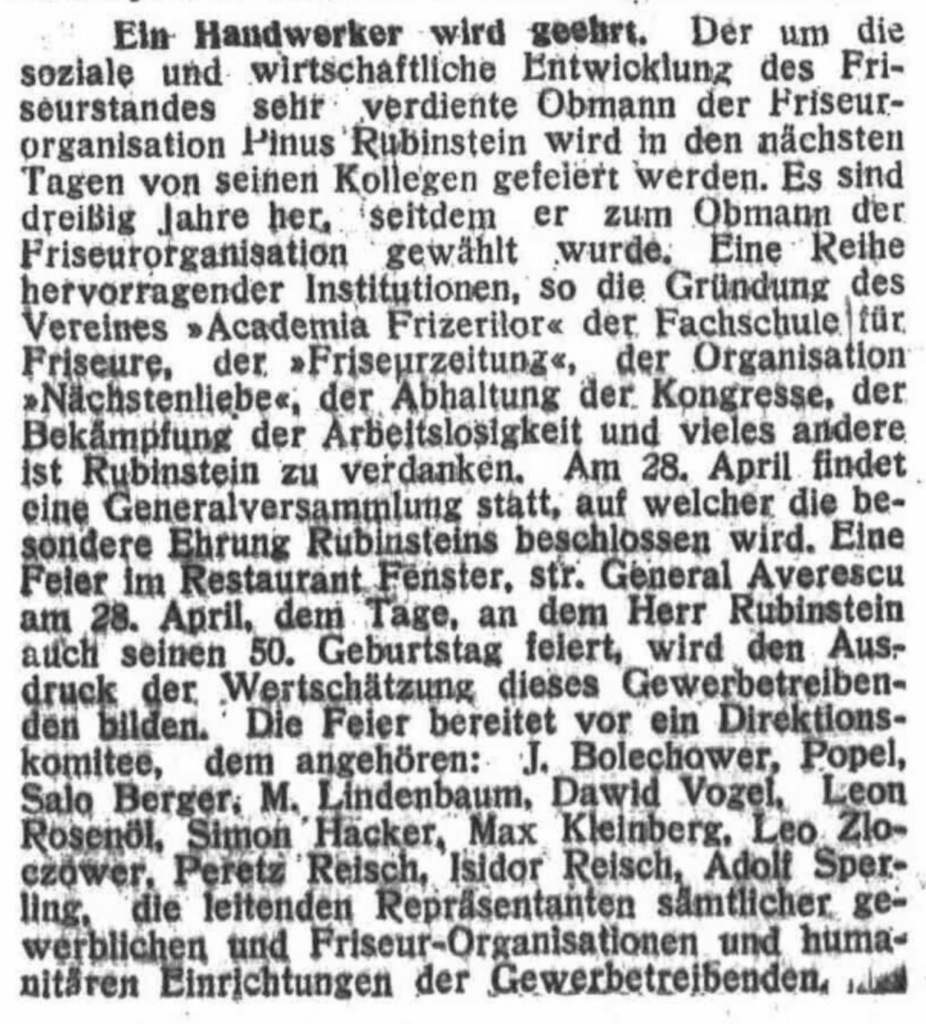

In the medium term, the situation did improve. The late 1930s saw a number of personal and professional successes for Rubinstein. In July 1936 he received “the commercial and industrial order of merit”; in December 1936, his elder son—also a barber—opened a small shop in the village of Molodia (Ukr. Molodyia); and in 1937, Rubinstein was named for two years in the local “Chamber of Employment.” When he turned 50 in April 1938, a celebration was organized to honor him and his contribution to the hairdressing profession in the city in particular, and mentioned in the Czernowitzer Allgemeine Zeitung, one of the city’s major dailies.10

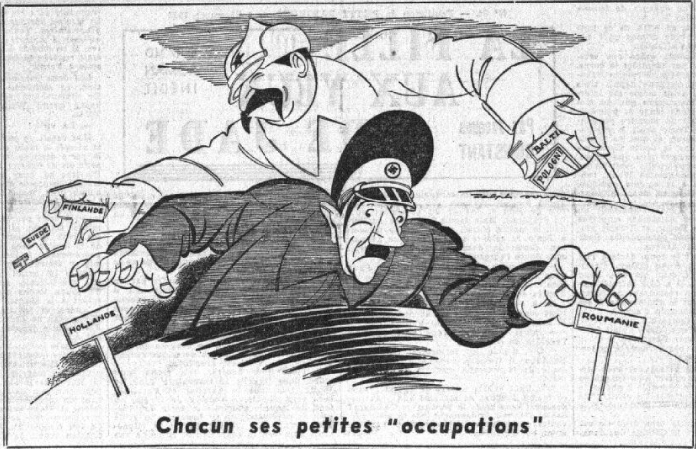

But the election of December 1937 and the subsequent appointment of a cabinet led by two notorious antisemites, Octavian Goga and Alexandru C. Cuza, constituted a turning point for Rubinstein and for Jews in Romania in general. Although this government lasted just under two months, the king subsequently abolished parliament and installed a dictatorship. What is more, the “revision of the citizenship” of the country’s Jews, called for by the Goga-Cuza government was maintained under the new regime. As such, December 1937 marked the end of democracy in Romania and the beginning of state-led antisemitism.11

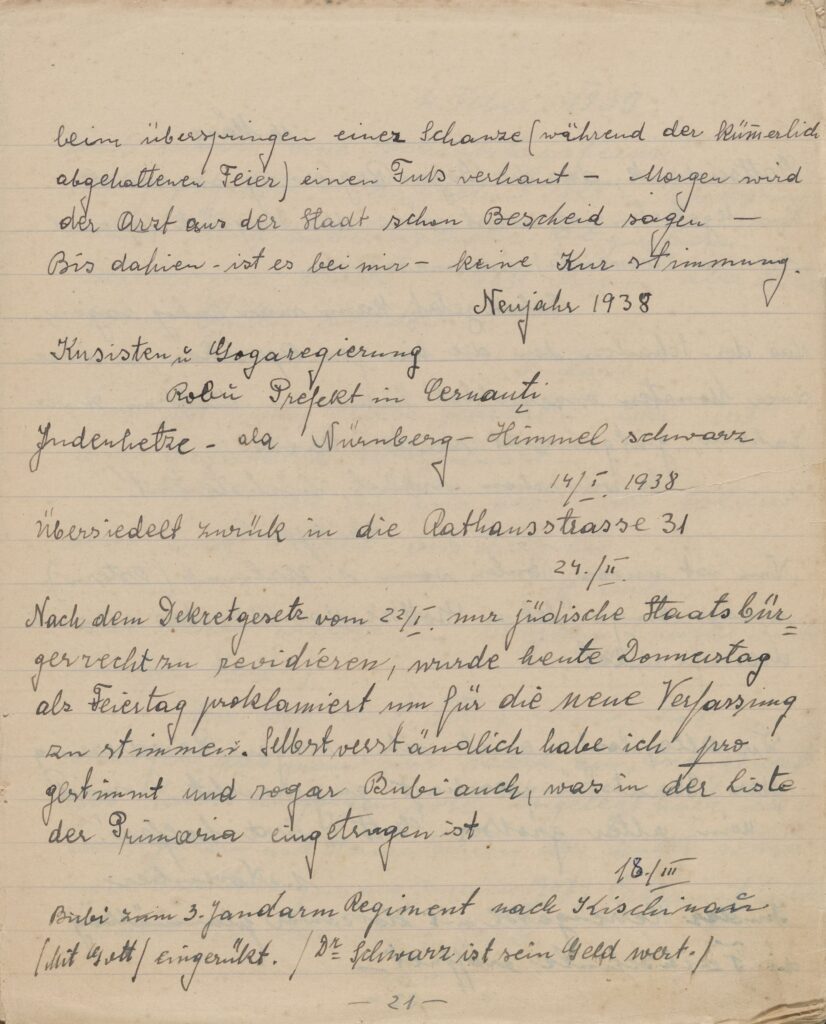

On January 1, 1938, a few days after the election, Rubinstein expressed his horror and disbelief in a concise manner.

“New Year 1938. Cuzists12 and Goga government. Robu13 Prefect in Cernăuți. Jew-baiting à la Nuremberg—black sky.”

A few weeks later, after the government’s fall, he endorsed the king’s new regime with his vote and expressed his relief. However, Rubinstein was one of those whose right to citizenship was to be reevaluated. Since his father had died young, Rubinstein lacked evidence of his birthright from the Austrian period, and this could potentially lead to his becoming stateless, with implications for his children as well.

In the diary, the entries relating to this issue stretch over many months, from early 1938 to mid-1939 and show how exasperating and unnerving the situation was. On April 22, 1938, he wrote about submitting a file concerning the revision of his citizenship. Over a year later, on July 18, 1939, the process was still not complete:

The lawyer Mr. Steigmann has helped me to quickly obtain an “Indigenat”14 from my father. I enclosed: my marriage certificate and my mother’s certificate of origin [Heimatschein] as well as my work certificate from Bojan (1907).

Ten days later, on July 28, 1939, after his wife and son went on holiday without him so he could take care of the matter, he wrote that the court in section 30 had approved his papers and written “admis”15 on them. However, there was still a further step.

Finally, on August 18, 1939, he noted:

God lives! Today at 11am Mr. Vlad, the public prosecutor, approved in the court of last resort the Ostaficzuk verdict of July 28, thus definitely recognizing my citizenship and freeing me from this terrible nightmare. Thank God.

The repeated and emotional entries convey Rubinstein’s relief at the positive outcome. Yet the frequent references to God and mention of the bureaucratic minutiae highlight his sense that this was not about justice, due process, or the rule of law but rather fate, fortune, and administrative despotism. He certainly did not forget this experience, and it altered his image of the state and his relationship to it. When, a few months later, on November 22, 1939, both his sons were forced to enlist in the Romanian military, he pointed out the irony:

I do want it to be an honor for me that both children fulfill their duty to the fatherland at the same time—but something’s not right!! The minorities are not recognized as full citizens. It’s a joke. . . . Now Edi has also been called up! And [we are] now alone again!

The “Russian Year” 1940–1941: The Terror before the Storm

Although World War II broke out in September 1939 and its consequences could be felt in Bukovina from the outset, the invasion of the northern half of the region by Soviet troops in the summer of 1940 constituted a major escalation. This marked the start of a one-year occupation of the city, from June 1940 to June 1941, which has become known among many survivors from the region as the “Russian year”.16 A great deal changed overnight: society and the economy were re-organized according to radically new ideological principles; Russian and Yiddish replaced Romanian. Many people (ethnic Romanians and ethnic Germans) fled the region; others arrived. While some were afraid, others celebrated.

In his diary, Rubinstein did not discuss this period at great length. But he was definitely very concerned about what was happening. On June 1, 1940, for example, he noted briefly:

Am worried—there is talk of Northern Bukovina being ceded to the Soviets, without a plebiscite. I cannot understand this.

The next entry, on June 28, 1940, read:

Now it is true! Today the Soviets moved in. So much military, [so many] tanks, machines, and the like, that I can’t even keep count. The population’s welcome was enthusiastic—flowers were strewn like carpets, loud joy that is difficult to describe right now.

As for me, I haven’t got round to thinking about what I should make of it, because both my sons are in the Romanian army, and we are here alone.

A month later he noted with relief that his sons had come home, and in the period that followed he seems to have just kept going—working in a salon and providing for his family. But it is notable that he wrote very little during this period.

In March 1941, he noted that his elder son had decided to get married. Rubinstein was not happy about it. He himself had thought long and hard about whether he should marry and thought his son’s decision was precipitated. But as others have noted, many young people got married in this period, feeling they had nothing to lose, and this can be considered symptomatic of how members of different generations responded to this time of uncertainty.17

The very next entry was from the summer of 1941 and testifies to the panic and chaos that accompanied the end of the “Russian year.” During this phase, Rubinstein wrote almost daily.

On June 16, 1941:

It’s frightening! Countless citizens, among them S. Haker, were sent away because they were allegedly loyal to Romania or wealthy. There are informers everywhere. . . . Young people are secretly being concentrated; there is talk of war with Germany and Romania.

Six days later, on June 22, he wrote again:

I am stunned. Since the 20th, young people have been sent away en masse. They are working so secretively and feverishly on the defense of the city. Russian women and children are being evacuated. I myself saw a German airman today—but this is being kept absolutely quiet.

Two days later his children were drafted once again into the military, and he feared he would never see them again. Two days after that, he noted that the bombings had eased. Then, on July 3, the Soviets started leaving the city. Many fled, others were, as he says, “forcibly taken”;18 everything was “in motion.”

The next day, on July 4, he commented that the power vacuum created by the Soviets’ departure had led to chaos, violence, and destruction—buildings were being looted, blown up, and set on fire. He also noted the ease with which many had switched sides and feared that it would all eventually “be blamed on the Jews.” He concluded with the prayer: “May God protect us.”

His sobering note on July 5, 1941, gives a unique insight into the sense of expectation, fear, and helplessness at this decisive moment of transition between Soviet and Romanian rule over the area:

No Russian and no communist in Czernowitz.19 And the informers are making themselves scarce. Now others are replacing them. Just a burning city and looted stores.

Many of those who only yesterday carried out the work of destruction with the Russians, today already brandish swastika flags, flowers, cheer hurrah, and bow down to the Romanian patrols.

The soldiers arrive in small groups—the 14th Dorobanti20 have been raging terribly among the Jews. It is a struggle for me to write down the facts. Unfortunately, the wild rumors of Jewish pogroms are proving true. May God protect us all.

German-Romanian Reoccupation: The Onset of Mass Murder

In many postwar Jewish memoirs the “Russian year” is remembered as a dire and frightening time. But with the reoccupation of the region by German and Romanian troops in July 1941, worse was in store. The Germans stayed only a few weeks in the city, but they carried out arrests and mass shootings, destroyed buildings including the city’s great temple, and famously set up an office in one of the city’s hotels, the Hotel zum Schwarzen Adler.

In the early days of the invasion, it was difficult to get an overview of what was going on. Fear and confusion were widespread and even in the writings of historians, accounts of what happened vary quite widely.21

According to his diary, Rubinstein initially remained hidden at home. He seems to have found out about the arrests and disappearances through acquaintances – presumably non-Jews – who dropped by and brought over food.22 However, their mood was somber, too. He described one of them as “unsettlingly quiet” and “unwilling to say a word”.23

His situation improved somewhat in the following weeks as calm was restored. At the end of July, his son Edi came home with a prisoner transport and was able to go home; three weeks later, Bubi who had been made prisoner by the Germans but managed to pass as ethnic German was set free, too. Nonetheless, a sense of danger remained omnipresent. On August 4, Rubinstein had noted that “all Jews of all ages and sexes” had been ordered to wear the yellow star. After this, his entries became sparser once more. Whether and if he found out about the crimes that were being committed in the surrounding towns and villages and neighboring region of Bessarabia is not known.

His next entry is dated October 11, 1941, an infamous date in the history of the Holocaust in Cernăuți. That day, the city’s entire Jewish population was forced into a ghetto of just a few streets in preparation for their deportation further east. After weeks of silence, it seems as if a surge of emotions compelled him to write.24 The words are pouring out revealing his shock and anger:

That was one of the most incredible of days! Without any warning and without any prior agreement, “All Jews,” about 60,00025 people from Czernowitz, were shoved into the Jewish quarter in a rush that can hardly be imagined.

By 6 o’clock in the evening it was over, period! So many tears—so much damage—apartments locked and abandoned. We only took backpacks and bare necessities. An interesting and sad relocation of innocently condemned masses, a swarm of desperate people coming from all directions, it seems as though the streets and the houses are also moving along and crying.

Two transports of Jews have been deported to an unknown area (Transnistria).26 SS men officiate for a short time, politely and confidently. The Romanian military is on guard duty. The police are nowhere to be seen.

I and my loved ones live in the apartment of the painter Krinitz, Grabengasse 2b. Whether the ghetto will remain permanently is uncertain. The streets around the ghetto are boarded up, and the Jews look out as if from a chicken coop. Former homeowners—intellectuals—camp out at night in the filthiest of courtyards under the open sky.

Such horror exceeds the limits of the imagination.

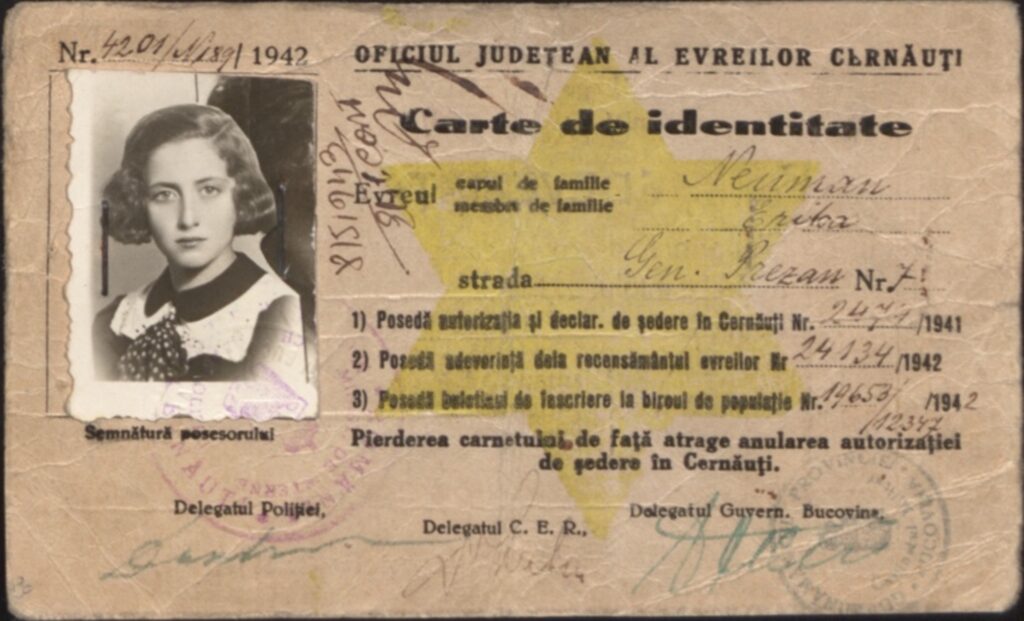

In the end, the Cernăuți Ghetto only existed for a few weeks, but not all Jews were deported from the city. Concern about what this would mean for the city’s economy resulted in about 20,000 being given authorizations and permitted to go home.27

Rubinstein and his family belonged to this minority of people who were able to remain in Cernăuți. On October 27, more than two weeks after the establishment of the ghetto, he wrote succinctly about this new development:

They say specialists will be allowed to work in the city. The uncertainty is terrible. Money is exchanged for rubles, suits are being gifted, cloth ends and pillows are sold for 200 l[ei] – immeasurable wealth is being destroyed.

We now have an authorization to go home. Anyone who [has] felt this anguish can appreciate this joy! People, who had been sentenced to death, suddenly pardoned.

Jewish Life in Cernăuți 1942–1944: Like Living on an Island

The situation in Cernăuți between 1942 and 1944 was rather exceptional. If living conditions were harsher here than in the so-called old kingdom of Romania, they were also unquestionably better than under German occupation across the border in occupied Poland and Ukraine, just a few kilometers away. As the famous Zionist from Bukovina, Mayer Ebner, then in Palestine, noted in a letter to American Jewish leaders in 1943, the Jews in Cernăuți were living “as though on an island.”28 Aspects of normal life persisted alongside innumerable restrictions, persecutions, and the constant fear of losing one’s authorization or being arrested and deported after all.29

Again, Rubinstein wrote little during this period. His last entry from 1941 mentioned briefly and factually that he and his sons had started working with others in two different barber shops and that there was a lot of work. But his next entry, on New Year’s Day 1942, a date on which he traditionally always noted something down, was a desperate lament:

Would all the water in the world be enough (if it were ink) to write down the sufferings of the Jewish people?

So godforsaken, so helpless—one speaks again of deportations—God willing it shall not come to that—enough shot, frozen and starved, enough. Where did these hyenas learn this way of treating people so barbarically?

Barbarians! Where have the people disappeared to?

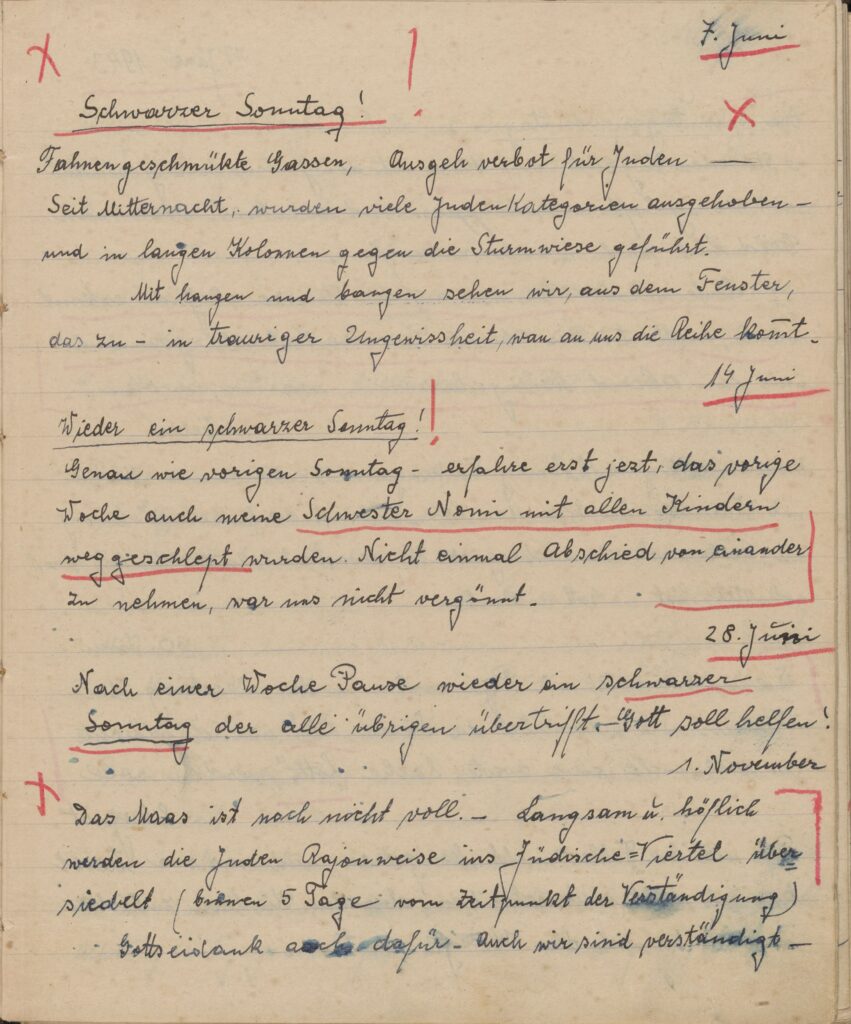

After this, he did not write again for another six months, not until another fateful day in the history of the Holocaust in Cernăuți. That day was the start of the second wave of deportations from the city in spring 1942, which took place on several consecutive weekends.30

At this point, Rubinstein’s shock, anger, and despair were immense. Three times in a row, on June 7, 14, and 28, he started his entry with the underlined heading “Black Sunday!” On June 7, he remarked that they had “look[ed| out of the window with fear and trembling—in sad uncertainty as to when it w[ould] be [their] turn.” A week later, on June 14, Rubinstein found out that his sister, Nomi, and her children had been taken away the week before, and he noted that they did not even get a chance to say goodbye. On the last Sunday, June 28, he wrote with emphasis: “After a week’s break, another black Sunday that surpasses all others. May God help.”

These events raised concern and outrage among many Jews inside and outside Romania and even among some non-Jews in Bucharest and elsewhere. They were to be the last mass deportations from Cernăuți, but of course Rubinstein could not know this, and the diary shows how his anxiety persisted for a long time afterward. It was triggered by incidents such as brief arrests, expulsions of Jews from their apartments, new restrictions, and rumors. At the time, the sense of danger was pervasive and there was no way of knowing what was a real threat and what was not.

In 1943, the social and political situation of Jews in Cernăuți began to improve slightly. Life also seems to have become somewhat better for Rubinstein. The family got a new and cheaper apartment; his son Bubi also decided to marry. In general, at this time, his preoccupations and tone appear to have been less grave.

However, living under extreme conditions by no means guarantees harmonious interpersonal relations. In fact, challenges to traditional gender roles and existing (often patriarchal) orders often place a strain on families.31 Again, Rubinstein’s diary bears this out. While he opposed his younger son’s marriage plans, his wife Peppi supported them. He felt very disappointed by this. Confiding in his diary on November 9, 1943, he noted he felt isolated, “like a stranger among his loved ones.”

With the possibility of the province’s evacuation drawing ever closer, however, he also realized they had other concerns. And on January 2, 1944, when his son’s wedding was finally celebrated, he wrote down: “So be it. May God grant him happiness.”

The End That Wasn’t the End: A Continuum of Suffering

As the war and the Holocaust came to an end in Cernăuți the situation was again extremely confusing and frightening. The withdrawal of the German troops greatly worried the Jewish population. People were afraid of reprisals and, indeed, persecution measures were not lifted all at once. Rubinstein’s son Bubi was for instance sent to Romania for forced labor at the end of March 1944, although the withdrawal of the German-Romanian troops was imminent. Just one day later, on March 26, 1944, Rubinstein wrote:

That was an incredible night!

Factories and other houses are being blown up continuously. The sky is continuously colored red, and green flashes momentarily make the sky as bright as day. Everyone has hidden in shelters, only I stay behind gladly as a guard.

. . . The arrival of the Red Army is imminent.

Two days later, the Red Army entered the city.

The period that followed constitutes a completely new chapter that exceeds the scope of this post. But it is nevertheless interesting to mention that although Rubinstein initially welcomed the Soviets, approached the new regime with goodwill, and tried to make a new start,32 this period brought with it many disappointments and hardships of its own. For one, it was when many survivors took stock and realized what had happened during the war. For another, even though the circumstances were radically different, at times, it was impossible not to see and draw parallels to the preceding regime of persecution. On May 1, 1944, for example, Rubinstein noted with dismay that men between 18 and 50 years old were being sent away “much like in June 1941.” Bubi had still not returned from Romanian forced labor, and now he feared his elder son Edi would be taken away, too and that he and Peppi would be alone again.

A month later, on June 7, 1944, Edi was indeed stopped on his way to work. His head was shaved, and he was registered. Rubinstein must have tried to contest this because he noted that “nothing [had] helped.” Nineteen days later Edi was made to board a train to an unknown destination.

On September 1, 1944, Rubinstein found out from a letter that Edi was in Kansk in Siberia. From this point on, the diary’s tone changes again, and one has the sense that Rubinstein no longer dared to confide his innermost thoughts. But in any case, he did not stay. Like most Jewish survivors in and from Cernăuți, Rubinstein left the region in 1946, first for Romania and later for Palestine/Israel.

Conclusion: Using Diaries as a Source

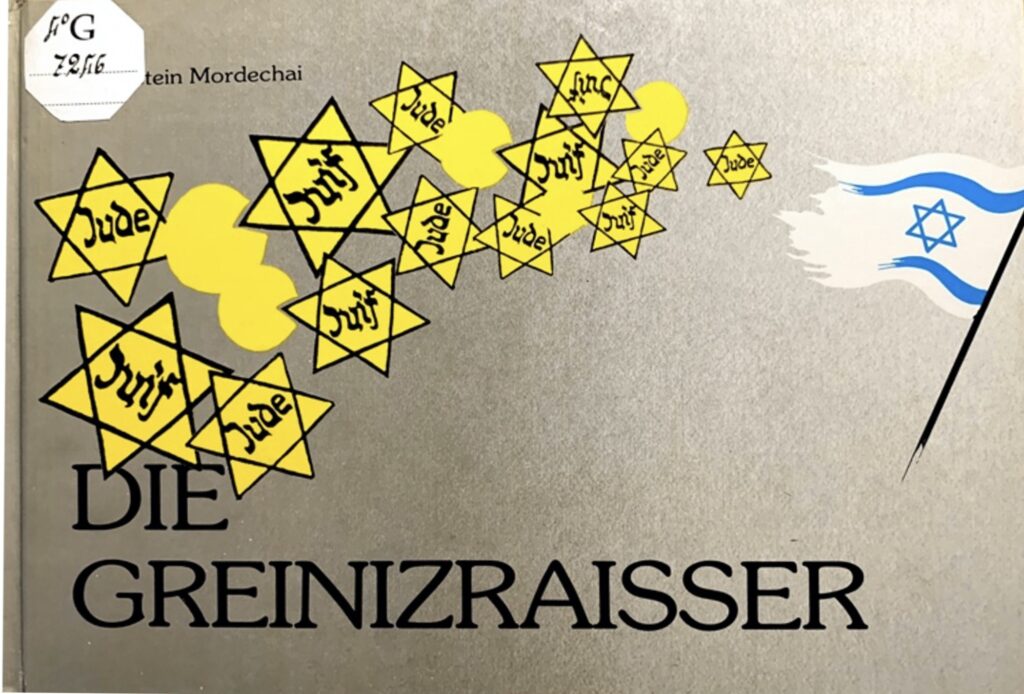

In the mid-1950s in Israel, Pinus Rubinstein published parts of his diary in a book: Aus dem Tagebuch von Ben Saar, Der jüdische Vatikan in Sadagora, 1850-1950, Vol I & 2. In the 1980s, his son Bubi (Mordechai), also published a book – a book about the family’s emigration. Rubinstein’s diary, as a mere chronicle of events written in note form and without the benefit of hindsight, only served as raw material and was never published as a whole or in its original form.

But for historians, Rubinstein’s diary is an exceptional document and source. Such sources are inevitably patchy and partial. They need to be contextualized and read with due attention to the author’s age, social background and situation, gender, political orientation, past experiences, as well as what we already know about the events. However, if we do this, they can complement our understanding of the past in crucial ways. They can tell us about the “lived experience” of the Holocaust; perceptions of time and space; and contemporaneous and changing emotions, concerns, and convictions; the complexity of people’s inner and social lives at the time of persecution and beyond. Most importantly, with their immediacy and timeliness, with their gaps and silences, diaries remind us of the open-endedness, contingency, and uncertainty of history as it happened – what German historian Reinhart Koselleck called “futures past” – and therefore what decisively influenced people’s choices at the time.33

By now, we know of many diaries covering many lived aspects of the Holocaust, but this is one of the only ones from Cernăuți. This diary therefore deserves to be explored further and more systematically. Ideally, such a source should be embedded in a thick description of social conditions and events and compared to other documents of its kind. While similar sources might not be available, it would be possible to analyze it together with other sources read through the lens of “lived experience” and gain a more comprehensive picture of the war and the Holocaust in Cernăuți.

- On the history of Jews and Jewish life in the region in general, see Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, Ghosts of Home: The Afterlife of Czernowitz in Jewish Memory (Oakland: University of California Press, 2010). On the Holocaust Romania, see Jean Ancel, The History of the Holocaust in Romania (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press and Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2011). On the immediate postwar period, see Gaëlle Fisher, “Between Liberation and Emigration: Jews from Bukovina in Romania after the Second World War,” The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 62 (2017): 115-132. ↩

- On this, see Nikolaus Wachsmann, “Lived experience and the Holocaust: spaces, sense and emotions in Auschwitz,” Journal of the British Academy no. 9 (2021): 27-58. ↩

- For this expression, see Amy Simon, Emotions in Yiddish Ghetto Diaries: Encountering Persecutors and Questioning Humanity (London/New York: Routledge, 2023), 14. ↩

- See: Alexandra Garbarini, Numbered Days: Diaries and the Holocaust (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006); Amos Goldberg, Trauma in the First Person: Diary Writing during the Holocaust (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017); and most recently, Guy Miron, Space and Time under Persecution: The German Jewish Experience in the Third Reich, trans. Haim Watzman (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 2023). See also the ongoing Balzan Bystanding Project at the University of Bielefeld. On the social and performative nature of diary writing and its social and political significance, see Mary Fulbrook and Ulinka Rublack, “In Relation: The ‘Social Self’ and Ego-Documents,” German History 28, no. 3 (2010): 263-272. Janosch Steuwer, „A Third Reich as I see it“: Politics, Society, and Private Life in the Diaries of Nazi Germany, 1933-1939, trans. Bernard Heise (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2023). ↩

- Dates of birth and death were updated to correct minor errors in July 2024. I am grateful to Jens Dreiser for pointing these out to me and sharing with me further information about Pinus Rubinstein and his family. ↩

- Unfortunately, there is no further information concerning the diary’s provenance. ↩

- See e.g., Zwi Yavetz, Erinnerungen an Czernowitz: Wo Menschen und Bücher lebten (Munich: Beck, 2008). ↩

- On this, see Irina Livezeanu, Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation-Building, and Ethnic Struggle, 1918–1930 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995); Mariana Hausleitner, Die Rumänisierung der Bukowina: Die Durchsetzung des nationalstaatlichen Anspruchs Großrumäniens 1918–1940 (Munich: Oldenbourg: 2001); Florence Heymann, Le Crépuscule des Lieux: Identités juives de Czernowitz (Paris: Stock, 2003). ↩

- E.g., the entry dated May 18, 1926. ↩

- “A Craftsman is being celebrated,” Czernowitzer Allgemeine Zeitung, 28.04.1938, source Difmoe. ↩

- This “revision of citizenship” was ostensibly about identifying Jews who had entered the country recently and illegally. But in practice, it was an antisemitic measure that led to the deprivation of civil rights and disenfranchisement of a third of Romania’s Jewish population—more than 200,000 people. This regulation was particularly problematic for residents in Romania’s border regions, such as Bukovina, who had only become Romanian after World War I. Indeed, as former citizens of other countries—in this case the Habsburg Monarchy—it was much more difficult for them to prove their continuous residency or put together the evidence required by the authorities. This measure was effectively directed against them, to disenfranchise them, and the process thus turned into a huge bureaucratic chicanery. On this, see Joshua Starr, “Jewish Citizenship in Rumania (1878-1940),” Jewish Social Studies (1941): 57–80. ↩

- Supporters of Cuza. ↩

- Nichifor Robu was a notoriously antisemitic politician. ↩

- Literally meaning: “a certificate of indigenousness.” ↩

- Admitted; in Romanian in the original. ↩

- Hirsch and Spitzer, Ghosts of Home, 109. ↩

- The rush to get married under the extreme circumstances also plays a role in the biographies of Marianne Hirsch’s parents, in Hirsch and Spitzer, Ghosts of Home, 136–137. ↩

- Some 3,000 people, including many Jews, were deported by the Soviets to Siberia just before they withdrew. ↩

- I use here the spelling from the original German even though the city was then Chernovtsy. ↩

- Romanian for a unit of foot soldiers. ↩

- In German sources there is evidence that 500 people were shot in Cernăuți, but some sources mention several thousand being killed. See Ancel, The History of the Holocaust in Romania, 271. What is certain is that in the surrounding villages many thousand people were murdered in July and August 1941. ↩

- He names three people including the concierge. ↩

- Entry dated July 10, 1941. He said they had not left the house since July 4. ↩

- One senses here Rubinstein’s urge to record not just what was happening to him but what was happening in general—a shift identified in other Holocaust diaries as well, often corresponding to the moment events become perceived as “unimaginable.” On this, see e.g., Goldberg, Trauma in the First Person, 29–31. ↩

- The actual number was probably closer to 48,000. Estimates vary between this and 55,000. ↩

- The area between the rivers Dniester and Bug in southern Ukraine, which was administered by Romania during World War II (1941–1944). ↩

- Officially, people were selected based on their profession. However, in practice, bribery played an important role. It remains a sensitive topic for many survivors. On this, see Hirsch and Spitzer, Ghosts of Home, 185. ↩

- American Jewish Archives, MS-361 World Jewish Congress Collection, H298, 8: Letter from Mayer Ebner to the United Romanian Jews of America, August 6, 1943. ↩

- Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer have, for instance, drawn attention to the relatively large number of private portraits of Jews on the city’s streets from this period and described them as “incongruous.” Indeed, analyzing these sources with care means understanding the complex mixture of anti-Jewish persecution and Jewish affirmation they capture. Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, “Incongruous Images: ‘Before, during, and after’ the Holocaust,” History and Theory, vol. 48, no. 4 (2009): 9–25; Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, „Spaziergang in der Herrengasse. Straßenfotos aus dem jüdischen Czernowitz,“ in S:I.M.O.N. – Shoah: Intervention. Methods. Documentation 1 (2014): 112–12. ↩

- These deportations took place on Saturdays and Sundays, starting in early June and were carried out in an especially brutal manner. On this, see Liviu Carare, “Roundup on the Maccabi Stadium: Insights into the 1942 Deportations of Czernowitz Jews to Transnistria,” Holocaust. Studii şi cercetări 06 (2013): 43–59. ↩

- A seminal work in this respect is Marion Kaplan, Between Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). ↩

- On November 1, 1944, he noted that he had opened a shop Peruk 2 in the Schwarzer Adler Hotel on the Ringplatz. ↩

- On this, see Reinhart Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time trans. Keith Tribe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). ↩

Jens Dreiser

Wonderful project. Pinus was my girlfriend‘s great-great-granduncle, the brother of her great-great-grandfather Leon Rubinstein. I did some research on the family and built a familytree on MyHeritage. While Pinus, his wife Pepi, their sons Edi and Bubi (Mordechai/Max) and various family members made it to immigrate to Israel, Leon died on route in Bucharest in 1947, his wife Jeanette even a year before in Bacau, Romania.

There is some information on Pinus‘ family in the publication „Die Stimme“.

A question we have been asking ourselves is how the USHMM got in possession of the diaries. According to the information on their page it was made possible by the Sosland Family, but they most likely only provided the money. It would be amazing to find out who owned the diaries before. I assume that my girlfriend’s family from

Israel would know about it if close relatives were in possession. Any information appreciated

We were actually wondering