While on my EHRI Conny Kristel Fellowship at Yad Vashem in August 2022, I discovered the author of an anonymous diary from a Hungarian Jew in wartime Budapest. The search for the identity of the author drew on clues in the text of the diary, photographs folded between its pages, census records, and school records. It traversed archives at Yad Vashem, The Hungarian National Pedagogical Library and Museum, and University of Southern California. By combining sources from archives across the world, the search was a true reflection of the international approach encapsulated in the EHRI.

I first came across the diary while in residence as the 2021-2022 Breslauer, Rutman, and Anderson Research Fellow at the USC Dornsife Centre for Advanced Genocide Research in March 2022. While USC is most well-known for their Shoah Foundation and its Visual History Archive with over 55,000 interviews, the institution’s special collections also hold a set of archival holdings relating to the Holocaust in Hungary, including the anonymous diary of a Hungarian Jew from Budapest.1

The diary is a somewhat battered document, with scratch and spill marks indicative of both its age and its journey from the dangerous streets of Budapest in 1944 to the palm-tree lined campus of the University of Southern California today. We do not know how the diary came to the USA, only that it was purchased by the University from the American Bookseller Eric Chaim Kline on April 21, 2014. Listed in the special collections as an ‘Anonymous Hungarian Jew diary, 1944-1945’, the diary – which is written completely in Hungarian – has spurred little interest in the archives since its acquisition.

Discovering the Diary

Being able to speak Hungarian, I was one of the few people at USC able to understand the diary. Its pages cover the period of March 19, 1944 – January 17, 1945, with entries referring to the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944, the continued conscription of male Jews as forced labourers, the ghettoization of Budapest, the Arrow Cross takeover in October 1944, and the disappearance of the author’s son on December 17, 1944. The diary therefore charts life through one of the most momentous parts of the Holocaust in Hungary, recounting daily activities during a time of deportation, persecution, and extermination. Following the German occupation of Hungary, over 400,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the majority of them were murdered upon arrival. Only the Jews of Budapest avoided deportation, after international outcry halted deportations in the summer of 1944. When the Arrow Cross came to power, their reign of terror saw Jews in the capital attacked and rounded up, leading to the well-known instances of militiamen shooting Jews into the Danube.

As well as recording these events, the diary also gives an insight into how the author experienced them, both through his own reflections and in the way he wrote. The form of the entries changes distinctly after the Arrow Cross takeover in October 1944, where the author started to use rhetorical questions, displaying the uncertainty of daily life. ‘But where?’, he questioned about him and his family’s living conditions on October 17, followed by ‘but for how long?’ on October 20, as he bemoans new antisemitic restrictions. His use of rhetorical questions increases more when talking about the disappearance of his son on December 17, in a clear reflection of his growing anxiety. ‘If they find out that he is a Jew, what will happen then?’ he questioned, admitting in his diary that ‘I don’t know where to look for him?’. A week later, on December 29, he wrote ‘where did they take him?’, suggesting that his son was arrested by the Arrow Cross militia, as so many were in the winter of 1944.

Identifying the Author

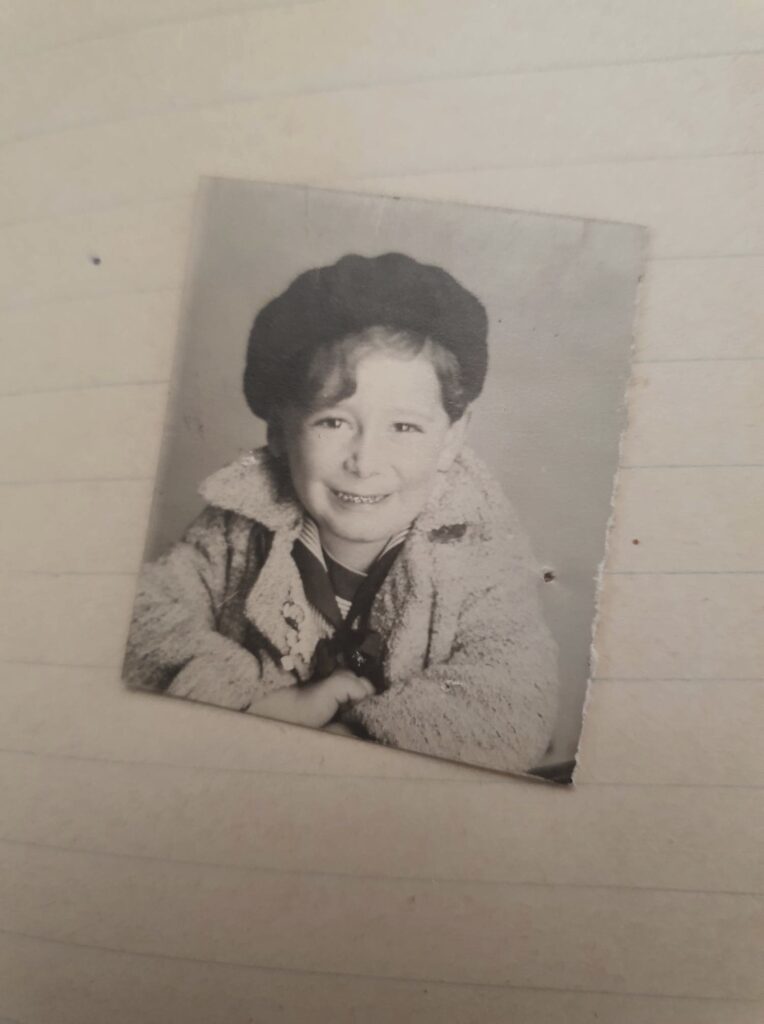

Throughout the diary, the author never writes the full name of any of his family members. He refers to his wife and son by their first names only: Ilona and Robi. The diary also includes two photos of Robi and one of Ilona. One of the photographs of Robi – a small passport-sized photograph – shows a young boy of around five years old, dressed in a beret and fluffy coat, smiling happily into the camera. On the back of the picture is the date 1935. This provides the first clue of the author’s identity, giving his son Robi the approximate birthdate of 1930.

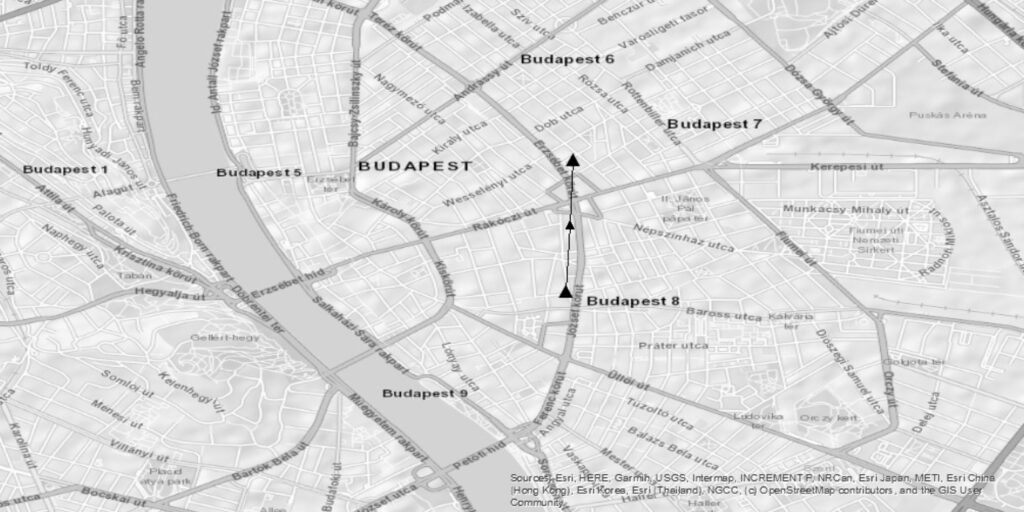

A possible date of birth and the first name of his son is not, however, enough to identify the author. A more concrete clue comes from a diary entry on June 21, 1944, where the author bemoaned the latest antisemitic law which forced him and his family to move into the Budapest ghetto. ‘Today’, he wrote, ‘we had to leave the R. Sz. 22 apartment where we have lived for 40 years.’ Written in light pencil in square brackets above this entry, by another unknown person – most likely another researcher attempting to identify the author – is the Budapest street name ‘Rökk Szilárd’. This is a logical explanation for the ‘R. Sz.’ referred to in the diary, placing them in the south-eastern part of the city, just a 20-minute walk south of the Dohany Utca Synagogue and the Jewish quarter of Budapest.

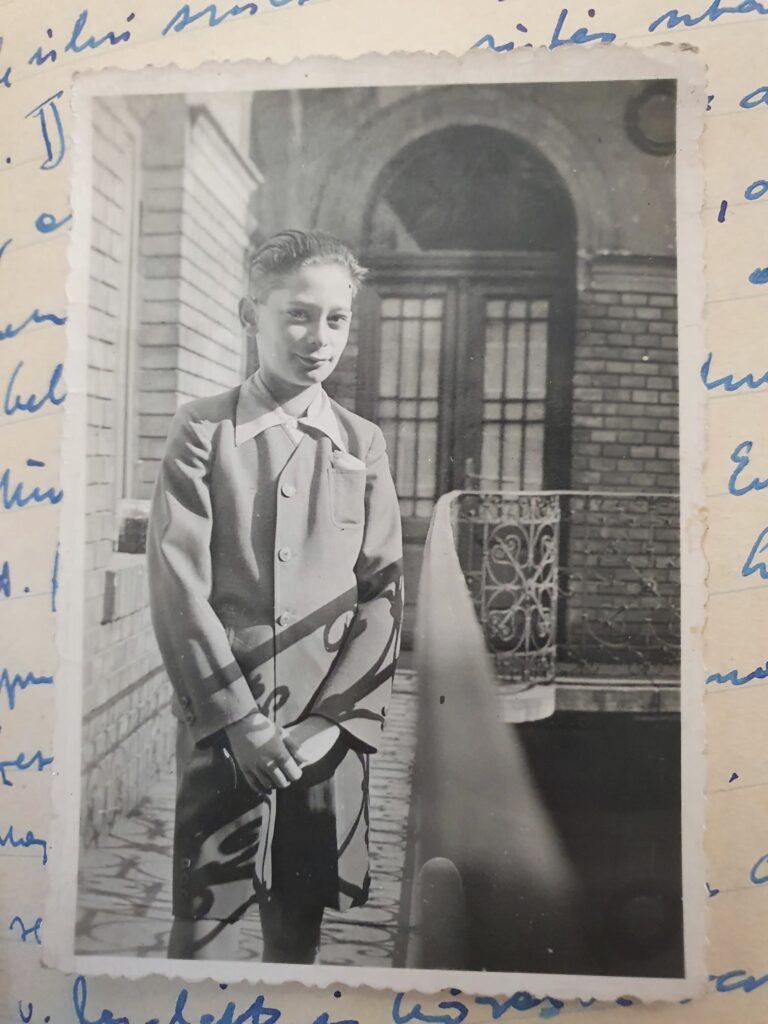

During my residence as a Conny Kristel Fellow at the Yad Vashem Archives, I was able to access Hungarian census records from both 1941 and 1945.2 Today, these documents act as a way of tracing Hungarian Jews at the beginning and immediate aftermath of the war and understanding their position within society. Looking up the address Rökk Szilárd 22, there were multiple entries from what would have been an apartment block. Indeed, one of the other photographs of Robi shows him standing by the railings of an internal courtyard balcony in a traditional Budapest block of flats. Only one of the records from Rökk Szilárd 22, however, could have been that of the author. Here, the dated picture of Robi becomes important.

At the 1941 census, three generations of the Poltizer family lived at flat number 22 on the third floor of Rökk Szilárd 22.3 A grandfather, Miksa Politzer (b. 1867) with his wife, a Jenő Politzer (although interestingly not with his wife) (b. 1893), and the child Robi Politzer (b. 1931). They also have a live-in maid. One of the questions asked in the 1941 census is how long each individual has lived there. For this entry, Jenő declares that he has lived there since 1907. This places him as living there just under 40 years by 1944, thus matching with his diary entry. Several points of data from the 1941 census records do, therefore, match with the details we gain from the diary, suggesting that the author of the diary was in fact Jenő Politzer.

This is further supported by the 1945 Hungarian Census of Jews, where there are only three people living at the same address.4 These are Jenő Politzer, his wife (who has now moved to live with him), and Miksa Politzer’s wife. Unfortunately, the census data does not tell us the names of the women living at the address, as Hungarian tradition records wives’ names as ‘Politzer Jenőné’, ‘Mrs Jenő Politzer’. Within the 1945 documents, the absence of Robi – who would have been around 14 years old at the time – is conspicuous. His omission from the census correlates with his disappearance in December 1944. Because he remains missing in records in 1945, it appears probable that he was murdered by the Arrow Cross in December 1944.

While we don’t know for certain what fate befell Robi during the war, we can piece together part of his life before his disappearance, which further suggest that this is a correct match between census and diary. Hungarian school records are remarkably well preserved and digitized, especially for large cities like Budapest. Robert Politzer appears in the Yearbook class lists of a school just a 15-minute walk from his home on Rökk Szilárd Street. The school – the Madách Imre Gimnázium, which still exists today – was a Hungarian state school in the VII district of the capital. As a Gimnázium, inherited from the German-style of education in the late nineteenth century, the school was elite in its nature, providing a humanistic education based on Latin and Greek literature and language.5 Robi appears on class lists in 1942 and 1943, in classes II and III.6 Those in class II are usually 11 years old, and class III usually 12 – ages which correlate with Robi being born in 1931. There are no records of Robi in further years of the school, despite school yearbooks being available up to 1948, further corroborating his disappearance.

Conclusion

Identifying the author of the diary gives a name to the experiences that it recounts. It attributes the words held within the diary to a named individual, giving him credit and acknowledgement and testifying to his life. It also enables us to learn more about Robi Politzer, a victim of the Holocaust, and personalise the history of his persecution. When we read the diary, we get merely a history of his disappearance – a story that defines his life simply as a part of the Holocaust. Knowing his full name and matching this to his school records, however, broadens this history and makes it more personal. Instead of learning simply about his disappearance and presumed death, we can learn about his schooling and his everyday life – the walk he took to school, the subjects that he studied, and the friends that he made there. This must surely be a crucial part of Holocaust research, as we seek to record and give life through memory to those murdered during genocide.

Nonetheless, identifying the author raises ethical challenges. We do not know how the diary made its way to the United States of America, as the archival trail on the Politzer family runs cold after 1945. The diary is an intimate document, in which the author expresses his inner-most anxieties and fears. There is no evidence that he ever expected the diary to be published; instead, it clearly held a deeply personal function, carrying well-worn pictures of his loved ones. Moreover, I have been unable to find any testimonies or written accounts of the Holocaust from Jenő Politzer, providing no precedent of him sharing his experiences with the public. Despite these uncertainties, the diary sits in the archives of the USC special collections, open and accessible for research. Furthermore, as the diary was bought by the University from a bookseller, rather than donated by the author or his family, its anonymity most likely stemmed from a lack of knowledge rather than intent on the part of the author. Because of this, I hope that identifying the author does him, the public, and historical record, a service, contributing to our understanding of the past.

The case of this diary is a prime example of the transnational nature of Holocaust research. A physical object housed in the archives of a University in Los Angeles is hereby connected through research to census records digitised in Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, to school records in Hungary. Only when bringing all three of these together can we tell even a snippet of the full history of Jenő, Ilona, and Robi Politzer. Much remains to be said on the diary, and there are still many unknowns – not least surrounding Ilona. This blog post offers an insight into the diary and its content, and shows how with international and cross-archival research it can be possible to uncover the identities of previously-unknown authors.

Jenő Politzer’s Diary entry from June 21, 1944. From the University of Southern California Special Collections – ‘Anonymous Hungarian Jew Diary, Collection no. 6071’.See fullscreen visualisation of “Jenő Politzer’s Diary entry from June 21, 1944”

Mapping the documents was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

Bibliography

Gergely Kunt, ‘How Do Diaries Begin? The Narrative Rites of Adolescent Diaries in Hungary’, European Journal of Life Writing IV (2015), 30-55.

István Deák, ‘The Peculiarities of Hungarian Fascism’, in Randolph L. Braham and Bela Vago (eds.), The Holocaust in Hungary: Forty Years Later (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 43-51.

Istvan Pal Adam, Budapest Building Managers and the Holocaust in Hungary (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

Laszlo Csosz and Laura Csonka, Murdered on the Verge of Survival: Massacres in the Last Days of the Siege of Budapest, 1945, Parts I & II, EHRI Document Blog, February 8, 2017 and July 5, 2017.

- Anonymous Hungarian Jew diary, Collection no. 6071, Special Collections, USC Libraries, University of Southern California https://archives.usc.edu/repositories/3/resources/939. ↩

- YVA M.61 ‘Census of the Jews of Budapest, 1941’, file range: JM/30368-JM/30393; JM/31055-JM/31113; JM/31664-JM/31688; JM/32363-JM/32365. Yad Vashem holds microfilm copies of the original files from the Budapest City Archives, entitled: ‘Az 1941. évi népszámlálás budapesti felvételi és feldolgozási iratainak gyűjteménye’ (Collection of recording and processing documents of the 1941 census in Budapest), HU BFL IV. 1419.j. See EHRI portal: https://portal.ehri-project.eu/units/hu-002733-hu_bfl_iv_1419. ↩

- Politzer Miksa and Politzer Jenő – Rökk Szilárd 22, YVA M.61 JM/31673, pp. 124-127. ↩

- Politzer Jenő – Rökk Szilárd 22, YVA M.61 JM/36517, pp. 704-5. ↩

- Tibor Frank, Double Exile: Migrations of Jewish-Hungarian Professionals through Germany to the United States, 1919-1945, (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2009), p. 56. ↩

- A Budapest VII Kerületi Magy. Kir. Allami Gimnázium Evkönyve 1942 (The Budapest VII District Hungarian State School Yearbook 1942), National Pedagogical Library and Museum, Digitheca Database, p. 46; A Budapest VII Kerületi Magy. Kir. Allami Gimnázium Evkönyve 1943 (The Budapest VII District Hungarian State School Yearbook 1943), National Pedagogical Library and Museum, Digitheca Database, p. 34. ↩

Dalia Ofer

Thanks, this is an important contribution to learn how to identify and look for details that are missing. It demonstrate how sharing and working together with different disciplines is important.

Joan Salter

Brilliant research using your own language skills to a contemporary account of the events relating to the Holocaust in Hungary and its effects on one family.

Thank you Barnabas.

Barnabas Balint

Thank you Joan for your ongoing support!

Madeline Vadkerty

Very interesting article! I enjoyed reading about the research—

Rena

I am currently teaching a class on Holocaust to adults. Has the diary been translated into English? If so is it possible to read it? Very excited about this article

Barnabas Balint

Thank you for your interest in it! I’m afraid it hasn’t been translated yet – its only available as the handwritten original in the USC archives, although a summary is available on their website here: https://archives.usc.edu/repositories/3/resources/939