Thousands of Jews throughout Europe, facing a shrinking universe of options and increasingly desperate circumstances, wrote to the representatives of the very governments that were persecuting them to ask for clemency from anti-Semitic measures during the Holocaust. They employed a variety of rhetorical strategies in their appeals, hoping that their words would be sufficiently convincing to obtain the reprieve that they sought. Vastly understudied, such entreaties reveal firsthand information about how Jews were experiencing persecution in real time during the period. The correspondence demonstrates how individuals attempted to cope with their predicament in the moment and maintain a sense of agency and dignity as they became increasingly isolated from social and economic life. Jews throughout Europe wrote letters to their governments, but the study of petitioning is only emerging now.1

Anti-Semitic ideology appeared in its modern form in Slovak politics starting in the 19th century in the economic-social, national and religious arenas. Almost all of the political parties in Slovakia leveraged anti-Jewish sentiment, radicalizing their economic and political agendas. The Hlinka’s Slovak People’s Party (HSĽS) exploited this trend with the greatest skill, and assumed power in Slovakia in the autumn of 1938. The party established a totalitarian regime that was intrinsically anti-Semitic. The first discriminatory measures against Jews were accompanied by hate-filled propaganda, pogroms and the preparation of legislative norms.2

Hitler’s Germany pressed for the establishment of a satellite Slovak state in March 1939. The anti-Semitic platform gained a new impetus, forum and dynamism. The circumstances of the state’s establishment created the ideal conditions for the implementation of anti-Jewish policy. Pressure from the Third Reich increased for Slovakia to address the so-called “Jewish question,” which was in alignment with the new government’s objectives. It played the anti-Semitic card in a calculated and pragmatic way. Anti-Jewish doctrine and its practical application in public life became mainstream. The status of Jews in Slovakia became an ongoing and defining issue of regime policy. It influenced all areas of the state’s domestic and foreign policy and impacted all segments of the population either directly or indirectly.3

The government issued dozens of ordinances and hundreds of decrees that systematically deprived Jewish citizens of their political, economic, social, and ultimately basic civil and human rights. This trend culminated in the issuance of Regulation no. 198/1941 Sl. z., known as the Jewish Code in September of 1941. Consisting of 270 paragraphs, it is considered one of the harshest anti-Semitic legal norms in modern European history. The Code confirmed and toughened all previously existing anti-Jewish legal norms. It established a new definition of Jewishness on the basis of racial criteria and ordered that Jews wear a yellow Star of David on their clothing. However, the President of the Republic, Jozef Tiso4, was accorded the power to grant exemptions, which generated thousands of desperate pleas from Jews nationwide.

For the past four years, I have been studying letters written by ordinary individuals to Tiso between 1939 and 1944. The letters are located in the Slovak National Archive (Slovenský národný archív) in Bratislava, Slovakia, in the fond for the Office of the President of the Slovak Republic (f. Kancelária prezidenta Slovenskej republiky). Slovak historian Ivan Kamenec estimates that there may be as many as 20,000 petitions in the files of the President’s Office including direct appeals along with ancillary correspondence.5 The fond consists of 263 boxes of presidential documents covering a broad array of subjects.

When I first saw the entreaties, I was struck by their emotionality. Though Slovak historians were aware of this correspondence, it had not yet been studied systematically. Examining the letters allows us to bring victims’ voices into the historical narrative and humanizes this history, which is so often discussed in terms of numbers, statistics and pieces of legislation. I also became interested in researching the fates of the individuals who wrote to Tiso.

Jews wrote for a variety of reasons to Tiso based on their unique circumstances – they asked for permission to keep their small businesses, their jobs, radios and other personal property, or to be able to marry the person they loved, receive permission to be adopted, or avoid the confiscation of the funds in their bank accounts and safe deposit boxes, among other reasons. As I researched the fates of the letters’ authors, I learned of many tragic and dramatic outcomes – people jumping out of transports, hiding, becoming the victims of medical experimentation, imprisonment, being shot, or perishing in the gas chambers.

One individual who wrote to Tiso was Alžbeta Helena Donathová6. Born on December 10, 1924 in Diviaky nad Nitricou, she was the illegitimate child of a Jewish mother and a Catholic father. Diviaky nad Nitricou was a village of approximately 500 people located in central Slovakia 175 km northeast of the Slovak capital of Bratislava. Two imposing church spires dominate the skyline as one approaches the village. The structure dates back to at least the 12th century.7 A convert, this was the place where Alžbeta turned to for help as her situation became increasingly dire.

When Alžbeta was born, her mother did not enter her name into the Jewish birth registry. She decided that her daughter should decide for herself once she was of legal age. At age 16, in 1941, Alžbeta converted to Catholicism. However, the government of the Slovak State identified her as a Jew, since her parents were not married and her mother was 100% Jewish. The Jewish Code defined Jewishness along the same “racial” lines as the Nuremberg Laws.

Alžbeta lived with her mother and grandmother. Her mother was lame in one leg and her grandmother was nearly blind, so the responsibility of taking care of the family fell on Alžbeta’s shoulders. Alžbeta had recently completed middle school and needed to find a job so she could support her household. However, no one wished to hire her. Unable to find work without proof of “Aryan” status, Alžbeta decided to write to Jozef Tiso. She would eventually turn to him three times between September 1941 and June 1942.

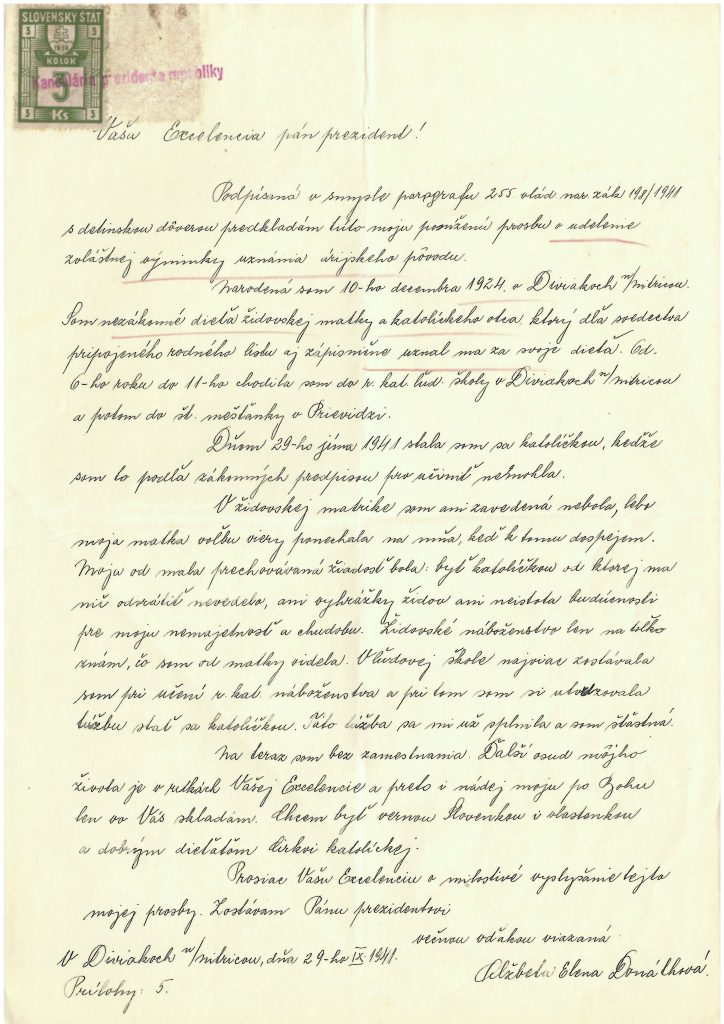

In her first letter, dated September 26, 1941, she writes:

My desire since childhood was to be a Catholic, nothing could convince me otherwise, not the threats from Jews nor the uncertainty about the future because of my poverty. I only know about the Jewish religion what my mother has told me. In school, I studied the Roman Catholic religion. Doing so strengthened my desire to become a Catholic. This desire has already been fulfilled for me and I am happy. But now I am out of a job. My faith in life is in the hands of Your Excellency, and therefore I place my faith in you only behind that of my faith in God. I wish to be a faithful Slovak, a patriot, and a good child of the Catholic Church.

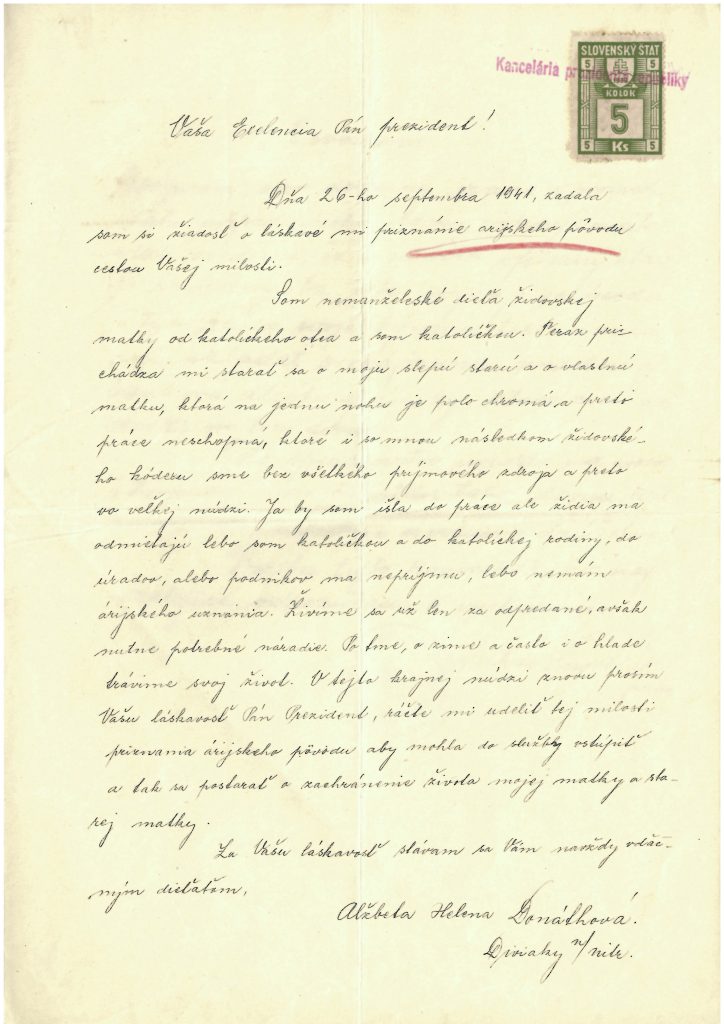

A letter from her priest confirmed that Alžbeta was telling the truth about her circumstances and the sincerity of her conversion to Catholicism. Months went by. Alžbeta remained unemployed, and she received no response from the President’s Office. Her predicament was becoming increasingly difficult. Undaunted, she wrote to Tiso a second time, in an undated letter, stating:

I need to take care of my blind grandmother and my elderly mother, who is semi-lame in one leg and therefore unable to work. All three of us, because of the Jewish Code, are without any source of income and therefore in great need. I would work, but Jews reject me because I am a Catholic, and since I am not recognized as an Aryan, no Catholic family, offices, or businesses will hire me. We only live off of what we can sell, even absolutely necessary items. We spend our lives living in darkness, in cold, and often in hunger. In this state of extreme distress, please again, Mr. President, please grant me the grace of Aryan status so that I may enter into service and thus go about saving the lives of my mother and grandmother. I am a forever grateful child to you for your kindness.

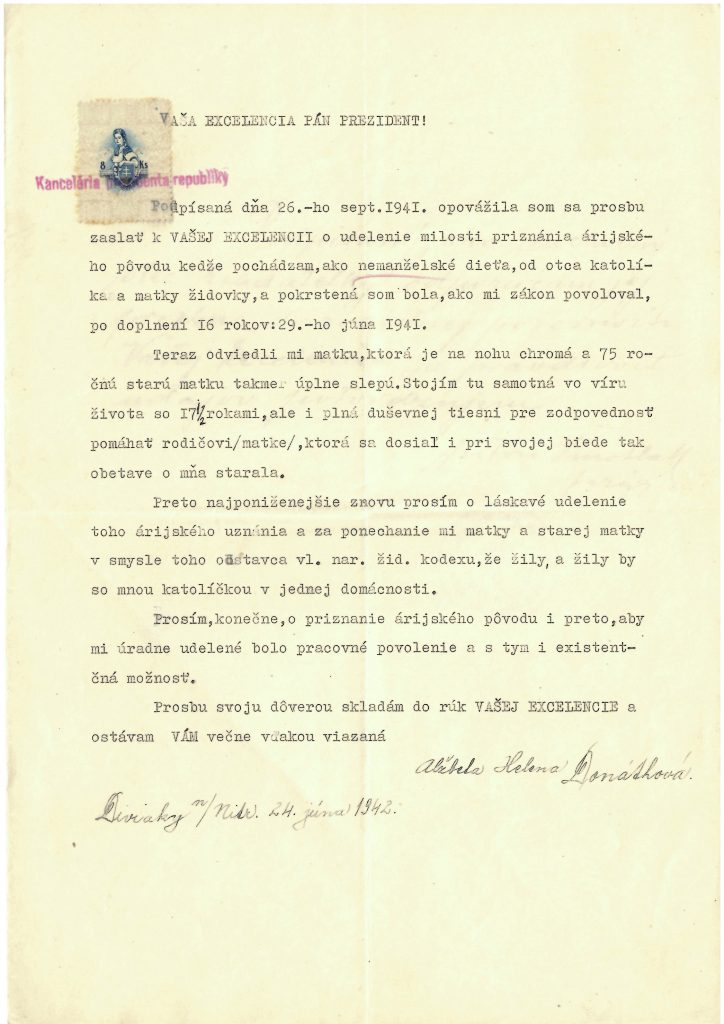

In June of 1942, Alžbeta’s mother and grandmother were deported to Auschwitz where they most likely perished upon arrival given their ages and physical handicaps. The reason why the Slovak State did not deport Alžbeta with her family is unclear. Alone at the age of 17, she became increasingly dependent on the charity of others to meet even her most basic needs. She made one last desperate attempt to convince Tiso to grant her “Aryan” status so that she could support herself and her family. On June 24, 1942, she wrote:

On September 26, 1941, I dared to ask Your Excellency to grant me the grace of acknowledging my Aryan origin, since I am the illegitimate child of a Catholic father and a Jewish mother. I was baptized when I turned 16 on June 29, 1941, as soon as the law permitted. Now they have taken away my mother, who is semi-lame on one leg, and my 75 year old grandmother, who is almost completely blind.

I stand here alone on the crossroads of life at the age of 17 ½, but also deeply distressed about my responsibility to help my parent /mother/, who has always taken such good care of me despite her misery. Therefore, I most humbly ask again for the kind granting of that Aryan status to help my mother and grandmother within the meaning of that paragraph of the Government Decree of the Jewish Code that they lived and will live with me, a Catholic, in the same household.

Finally, I ask for recognition of Aryan origin so I can officially be granted a work permit to support myself. I trustfully place my request in the hands of Your Excellency and remain forever bound by thanks to you.

From the words she used, it would appear that Alžbeta believed that her mother and grandmother would be permitted to return home if Tiso granted her request. Many of the letters in the files display naïve assumptions. In addition, Alžbeta’s appeal contains both religious as well as patriotic language which is typical for such correspondence. Most likely, this was because Tiso was a religious as well as a secular authority and the goal of writing such petitions was to be convincing. Though it is unclear whether those who converted to Christianity did so out of religious conviction, or because they hoped that doing so would alleviate their persecution, the letters from converts often highlight religiosity, along with a distancing of oneself from one’s Jewish origins, as one can see in Alžbeta’s case.

My research involves examining the letters and the content of their files in addition to visiting regional archives where it is sometimes possible to find additional information about the letter writer. I also attempt to learn the fates of those who wrote their appeals. Sometimes I am able to find a lot of information, other times I can only surmise the person’s ultimate fate. I became very interested in how the government processed these appeals, given that the Office of the President rejected more than 95% of the applications.8

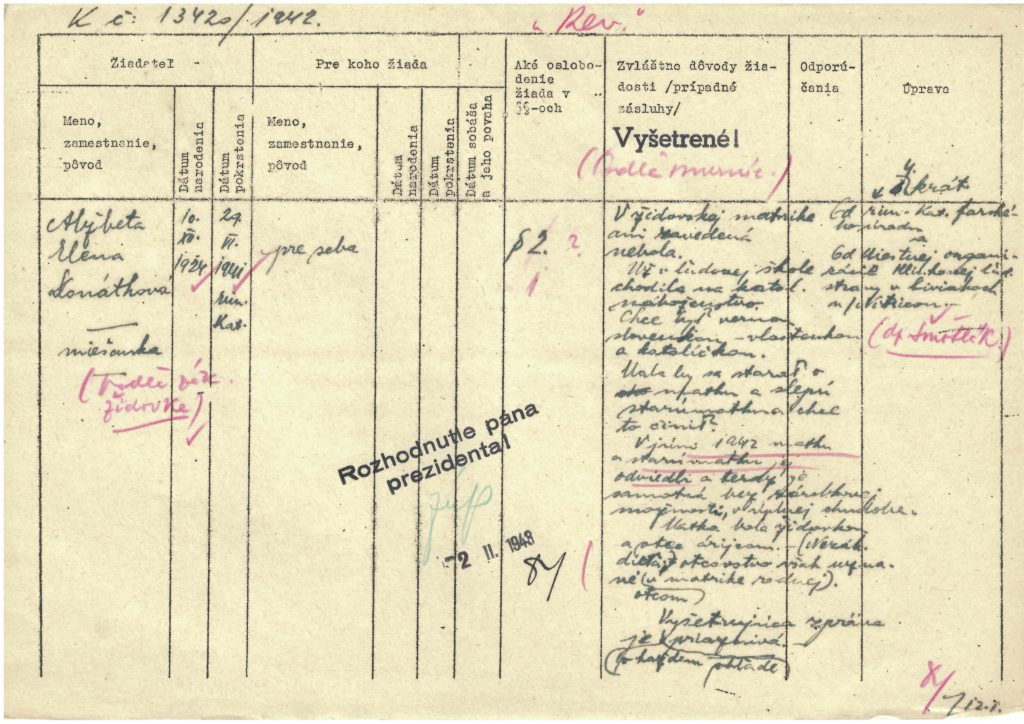

How did the government process Alžbeta’s letters?

As was customary, the Office of the President created a document called a rubric which reduced the applicant’s situation down to one page. This document is proof that these letters were actually read, a question I often receive. The rubric synthesized what the person wanted, their arguments and any extenuating circumstances that might be relevant for making a decision. This required an attentive reading by the staff member creating the document. If an immediate rejection was made, the application was filed away, and a negative response was sent to the applicant with a copy sent to the district office where the applicant lived. In some cases, the applications were investigated, which is the case with Alžbeta.

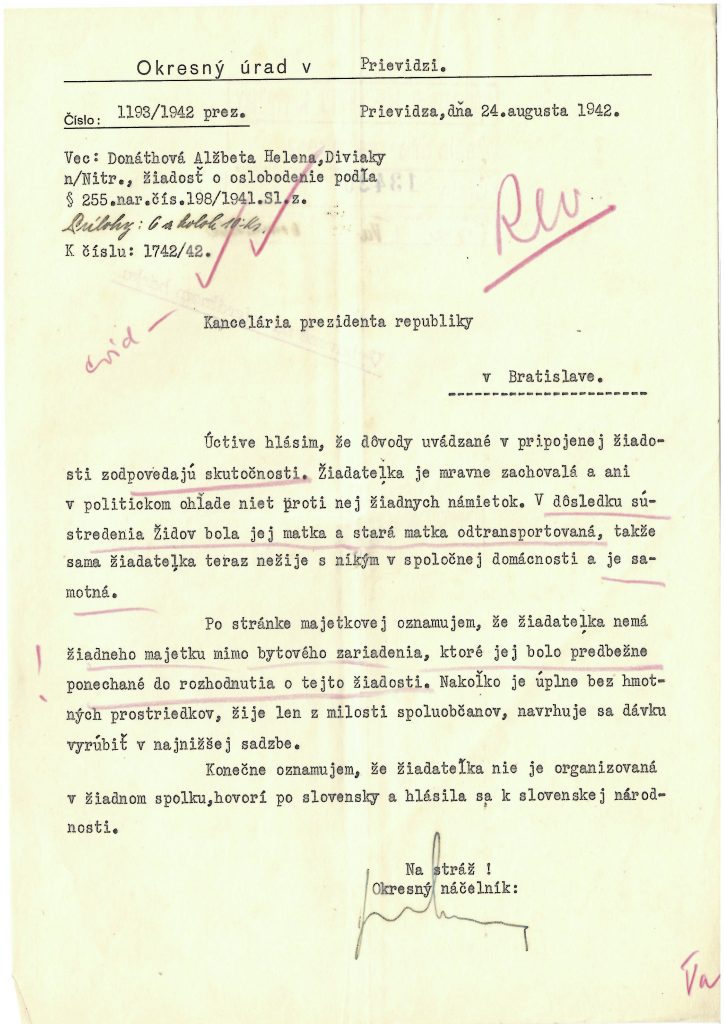

The President’s Office decided to investigate Alžbeta’s situation in July, 1942. There was a large backlog of requests from all over the country and only a limited staff to handle them. The Investigations began with a ten-part questionnaire to the district office. In Alžbeta’s case, that was in Prievidza. The questions covered a range of topics concerning the veracity of the applicant’s statements, ethnicity, political reliability, the language spoken at home, organizational affiliations, and whether the applicant lived a morally upright life followed by queries about the applicant’s financial holdings. There were questions about the political reliability of other members of the household, and in the case of married applicants, whether they were properly married and how they were raising their children. Since these questions did not apply to Alžbeta, they were crossed out, another indicator that these letters were indeed read. The final question asked how much money the applicant could afford to pay if an exemption was granted, since fees were determined individually at the discretion of the President’s Office.

Responding to the questionnaire on August 24, 1942, the District Office in Prievidza stated:

I declare that the reasons given in the attached application correspond to the facts. The applicant lives a moral life, and there are no political objections to her. As a result of the concentration of Jews, her mother and grandmother were transported, so the applicant herself now does not live with anyone in her household and is alone. In terms of property, I would like to inform you that the applicant does not have any property other than a few home furnishings which she has put aside as she awaits the decision on her application. Since she is entirely without material means, she lives only thanks to the kindness of her fellow citizens, so we propose setting the lowest possible fee. The applicant is not affiliated with any associations. She speaks Slovak and identifies herself as a Slovak.

En garde! District Office (illegible signature)

The deportations carried out by the Slovak State had begun on March 25, 1942 and continued until October 20, 1942. On January 2, 1943, Alžbeta’s priest wrote a letter to Tiso. This indicates that Alžbeta was not deported by the Slovak State. His letter makes it clear that Alžbeta was starving. In the letter, he writes:

The person in question wrote about her need for an exemption recognizing her Aryan origins from the Prime Minister’s Officer on July 5, 1941, and from Your Excellency on September 26, 1942. This request has not yet been granted. The applicant stands utterly alone in the world without kin and especially without the possibility of maintaining her physical life because she cannot apply for a job anywhere without a work permit. For this existential necessity, I, the undersigned, beg you to kindly grant her the needed exemption…she stands here poor, without a home, and with no money…

Alžbeta’s fate

On February 6, 1943, the President’s Office denied Alžbeta’s application. The enclosures, such as her baptism certificate and birth certificate were returned to her. From that point on, we only know that Alžbeta’s name shows up on a martyr’s list, but we do not know how or where she perished and when or if she ever learned of her mother’s and grandmother’s fates. At the time of her death, she was most likely eighteen or nineteen years old.

Bibliography:

Gruner Wolf and Pegelow Kaplan, Thomas. Eds., Resisting Persecution: Jews and their Persecution during the Holocaust (New York, Berghahn Books, 2020)

Hyrja, Jozef. Tisovi poza chrbát (Bratislava, Hadart Publishing, 2020)

Kamenec, Ivan. Tragédia politika, kňaza a človeka, Dr. Jozef Tiso 1887 – 1947. Bratislava, Premedia Group, 2013.

Kamenec, Ivan. Po stopách tragédie. Second Revised Edition. Bratislava: Premedia, 2020.

Vadkerty, Madeline. Slovutný pán prezident: Listy Josefovi Tisovi. Žilina: Absynt, 2020.

Ward, James Mace. People who Deserve it: Jozef Tiso and the Presidential Exemption, in: Nationalities Papers, 2002, Volume 30, Issue 4, p. 571-601. 30:4, 2002

Ward, James Mace. Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Jozef Tiso and the Making of Fascist Slovakia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

Internet Sources:

Web site of the Holocaust Documentation Center: www.holokaust.sk

Text of the Jewish Code in Slovak: https://www.upn.gov.sk/data/pdf/vlada_198-1941.pdf

Web site for the Roman Catholic church in Diviaky nad Nitricou: http://www.farnostdiviaky.sk/

Archival Sources:

Alžbeta’s file in the Slovak National Archive: Ministerstvo vnútra Slovenskej republiky, Slovenský národný archív, fond Kancelária prezidenta Slovenskej republiky, 1939 – 1945, archívna škatuľa číslo 144, číslo spisu 1742.

- See Gruner, Wolf and Pegelow Kaplan, Thomas. Eds., Resisting Persecution: Jews and their Persecution during the Holocaust.New York: Berghahn Books, 2020. ↩

- Ivan Kamenec and Madeline Vadkerty, Anti-Semitism and the Ľudák Regime, paper delivered online at a conference conducted under the auspices of the Holocaust Documentation Center in Bratislava, September 8, 2020, entitled Slovakia and the Holocaust: Histories and Legacies of a Model Nazi Ally. To be published. See: https://www.facebook.com/events/1512682472237102/?ref=newsfeed ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jozef Tiso, (1887 – 1947) was the president of the Slovak State from 1939 to 1945 and a Roman Catholic priest. On April 15, 1947, the Czechoslovak National Court (Národný súd – NS) sentenced him to death and hanged him for “state treason, betrayal of the antifascist partisan insurrection and collaboration with Nazism.” See Ward, James Mace. Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Jozef Tiso and the Making of Fascist Slovakia.Ithaca:Cornell University Press 2013. ↩

- Kamenec, Ivan. Tragédia politika, kňaza a človeka, Dr. Jozef Tiso 1887 – 1947. Second Revised Edition. Bratislava: Premedia Group, 2013. ↩

- Slovak National Archive (Slovenský národný archív), f. Kancelária prezidenta Slovenskej republiky, b. 144, f. 1772. ↩

- For information about the Catholic Church in Diviaky nad Nitricou, see: http://www.farnostdiviaky.sk/. ↩

- See Ward, James Mace. People who Deserve it: Jozef Tiso and the Presidential Exemption in: Nationalities Papers, 2002, Volume 30, Issue 4, p. 571-601. ↩

Karen Egerer

Such important work, Madeline. Thank you for doing it.

Marvin Perlman

Madeline, I appreciate receiving this. You are doing important work. Most religions are about do unto others as you would have others do unto you. Tiso surely saw himself as religious and not evil and yet he committed an evil act. I believe this is not unusual unfortunately.