The questionnaire of the Hehahalutz office for those interested in Hachshara training during the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in this post gives insight into one of the problematic ways of emigration in the early years of the occupation. Hachshara activities changed considerably at that time, as well as the social character of its participants.

Hachshara – i.e., professional, ideological, and practical training for life in Palestine, represented the necessary precondition of emigration for Zionists in interwar Czechoslovakia. The particular focus was put on preparation for industrial and primarily agricultural work in Palestine and on the means of the so-called economical “productivization” of the Jews to alter the specifically Jewish societal structure, mostly in Palestine but also in the Diaspora.1

Zionism was not a mass movement for the Jewish population in Czechoslovakia in the interwar period, and Hachshara agricultural activities were not in the sphere of interest of the majority of Jewish youth. In general, Jews in Bohemia and Moravia were settled in industrialized urban and metropolitan centers. Prague represented the most active and influential Jewish center in Bohemia. A similar process of mass migration to industrial and administrative centers and rapid depopulation of Jewish countryside communities took place in Moravia with the Jewish center in Brno. The majority of the Jewish population in Czechoslovakia were involved in trade, commerce, and industry. Jews were lawyers, physicians, owners of midsized and small businesses, representing mostly middle classes, educated families, un-experienced in agricultural work and farming.

Shortly after the Nazi occupation, Jews who had lost their positions or whose business was confiscated attempted various substitute activities. The idea of retraining that was an integral part of the Zionist program in the form of the so called „normalization“ of the Jewish nation and its job structure mentioned met with even more positive response from Jews since they were gradually excluded from various types of employment in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The social character of Haksharot changed. Training centers hitherto reserved for Zionists and predominantly run under the supervision of the Hehalutz – Movement of the Zionist Work Pioneers (founded in 1917 in Palestine), became coveted places, especially for the younger generation that sought for emigration options. However, possibilities of vocational training and requalification became more diversified, at least in their bureaucratic structure.

In the course of the interwar period, the Zionist clubs and organizations were unified under the umbrella Central Zionist Union (Ústřední sionistický svaz). Shortly after the occupation, all Zionist organizations had to stop their activities undertook now by the Central Zionist Union – the Palestinian Office (Ústřední sionistický svaz – Palestinský úřad) and its new organizational structure. Besides the departments dealing with funding of the Zionist activities (Karen Kajemet le-Israel, Karen Hajesod), the other relevant department were Hehalutz – an umbrella organization of the pioneering youth movement, organizing vocational training in agriculture. And the Jewish Help for the Young (Židovská pomoc mladým), taking care of the emigration of the Jewish youth aged from 12 to 17 years. In July 1939, the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Prague (Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung/Ústředna pro židovské vystěhovalectví v Praze). Soon after that, the centralization of the Zionist activities became even more intense, and the organization of the Zionist emigration activities even more difficult.2

Initially, before the occupation, emigration was considered especially by the younger Zionist generation of all social strata, who were trained for agricultural life in Palestine, and by the Jews with financial guarantees sufficient for the foundation of a small business or agrarian entrepreneurship in Palestine. Emigration certificates were a necessary precondition for emigration. The British Mandate Administration considerably limited their number. After the occupation, there was a rapid growth of applications for emigration, and it was the Palestinian Office itself that recommended appropriate candidates to the British Embassy directly, while the number of certificates was even more limited. Therefore, candidates had to submit an extensive questionnaire examining their ability to work in agriculture and their potential to contribute to the welfare of the Jewish community in Palestine. Priority was given to young families with children, already trained for the agricultural or working forms of occupations in Palestine. A certain amount of certificates was still reserved for those who had sufficient financial guarantees. Thus, participation in the Hachshara has become a considerable advantage and often the only one chance for dispossessed younger Jewish applicants to emigrate.

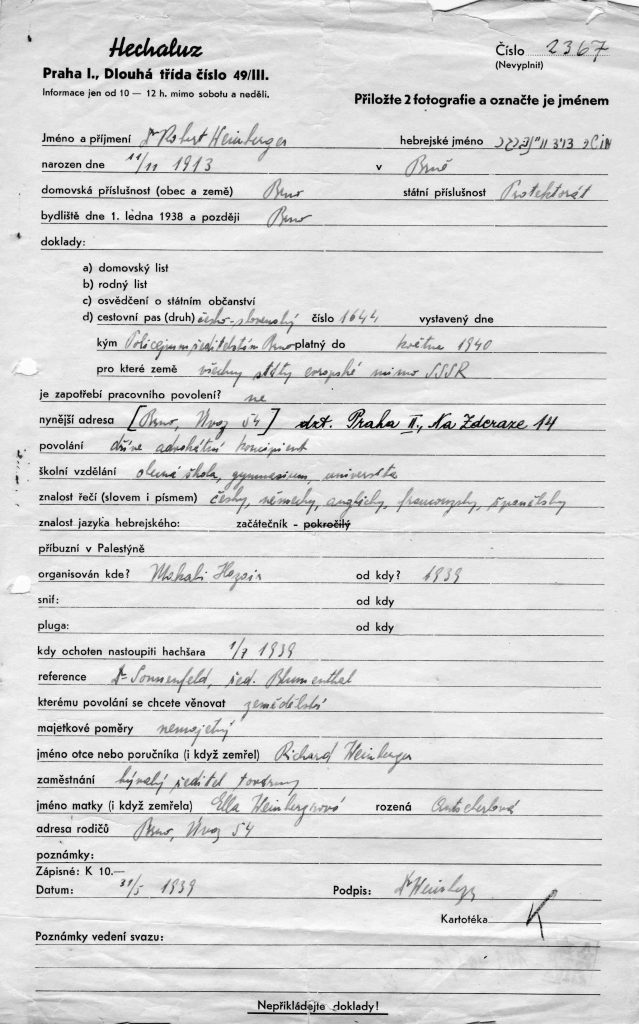

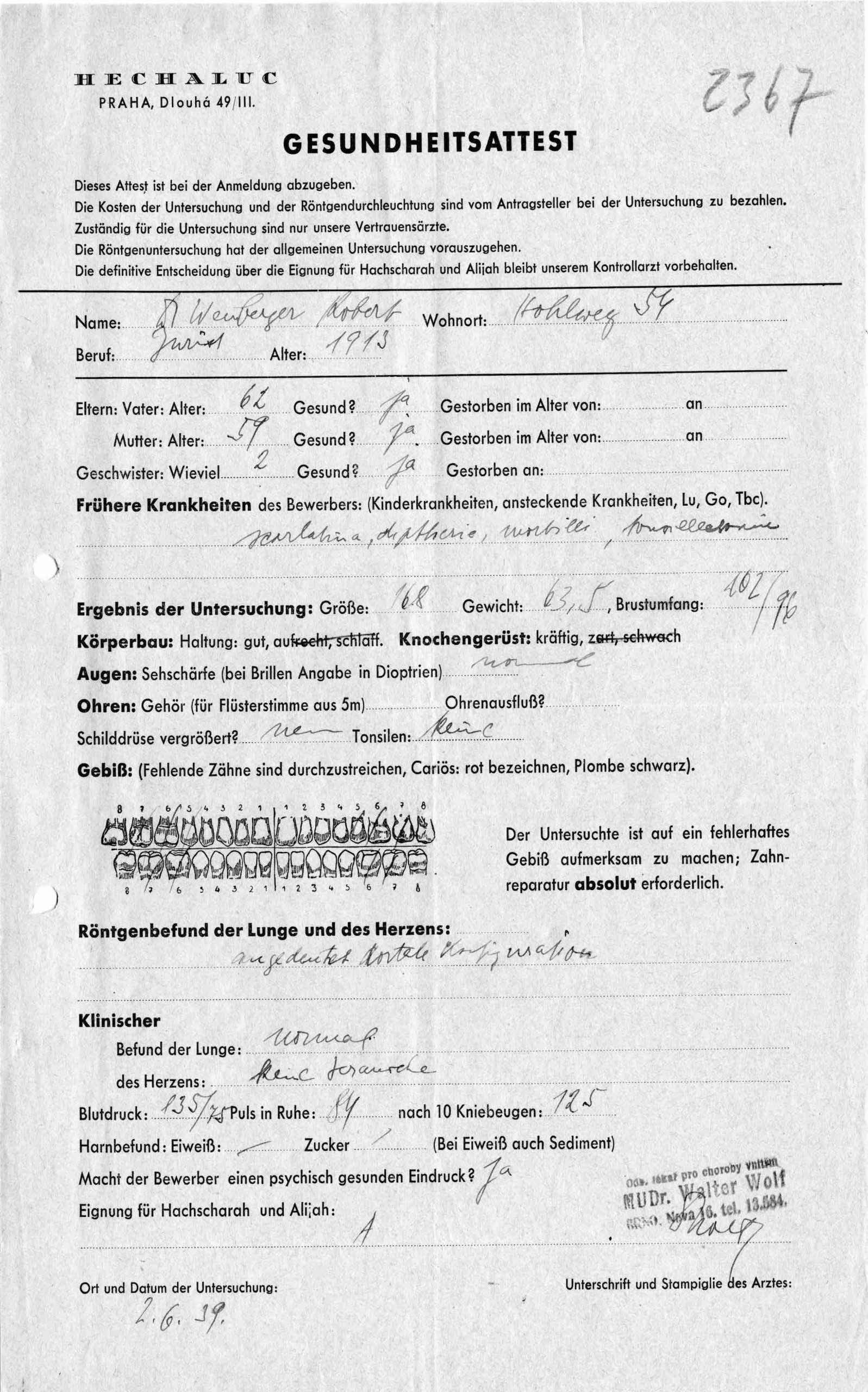

Questionnaire of the Hehalutz office for those interested in Hachshara training, 1939 (Jewish Museum in Prague, Documents of Persecution)

The questionnaire analyzes in detail personal information about each applicant, including his/her health condition. We can find complex questions such as personal questions, knowledge of foreign languages (Hebrew), references on eligibility, a coveted form of employment, financial circumstances of the family, information about relatives. Further, it investigates the medical history of the applicant, including the medical history of his/her family, size, weight, bone structure, dental records, a clinical state with information about blood pressure and pulse, and psychical condition, etc. These questionnaires were submitted to Hehalutz Department for further eligibility assessment of the applicant and enlistment to Hachshara training.

Since the confirmation of completion of the Hachshara training became a prerequisite for obtaining the emigration certificate for the majority of the Jews, the Palestinian Office intensified the organization of vocational training centers and temporarily altered the geography of “Jewish” spaces in the Protectorate. Various agricultural training centers, courses, and professional training camps were established and organized with unprecedented intensity. Because of that, 3 000 Jews managed to emigrate with the help of the Palestinian Office in 1939. There is a lack of statistical data about the emigration in previous years. However, based on the report of Hehalutz, only 109 young people emigrated from Czechoslovakia in 1935.3 Of the 3000 in 1939, 2 654 applicants gained certificates after the foundation of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration, which dealt with matters for the emigration of Jews under the Nazis supervision, 75% of these applicants had little or no financial guarantees, and their emigration was possible due to effective redistribution of the resources only.4

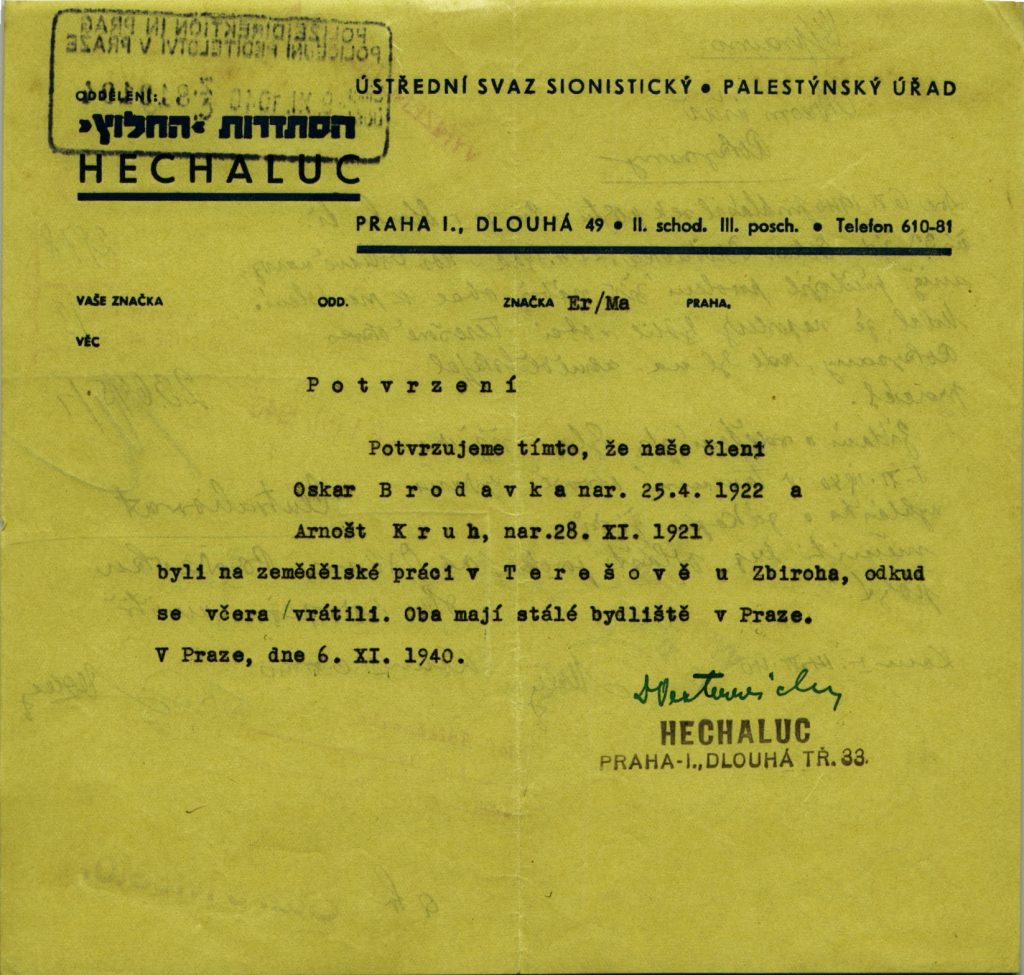

Hachshara training in agriculture, 1940 (Národní archiv, Policejní ředitelství II 1931-1940, sign. B2978/13, kart. 4953, Oskar Brodavka, nar. 25.4,.1922.)

Chances to emigrate became even more limited in the upcoming years. Organization of the vocational training and requalification centers depended on continually changing guidelines. Hehalutz department of the Palestinian Office was responsible for requalification courses for the age group 17-35 years. For this purpose, labor units were organized and trained in newly founded agricultural farms that operated only during the harvest time. These places were mostly farms and manors of Czech farmers, located all over the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Jewish workers replaced the seasonal labor force and supplied the particular demands of farmers; this became a part of the economic exploitation of Jews. While they usually worked for free food and accommodation only, they often encountered antisemitism or various other forms of exploitation from farmers. Mr. H.D., one of the organizers of the Hachshara training camps, described such practice as follows:

“We worked for food only. It began in 1939-40. We had various problems, the Jews never worked in agriculture, there was hard work, and we also had problems from the landlords who did not give us enough food. There were also problems with the fact that Jews were no longer allowed to travel. I had permission to travel once per month, but I traveled every week. After the assassination of Heydrich in 1942, landlords began to fear to employ Jews. I drove from one to the other and asked if they would still employ Jews – they didn’t want to.”5

In some cases, workers also earned some pocket-money. Despite such issues, retraining was promoted and often idealized by Jewish Community leaders.

In order to enable emigration to the other aged groups, several other departments were established. It was the Central Jewish Labor Office (Ústřední židovský úřad práce) for Jewish adults, mostly intellectuals. The Office mediated jobs and organized vocational training.The Jewish Help for Youth Department (Židovská pomoc mladým) dealt with young people between 12-17 years and organized Youth Aliyah training centers for emigration in Prague, Brno, and Vermeřovice.

On May 10, 1941, the Palestinian Office was suddenly dissolved, and emigration certificates have temporarily ceased to be issued with an exception for those who are staying in neutral countries. With the dissolution of the Palestinian office, vocational training as a precondition for obtaining the emigration certificates became worthless.6

At present, it is impossible to determine the location of all retraining centers operating under the Hehalutz department – Hachsharot. Neither can we determine how many Jews underwent vocational training in there, nor can we trace all forms of employment of the Jewish workers. By the end of 1941, when the Nazis halted emigration, there were temporal changes in Jewish geography in Bohemia and Moravia. Younger Jewish population especially was shifted from industrialized urban and metropolitan centers to the countryside where they found themselves in an even more difficult situation and where they learned utterly new skills. Based on the Oral History Collection of the Jewish Museum in Prague, we can locate at least some of the Hachsharot training centers organized in the former territory of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

The spatial patterns on the map show the places where Hachsharot training centers were held, and offer insight to temporal changes of Jewish geography mentioned.

Map of the Hachshara training centers in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (in blue). See fullscreen visualisation of the “Hachshara training centers”.

Mapping the places was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

- Israel Oppenheim, The Struggle of Jewish Youth for Productivization: The Zionist Youth Movement in Poland. East European Monographs, 1989. p. 1-7.

- Krejčová Helena, Svobodová Jana and Hyndráková Anna, Židé v Protektorátu – Hlášení Židovské náboženské obce v roce 1942 (Jews in the Protectorate – A report of the Jewish Religious Community in 1942). Havlíčkův Brod: Maxdorf, 1997, 183-186.

- Čapková, Kateřina, Czechs, Germans, Jews? National Identity and the Jews of Bohemia. New York, Oxford 2012. p. 239

- Krejčová Helena, Svobodová Jana and Hyndráková Anna, Židé v Protektorátu – Hlášení Židovské náboženské obce v roce 1942, p. 185.

- Jewish Museum in Prague, Oral History Collection, tape 504 (H.D.).

- Krejčová Helena, Svobodová Jana and Hyndráková Anna, Židé v Protektorátu – Hlášení Židovské náboženské obce v roce 1942, pp. 116-124, p. 185.