“We were clearing up the ruins of the devastated Warsaw ghetto…While clearing the rubble, we found many dead bodies. Despite the [Germans’] ban, we gave them a burial. Some had knives and weapons in their hands” – remembered 19-year-old Hungarian Jewish survivor, József Davidovics in 1945. Roughly a year after the Warsaw ghetto revolt was oppressed by the SS, Hungarian Jewish deportees were tasked with clearing the immense desert of rubble left after uprising. The remains of thousands of Jews were still buried under the ruins. Davidovics was a prisoner of former Konzentrationslager Warschau, a camp the Nazis set up on the ruins of Europe’s largest ghetto. It was liberated by Polish resistance fighters in the summer of 1944, making KL Warschau the only main camp that was not freed by Allied troops, but members of an anti-Nazi insurgency.

Hungarian testimonies as sources of the KL’s history

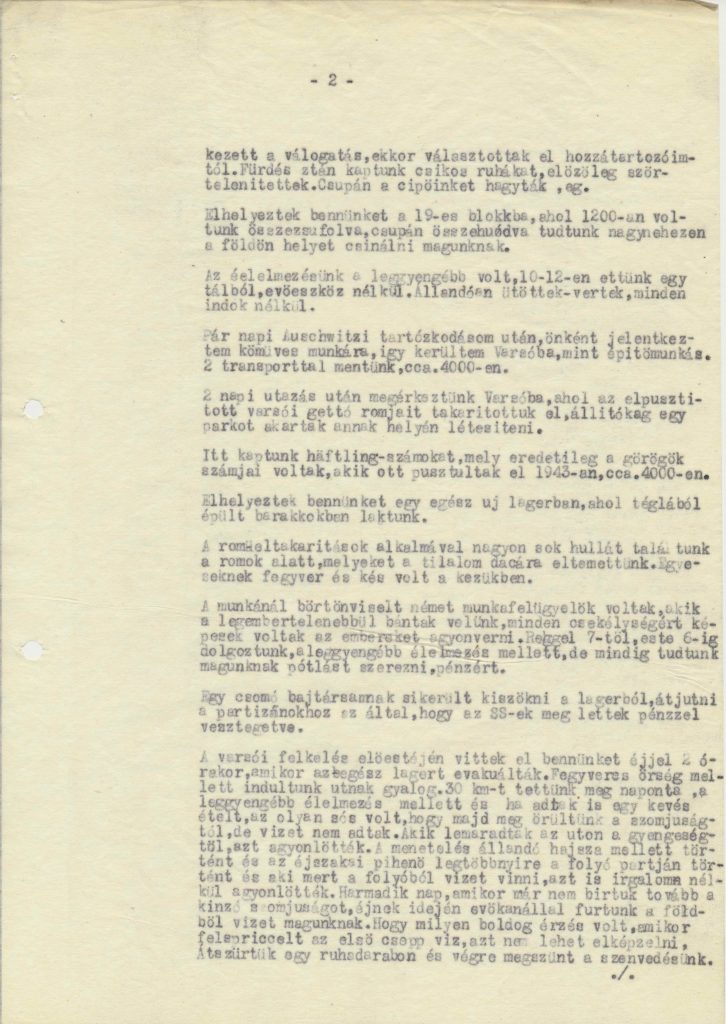

The SS destroyed the majority of relevant documents before evacuating the camp in the summer of 1944. Our knowledge on the KL is therefore rather scarce. Warsaw is another example of a persecution site about which perpetrator documents have hardly remained. Therefore survivor and eyewitness testimonies are crucial if we would like to reconstruct KL Warschau’s history. As most prisoners were Hungarian Jews, the testimony of 60 of the camp’s survivors held by the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives constitute a particularly significant source material. Their analysis offers insight into the camp’s history as well as the fate of people imprisoned in it.

The Warsaw Ghetto

Before the war, Warsaw was home to the second largest Jewish population in the world after New York. After the German occupation, 450,000 people from Warsaw and the neighboring localities were crammed into a ghetto set up by the Nazis, that was closed off with a wall on 15 November 1940. Barely 10,000 of them received enough food. Until the summer of 1942, an average of 3882 people starved to death or died due to epidemics each month.1 These casualties were dwarfed by the so-called Grossaktion Warschau launched on 22 July 1942: in two months the SS deported more than 250,000 Jews into the gas chambers of Treblinka extermination camp. Further thousands were shot on the streets; others starved to death or committed suicide. Only 70,000 to 80,000 inmates stayed in ghetto – mostly young people, fit to work. In February 1943, Reichleader SS Heinrich Himmler ordered the complete demolition of the ghetto. But this time, the SS troops met an unexpected Jewish armed resistance. Hundreds of young Jewish men and women attacked the SS forces entering the ghetto. It took the Germans almost a month to oppress the unprecedented resistance. The Nazis systematically blew up ghetto buildings during the fight. 15,000 to 20,000 Jews were killed in the uprising and a further 56,000 were deported to Treblinka and the work camps around Lublin. On May 16, 1943 SS General Jürgen Stroop was proud to report to Berlin that “there is no longer a Jewish Residential Quarter in Warsaw… With the exception of eight buildings … the former ghetto has been completely demolished”.

KL Warschau

Besides a few thousand people in hiding, no Jews were left in Warsaw after the uprising. In June 1943, Himmler, who already planned to create a concentration camp in the city as early as October 1942, ordered the SS-WVHA (SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt/SS Economic and Administrative Main Office) to set up a camp on the site of the former ghetto. He also ordered the SS to have the rubble cleared, usable building material collected, Jewish hiding places liquidated and a park set up. The plan had a rational element – as the Nazis planned to rule the “East” for a thousand years, it seemed pointless to sustain a vast field of rubble in the middle of a large city in the long run.

KL Warschau officially started its operation on 19 July 1943. As the ghetto area had only a few buildings left, the new camp started run in the former prison complex of the German Sicherheitspolizei in Gęsia (in Polish: goose) Street. (Soon the camp was dubbed as “Gęsiówka”, i.e. “little goose”). Later the camp was extended with two more sections. Twenty barracks were erected built of bricks and wood.

Camp SS

The first camp commander was SS-Obersturmbannführer Wilhelm Göcke. Although he was discharged from the Waffen-SS in 1941 due to a scandal, now he was surprisingly assigned to command KL Warschau. After a few weeks he was redeployed to lead KL Kauen (Kaunas) in Lithuania. His successor in Warsaw, 54-year-old SS Captain Nikolaus Herbet did not have an extensive camp experience either. Indicative of the general lack of cadres, for a while there was no chief physician in the camp and the Political Department (the camp Gestapo) was also operating without a commander. Initially the site was guarded by 150 SS men. Most of them were ethnic Germans from Romania, Yugoslavia and Poland. On average they belonged to the older age cohort – they were born between 1899 and 1921. They were supported by Ukrainian SS men from the Trawniki training camp. The camp’s surroundings and the former ghetto site were patrolled by an SS and police regiment.2

Slave labor, economic failure, corruption

The first 300 prisoners arrived from KL Buchenwald in July 1943. They were German political prisoners and professional criminals. They became the first functionaries – capos, overseers, administrators. According to German estimations, the SS needed 10,000 prisoners to clear the rubble, but the infrastructure, including lodging, was not in place. Therefore until November 1943 only 3683 Jews were transported from KL Auschwitz. After the ghetto revolt, the Nazis did not want prisoners in Warsaw, who knew Polish, were familiar with the place and hence could have been capable of fleeing or getting organized. Hence mainly Greek Jews were sent, but Dutch and French prisoners also arrived and eventually a few Poles as well. From a Nazi point of view, the history of KL Warschau proved to be an economic and administrative disaster. The rubble clearing and the erection of the ghetto were delayed. As there was no proper water supply and the prisoners could not wash themselves, a typhoid fever epidemic broke out and decimated the inmates. By March 1944, 75 percent of the prisoners had died and the camp had to be quarantined.3 The SS had to hire thousands of Polish workers instead of using free Jewish slave labor. It was almost a year before the SS-WVHA could report that the camp would be soon completed in the summer of 1944. According to SS data, 34 million bricks, 1300 tons of iron ore, 6000 tons of scrap metal and 805 tons of other metals were collected from the ghetto rubble. The seemingly impressive numbers covered a disappointing reality: the extraction of the building material worth of 5 million Marks and the erection of the camp cost 30 times as much, 150 million Marks.4 Moreover, an SS-WVHA investigation revealed cases of serious corruption in KL Warschau. It became clear that the SS leaders not only sold the prisoners’ underwear on the black market, but – together with the prisoner functionaries – they also plundered the inmates and stole the valuables found beneath the ghetto ruins. Commander Herbet and others were arrested and interned in KL Sachsenhausen. Parallel to these events, KL Warschau lost its independence and became a sub-camp subordinated to KL Lublin (Majdanek) as “Arbeitslager Warschau”. New guards and the new commander, SS-Obersturmführer Friedrich Wilhelm Ruppert, were redeployed from Majdanek. He became the last commander of the camp.

Hungarian Jewish transports

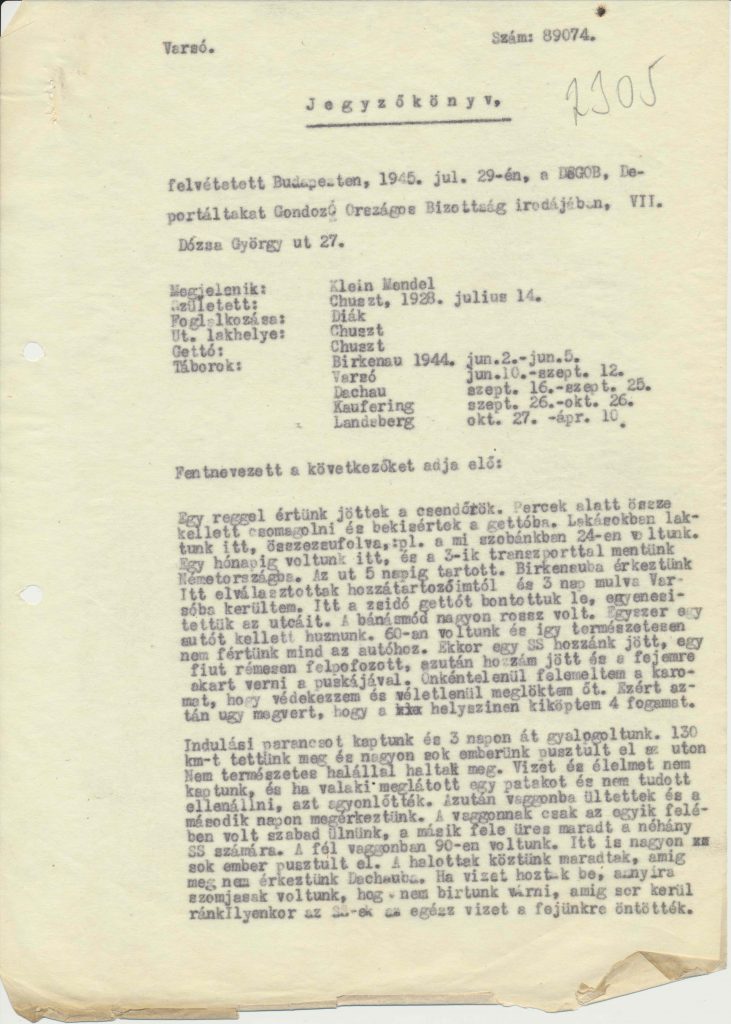

Restructuring the camp’s operation and replacing the commander had not solved the most crippling issue: the lack of workforce. To remedy this, as of May 1944, the SS deported thousands of Hungarian Jewish men to Warsaw from Auschwitz-Birkenau. No documentation pertaining to these transports survived. The lack of German documents raises the significance of the testimonies of dozens of survivors taken in Budapest in 1945 by the National Committee for Attending Deportees (Deportáltakat Gondozó Országos Bizottság – DEGOB), a Hungarian Jewish relief organization.

The analysis of these testimonies provides a meaningful amount of information regarding the Hungarian Jews arriving in Warsaw. Most of them were deported in late May 1944 by the Hungarian authorities from the ghettoes of Munkács, Huszt, Técső, Ungvár in Carpatho-Ruthenia (today: Ukraine) to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Others were taken from Eastern Hungarian cities, such as Mátészalka. Typically they arrived in Birkenau after three days of travel. Those from Carpatho-Ruthenia were selected by Dr. Mengele, while the Mátészalka transport was received by SS-Rapportführer (Roll Call Leader), Oswald Kaduk, who was later sentenced to life in the so-called Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt.5 Those deemed unfit to work were murdered in the gas chambers immediately. The ones capable of working were taken to sections BIIc, BIId and BIIe of Birkenau. Here they spent 3 to 10 days in average. The oldest among them was born in 1890, the youngest in 1930. Most them were 15 to 25 years old: teenagers and young men. They were not registered in Auschwitz therefore they were not tattooed with prisoner numbers either.

The number of Hungarian Jews transported from Auschwitz to Warsaw is unclear. The literature’s estimates vary from 2500 to 5000.6 However, it is certain that they constituted the most populous prisoner group of KL Warschau.

The analysis of DEGOB protocols suggests that at least two transports carried them from Birkenau and their number was around 4000. According József Davidovics (mentioned earlier) “we went with two transports, ca. 4000 of us”.7 The accuracy of his testimony is supported by other Hungarian survivors as well and an account by a Polish Jew also confirms that the first, 2000-strong Hungarian groups arrived in KL Warschau at the end of May 1944.8

Conditions, rations

Under the new SS leadership deployed from KL Lublin, the general conditions somewhat improved. Most Hungarian survivors remembered founding themselves in a more favorable situation than Birkenau. They were accommodated in brick barracks that housed 160 to 250 prisoners. According to a boy from Munkács, „everybody has his own bed to sleep in and an extra rug to cover with. … It was heavenly compared to … Auschwitz.”9 Another prisoner remembered as follows: “We lived in a relatively clean camp. We received [clean] underwear every fourth day. Food supply was satisfactory. We received white bread on more than one occasion.”10 According to other testimonies, the prisoners received 50 decagrams of bread and 0.75 liters of soup twice a day. Rations in other commandos (working group) were far from this: “the only thing they gave us to eat was carrots” – complained a survivor from Budapest.

After the ghetto revolt: executions, cremations

As the Nazis were suspicious that Polish prisoners – who spoke the local language – would try to escape, they preferred sending Hungarians to external workplaces. Ferdinand Wald and 150 other prisoners were assigned for deforestation works. Another Hungarian team worked at the building of the new crematorium which “was completed when we left the site”.11 Most Hungarian Jews toiled away among the ruins of the ghetto and collected bricks, stone, and iron beams. They were ordered to clean 250 bricks per day per person.12 One of the commandos shoveled rubble 12 hours a day in the ghetto, even when they were sick and had 40-degree fever. However, other Hungarians were engaged in burning corpses found in the ghetto: “Once we cremated the corpses of 240 people. They piled the bodies up, poured gasoline over it and then set the pile on fire. In 10 minutes the whole cremation was over. We loaded the firewood, the Poles piled up the corpses and ignited them.”13 Others witnessed the murder of Jews who had been hiding among the ruins for a year. Henrik Stein and other prisoners “dug up the ground and many times they found Jewish families who for years lived in these narrow underground cellars. They were immediately executed [by the SS].”14

Treatment

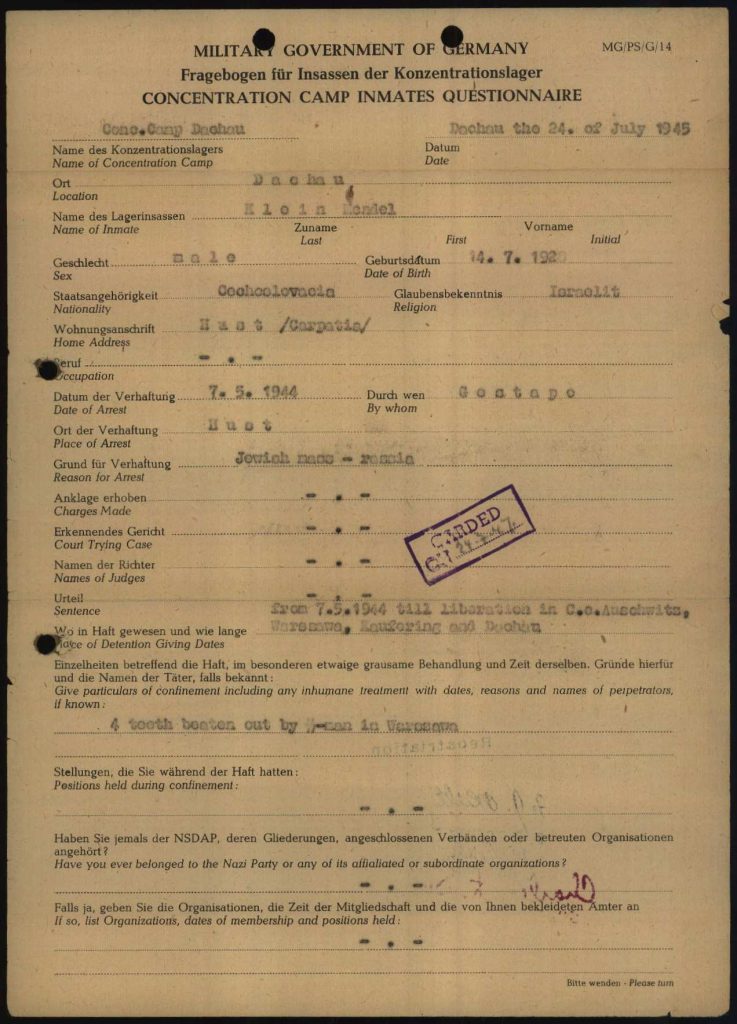

Prisoners were regularly beaten. German capos were especially brutal. “Our overseers were German Aryans, mainly criminals who would beat uswithout any particular reason” – remembered a Hungarian Jew. According to a 14-year-old boy from Munkács, they were even worse than the SS: “The guards treated us well, but there were German prisoners, robbers and murderers, the so-called green triangles, who were functionaries which meant they did with us whatever they wanted; they kept beating us up as they pleased.” Other Hungarian Jews gave account of SS brutality: “They set the dogs on us and these tore chunks of flesh out of our legs. I still carry the mark caused by a dog like this biting my thigh” –remembered a 50-year-old survivor.15 Sixteen-year-old Mendel Klein suffered the most brutal beating of his life in Warsaw: “Once we had to pull a car. There were 60 of us so obviously all of us couldn’t get to the car. Up came an SS and slapped a boy and then he came up to me and wanted to hit my head with his rifle. As a reflex I defended my head with my arm and I pushed him by accident. So he beat me up so badly that I spat out four of my teeth right on the spot.”16 He reported the incident to the US authorities after the war as well.

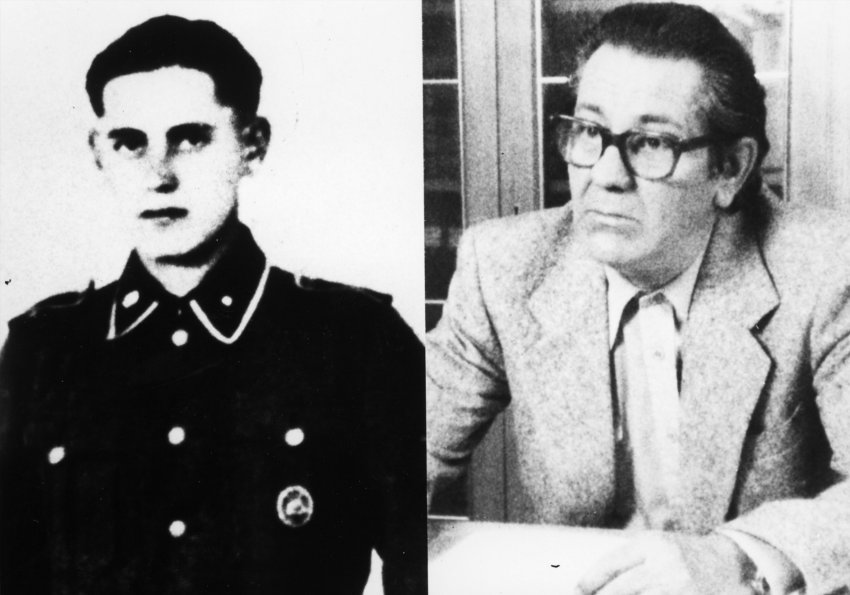

Mátyás Teichmann, a bookbinder from Alsóverecke remembered that the name of the most brutal SS was “a Lagerführer, named Omschwitz, who treated us very badly”.17 Most probably he thought of 23-year-old Schutzhaftlagerführer Heinz Villain, who the prisoners called “Umschmitz”.

Corruption and escape

Though the SS-WVHA changed the leadership of the camp, the level of corruption remained the same in the summer of 1944. Polish and German capos sold bread for gold teeth and jewelry. Many Hungarian Jews took valuables they dug out from the ghetto ruins to the black market.18 Capos plundered discovered Jewish hiding places in the ghetto and they robbed the prisoners as well.19 Corruption was part of the everyday operation in Warsaw and its level was even higher than in many other camps: the prisoners could even buy their freedom. Inmates from József Davidovics’s group “managed to escape from the camp and to join the partisans by bribing the SS”. Prisoner escape was not infrequent. 15-year-old Henrik Stern from Huszt worked with Polish Jews. Many of them escaped. The SS threatened with mass retribution and declared that “they will execute ten Jews for every escapee”.20

Evacuation of the camp

As the Red Army was fast approaching, the Warsaw camp’s evacuation was launched at the end of July 1944. The SS asked the prisoners if they felt fit for a 120-kilometer march. Those who said no stayed in the camp with the sick prisoners. A working group of a few hundred men also stayed here under the supervision of 90 SS guards. Their task was to cover the traces. The others, ca. 4000-4500 prisoners, were marched towards Kutno. Before evacuation, the prisoners saw that “the SS destroyed all the documents of the camp”. According to survivors Ernő Roth and Salamon Weisz, those left behind were taken to the camp hospital and “as we later heard, the Transportführer stepped up to their beds and shot everyone”. A survivor from Munkács knew from hearsay that 270 people stayed in the camp hospital: “the sick were given an injection and then they were cremated”. According to another witness, a Hungarian physicians later told him that they saw with their own eyes that 500 prisoners who were unfit to march, “were shot dead together with the sick”. Another prisoner stated that when they set off towards Kutno, the total number of prisoners was 500-600, including the cleaning commando and the sick. Later he received contradictory news about their fate. Some said they had been killed and incinerated, others told him the prisoners in the camp were liberated.21

Both versions were correct. Experienced Polish prisoners warned the Hungarians not to trust the SS’s promise as those left behind would be most probably murdered. It was in vain – ca. 180 Hungarians did not feel strong enough to walk. Soon after the column left the camp, “Umschmitz” and another SS (dubbed by the inmates as “the Gypsy”) shot them and the sick in the head. The corpses were cremated on the former ghetto site by a group of prisoners.22

Liberation

On 1 August 1944, the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), the underground military organization of the Polish Government-in-Exile, launched the Warsaw uprising against the Nazi rule. On the first day, resistance fighters liberated 50 to 70 Hungarian and Greek Jews who worked in the SS warehouse of the so-called Umschlagplatz – a symbolic site from where more than 250,000 Warsaw Jews had been deported to the gas chambers of Treblinka. Four days later, one of the units of the Home Army’s “Zośka” battalion broke through the gate of the Warsaw camp with a captured German Panther tank. In the 90-minute shoot-out some of the SS and SD guards were killed, the rest escaped. In total, 348 Hungarian, Greek and Polish Jews were liberated, some women among them. Thus Warsaw became the only (former) Konzentrationslager liberated by anti-Nazi resistance fighters.

Hungarian Jews in the Warsaw uprising

200 to 250 of the liberated prisoners were Hungarian Jews. Most of them joined the resistance. They were “drawn up military-style in two long ranks…and one of them came to me and saluted ‘Sir…the Jewish Battalion ready for action’ ” – reported Wacław Micuta, one of the Polish commanding officer. “Many died in combat. Our losses were horrendous. But those soldier-Jews left behind them the reputation of exceptionally brave, ingenious and faithful people.” Later Micuta said that the Jews “were fighting like mad, I think three of them survived.”23 Another Polish fighter recalled: “When we finally entered, I saw an amazing thing: a large group of Jews speaking different languages such as Hungarian and French… There was a huge joy… Some of them joined our unit… They took up arms against the Germans with us.”24

In most cases we only know the first names or nicknames of the Hungarian Jews who joined the resistance. One of them, named Kuba, and a Polish corporal fixed a broken canon under the fire of the SS and chased away the Germans by shooting at them with the weapon. On 16 August Kuba and his comrades were conducting a diversion attack among the ghetto ruins while resistance fighters were smuggling ammunition through the sewage system to a cut off Polishunit. Kuba was killed mid-September while fighting for the Czerniaków bridge head. Two other Hungarian Jews, Koloman (maybe Kálmán) and Tibor also died here. This is where another Hungarian Jew, Pawel (probably Pál) died too – he was a member of the “Parasol” battalion and he destroyed German tanks and armored vehicles. On 22 September, when his unit was encircled by Germans, Pawel, who spoke good German, was sent to approach the German lines as an envoy. He was accompanied by another probably Hungarian Jew, a certain Dr. Turek (maybe Török). The Nazis shot both of them.25 Hungarian Jews without a military training also contributed to the resistance efforts. They built barricades, serves as couriers and carried ammunition. They were highly visible targets in their striped uniforms, therefore many was killed. Fifty-four-year Lázár Einhorn from Técső was working on the Umschlagplatz on 1 August under SS supervision. After completing their work there, the Germans drove the prisoners on trucks towards the Danziger Railway Station. On Wildstrasse the resistance ambushed the convoy and freed the prisoners. Glück and other Jews from his unit joined their ranks. For two months they build barricades and buried the dead; other times they carried water in the midst of air raids and shelling. After the defeat, posing as Polish civilians, they were captured again. They survived the war in a labor camp under disguise.26

Keeping the camouflage of not being Jewish was necessary as the SS was constantly combing through the masses of prisoners in search for Jews. “Their first action was to separate the Jews from everyone else. It was easy for them as we were all wearing prisoner uniforms. I have no idea what happened to the others and who survived this. I don’t know anything about my brother either who was separated from me. As for me, as we walked in front of the hospital, I stepped into the building, found a doctor’s coat which covered my prisoner uniform; thus I was put into a cattle car with the other Poles and taken westward” – reported a Hungarian survivor in 1945.27

Ca. 200 of KL Warschau’s former prisoners were still alive when the uprising was put down.28 Most of them – many Hungarians among their ranks – were executed by the SS.

Death march and death train

Most of the 4000-4500 prisoners taken from the Warsaw camp towards Kutno were Hungarians. According to survivor testimonies, the SS forced them to march for 3-4 days in the scorching summer heat. The prisoners were not given food or water. “If someone leaned over to get some water from the ditch or the puddles, the SS shot them. Many people died like this – a lot of them were from Munkács…”29 At least 200 prisoners were murdered – some testimonies estimate an even higher number. Many accounts mention a mass execution at a river crossing, when first the prisoners were allowed to drink from the water, but soon SS men started to hurry them to carry on marching and eventually opened fire on the prisoners:30 “Voraciously we started to drink, but the SS set off his dog on us and ordered us to come out. Meanwhile he also shot someone – he was still alive when the SS made his dog get into the water and the animal mangled the dying prisoner’s throat” – remembered two survivors.31

After days of marching, they arrived at a train. 90 to 110 prisoners were crammed into each cattle car, but half or more of the space in the cars was taken up by the SS and the capos. The prisoners literally laid on each other in the unbearable heat. Only one bucket of water was placed in each car. Handing out water portions, understandably, led to stampedes. “Everyone jumped up so they wouldn’t miss the water, but the guards started the beating and slapping. Many people were beaten to death” – remembered 19-year-old Salamon Junger after the war.32 In other train cars the SS opened fire. The Farkas brothers were crammed into a car with 110 other prisoners. Many of them lost their minds because of the thirst. The guards immediately shot them. Others were so desperate that they broke out the golden teeth from their mouths in exchange for a glass of water. The SS took a whole barrel of water into another car and started to sell it publicly for gold. In Jenő Majrovits’s car the SS simply murdered those with golden teeth.33

The prisoners arrived at Dachau on the fifth day of the journey, on 6 August. Only 3863 survived out of the original transport of 4000-4500. The death march and the train ride therefore claimed hundreds of lives. The survivors arrived in such a dire state that they had to be taken to the hospital immediately. The outraged commander of KL Dachau, Eduard Weiter, filed a complaint against Alfred Kramer, the SS NCO in charge of the transport.34 In total, the Nazis deported 8,000-9,000 people to the Warsaw concentration camp. Estimations vary between 3400 and 5000 as to how many of them died there.This number includes the direct victims of the camp as well as those murdered during the evacuation and the Warsaw uprising. The analysis of the DEGOB protocols allows us to reconstruct the fate of Hungarian Jews deported to the camp. The dozens of testimonies offer a kaleidoscope-like, fragmented, yet insightful picture of major events of the camp’s history as well – the evacuation and liberation by the Polish resistance.

Notes

- For monthly death figures see Jeremy Noakes-Geoffrey Pridham (edited by): Nazism 1919-1945. Vol. 3. Foreign Policy, War and Racial Extermination. University of Exeter Press, Exeter, 1995, p. 1070. ↩

- For further information on Camp SS see Andreas Mix: Warschau – Stammlager. In Wolfgang Benz-Barbara Distel (herausgegeben von): Der Ort des Terrors. Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, Band 8. C. H. Beck, München, 2008, pp. 91, 105-106. ↩

- Gabriel N. Finder: Warschau Main Camp. In Geoffrey P. Megargee (volume editor): Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945. Early Camps, Youth Camps and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum-Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2009. Vol I, p. 1513. ↩

- Andreas Mix 2008, p. 99. ↩

- See the testimonies of Munkács deportee Mátyás Teichmann and József Fischer József, as well as the testimony of Mátészalka deportee Jakab Berger Jakab. 21 July 1945, 2 August 1945, and 21 June 1945, respectively. Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives, DEGOB, (henceforth: HJMA DEGOB) Protocols no. 1009, 2648 and 69. ↩

- According to Finder their number was 4,000 to 5,000. Mix’s estimate is lower: 2500 prisoners. Polish researcher Bogusław Kopka suggests that 3000 Hungarians arrived. In Bogusław Kopka: Das KZ-Warschau. Gesichte und Nachwirkungen. Warszawa, 2010, p. 80. ↩

- Testimony of József Davidovics. 6 October 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 3200. ↩

- See the following testimonies: HJMA DEGOB Nándor Salamon Protocol no. 2872, Sámuel Hochmann Protocol no. 1732, Salamon Lebovits Protocol no. 2543, Mendel Klein Protocol no. 2305. Also see Bericht des Oskar Paserman (1947. Oktober 14.) quoted by Kopka 2010, p. 111. ↩

- Testimony of Desiderius Weingarten. 28 July 2945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 2952. ↩

- Testimony of József Farkas. 15 August 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol 1612. ↩

- Testimony of Sámuel Hochman. 19 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 1732. ↩

- Testimony of Salamon Lebovits. 2 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 2543. ↩

- Testimony of Salamon Basch. 12 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 1221. ↩

- Testimony of Henrik Stern. 12 August 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 2917. ↩

- See the following testimonies in HJMA DEGOB: József Fischer József, Protocol no. 2648; Nándor Salamon, Protocol no. 2872; Izrael Szmulovits, Protocol no. 3353; Mózes Friedmann, Protocol no. 3367. ↩

- Testimony of Mendel Klein. 29 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 2305. ↩

- Testimony of Mátyás Teichmann. 21 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 1009. ↩

- Testimonies of Ernő and József Rath. 24 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, 2368. ↩

- Testimonies of Ernő Roth and Salamon Weisz Salamon. 11 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, 1132. ↩

- Testimony of József Davidovics József. 6 October 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 3200 and testimony of Henrik Stern. 12 August 1945. HJMA DEGOB, 2917. ↩

- For the events following the evacuation, see: Ernő Róth and Salamon Weisz, Protocol no. 1132; Nándor Salamon, Protocol no. 2872; Ferdinánd Wald, Protocol no. 3069; Izrael Szmulovits, Protocol no. 3353. ↩

- See for example Kopka 2010, p. 113. ↩

- The report quoted by: http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/othercamps/gesiowka.html. See also Micuta’s interview in a CNN documentary “Warsaw Rising – The Forgotten Soldiers of WWII” from 15:29, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7EvPXStuqlc. ↩

- Quoted in Joshua D. Zimmerman: The Polish Underground and the Jews 1939-1945. Cambridge University Press, New York, 2015, p. 390. Also see the original oral history interview with Juliusz Bogdan Deczkowski. June 25 1991. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum1991.A.0113.3, RG Number: RG-50.059.0003. ↩

- See for instance a testimony published under the title “Die letztenTage von Czerniaków” by the Warsaw Uprising Remembrance Association: http://www.sppw1944.org/index.html?http://www.sppw1944.org/powstanie/czerniakow_koniec_ger.html. Also see a summary by Edward Kossoy titled as “The Gęsiówka Story: A Little Known Page of Jewish Fighting History” at https://gesiowka.adactio.com/#The%20G%C4%99si%C3%B3wka%20Story%3A%0D%0AA%20Little%20Known%20Page%20of%20Jewish%20Fighting%20History ↩

- Testimony of Lázár Einhorn. 31 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no.1237. ↩

- Testimony of Jenő Sternthal. 3 April 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 3637. See also the testimony of Desiderius Weingarten. 28 July 2945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 2952. ↩

- Testimony of Lázár Einhorn. 31 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 1237. ↩

- Testimonies of Ernő Roth and Salamon Weisz. 11 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol 1132. ↩

- Ibid, see also testimony of Ernő Glück. 23 June 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 90. ↩

- Testimonies of Ernő Roth and Salamon Weisz. 11 July 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol 1132. ↩

- Testimony of Salamon Junger.3 August 1945. HJMA DEGOB, Protocol no. 2398. ↩

- See for example the testimonies of Simon and Izsák Farkas, Protocol no. 1515; Ernő Glück, Protocol no. 90; Jenő Majrovits, Protocol 2852. ↩

- Andreas Mix 2008, p. 113. ↩