“When we returned to Luxembourg, our native country, we got off the train and went to the school building. We had no identification and a person wrote down in our papers Jew and Polish because my parents came from Poland. They had come years ago but they had never taken Luxembourgish citizenship. […] They did not offer us anything – no food, nothing – and my mother cried. They only offered us a sandwich and we said no thank you… then we crossed a bridge to the new town and people were staring at us. […] I went to our neighbour Marcel and he looked at me like a ghost. Nobody thought that we would ever come back. Only in Luxembourg, where I spent my youth, did I have such a terrible experience. In Belgium, they were waiting for us with baskets of food.”1

Mapping the places was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

Who is guilty? Germans or Luxembourgers?

As a result of statements such as the one above, as well as a number of initiatives, Luxembourgish state policy before the war has come under the scrutiny of historians in recent years. The aim to undertake further profound analysis of the mentioned issue was quite simple either approve or disapprove the statements of Holocaust survivors, war victims, journalists and politicians. Many similar initiatives have been launched in the Benelux states, with a variety of outcomes.

In September 2012, Belgian Prime Minister Elio di Rupo officially apologised to the Jewish community in his country for the attitude of the Belgian administration during the war. Following this gesture, the historian and former curator of the National Archives of Luxembourg (ANLux), Serge Hoffmann, published an open letter in which he asked Jean-Claude Juncker, the then Luxembourgish Prime Minister, if a similar gesture would not also have been appropriate from the Luxembourg Government. In late September 2012, Ben Fayot2, a political historian officially appealed to the Prime Minister to decide on this issue. In his response, Juncker noted certain misconceptions and discrepancies in Luxembourg’s role in this historical period and confirmed the need to set up an independent commission of historians to examine the issue. The outcome was a report entitled La collaboration au Luxembourg durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale (1940-1945), commonly known as the Artuso report.

This report came to the conclusion that the Luxembourg state administrative deliberately supported and collaborated with the Nazi regime. Luxembourg journalist Paul Cerf was the first to uncover collaboration by several members of Luxembourgish elites with Nazi Germany. However he never went so far as to condemn the Luxembourg state administration for adopting specific anti-Semitic policy measures with the Nazi civil administration. In 2001, he even wrote: “All measures against the Jews, from spoliation to segregation and acts of humiliation, from intolerable harassment to deportation, were entirely the work of the Germans. No Luxembourgers were directly involved.”3

As a follow-up to these initiatives, historian Denis Scuto, a professor at the University of Luxembourg, launched a new project, LUXSTAPOJE, to continue the research. The aim of the project is to systematise and extend the analysis of individual records held by the Luxembourg “Foreign Police” (Fremdenpolizei). It endeavours to link macro-historical studies with micro-historical or prosopographic studies on the Holocaust in Luxembourg. It focuses on a specific group of people who lived in a specific territory, i.e. foreign Jews who lived in Luxembourg in the late 1930s. Since September 2016, the LUXSTAPOJE project team was completed by researchers Marc Gloden, Vincent Artuso, a master’s student, Paul Fonck, and two PhD students Jakub Bronec and Narveen Kaur and Marten Düring, a researcher specialized in the network analysis. We altogether set the database containing information derived from individual folders.

Having consulted individual records held by the Foreign Police, sources which were often ignored by previous Holocaust researchers, we invested a great deal of effort to trace the fates of Jewish immigrants from 1930 to 1950. The post-war period was a unique political environment for assimilation into Luxembourgish society. The project maps the destiny of Jews trying to restore their presence and existence in Luxembourg.

Individual records as a family chronicle

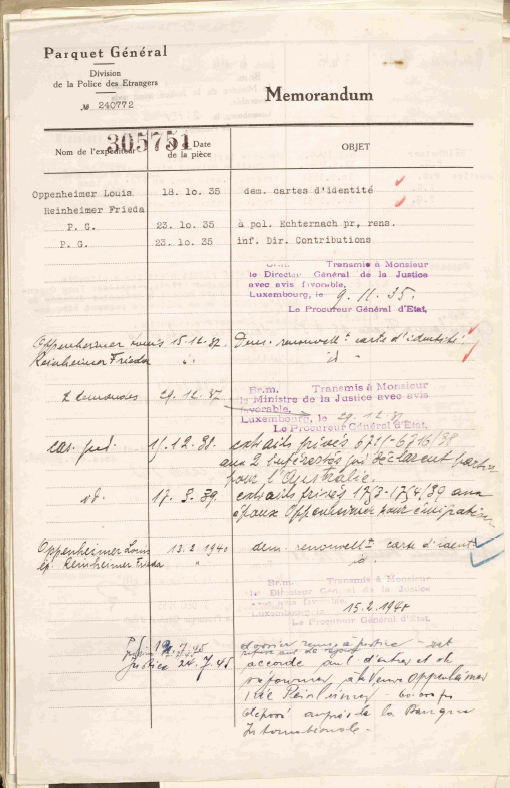

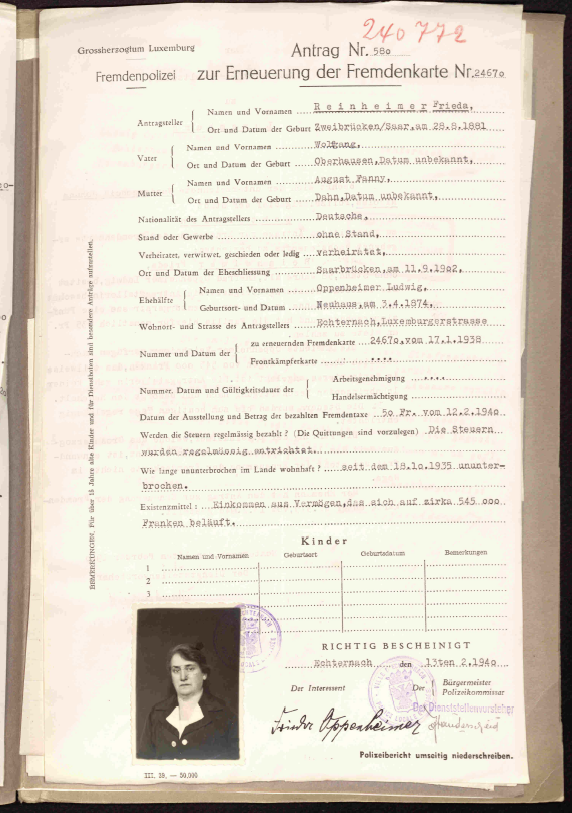

Foreign Police records are stored in the National Archives in the Ministry of Justice collection. Each record contains a memorandum indicating the significant dates in chronological order and the declaration of arrival, which was compulsory for all foreigners over 15 years old. The records also contain many other confidential documents such as applications to renew ID cards: these forms emerged in 1936, when the first ID cards had to be renewed.

Researchers can also find valuable information in the Foreign Police reports on those who wanted to extend their stay in Luxembourg and apply for a new ID card. These reports were the first stage in the bureaucratic process to obtain the coveted permission from Luxembourgish authorities. People who intended to apply for repatriation after the war then had to complete a long and detailed questionnaire about their relationship with Luxembourg, their physical and mental health and lastly but importantly their financial situation.

| Population ratio (LUX) | 1930 | 1935 | Variations (%) |

| Foreign Jews | 1,526 | 2,274 | + 49.0% |

| Luxembourgish Jews | 716 | 870 | + 21.5% |

| Jews | 2,242 | 3,144 | + 40.2% |

| Foreign population | 55,831 | 38,369 | – 31.3% |

| Luxembourgish population | 244,162 | 258,544 | + 5.9% |

| Total population | 299,993 | 296,913 | – 1.0% |

The third stage was at the Ministry of Justice, which had the task of examining all applications submitted by both individuals and state authorities. In the event of a positive decision, the applicant received an official letter signed by a Government Adviser, then a Luxembourgish ID card. Negative decisions issued by the Ministry of Justice indicated that the identity card had been rejected. These decisions involved consulting the Public Prosecutor’s Office to determine the deadline granted to each immigrant for leaving Luxembourgish territory. From 1938 onward, the Ministry of Justice often dealt with urgent applications from Jews wanting to unite their families stranded in Germany or in Austria.

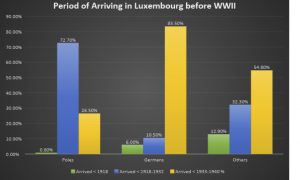

Before the conflict, mainly young men managed to escape from occupied Luxembourg. German male Jews fled to Belgium and France in most cases, so the deportations primarily affected the female Jewish population. German and Luxembourgish Jews were lucky in a way since they were deported to the Litzmannstadt and Theresienstadt ghettos, which slightly increased their chances of survival in comparison with those (mostly Polish Jews) who were deported to extermination camps in Poland. We can make two observations: first, deportation affected all Jews, regardless of when they arrived in Luxembourg. Second, the Jews who arrived in the 1920s and late 1930s became more often the target of deportations than other foreigners 46.7% (39.8%) who arrived within the same time.

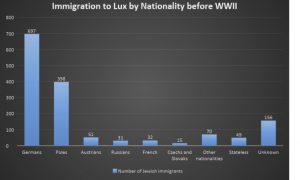

As reported in the graphs below, the highest number of immigrants came to Luxembourg from Germany, especially after the Nazis came into power. Luxembourg also became the final destinations for Polish economic refugees who sought to find occupations and save space for their families in Western Europe. Jews arrived to Luxembourg from different reasons and various motivations but their aim was the same – to find a new homeland to restart their lives. However, in most cases they only found “tolerance to be tolerated” and life in uncertainty.

The application for the ID card listed above contains detailed information about individual applicants as well as personal data about their family members, e.g. parents, spouse and children. One section which is particularly useful for social network analysis is the information about the applicant’s previous stays and movements. There are also details about the applicant’s tax paying morality, occupation and salary, as well as data concerning children under the age of 15.

Foreign Police records provide a great deal of information about foreigners who used to live in Luxembourg, enabling us to examine a number of intriguing questions. These documents shed light on the socio-economic profiles of Jewish refugees over time and compare them with other groups of immigrants seeking asylum in Luxembourg. They also provide information about the attitude of the authorities towards a particular group of immigrants and the decision-making process with regard to individuals. By combining various angles, we can study the impact of this approach on the composition of the immigrant population. Last but not least, we were able to find out about the role of other associations defending Jewish refugees (such as the ESRA Jewish social welfare organisation).

Memos for exceptional cases

LUXSTAPOJE team create a number of detailed portraits to reflect the specific situations of newcomers. Detailed information was taken primarily from Foreign Police reports and the memorandums containing the schedule and timeframe of each administrative process. Here are a few portraits of newcomers based on the archival documentation illustrating their desperate situation.

“Samuel Schwarzmacher and Esther Rywka arrived in Luxembourg from Belgium in 1926. Upon arrival, neither of them presented a passport. Esther had a family record book and Schwarzmacher had his ID card. While Esther took care of the housework, her husband made a living in unstable occupations. He first worked as a steelworker before being dismissed in the early 1930s. Then he found a job as a furrier in Grünstein and the couple moved to Luxembourg City. After 1938 Schwarzmacher ended up in a situation of virtual unemployment. During the summer season, he sold sweets at city markets. Despite these efforts, the authorities stated that the couple was not eligible for state social support and assistance. Eventually they were granted funding from ESRA.”4

“Mr Bloch married Zelenka on 15 July 1938, hoping to bring her to his homeland (France). Since Zelenka’s application for immigration was rejected because only a religious marriage ceremony had been held, the couple came to Luxembourg, where they contracted a civil marriage. After that, they tried to emigrate either to France or to Czechoslovakia. According to Zelenka, the marriage would have allowed them to obtain Czechoslovak citizenship. Both were able to prove the endorsement by the Jewish association ESRA.”5

The fate of these couples indicates the desperate situation of long-term immigrants who had no guarantee of staying in the country until they had acquired Luxembourg nationality. Any travel incidents, economic issues or family problems could thwart their permission to stay in Luxembourg.

The standardised questionnaire included personal questions, especially section V (Nähere angaben über Lohn oder sonstiges Einkommen) about the applicant’s financial situation. Applicants had to declare all direct or indirect income and family fortune occupied in

commercial papers. Moreover, people were asked to provide proof of their mental and physical ability to request permanent residency or repatriation.

Decisions by Luxembourgish authorities about postwar repatriation

Once the Nazis had been expelled from Luxembourg by the Allied forces, more than 300 surviving Jews made an official request to return to their homeland, where they had left behind most of their belongings and friends.

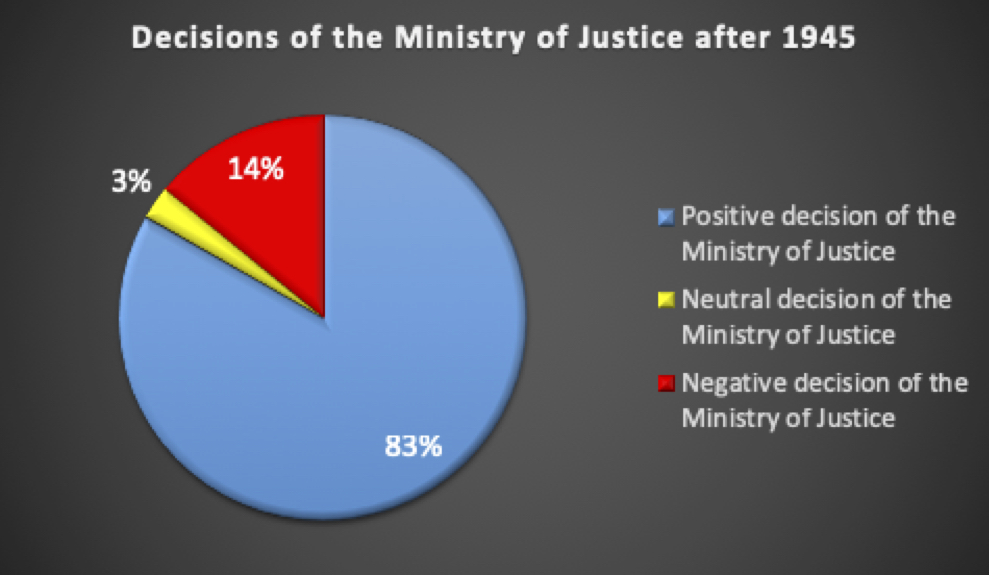

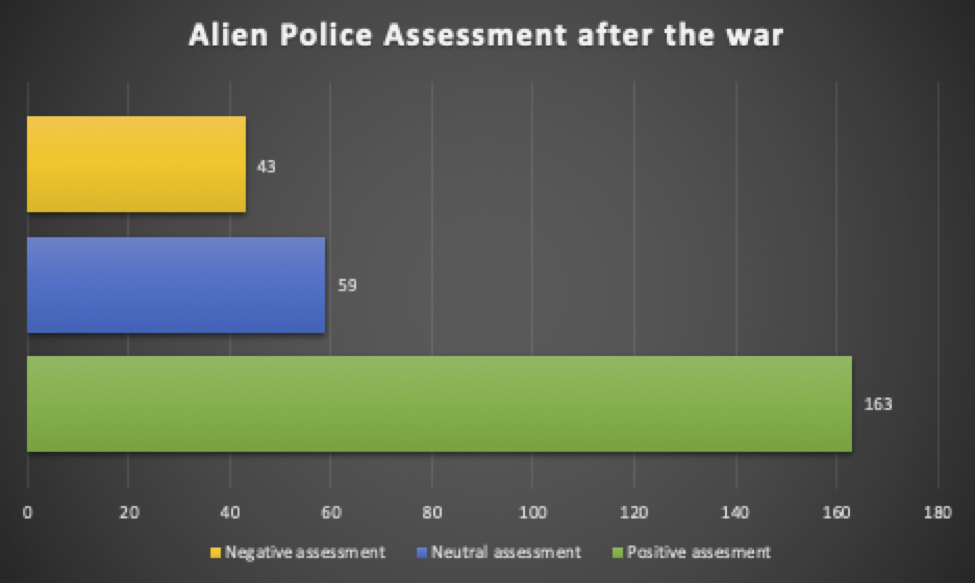

Despite living in often impoverished and indigent conditions, all applicants had to undergo a lengthy bureaucratic process that often lasted a few years. During that time, many people decided to withdraw their applications once they found out that they would not be processed. Those who were patient enough had to complete forms similar to those requested in the 1930-40s and their application moved up to a special committee established by Ministry of Justice which considered submitted reasons of returnees . Despite the fact that most applications were approved, LUXSTAPOJE team stumbled upon a few that were unfairly rejected by the Ministry of Justice (see statistics below). The team investigated the Government Advisers that signed these rejections but were unable to reveal any particular motives or patterns in their decisions. Sometimes applications were rejected without any particular reasons. It seems that the double citizenship or stateless were big obstacles in the bureaucratic process to obtain the Luxembourgish citizenship after the war. However the Ministry of Justice appeared to be less stern than the Alien Police. It often occurred it issued the residence permit for applicants regardless of recommendations received from other state administration (Alien Police, Public Prosecutor’s Office).

Foreign Police reports were as detailed as those requested before the war. They included information about living conditions, citizenship, physical and mental health, and finally yet importantly they informed civil servants about taxes and rent. We were also able to uncover the destinations where people settled after leaving Luxembourg, a further useful source of information for social network analysis.

Confronted with a great amount of data – Conclusion

In recent decades, Jewish refugees have been the subject of many worldwide known studies. They often deal with a micro-historical or prosopographic methodology in pursuit of tracing the migration history of a Jewish community. The various methods address the issues of particular locations, analyze the groups of people involved in the persecutions or study different aspects of the Holocaust. Such small-scale research has also been undertaken in Luxembourg. The incentives often came from outside nourished by debates that make them known in the field of international research activity. The well-known example is the controversy between the historian Christopher Browning and the sociologist Daniel Goldhagen. Having studied the case of members of the German police reserve battalion, two scientists came to opposite conclusions of Luxembourgish soldiers engaged in executions of Jews in Poland. As emerged from Browning’s analysis that 14 Luxembourgers belonged to this unit. Eventually, the argument was closed by the historian Paul Dostert who concluded in the article published a few years later that there was no evidence that one of 14 Luxembourgers had pulled the trigger.

With regard to this conflict, our team must avoid being confronted with some misinterpretations or inaccuracies. It is a very delicate topic and we work with highly sensitive datasets which can be easily misused. It is also important to state that the research is still ongoing and the results may change the perspective and led to new questions and issues in the end, but even now we can come up with some interesting conclusions.

The procedure of repatriation did not change in principle after the war. Applicants had to undergo the same endless ordeal to receive an official permission for staying in their homeland. The whole administration process seems not to have any unified patterns. Though bureaucrats resolved all applications depending on many different variables such as applicant’s property, marital status and the place of living before and during the war. Each civil servant handled the submitted application in a different way. It has appeared that the amount of bureaucracy even increased after the war. In conclusion, our team managed to collect the data that enable to make complex statistics on the pre-war and post-war period. In a few excel sheets we entered the data to pursue the traces of applicants in relation with their family background and fortune. Applicants often had to make a particular deposit to one of the Luxembourgish banks whether they wanted to be successfully approved. Luxembourg administration kept these merciless conditions even after the war and in many cases Jews were obliged to find accommodation in local hotels or private apartments to pay off other Luxembourgers.

Notes

- ID: 15125: Testimony of Lily Friedrich drawn from the database of the USC Shoah Foundation. It exists the full transcription in English and German. ↩

- Fayot was a political historian, specialising in the history of socialism in Luxembourg. He is also a contributor to the daily Tageblatt newspaper on the topics related to socialism. ↩

- CERF, Paul, L’attitude de la population luxembourgeoise à l’égard des juifs pendant l’occupation allemande, in : MOYSE, Laurent et SCHOENTGEN, Marc (éd. par), La présence juive au Luxembourg du Moyen ge au XXe siècle, Luxembourg: B’nai Brith, 2001, p. 71-74, ici p. 72. ↩

- ANLux, MJ-Pet 359472 ↩

- ANLux, MJ-Pet 84893 ↩

Eldad Kisch, MD.

The Dutch did not behave much better.

That, of course, is no excuse for anything.