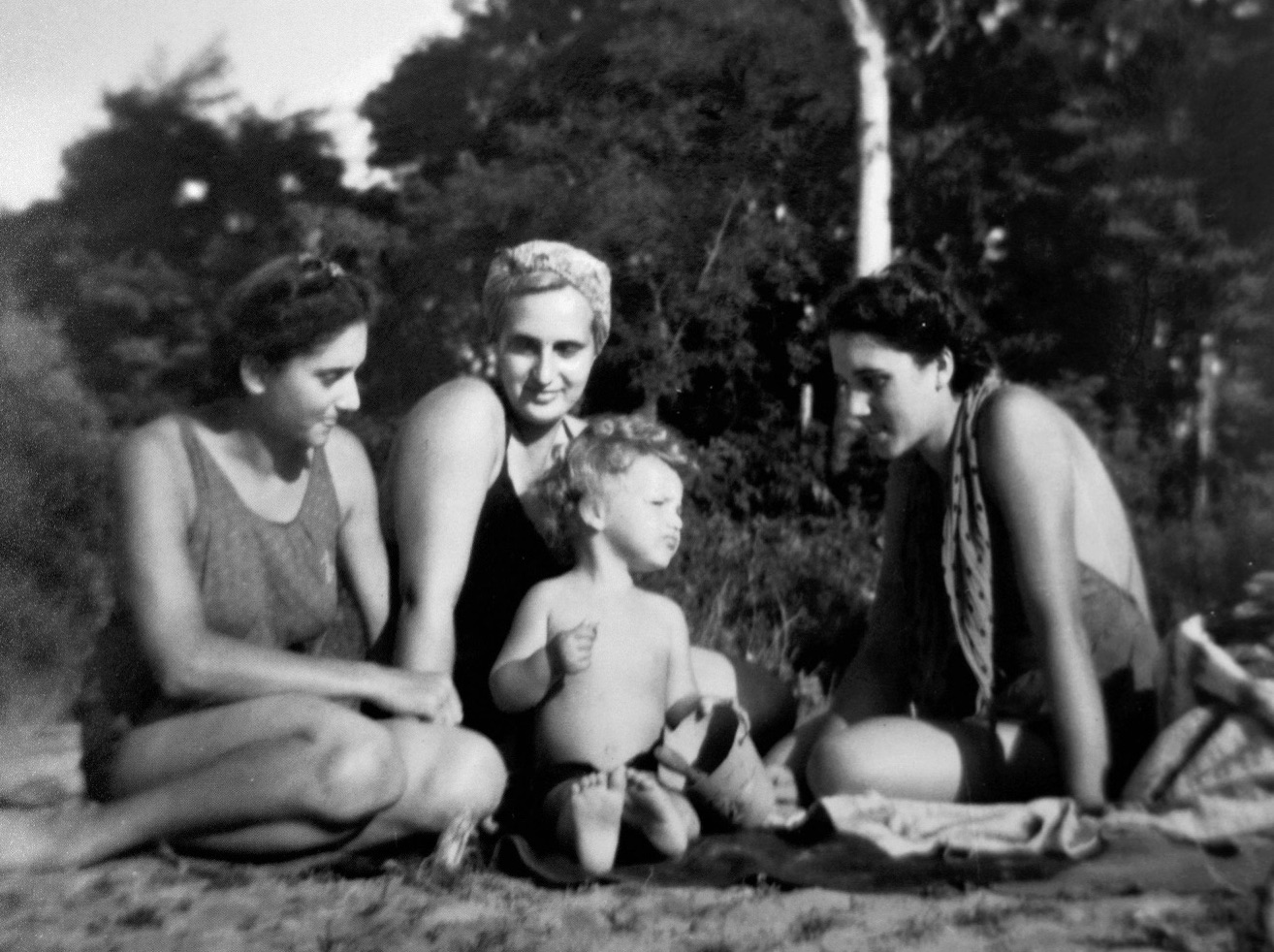

On 9th July 1944, Raoul Wallenberg arrived in Budapest and began work on a rescue project that would protect thousands of Hungarian Jews. His efforts have been the subject of many books, monuments and films, rightly recognizing his heroism. Yet, while his operation has become the main example of rescue in Hungary, many other individuals helped their friends, neighbours, and acquaintances in acts of personal rescue. These people have been largely forgotten in rescue narratives of Hungary; they are Hungary’s ‘anonymous’ resistors. This blog post focuses on some of these ‘anonymous’ resistors; individuals to whom people such as Agnes Balint (neé Schachter) and her young son Gabriel Geza Balint-Kurti owe their lives to.

Dear Sir,

I lived through the second world war in Hungary during the persecution and deportation of my fellow Jews. I was hidden by Christian friends and acquaintances, who all risked their lives so that I and my young son might survive. None of these wonderful people had any ulterior motives for their actions.

Extract from Agnes Balint’s letter to Yad Vashem

In November 2006, Agnes Balint wrote to Yad Vashem nominating three of her rescuers to be recognized as ‘Righteous Among the Nations’. Copies of her letter, personal testimony and nomination documents are held in the collections of the Wiener Library, in London. The question of how to approach personal testimonies – sometimes called ‘ego documents’ – has been the subject of debate among historians. A traditional focus on key figures and institutions meant that the role of ordinary individuals was initially widely ignored. Moreover, some historians viewed these sources as providing nothing more than ‘anecdotal’ evidence, of little use for writing history books. However, rescue operations on a rank-and-file level are not documented by embassies, institutions or officials, but by personal memories. While recognizing the limitations of anecdotal evidence, it is nonetheless important to consider the personal accounts of those who took part in rescue operations. Personal testimonies are a vital spring in the desert of documentation for this part of history. Balint’s files are therefore central to understanding the history behind those engaged in personal rescue operations.

As a private story, Agnes Balint’s account of her rescue from Hungary is deeply personal. Throughout 1944, she relied on friends and friends of friends who supplied her and her young son with their own Christian documents, forged documents, shelter, and support. The story of her rescue is a true social history. While her rescuers were a combination of Christians and Social Democrats, none of them were involved in resistance organisations or had contact with neutral countries’ delegations or international institutions. Their religious and political ideologies no doubt motivated their actions, but they did so on an individual, not an institutional, level. Balint’s rescuers genuinely are ‘anonymous’ rescuers.

He [Jόzsef Strahl] collected the necessary documents, promised to me by Zsόfia Ditrόy, as it was not safe for me to walk around town with a yellow star. He then organized our transport to Ordas. At my request he also accompanied me and my small son on the train, as again I was afraid to travel on my own.

Extract from ‘3rd Rescuer’ Form

A family friend of Agnes Balint, Zsόfia Ditrόy, gave Balint ‘her own documents of Catholic baptism and a letter of Catholic baptism of her son’. This allowed Balint to ‘construct a believable cover story’ so that she and her son could live with a Christian friend, Ödönné Haas (neé Anna Hutter), in the countryside town of Ordas, Pest county. As a Christian, Haas’s actions provide much needed subtlety to our understanding of the role of Christian ideology in the Holocaust. Traditional historical narratives have focused largely on the role of the institutions of the Christian Church, ignoring the actions of individual Christians and assuming that the beliefs of the Church were the beliefs of all Christians. However, Haas had no support from religious institutions. Instead, she took part in rescue as an individual Christian. This highlights the importance of the distinction between the Christian churches as institutions and the Christianity of the common populace, stressed by much of the most recent historiography.

The nature Balint’s nomination documents do, however, limit the extent to which the rescuers’ motivations can be fully understood. As a prescriptive form, they collect information on the rescuers’ actions and motivations as they were perceived by the persons rescued. In this way, they show more about how Balint perceived her rescue than how her rescuers perceived it. Balint’s perception of her rescue is deeply personal, warmly describing her rescuers as ‘wonderful people’ motivated by ‘love, solidarity and friendship’.

The documents contain details about the rescuers’ professional background, but not much on their social background. Apart from their possession of Christian papers, there is no mention of their religious observance. Indeed, Ditrόy, who’s family name was initially Hoffstaedter, changed her name in 1943 to Mesterházi and acquired Christian baptism papers for her and her son, in order to present her family as Christian, rather than Jewish. Although holding Christian papers, it is likely, therefore, that Ditrόy was not highly motivated by Christianity. While this makes it difficult to establish the influences on their personality, it does not imply that Balint’s other rescuers were not motivated by their Christianity, as they did provide her with religious documents. However, due to the complex role of the Church institutions in the Holocaust in Hungary, it is unsurprising that they would not overtly mention their Christian motivations and that Balint chose to omit Christian references from her testimony. Indeed, the role of the Church institutions during the Holocaust became an increasingly political and controversial issue in the immediate post-war years, in which the ruling Communists viewed the Church institutions as ‘obstacles’, the church institutions attempted to deny any support for anti-Semitic policies, and ‘political reasons determined which rescuers could and couldn’t be written about’. Given this and Balint’s interpretation of their motivations as deeply personal, it is clear that when taking part in rescue, Ditrόy and Haas were motivated to help a friend more as an individual than by Christian values.

The risks for Zsόfia Ditrόy and her family were very severe, almost certain death if she had been discovered. As the deportations became increasingly more severe, immediate on-the-spot execution could be the punishment for providing such assistance.

Extract from ‘1st Rescuer’ Form

Balint describes her third rescuer, Jόzsef Strahl, as a ‘Social Democrat [who] was more conscious than others of the dangers of the anti-Jewish regulations’. Indeed, Strahl would have been well aware of the destructive nature of the regime which had arrested many other Social Democrats. Like Ditrόy and Haas, little is known of Strahl’s background, but there is no suggestion that he was part of an institutional rescue operation. Unlike Balint’s other rescuers, however, Strahl was an acquaintance of Ditrόy, not of Balint. His involvement stemmed from a friend asking for help on behalf of another. Yet his participation in rescue is not limited to Balint and her son. He also ‘travelled weekly to the country to take provisions to his ex-boss’, who he was hiding. Furthermore, Balint describes how ‘we were not the only ones [that Strahl was helping] but I don’t know any more details’. This exposes another characteristic of personal rescue operations – secrecy. Unlike partisans who lived in the forest or Jews who lived in protected houses in Budapest, these individuals remained in their own homes. As the anti-Semitic environment intensified following the German occupation and installation of the Arrow Cross regime, families would face ‘almost certain death’ from ‘immediate on-the-spot execution’ if found hiding Jews. It was therefore essential that as few people as possible knew of their actions. After the war, a combination of Soviet suppression, continued anti-Semitism, and a political and academic environment that favored stories of armed resistance over rescue led to stories of everyday rescue being kept quiet. Indeed, rescue stories often took on an ideological and propagandist significance in immediate post-war states, especially in communist eastern Europe. As a result, the exploits of individuals like Strahl, Ditrόy and Haas who – because of their own personal motivations – had the courage to ‘go against the stream’ of anti-Semitism in 1940s Hungary have been largely ignored.

Sir Martin Gilbert once stated that survivors ‘carry in their memories whatever remains of the knowledge of life in more than a dozen countries’. Indeed, the as-yet largely underwritten history of rescue by ordinary people is most effectively seen through the accounts of the rescued. Ideologies and great men – elements that have dominated many of the history books on this topic – are evidently not enough; the actions of ‘anonymous’ resistors like Zsόfia Ditrόy, Ödönné Haas, and Jόzsef Strahl were deeply personal and individual. For them, there is no official paper trail to follow in the archive: there are no protective passes, no official lists. Instead, we have people and their memories. With a window into rescue operations operating across Hungary, not just in Budapest, Balint’s nominations are key sources for further developing a more nuanced understanding of resistance in Hungary. Clearly, we still have much to learn from the testimonies of individuals like Agnes Balint.

Many thanks go to the Wiener Library and Gabriel Balint-Kurti for the use of the photos in this blog post.

Theron P. Snell, Ph.D

An important observation in this time of lumping individuals together in groups, either of the oppressed or oppressors. It also recalls directly the continuum between collaboration and resistance outlined by Werner Rings in his book LIFE WITH THE ENEMY: Collaboration and Resistance in Hitler’s Europe 1939-1945. Finally, it illustrates the limited views of top-down history that ignores how people live within and outside of culture simultaneously.