“I am still so completely under the impression of your terrible suffering that every word that I could thank you with for this [report] seems inadequate….You have thus demonstrated that you have faced up to a moral task, which, as I hope, carries a reward in itself: You have helped to ensure that your experiences are now kept in an archive and preserved for posterity. They have thus received historical meaning beyond the personal.”

Introduction

These lines were written by Dr Eva Reichmann to “ES”1 in a letter dated 10 December 1958.2 Reichmann, then Director of Research at the Wiener Library in London, was referring to a more than 40-page eyewitness account that ES had provided to the Library and which was collected by Reichmann’s colleague, Elisabeth (“Li”) Zadek, in October 1958. The report by ES was submitted as part of the Wiener Library’s ambitious efforts to collect eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust period in the mid-1950s, an initiative that resulted in gathering more than 1,300 written reports in seven different languages. These reports have now formed the basis of a new digital resource being produced by the Wiener Library, Testifying to the Truth, which is currently accessible on site in the Library’s Reading Room and in the near future, will be available online.

Supported by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims against Germany (Claims Conference), the project began in London, from where Reichmann directed a small team of at least four-five paid staff members and additional volunteers to collect reports from survivors. Interviewers were located throughout Europe and worked on tracing, contacting and persuading potential interviewees to take part in the project. Their strategy was somewhat haphazard at first, but in time developed more systematically. The project began in the mid-1950s and continued on until the mid-1960s, proceeding in a concentric and centrifugal direction: they began close to London and gradually spun out further and further as the network of interviewers and interviewees widened.

The reports were not usually drawn up by the survivors themselves, but developed through conversations with the Library’s interviewers. Afterward, the draft report was submitted to the survivor to ensure it was an accurate representation of his or her account, a verification which often resulted in extensive correspondence with Reichmann and her colleagues as well as a signature by the interviewee to confirm that the account had been recorded accurately. However, as far as current ongoing research can conclude, there is no surviving record of the questions or types of questions asked of the survivors nor is there any audio available of the dialogues between survivors and their interlocutors. As Madeline White has rightly noted, the accounts should be considered highly mediated reports drawn up together in most cases by both the interviewer and the interviewee, rather than direct word-for-word “testimony” in the contemporary sense of the word. 3

Although the Wiener Library’s eyewitness reports collection is a written record and interview dialogues have not been preserved, the collection as a whole exhibits similar characteristics and challenges of interpretation to audiovisual Holocaust testimony, which have been identified by Noah Shenker in his study Reframing Holocaust Testimony. Like audiovisual testimony, the Library’s eyewitness reports have also “emerge[d] from an individually and institutionally embedded practice framed by a diverse range of aims…”. Shenker has further noted that testimonies are “molded by institutional and technical interventions at the moment of their recording, [and] they are also shaped as they migrate across various media platforms and as archivists develop new forms of digital preservation.”4 Shenker’s study attempts to find the “institutional voices” inextricably involved in the creation of survivor testimonies, and examines the ways in which institutional priorities and memory politics have been in potential conflict with survivor agency in their production.

ES’s account is a noteworthy example from the Library’s collection to consider the extent to which some of Shenker’s conclusions might apply to written “testimonies”. In its relatively lengthy content, ES’s account demonstrates how the persecution experienced by Jews and others during the Holocaust period caused an irreparable rupture in family life. The account describes her and her family’s harrowing trajectory as a Hungarian Jewish family in Fiume, separated by occupation and deportation, and partially destroyed by genocide. It is also one of the few examples amongst the Library’s accounts in which the survivor’s reflections on the meaning of their experience are recorded.

Because the Wiener Library’s institutional archive contains important contextual correspondence related to the eyewitness testimonies project, including regarding ES’s account, this particular report demonstrates the potential tension between survivor agency and institutional priorities, laying bare some of the layers of mediation involved in the Library’s project. Finally, this short case study raises additional questions about mediation by institutions recording testimonies and the continued use of the reports as digital records, particularly as the Library and other institutions strive to make testimonies more accessible online.

The Account by “ES”: Key Historical Information

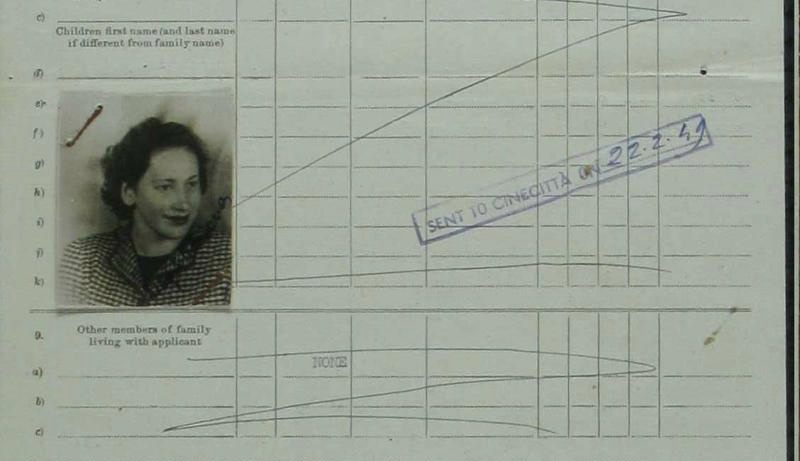

ES’s account follows the format guidelines of the reports in the Wiener Library’s early eyewitness accounts collection.5 Her report, written in German, includes a cover sheet drawn up by Library staff that outlines (in English) the following elements:

- the title of the report: “Kanada”,

- the serial index number given by the Library: P.III.h (Auschwitz) No. 997,

- the length of the report in pages: 41,

- when the report was recorded: October 1958,

- by whom: Miss E Zadek,

- and when it entered the collection: March 1959.

The cover sheet also includes the contours of ES’s path of persecution and references keywords identified by Library staff for purposes of cross reference. These reflect institutional interests and include personal names (of both helpers and collaborators), geographic locations, camp and ghetto names, groups of people, nationalities and other terms. There is also a “further reference” section that points the researcher to sections within the report of potential particular interest (here “Non-Jews Helping Jews”, “Dr Mengele”, the first names of the Blockaelteste and her sister, and an Italian collaborator and helper named “Silvano Guerrini.”

Within its 41-pages, the account details the movements of the family, which included ES and her husband, who had become blind, her two daughters, MS and AS, and ES’s parents, from their home in the contested city of Fiume (Rijeka in Croatian). Despite living under Fascist rule in Fiume, ES emphasized in her report that she and her family did not experience antisemitism in Italy until September 1943 when Nazi Germany occupied the area. With this harsh reality, the family left for Venice, then Florence, and then Prato, trying to escape the roundups.

The family became separated and ES, her parents and husband, went to Sesto Fiorentino, where they found temporary reprieve in hiding, until the Mother Superior of a local Catholic parish denounced them. Her daughters and mother remained behind in the area of Florence. ES, her husband and father were arrested and sent to Fossoli, then were transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Here she was separated from her husband and father and saw them for the last time. ES was selected for forced labour in the so-called Kanada commando, sorting clothing, goods, food, and other belongings that were brought into the camp by deportees.

In time ES was transferred to Zschopau near Chemnitz, where she was forced to work for the Deutsche Kraftwerk Union, after which time she was sent on an evacuation transport by train, “the eight most horrible days of [her] deportation,” to the Theresienstadt ghetto. After five to six weeks in Theresienstadt, she was liberated and was sent first to Prague for recuperation, and then to camps for displaced persons in Kaisersteinbrueck near Vienna and Marburg. She returned to Fiume, where she learned that her two daughters and mother had survived in Florence and were searching for her. The three generations of women were reunited after the war.

See fullscreen visualisation of “Map of family’s path of persecution:”

Mapping the family’s trajectory of persecution was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

ES’s account is vivid and harrowing, particularly of her work in the Kanada commando, with its graphic depictions of the fraught negotiations between different national groups of prisoners as well as descriptions of sexual relations amongst prisoners, many of whom bartered for food and sought means to survive camp conditions by supplementing their meager diets. ES also made a compelling observation about the name “Kanada” – the origins for which have not been fully clarified in the literature on Auschwitz. She notes: “The question remains why it was called ‘Kanada’. I think its original name had been ‘Kanaan’ – the land of milk and honey – and had then been renamed by the SS who were not well versed in the Bible into ‘Kanada’.” Like other Wiener Library accounts (which suggests that this focus was potentially a common question asked of interviewees), she described some instances of help, including from an SS guard. She examined national divisions among Jewish internees, including after her transfer to Zschopau.

Her report ends with a poignant reflection on her own personal agency in explaining the reason for her survival, which is a somewhat uncommon inclusion in the Library’s testimonies collection. In a separate, final section titled “Why I Survived – How I See It”, she has concluded that her desire to remain alive, her persistent feeling of responsibility for her daughters and mother (the latter she assumes expected the return of her able-bodied daughter but not her elderly husband or blind son-in-law), and her practical experience and attempt to remain as physically clean as possible through her deportation all contributed to her survival. She noted defiantly that once the racial laws were introduced in Italy, a non-Jewish woman had proclaimed that “All the Jews will have to die” to which she had responded, “I’ll be damned if I will!”.

Survivor Agency and Institutional Priorities

Perhaps as equally compelling as the historical content of the report itself, the creation of the report and its acquisition for the Library attest further to ES’s perception of her own agency as she attempted to maintain a certain amount of control over the afterlife of the narrative she had compiled with Li Zadek (although, again, there is no documentation about the dialogue between the two – only some outlines, as suggested below). As correspondence with Library staff demonstrates, ES’s conception of her own role in authoring the account and controlling its content did not always go hand in hand with institutional priorities, which focused primarily on gathering material to advance research. Handwritten notations on the copy of the 1958 report as well as correspondence with ES stored in the Wiener Library’s institutional archive reveal the multiple layers of mediation involved in the production of this report, a process that further research will likely reveal is applicable to others.

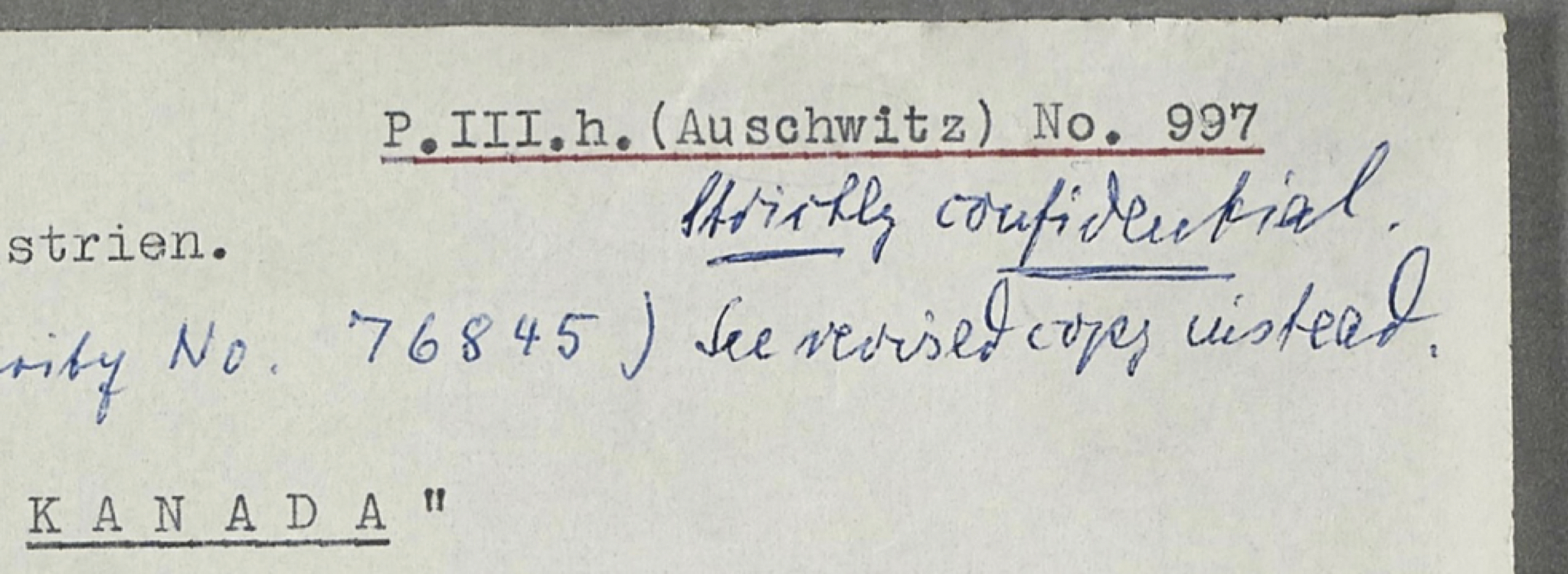

The notations on the report dated October 1958 include corrections to a few grammar mistakes in German, additional clarifying addenda, including for example the notation of ES’s assigned inmate number in Auschwitz, as well as a handwritten note on the cover page that the report is to be kept “strictly confidential: see revised copy instead.” It is presumably this version of the report to which ES referred in replying to Eva Reichmann’s aforementioned letter of 10 December 1958 with a letter of her own a few years later.

ES begins her letter dated 5 February 1962 with a pointed remark that she believes Reichmann “will be surprised” to read this letter – perhaps because several years had passed since she had submitted the report, but also likely because of the nature of her request. In having had multiple conversations with acquaintances who had asked about her experiences during the Holocaust, she set out to rework and revise the account she had submitted to the Library because she noticed several “flaws” in the version that had been sent, despite having worked with Li Zadek to correct and revise them. She was displeased by the lack of attention on the part of her interlocutor, but recommended that Reichmann be discreet in her discussions about these shortcomings with Zadek, since Zadek had been helping her with other personal matters at the time.

ES emphasized the need for revision because “when I told my story to Miss Zadek, the only things that gushed out of my mouth were what I had gone through and what I had been suffering from, which I had been suffering for years in silence.”6 ES further requested the return of the original report, including any copies that had been sent to Yad Vashem (at this time, the Library worked in cooperation with Yad Vashem, which funneled the funds from the Claims Conference to the Library for the production and indexing of the reports in return for copies of the reports for Yad Vashem’s collection). After the Library returned her original account to her, ES explained, she would in turn re-send the revised version.

By the time E’s letter reached the Library, however, Eva Reichmann was no longer in post as Director of Research. A letter dated 6 March 1962 from C.C. Aronsfeld, then Acting Director of the Library, confirms the delayed receipt of her letter, and indicates that the process of retraction was not as straightforward as ES had hoped. Aronsfeld noted that there was one copy at the Library and two at Yad Vashem, to which she would have to write directly for those copies. Aronsfeld reassured ES that her report would be excluded from any publication and attempted to convince her that the original report should be kept for internal purposes in the archive, since it contained information that was excluded from the second version she had submitted. (Presumably ES had sent the edited version to the Library by this time.) Aronsfeld also noted that the revised version does not contain her signature, which was problematic for the Library.

ES replied from Bern immediately on 12 March 1962, noting her “surprise” and “disappointment” with the Library’s position, although she admitted that she forgot to sign the revised version. She conceded that in addition to allowing some personal aspects of the testimony that she had wished were not included in the record to remain, she also added important information that she felt Miss Zadek had omitted from the original submission. She requested a copy of the second version to be returned so she could indeed re-submit it with her signature.

The final recorded correspondence between ES and staff of the Library is a somewhat terse reply from Aronsfeld on 19 March 1962, indicating that he had enclosed the original manuscript as well as the second version, which ES should sign and return to the Library. The correspondence record is closed at this point.

Further Mediation and the Ethics of Access

As noted above, the Wiener Library’s collection of early eyewitness accounts gathered by Reichmann and her team, including the report by ES, have formed a body of material that serves as the basis for a new digital resource for researchers, Testifying to the Truth, currently only accessible in part from the Library’s premises in London. The creation of this resource dovetails with the Library’s recent efforts to overhaul its digital processes and its priority to make more of its collections accessible to researchers outside of London.

Thus many of the reports have been translated into English, digitized, fully catalogued and digitally preserved. The Library intends to publish the collection online to make it accessible to researchers, although a number of issues related to privacy and intellectual property are currently being investigated and considered carefully before proceeding. In the process of developing the new digital version, the Library has conducted a crowd-sourced effort to identify those who were interviewed or their descendants, and other research has been conducted and is ongoing to ensure compliance with data protection and copyright regulations as well as ethical considerations. These efforts are being fully documented, and where possible, may in future form part of the documentary record of the creation of this “new” archive.7 As Shenker and other authors have suggested, this kind of information is vital for understanding the ways in which “institutional voices” help create testimony collections, and therefore, inform our interpretation of these testimonies. Rather than relegating “moments that capture of a sense of the dialogical, mutual labor involved in testimony” to the periphery of the archival process, Shenker has noted, this mediation should be recognized through the development of a “testimonial literacy”.8

To return to the challenges of reading ES’s report in particular: The Library appears to retain an original copy of the edited version by ES, in which she added information by hand that she emphasized Li Zadek had omitted. However, it is unsigned so it is possible that the signed version was never returned (or retained). As noted above, ES indicated that her report was “strictly confidential” and the revised version should be used instead, but this is the only copy that is found in the Library’s collection, including the parts that have been crossed out, explained or underlined – presumably by her own hand. This version has been digitized and translated, but because it has been marked confidential, as is the case with some dozen other accounts, access to the report is restricted. Accordingly, I have anonymized my own references to the report, in hopes of upholding the author’s wish for privacy, but also recognize the “shared labor” (in the words of Bolkosky and Greenspan9) that likely produced the significant historical content in the report and which is in part visualized on the map above – that to which Reichmann undoubtedly referred in her remarks regarding “historical meaning beyond the personal”. Interestingly, the correspondence with ES regarding the “afterlife” of her narrative in fact returns the discussion back to the “personal” – the elements she wanted to have removed, she felt, reflected problematic personal opinions she held at the time of being interviewed.

“You have helped to ensure that your experiences are now kept in an archive and preserved for posterity. They have thus received historical meaning beyond the personal.”

Dr Eva Reichmann to “ES”, 1958

Finally, the case of ES is an illustrative example supporting how testimonies might be read and interpreted with a consideration of the institutional priorities at the time they were collected as well as when they are further digitized and disseminated, as Shenker has ably shown. That a cover sheet including indexing, keyword references and a numerical sequence was drawn up for ES’s report suggests that the Library’s aim to collect “for posterity” recollections of survivors may have outweighed ES’s intentions in providing the report – it was, after all, acquistioned and indexed within the collection. That Aronsfeld emphasized the need to retain information that ES herself wished to be omitted further signals the priorities of the time.

Likewise, the Library’s current priorities continue to shape its decision to digitize, further mediate, and make accessible reports like ES’s for greater research access while attempting to balance this with individuals’ requests for confidentiality and privacy.10 The exploration of this account as a case study for gaining further understanding of the history of this collection raises additional questions: How do we make personal information in testimonies and eyewitness accounts available for research, education and commemoration while respecting the wishes and intentions of survivors (or more generally, donors of personal material to archives)? How can archives make their own “institutional voices”, priorities and role in the creation of collections more accessible and central in the archival record for researchers as they interpret different testimony collections? And what happens to the possibility for close reading and “reading against the grain” (in the words of Jeffrey Shandler)11 of a testimony when they are taken “out of context” or orphaned from the original collection to which they were acquisitioned or if they are detached from related collections (in this case, the Library’s institutional archive)?

With thanks to Wolfgang Schellenbacher for his assistance with the data visualization, to Ben Barkow for a review of the draft, and to Leah Sidebotham and Toby Simpson.

Notes

- The author of the eyewitness report in this case study has been anonymized according to her wishes for confidentiality, which is in part a topic of discussion in this blog post. ↩

- Wiener Library, Wiener Library Archive, Correspondence with ES, 3000/9/1/1370. ↩

- Royal Holloway, University of London doctoral candidate Madeline White grapples with the definition of testimony and its application to the Wiener Library eyewitness accounts in her thesis, which was presented as “Contextualising Oral History Methodology: A Case Study of the Wiener Library Holocaust Testimony Collections,” Research Workshop: Holocaust Testimony, Royal Holloway, University of London and Wiener Library, 7 December 2018. For a further discussion of the limits of the term “testimony” in describing dialogues between “interviewer” and “interviewee”, see Henry Greenspan and Sidney Bolkosky, “When is an interview an interview? Notes from Listening to Holocaust Survivors,” Poetics Today 27, no. 2 (summer 2006): 431-449. ↩

- Noah Shenker, Reframing Holocaust Testimony (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), 1-2. ↩

- Wiener Library, P.III.h (Auschwitz) No. 997. ↩

- Wiener Library, Wiener Library Archive, Correspondence with ES, 3000/9/1/1370. ↩

- With thanks to Toby Simpson, former Head of Digital (now Head of Development) for the Library , and Leah Sidebotham, Digital Asset Manager at the Library, for their helpful discussion of these issues. ↩

- Shenker, 151. ↩

- Greenspan and Bolkosky, 439. ↩

- Sara S. Hodson, “Archives on the Web: Unlocking Collections while Safeguarding Privacy,” First Monday 11, no. 8 (August 2006). https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1389/1307 (accessed 13 April 2019). With thanks to Leah Sidebotham for this reference. ↩

- Jeffrey Shandler, “Holocaust Survivors on Schindler’s List; or, Reading a Digital Archive against the Grain,” American Literature 85, no 4 (2013). See also, Shandler, Holocaust Memory in the Digital Age (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017). ↩