Part II: The Profile of the Perpetrators

Introduction

Part I of the present blog post provided the readers with an overview of one of the last and bloodiest crimes committed by Hungarian extremist Arrow Cross militiamen in Budapest at the very end of the war. The documents presented included post-war testimonies of eyewitnesses and survivors, wartime reports and documents of post-war autopsies and exhumations, culled primarily from the Records of the Committee for the Investigation of Nazi and Arrow Cross Atrocities and two other collections. See:

Murdered on the Verge of Survival: Massacres in the Last Days of the Siege of Budapest, 1945

Part II of the blog post focuses on the personality, social background and motivations of the members of the killing squad, and on the inner power structure of and responsibilities within the Arrow Cross Party. It features unique Arrow Cross Party records acquired by the Hungarian National Archives in the last two decades, including registration files and membership cards previously held by the Hungarian state security organs, and the Arrow Cross administrative and private records captured by the US Army. In addition, the blog also cites a document from one of the early war crimes trials.

See fullscreen visualisation of Massacres in the Last Days of the Siege of Budapest, 1945

Mapping the documents was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

Please follow the links for metadata, scans, transcripts and translations of the documents:

- Registration files and card index of Arrow Cross Party members, 1939-1944 (Hungarian National Archives)

- Pocket address book of head of the Arrow Cross State Building Office Vilmos Kőfaragó Gyelnik, 1944-1945 (Hungarian National Archives)

- A speech attributed to “Father” András Kun (Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security)

Please follow the links for the collection descriptions in the EHRI portal:

- Records of the Arrow Cross Party, 1932–1945 In Hungarian National Archives (MNL OL) P 1351

- Collection of (Hungarian) Political and Military Records In Hungarian National Archives (MNL OL) K 814 (copies: NARA RG242/1053, USHMM RG-30.003M, MNL OL X 7076)

- People’s Courts investigative and trial records of András Kun In Records of State Security Investigations of Hungarian War Criminals Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security (ÁBTL), (copy: USHMM RG-39.018M)

Historical background

From the early 1930s on, various national socialist parties emerged in Hungary. Some of them were mere copies of their Nazi German counterpart, whereas others were, to quote Columbia University History Professor István Deák, “genuinely domestic products”. The most popular of these formations became the Arrow Cross Party (Nyilaskeresztes Párt), founded by former officer of the General Staff, Ferenc Szálasi, in 1935, under the name “Party of National Will”. Szálasi was an extreme nationalist and a fanatical antisemite, but it was his radical anticapitalist views and his promises of large-scale land reform that was met with opposition in establishment circles. Successive conservative governments made excessive efforts to suppress the Arrow Cross. Szálasi was imprisoned and his party dissolved several times between 1938 and 1940. This had the unintended consequence of elevating Szálasi to the status of martyr in the eyes of his supporters. He re-entered political life with renewed popularity. In the last pre-war elections, in 1939, the Arrow Cross gained 29 seats, making it the second largest party in parliament. In fact, the popularity of the party was even higher than the share of its parliamentary representation, but the government blocked several Arrow Cross candidates from running in the elections by administering targeted administrative measures against them. After merging with other far-right organizations, the party was re-named the “Arrow Cross Party-Hungarist Movement”, in 1942. From this time on, the popularity and power of the party was slowly diminishing, mostly because they could not cope with the great expectations of many supporters.

Despite ideological similarities, the relationship of the German Nazis and the Arrow Cross was quite uneasy. Germans deemed Szálasi politically unreliable and unmanageable, and rejected his views on Hungarian regional hegemony. Therefore, they supported other far-right parties in Hungary. This explains why the Arrow Cross was left out of the pro-Nazi coalition cabinet composed after the German occupation in late March, 1944. However, by the end of 1944, the Arrow Cross had become the only potent political force in Hungary ready to support the German cause. After Regent Miklós Horthy’s poorly implemented attempt to extricate Hungary from the war on October 15, 1944, the Arrow Cross Party assumed power with Nazi support. From October 16, 1944, until March 28, 1945, Ferenc Szálasi was prime minister of Hungary as well as its plenipotentiary head of state, bearing the title “Leader of the Nation” (nemzetvezető). Following the war, Szálasi and several other Arrow Cross leaders were sentenced to death and executed.

By the time of the Arrow Cross takeover, the some 150,000 Jews living in Budapest had been forcibly relocated into so-called “yellow star houses“. Due to Romania’s switching sides to the Allies on August 23, 1944, their deportation was tabled and it seemed that the largest surviving Jewish community in Hitler’s Europe could stay alive until the end of the war. On October 15th, however, their lives were in danger once again. Right after the takeover, hastily armed Arrow Cross militias started to terrorize and kill Jews in the streets of Budapest. However, a couple of days later, the Arrow Cross government halted arbitrary violence, as their foremost interest was to stabilize order and consolidate their rule. Despite his militant antisemitism, Szálasi – to the Germans’ surprise – was much less willing to cooperate with them on the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”, and instead he forged his own path. Szálasi envisioned his future “empire” without Jews and intended to nationalize their wealth. He regarded Jews as an expendable workforce in the war effort, but did not intend to exterminate them. Therefore, he refused German demands for deportations, and created ghettos in Budapest to concentrate its Jewish inhabitants. At the beginning of December, before the Soviet blockade closed around Budapest, the Arrow Cross leadership fled to Western Hungary and would later continue its flight to the Reich. In such a power-vacuum, lower level party leaders and (often self-appointed) commanders of party militias took over. Terror was unleashed yet again in the streets of Budapest. Members of the Armed Party Service (fegyveres pártszolgálat) and Armed National Service (fegyveres nemzetszolgálat) committed atrocities without orders or even the consent of their superiors. As described in detail in Part I of the blog post, members of the Arrow Cross Party militias in District XII of Budapest waged a particularly cruel private “war” against the Jews and the opponents of their rule and ideology.

The Diversity of the Arrow Cross Records

Most of the records of the Arrow Cross movement and the 1944 Arrow Cross administration disappeared or were deliberately destroyed at the end of the war. The surviving records form a particularly diverse cohort of files. A large part of material evacuated to the west in 1945 was captured by US Army troops in Germany and subsequently taken to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington DC. The United States returned the collection to Hungary in 1998. The records that remained in Hungary were in the possession of the Communist-dominated police after the war. Certain files were handed over to the National Archives during the 1960s, but the part considered classified, including the personal files (card index) of Arrow Cross Party members remained in the possession of the state security organs. Following the transition of 1989-90, the files were transferred to the Institute of History, the predecessor of the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security. In 2006, the collection was taken to the Hungarian National Archives. The collection contains the personal files of party members arranged into a card index (Boxes 4-56) in alphabetical order from the years 1939–1945. Another key group of records is the records of war crimes trials against the members of the Arrow Cross government, ideologues and militiamen between 1945 and 1967, held in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security, as well as in the Hungarian National Archives and the Budapest Municipal Archives.

The Arrow Cross: Alibi of the Nation

Their bloody reign notwithstanding, the Arrow Cross was responsible for less than ten percent of the victims of the Holocaust in Hungary. When the party came to power, most of the Jews from the areas outside of the capital had already been murdered. Due to the smooth and, at times, willing participation of the Hungarian civil service and law enforcement, between May and July, 1944, close to 450,000 people were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and gassed on arrival. Despite these facts, right after the end of the war, the Arrow Cross served as the “alibi of the nation”. Instead of facing the complex problem of broad societal collaboration, it seemed feasible for the new political powers to put all the blame on the “lunatic” Szálasi and his extremist party. The name of the body established to collect evidence of these crimes right after the siege of Budapest, the Committee for the Investigation of Nazi and Arrow Cross Atrocities, is quite telling: it implies that all war crimes were committed by a handful of collaborators and the Nazi invaders. The press and organs of propaganda often demonized Arrow Cross defendants: in this way, there was no need to admit complicity and analyse the deeply-seated antisemitism and xenophobia that had permeated the society at large.

These views lived on in historical publications and popular remembrance up until present day. Arrow Cross perpetrators were described as originating from the working class, or from other déclassé segments of society (the so-called “Lumpenproletariat“ in Marxist terminology), including quite a few hoodlums and common criminals, as well as uneducated people who had been misguided by propaganda, including teenagers. The analysis of the personal files of Arrow Cross Party members held in the Hungarian National Archives, however, provide us with a more nuanced and somewhat different picture. The Arrow Cross Party organisation in District XII consisted of more than one thousand members in the peak years. The core group which actively participated in the raids and/or the looting in 1944 is estimated at 40-50 persons. This group mostly included old party members from the neighbourhood. Only in the last weeks of the siege were they joined by a few new figures from other parts of the city which had already been taken by the Soviets. Most of the members of the killing squad joined the party before the outbreak of the war, and they had known each other for years. The core of the group consisted of family men in their thirties and forties, serving as the district leader, group leader, deputy section foreman, block leader, and other functions in the party organisation, who encouraged (or forced) their family and friends to join the party. The new members and the younger members were actually almost exclusively family members and neighbours. As it can be seen on the map presented above, they lived near the yellow star houses and Jewish institutions that became their main targets.

The majority were workers, craftsmen and blue-collar employees of industrial and trade businesses, including, for example, a hairdresser, a shoemaker, a baker, a painter, a janitor, a mechanic, and an electrician. However, at least a third of them belonged to the urban lower middle class, and had higher social status, including clerks and state employees, mostly from the transportation company. Three leading figures had their own trade businesses. All but one of the adult party group members completed at least six classes of elementary school and about 40 percent of them had secondary education as well. None of the group members had had a criminal record before 1944. Nevertheless, intoxicated by the unexpected level of power that fell upon them, these foot soldiers of the Arrow Cross movement quickly turned towards extreme violence. They were motivated by social frustration, and a desire to avenge alleged wrongdoing on behalf of the Jews, fear of the Soviet invasion, as well as sheer greed. The situation provided them with an unexpected opportunity for social mobility. They accepted the anti-Jewish campaign not only as legal, but also as legitimate: the recovery of what had been “taken” from them: jobs, positions, and wealth. All of them had a good share of the looted assets and some families moved into seized Jewish apartments. As a result of the “cumulative barbarization” in the bedlam of the siege, many of them followed their darkest instincts and descended into habitually committing acts of brutal torture, humiliation, and rape.

The events that unfolded in Budapest in the winter of 1944/45 seem to support the “ordinary men” theory: common people, average law-abiding citizens, are inclined to commit atrocities in extreme historical circumstances, under peer pressure or simply by following orders.

Among the members of this Arrow Cross group, the only one with higher education was the rogue Catholic monk “Father” András Kun. He joined the Arrow Cross party at the late date of the spring of 1944 and rose quickly within the party hierarchy. His former superiors accepted him as a charismatic leader. He was the one who provided the militia members with the ideological legitimization and further incited their hatred with antisemitic tirades. The speech of András Kun published in this blog was preserved in the material of the post-war trial against him. It is far from being an original piece, using popular metaphors of Nazi propaganda, depicting Jews as spiders who capture and exploit Gentiles in their cowardly, cunning ways. Due to this indoctrination, militia members believed that participation in the raids was a patriotic act and committed their crimes without any remorse.

Vince Kasza, depicted above, represents a “typical” militiaman from District XII. Born in a poor village in Eastern Hungary in 1898, he moved to Budapest after WWI, where he served as a building manager and as a waiter during the war years. Having joined the party in its heyday in May 1939, he emerged to district leader in 1941 and group leader in 1944.

Aside from housewives driven to the movement by their husbands, there were quite a few fully-devoted female volunteers, who often actively participated in collective violence. In the Arrow Cross group of District XII these included Erzsébet Dési Dregán, née Huszár, the head of the women’s group and Erzsébet Jankovics, née Szabó, a nurse serving in the Maros street Jewish hospital who reported her own patients to the murderers (depicted on the photo published in Part I of the blog).

As mentioned before, top party leaders and intellectuals were not directly involved in the atrocities. During the post-war retributions, the authorities tried to put the blame on newly-recruited members of the party militias and on the Germans. These groups certainly did bear responsibility for war crimes. Personal records of the leading Arrow Cross ideologue, Professor Vilmos Kőfaragó-Gyelnik (1906-1945), for example, prove the connections between party elites and the killing squads. Kőfaragó-Gyelnik, an internationally renowned botanist, the leader of Arrow Cross State Building Office, was the one who employed András Kun in the party headquarters of Pasaréti Road 10, and involved him in propaganda work. At the end of November 1944, Kőfaragó-Gyelnik left the city. He died in Austria in March 1945 during air attack. Kun’s address, penned by Kőfaragó-Gyelnik, in his pocket address book became obsolete after the takeover, because Kun moved into a seized Jewish apartment in the Városmajor area, just blocks away from future murder sites.

For an Arrow Cross propaganda film depicting the takeover and the armament of Arrow Cross militias, featuring András Kun and his accomplices, see: “Hungarist Newsreels”, October 1944 http://filmhiradokonline.hu/watch.php?id=5883 (from 2:28)

Bibliography

On the Arrow Cross and its ideology in general, see: Deák, István, The Peculiarities of Hungarian Fascism. In Randolph L. Braham, and Bela Vago, eds. The Holocaust in Hungary: Forty Years Later. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985, 43-51.

On the ghettoization in Budapest in 1944, see: Tim Cole, Holocaust City. The Making of a Jewish Ghetto. London: Routledge, 2003, Chapters 5-8.

For a detailed account on the siege of Budapest and an overview on the Arrow Cross terror in general, see: Krisztián Ungváry, The Battle for Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II. London-NY: I.B. Tauris, 2010, esp. pp. 236-251.

For a documentary account and overview on the Arrow Cross rule, mass murders, and international rescue, see: Zoltán Vági, László Csősz and Gábor Kádár, The Holocaust in Hungary. Evolution of a Genocide. USHMM-AltaMira, 2013, Chapters 5 and 9.

For an analysis on Arrow Cross women, see: Andrea Pető, Gendered Exclusions and Inclusions in Hungary’s Right-Radical Arrow Cross Party (1939-1945): A Case Study of Three Female Party Members. Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLI, Nos. 1-2 (2014)

***

Translation of the documents: Gergő Paukovics, Hungarian National Archives

Special thanks go to Wolfgang Schellenbacher (Jewish Museum in Prague) and Krisztina Oláh (National Széchényi Library Map Collection) for their invaluable contribution to the editing process. We are grateful to our colleagues at HNA and partner institutions, Mihály Soós and István Orgoványi (Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security), Anton Avar (Hungarian National Archives), Zsuzsa Toronyi and her team (Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives), Tamás Lózsy (Hungarian Orthodox Jewish Archives) and Borbála Kriza (ELTE University), who provided vital assistance in obtaining the documents and photos featured in this blog post.

© Map of Budapest, 1937-38, courtesy of National Széchényi Library, Map Collection TA 6 696/ 25-27, 31-33.

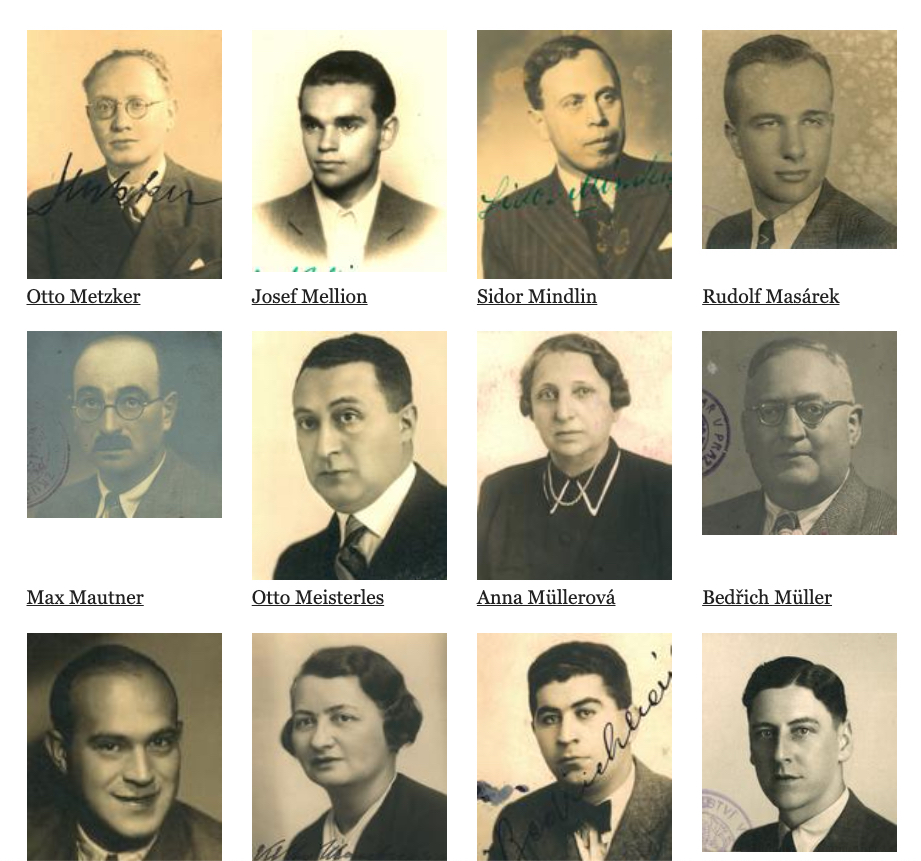

© Photos: courtesy of Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives and Hungarian Orthodox Jewish Archives

***

Laszlo Csosz

A new documentary on the aftermath, memory and legacy of the massacres:

https://444.hu/2021/01/31/monument-to-the-murderers

(English subtitles are available at Settings)